Mean Joe vs. Double O

By Gary M. Pomerantz

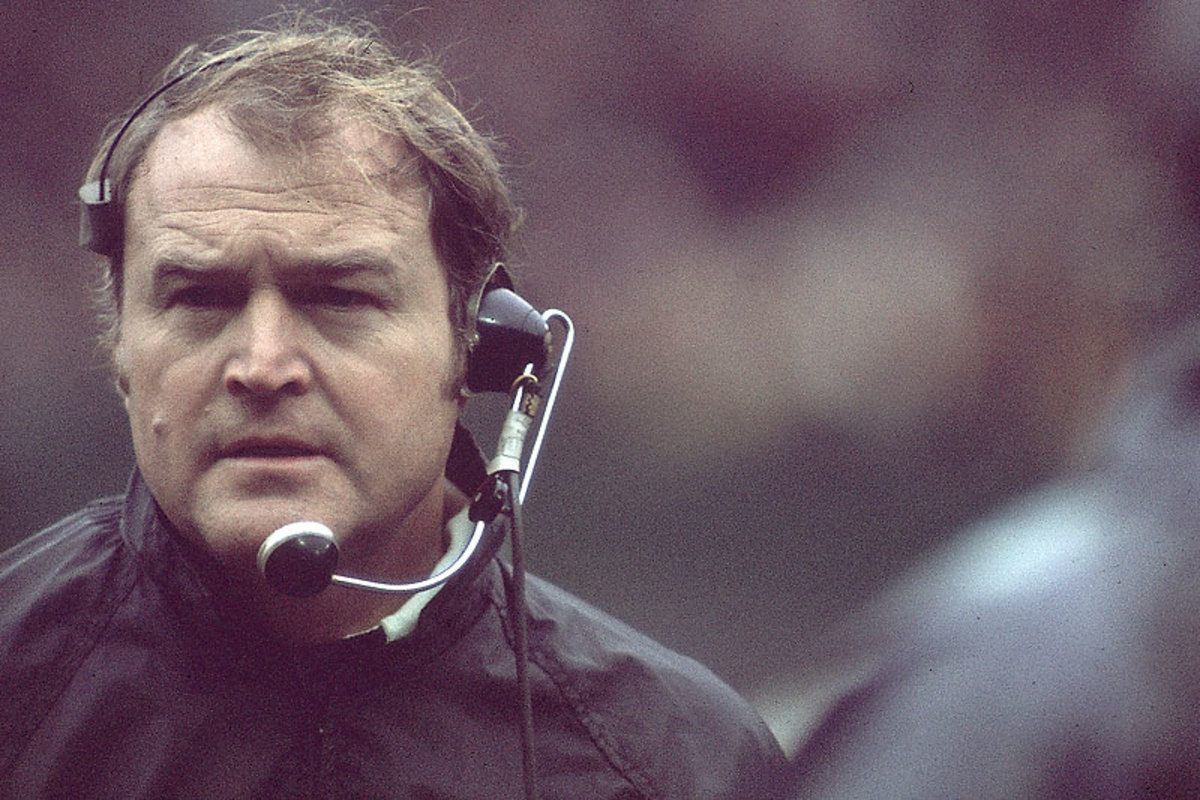

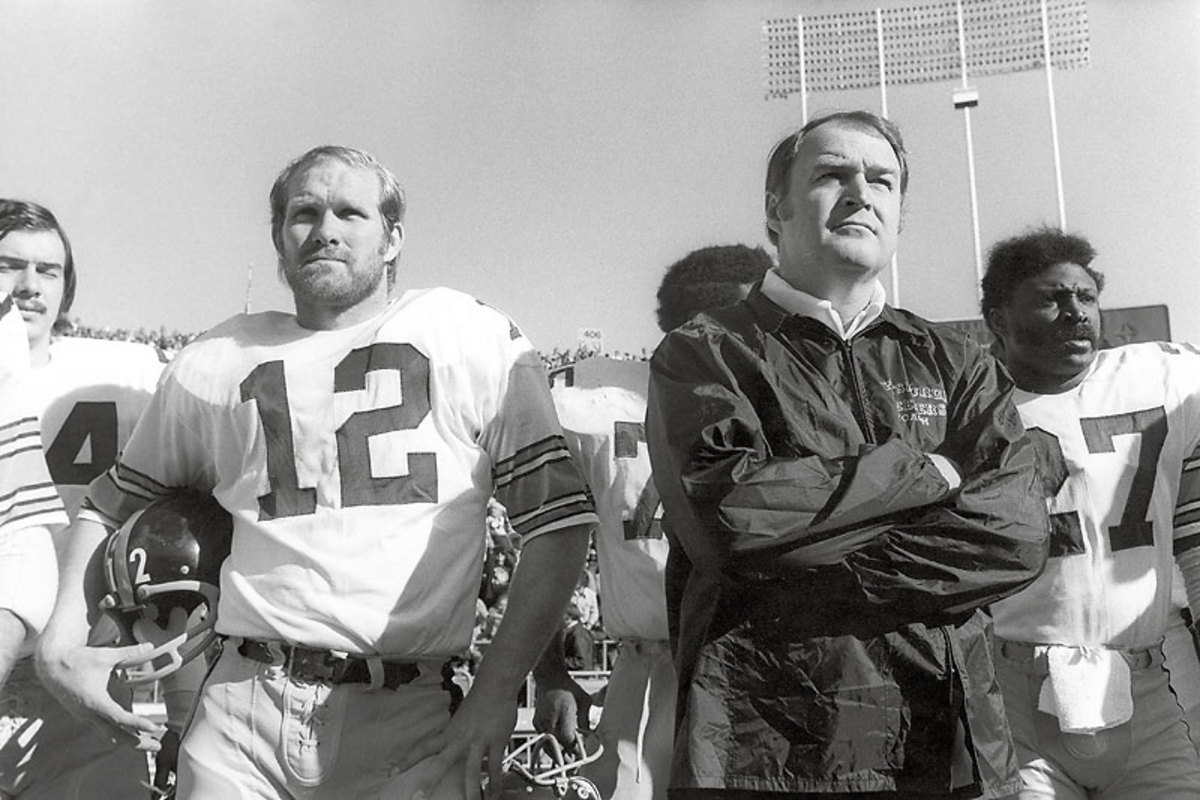

CHUCK NOLL HAD NO SENSE of theater, not an ounce of Olivier in him. He was more like his old coach Paul Brown, a frozen lake in winter. In the Steelers’ locker room before a game, the battle about to be waged, Noll was all focus and details. For him, emotion was anathema. It befogged the intellect, threatened a week’s preparation. It got in the way of execution. Sunday’s games, he said, were won on Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, at practice. “Remember,” Noll said flatly in more than one pregame talk to his players, “let’s make Sunday Fun Day.” But when he heard what John Madden said on television after the Raiders rallied to defeat Don Shula’s Dolphins, 28–26, in the divisional round, purging the two-time defending Super Bowl champion from the playoffs, Noll felt nearly jilted. He heard Madden say that the NFL’s two best teams had just played—the Dolphins and the Raiders—and that comment struck Noll as unfathomably wrong. It stirred his inner Lombardi. And so on the Tuesday before the 1974 AFC title game, the Steelers’ 47 players sat in chairs attached to small writing tables in their usual meeting room, expecting the usual tepid gruel from Noll. But Noll surprised them. He took his best shot, figuring it was early enough in the week so that an emotional rush wouldn’t backfire. He told his Steelers what Madden had said, and then, his eyes tightening at the corners, Noll said that Madden was wrong. “The best team in the NFL,” Noll said, thumping his index finger on a table, “is sitting right here in this room.”

The normally stoic Chuck Noll fired up his troops in relaying John Madden’s claim that the NFL’s two best teams—Oakland and Miami—had played the previous week. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

It took his players a moment to react, to decide whether their coach had just said what he had just said. Then their reaction was like a small dam breaking, hoots and howls, broad smiles and hand slaps, and Franco Harris saying, “Yep!” No player reacted more demonstratively than Joe Greene. He stood so rapidly to pump his fist that his right thigh stuck in the small writing table attached to his chair, and the chair lifted from the floor and toppled.

