Where the Game is Headed

LONDON — The date is October 26, 2025, and we’re six minutes into the second quarter of an NFL game at Wembley Stadium. This isn’t just another contest in an international series, either. The league has finally put a team across the pond, the Monarchs. And running the ball, if you’re wondering, is still part of the game.

The Washington Red-White-and-Blueskins have a 1st-and-10 at the Monarchs’ 40-yard line. Both sides are set before the snap, but football looks different than it used to. Offensive linemen are squatting at the line of scrimmage, the three-point stance having been outlawed; the constant clashing of the helmets in the trenches is no longer part of the game, to reduce the number of subconcussive hits. Washington’s running back takes the handoff, plowing forward with his head down as the Monarchs’ All-Pro outside linebacker, No. 97, comes on a blitz.

The ensuing helmet-to-helmet hit is now illegal, even though it occurred inside the tackle box and behind the line of scrimmage. Back stateside a few days later, the tailback will receive the dreaded electronic notification from the NFL that he’s been fined for leading with the crown of his helmet. Like all helmet-to-helmet fines, the money will go directly to studying brain injuries through the Sports and Health Research Program at the National Institutes of Health.

Here at Wembley, No. 97 heads to the sideline. The paper-thin accelerometers embedded in his helmet have just recorded an impact of 130G on the upper left side of his head, and the data is sent to a pager-like device on the hip of the team’s athletic trainer. Was No. 97 concussed? Rather than trying to gauge his cognitive awareness through a series of memory tests as in the past, the trainers will prick No. 97’s finger with a small needle—like a diabetic checking his blood sugar—and in less than a minute they’ll know whether he has an elevated level of a protein that gets released into the blood after a brain injury.

Can football change? Will the sport become safer? How are concussions impacting the game’s future? Introducing an in-depth series where we tackle those questions, starting at high schools and continuing into college and the NFL. Read the entire series.

In this instance, No. 97 was concussed.

In the locker room, he slips on a black virtual reality mask and, for the next 15 minutes his neurocognitive function is measured as he navigates a simulated playing environment. His test results are uploaded into an expanded form of the electronic medical records the NFL began using in 2013, and are easily accessible on a tablet by the team’s physician. Just as he carries his U.S. passport in Britain, so too does No. 97 carry his “neurological passport.”

The passport’s stamps are his baseline test results; his concussion history; a tally of the magnitude, location and frequency of impacts he’s sustained in practice and games, as measured by helmet sensors; the results of blood tests like the one he took on the sideline; images produced from brain scans like the one he’ll have the next morning; and his genotype (ApoE e3,e3) of a gene linked to how well a person recovers from brain injury.

An algorithm processes all this information and provides a result that will answer a question at the center of football’s present-day concussion crisis: What is the risk of No. 97 continuing to play the game?

* * *

Is any of this hypothetical scenario possible? The answer is yes, and it may happen sooner than you think.

For a week, The MMQB has explored football’s identity crisis as it tries to reconcile its inherently violent nature with the need for a safer game. While the past decade brought the issue of head injuries in football to the forefront—dozens of cases of chronic traumatic encephalopathy found in the brains of deceased gridiron stars; a concussion lawsuit that the NFL settled with former players; and President Barack Obama saying he’s unsure he’d let a son play football—the sport is now at a crossroads.

Will it fizzle and fade away? Or will it adapt and continue to grow?

In the future, team medical personnel will have a range of diagnostic tools on the sideline and in the locker to evaluate the extent of a player’s head injury after a hit. (Bob Levey/Getty Images)

The next decade will bring more answers. Each of the measures described in our look-ahead to 2025—the rules changes, the diagnostic tests, the neurological passport—have been either proposed, considered, brainstormed or researched (except for Washington’s name change, or so we think). But there is still a gap to be bridged by science and research, which takes place on a very different timetable (years) than that on which the game of football is played (days).

Concussions are distinct from other injury players sustain, and the immediate goal of team medical personnel is to diagnose and manage them based on objective data. The NFL currently uses a sideline concussion assessment that includes a symptom checklist, verbal tests of word recall and concentration, and a balance test (consistent with the 2013 Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport). The team physician is responsible for the player’s diagnosis but has help from an athletic trainer in the press box (the “eye in the sky”), an unaffiliated neurotrauma consultant and video replays accessible on the sideline to only the medical team. There is a standardized return-to-play progression in the NFL, and discussions have started to include a more specific return-to-exercise portion, too, with details such as the heart rate that should not be exceeded in certain stages.

A simple pin-prick on the sideline may be able to reveal the presence of proteins released into the bloodstream when the brain suffers a traumatic hit. (Monique Heydenrych/Getty Images)

How will this process improve? One way is the search for a biomarker—a particular substance that could be detected in blood, saliva or urine, and that would signal that head trauma had occurred. For example, last spring a group of researchers at the University of Rochester and the Cleveland Clinic published research that showed elevated concentrations of a certain protein in the blood correlated with more hits to the head among a group of college football players.

This protein, S100B, is mainly present in the brain and spinal fluid, so increased levels in the blood show that the barrier separating the brain and the bloodstream has been opened by some kind of head trauma. At the moment a blood test for levels of this protein is best used for ruling out concussion rather than diagnosing it, and takes about an hour to yield results in an emergency room. It’s not yet a rapid yes/no sideline concussion test, but such a test might not be far off.

Changes in the brain can be quantified with the help of technology, even something as simple as a virtual reality system or an app developed by Cleveland Clinic that uses a tablet’s built-in accelerometer and gyroscope. These tests register a longer return to baseline than other widespread assessment tests like the imPACT or SCAT2. By 2025 we might see the accepted timeframe to return from a concussion increasing from a seven- to 10-day window to a few weeks, on par with a high ankle sprain.