Noll’s speech ignited Greene. It was like additional gunpowder for an already explosive weapon. Much as he respected Noll, Greene had long craved more emotion from his coach—for his teammates, not himself— and now he had gotten it. It wasn’t what Noll said in the meeting room, or how he said it. It was simply that he said it. It caught Greene, and the entire team, by surprise.

From THEIR LIFE’S WORK by Gary M. Pomerantz. Copyright © 2013 by Gary M. Pomerantz. Published by Simon & Schuster, Inc. and reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. (Click on book image for purchase information.)

Greene would be voted the league’s defensive player of the year in 1974, and now, at the pinnacle of his professional career, he entered a three-week period during which he terrorized playoff opponents. John Vella, a Raiders offensive tackle, studied Greene on film before the AFC title game. “I looked at the way he carried himself. He was their leader,” Vella said. Madden showed the Raiders film of Greene and Jack Lambert acting as ruffians, shoving opponents after plays, pushing off their face masks to stand up. Madden didn’t offer comments. He thought their actions spoke loudly. “You could tell how proud Joe was,” Vella said, “and that the rest of the Steelers looked up to him for leadership.” Raiders receiver Mike Siani had the same feeling: “Joe was a beast, an absolute beast. He was a destructive force.” Steelers line coach Dan Radakovich later said that during the 1974 NFL postseason, “Joe Greene was the greatest defensive lineman that ever lived.”

* * *

Oakland Coliseum, pregame. Long and lean, Steelers defensive end L. C. Greenwood stretched out on a folding chair in a hallway outside the visitors’ locker room. There, on a small TV, he watched the Vikings and Rams in the other conference’s title game. Just then, Raiders offensive linemen Gene Upshaw and Art Shell happened by, like two All-Pro ships passing. “Whatcha watching, L.C.?” Upshaw asked. Greenwood had none of the puffed-up bravado of his defensive linemates Ernie “Fats” Holmes, Dwight “Mad Dog” White, or Mean Joe. But even Greenwood couldn’t resist this one. “I’m just looking,” he said, “to see who we’re going to play in the Super Bowl.” The Raiders’ two All-Pro ships passed without reply.

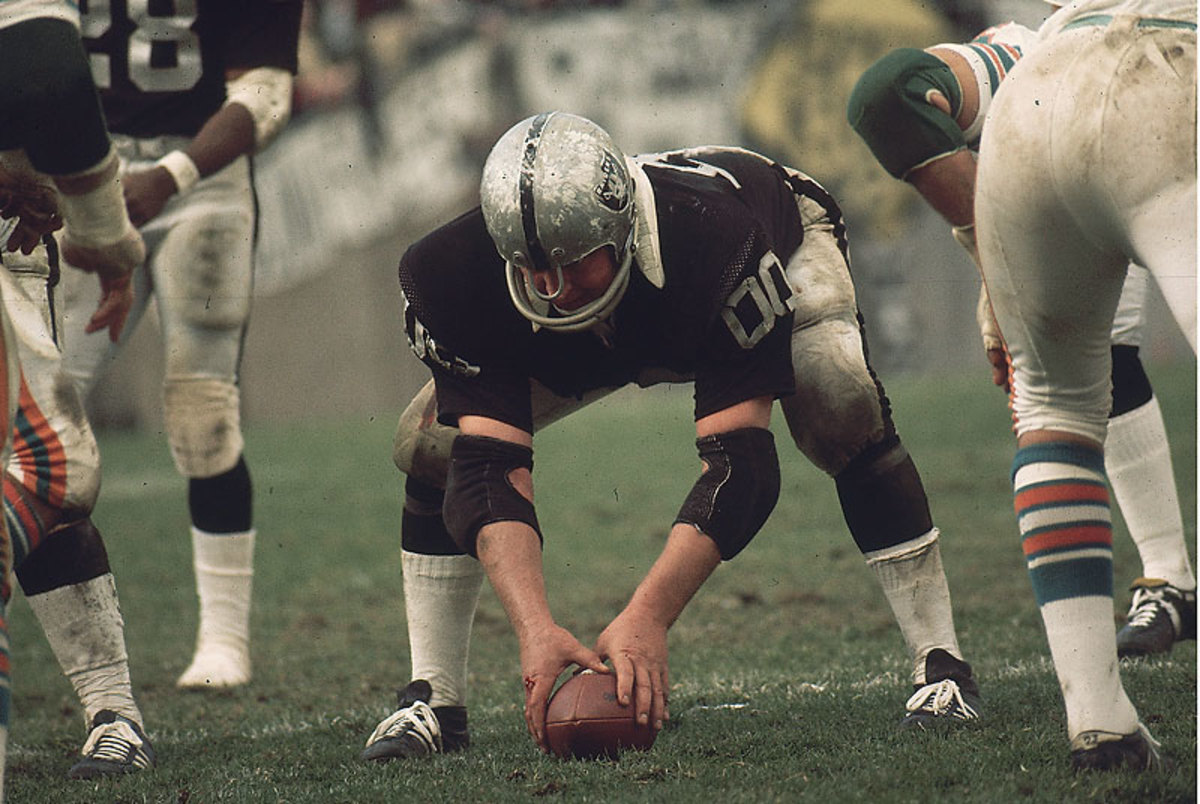

Joe Greene vs. Jim Otto: Here was the AFC title game’s defining matchup, at the line of scrimmage—Greene at the apex of his career, and the Age of Otto, fading to darkness, in its 15th season and 223rd consecutive (and final) start. An opponent once said that looking through Otto’s face mask was like looking at a gargoyle. Otto, the Raiders’ center, had a massive Prussian head, a perpetual sneer, and dark, menacing eyes. His nose, broken more than 20 times, curved like the letter “S,” and his wife sometimes rearranged it in the stadium parking lot after games as if it were living room furniture. He wore a size 8 helmet, big as a bucket, largest on the Raiders, a battlefield relic with the signature pirate with an eye patch on its side covered over by a white splotch—the paint scratched off from Otto’s violent collisions with the likes of Curley Culp, Ernie Ladd, Buck Buchanan, Merlin Olsen and Mean Joe Greene. Greene once railed at Otto on the field and Otto simply said, “How’s your wife and children, Joe?” This was Double O’s way of saying, “Shuddup and play!”

By the time of the 1974 playoffs, Jim Otto’s helmet, not to mention his body, bore the scars of 15 seasons in the trenches. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

So deep was Otto’s immersion in football, his wife once heard him calling out line signals in his sleep. He was the quintessential Raider, the standard-bearer who insisted on holding the football in every Raider team photograph from 1960 through 1974, reminding young teammates that centers were supposed to hold the football. Early on he asked the Raiders for jersey number “00” because, he said, his last name began and ended that way (aught-oh). Double O became his moniker, and the zeros on his jersey looked like two eyes opened wide. He wore a face mask with two simple horizontal bars, a look more common to wide receivers and quarterbacks, none of that cagelike protection many linemen used. Opponents gouged his eyes, and after some games Otto looked in the mirror and thought he’d been in a knife fight. But he was wily, a tactician, and through the years he doled out more pain than he received. Siani saw Otto return to the sideline once in 1973, his forehead oozing blood that streamed over the bridge of his nose, a screw inside Otto’s helmet the cause. The team trainer approached Otto to help stop the bleeding. “Get away from me!” Otto growled. Siani thought, Double O likes it! He thinks the blood will intimidate his opponent! It intimidated Siani.

For six seasons Greene had done battle with Otto. “I mean, you hit him in the head and your helmet would just . . . ring!” Greene said. “You had to deliver a blow with your helmet, and hitting him with your helmet was not something that you cherished. First, you had to get your mind right, as we say.”