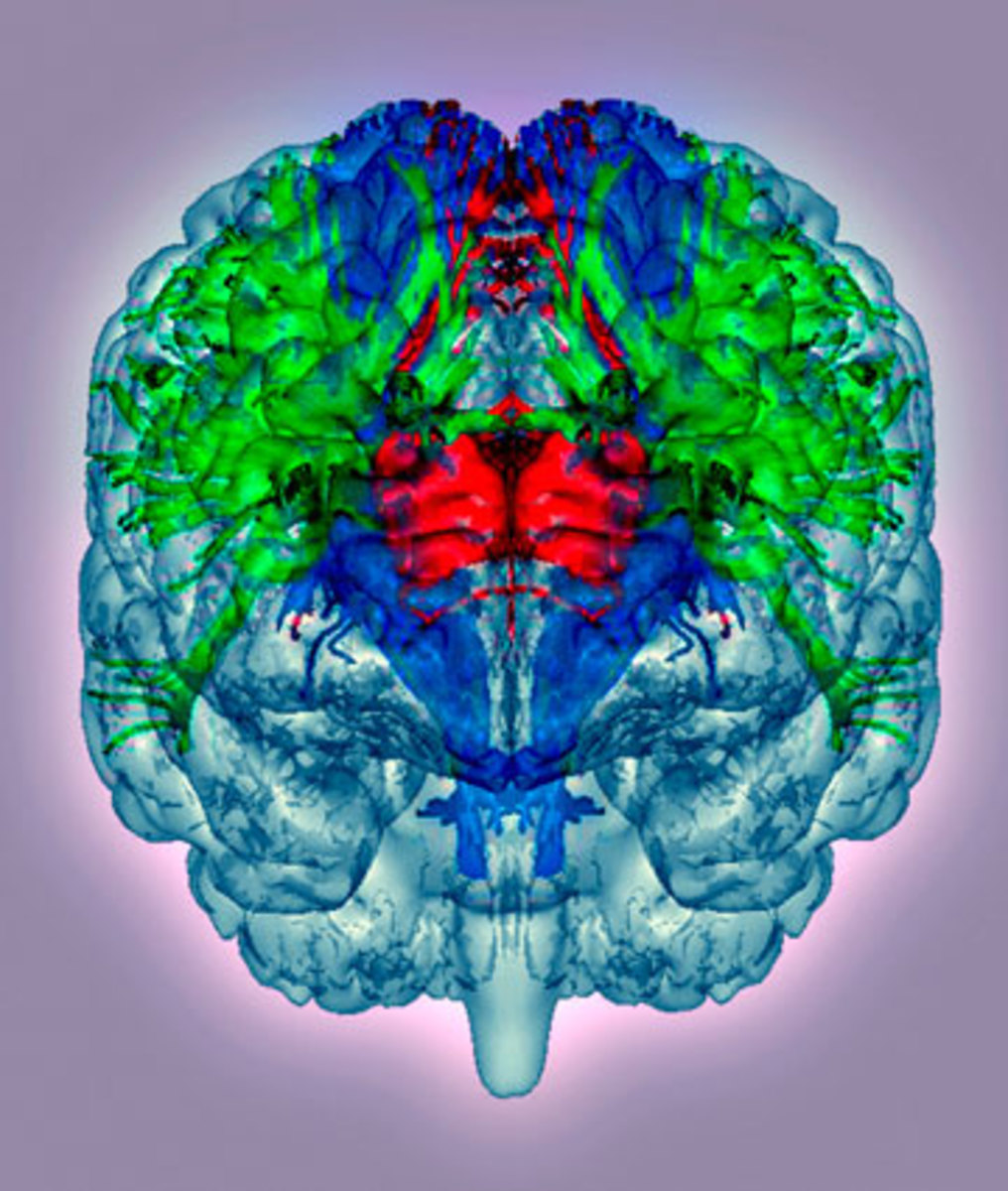

More advanced imaging tools might also give a better window to what’s going on inside the brain, something General Electric is working toward through its $40 million research and development partnership with the NFL. Standard MRI or CT scans do not detect concussions. But a specialized scan like diffusion tensor imaging, for instance, uses water flow in the brain to show damage to the structure and connectivity of its white matter. The goal would be faster scans, tailored to people with larger body mass indices, so the morning after No. 97’s concussion he can be taken for a routine diagnostic scan, as if he had injured his knee.

* * *

Today’s players, like Seahawks cornerback and The MMQB columnist Richard Sherman, describe accepting the risks of football for the career opportunities and the love of the game. It’s true that football will always have risks; the difference in the future could be that a player like No. 97 might have the ability to quantify his risks.

A risk algorithm for each player—not to determine if he will experience long-term consequences from sports-related brain trauma, but rather, an assessment of his risk—may sound far-fetched. “It’s complex to get there. But if it’s pie in the sky now, it doesn’t mean it always will be,” says Stanley Herring, the director of Sports, Spine and Orthopaedic Health for UW Medicine and a Seahawks team physician. “If you could stratify the risk around concussion, you may be able to provide informed decision-making for the patient.”

Hits in the head occur regularly and always pose a danger. But the critical question for football players at all levels is how many hits, and at what magnitudes, trigger long-term damage? Though it’s not a perfect analogy, is there a threshold you shouldn’t pass, like a baseball pitcher being put on a pitch count? And why do some people respond differently to head impacts than others?

The average number of head impacts a player receives per season has been tracked in youth football (around 100), high school football (around 600) and college football (around 1,100), according to published research. For the first time this season, sensors to measure head-impact will be used on four NFL teams as part of a feasibility study run by University of North Carolina researcher Kevin Guskiewicz and supported by the league and the players’ union (only Guskiewicz’s research staff, and the individual players, if they choose, will have access to the data this season).

Diffusion tensor imaging could reveal in real time what is happening inside the brain—much more effectively than MRIs and CT scans do now. (Getty Images/Science Photo Library RM)

Using accelerometers leaguewide, if approved by both sides of the bargaining table, would fill in key blanks about the number and magnitude of hits sustained by NFL players. The data could be used with individuals, to modify playing techniques or as an extra set of eyes to catch big hits that may have gone unnoticed—there are limits to what the “eye in the sky” can see. But it could also play a vital role in answering questions about the long-term effects of head trauma.

Robert Harbaugh, director of the Penn State Institute of the Neurosciences, chairs an NFL subcommittee that is proposing the development of a player database. It would collect the kind of neurological passport we described earlier on every player entering the league, and then retest every three years. This would be a research project, and teams and the league would not see individual data, but funding and player consent are hurdles. Still, says Harbaugh, “if we are ever going to really find out what factors lead to a CTE picture, at some point we have to collect data prospectively and follow players long-term.”

Former players are an important piece of the puzzle, too. Boston University neuropathologist Ann McKee established the presence of CTE among a distinct sample of former players whose brains were donated for research, but what is still missing is how, when and why the disease develops, and the degree to which it is degenerative. The next frontier is diagnosing CTE in living patients, which may be done using a radioactive compound that binds to the signature Tau protein and shows up on positron emission tomography scans. Both the NFL, with partner NIH, and the NFLPA, with Harvard, have proposed long-term studies examining former players’ health.

Some describe the idea of a risk algorithm as akin to a radiation dosimeter (like those used by X-ray technicians or nuclear plant workers) for head trauma, quantifying how much exposure a player has had and how close he is to dangerous levels. There are benefits to the player’s being informed, but also serious questions: How does an NFL player balance risk versus a lucrative career with a short shelf life? How much information will a team be given about a player’s risk levels? Does the player want to know his genotype, something he can’t change, for a gene like ApoE that is believed to be connected not just to recovery from brain injury but also to risk for developing Alzheimer’s? “I can see 10 years from now posing serious ethical dilemmas,” says Robert Stern, professor of neurology and neurosurgery at Boston University School of Medicine, and a member of the NFLPA’s Mackey-White Committee.

* * *

Kids in New Britain, Conn., practicing Heads Up football during a clinic in early October. (Kike Calvo/AP Images for National Football League)

In 2025, No. 97’s concussion diagnosis automatically places him on a short-term injured reserve for concussed players. Similar to Major League Baseball’s seven-day disabled list, he’ll be sidelined for at least a week, without the pressure of the team being down a player.

Falcons president Rich McKay, the chair of the NFL Competition Committee, said this idea has been discussed, and while owners haven’t seen a need for it yet, he could see it being raised again. The Competition Committee has also asked players if they view the three-point stance as unsafe (not right now), and talked about the NCAA’s rule to eject players for helmet-to-helmet hits (fines and a penalty are currently considered enough of a deterrent). McKay wants changes to be evidence-based, such as the 2011 move of the kickoff to the 35-yard line, but the rule of thumb is to keep an open mind.

“Lamar Hunt proved to our league that no idea is a bad idea, because I think he asked us to vote on the two-point conversion maybe 15 times,” McKay says. “And then, one year it got voted in.”

Frames of reference change, and that’s how football will endure this identity crisis.

The NFL sets an example that trickles down to youth leagues across the country, but these players are also the ones who trickle up. In time they may bring with them tackling techniques taught by programs such as USA Football’s Heads Up Football (backed by the NFL), to take the head out of the game, and a different way of thinking about concussions.

“Part of the campaign of awareness is if we begin to treat head injury like we treat heat exhaustion,” Herring suggests. “It’s unthinkable now in practice that you wouldn’t have fluids for your players regardless of sport, right?” Another part of the campaign of awareness is recognizing that risks and benefits may be different for each person. Maybe No. 97’s brother is watching from the stands at Wembley because he took a few months to return to baseline after a second concussion in high school football, and then through a consultation with their family doctor, learned he had one copy of the most risk-prone ApoE e4 allele.

Today's youth players are tomorrow's NFL stars—and the hope is that advances in techniques on the field and technology off of it will make the game safer for them. (Kike Calvo / AP Images for National Football League)

A parent in Fairfield, Conn., asked Roger Goodell the question that has put football at this crossroads—How much is too much?—during the NFL commissioner’s visit to the town’s Heads Up Football youth league practice in August. Specifically, the mother asked, “How many concussions is too many?”