Jim Otto. (Long Photography Inc./SI)

Otto had stayed too long. A week shy of his 36th birthday, his younger teammates deferentially called him Pops. His body had been shattered by the game. He had endured nine knee surgeries. The interior of his knees ground, bone-on-bone. Surgical scars crisscrossed his legs like train tracks. He suffered terrible pains in his back. His fingers, stepped on too often, were misshapen and throbbed. He’d grown nearly dependent on the painkiller Darvon and muscle relaxers. During the latter half of the 1974 season, ligaments pulled and creaked in his right knee, which trainers drained thrice weekly. Doctors told him the knee needed a bone graft reconstruction. Otto went home to bed after practices and his wife iced his legs. She awoke in the darkness of three a.m. and put more ice on his legs. Then Otto got up at seven, the swelling much improved, and headed off to practice. Tackle John Vella said, “His leg and knee didn’t look like a leg and knee. It looked like a blob, just one continuous leg with no form. I’d see that and think, ‘That’s kind of where his knee should be.’ ” Each week in the training room Vella saw bloody fluid form on Otto’s knee and couldn’t bear the sight. Vella: “You couldn’t believe what he put his body through to play. Then he would do the same thing the next week. It was like you thought to yourself, Are you really going to complain about anything physically when you see what Otto is going through?”

As the postseason started, Dan Jenkins wrote in Sports Illustrated that the Steelers were the “only playoff team without a quarterback,” another dig at Terry Bradshaw. Approaching the AFC title game, the Steelers’ offensive strategy was simple: They would run the ball. All week they had studied films of how other teams had pounded the run against the Raiders, the Dolphins for 213 yards, the Cowboys for 144, and Denver for 292. The Steelers would run Harris and Rocky Bleier over and over, leaning on tackle traps, using the mobility of Jon Kolb and Gordon Gravelle. Bradshaw, with a 16-day growth of red beard, would throw minimally, perhaps 15 times. “All of them ran on Oakland,” Bradshaw said, “so we knew we could, too.”

His leg and knee didn’t look like a leg and a knee,” John Vella said of Otto. “It looked like a blob, just one long continuous leg with no form. You couldn’t believe what he put his body through to play.

On the Raiders’ first play from scrimmage, Fats Holmes didn’t bother with the defensive huddle. He stood over the football at the line of scrimmage, all wired up, and howled at his Raiders opposite. “Hey, EUGENE!!” No response. “EU-GEEEEEENNNEEE!” Nothing. “Hey, UPSHAAAAAAAW!!” From the offensive huddle, Gene Upshaw looked at him. “I’M GONNA KICK YOUR ASS!” Holmes shouted. In the defensive huddle, Greenwood laughed, knowing that his weeklong teasing had worked. “Far out, Ernie!” Greenwood said.

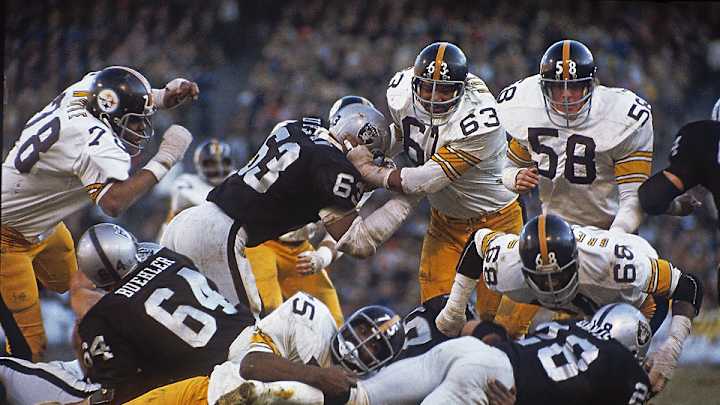

Oakland running back Clarence Davis took the first handoff and ran left, behind Upshaw. Holmes slammed into the running back. Davis gained four yards, and it would be the Raiders’ longest run of the day. For good measure, in a pile of players, Holmes spat in Upshaw’s face. Two plays later, on third and five, Greene aligned in the Stunt 4-3, threw Otto to the ground with one hand, leaped with both arms skyward to block a pass that Stabler opted not to throw, and then grabbed the quarterback by his right hip pad and spun him to the ground for an 11-yard loss. As was their habit, the Raiders continued to run left during the first half, behind Upshaw and Shell. That sent the action toward Holmes, White, and linebacker Andy Russell; each time, the Raiders’ runners got mauled by gang tackles. In the huddle, Ham, the linebacker on the other side, playfully told Russell that he was bored. “Let me take a few shots over on your side,” Ham said, though his own big moments were soon to come.

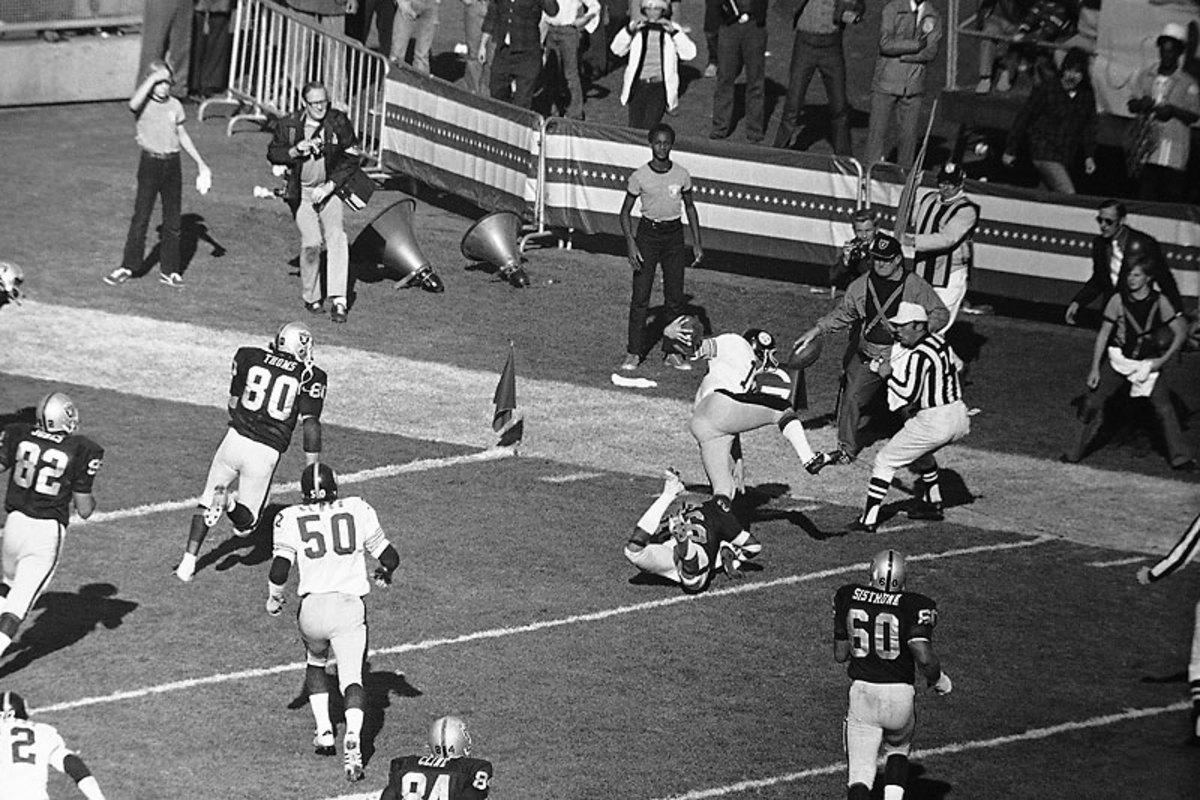

The Steelers’ plan was to run the ball at the Raiders rather than ask Bradshaw to win with his arm. (Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated)

Greene played as if a Super Bowl appearance depended on him, and him alone. After one run, Greene, consumed by emotions, turned on Otto. He kicked him in the groin and dropped him. In an earlier game between the teams, Raiders guard George Buehler’s hand had snagged accidentally inside Greene’s jersey. Mean Joe believed Buehler was holding him and took corrective action, kicking wildly at Buehler. Pops Otto had rushed in that day, protectively, saying to Greene, “Knock that off!” But now it was Pops’s turn, and this time Greene’s swift cleated kick did not miss its mark. Beneath his breath Otto muttered, “You dirty . . .” Otto was on the defensive, vulnerable. His injured right knee ruined his blocking posture and balance. Greene, meanwhile, complained to officials that Otto was holding him. Otto replied with a snarl: “The only person I hold is my wife!” In the week leading up to this game, Buehler had prepared only for Greene. “I didn’t hear anything anybody was saying,” Buehler said. “I just watched films and thought of Joe.” Now, with the Raiders intending to send running back Marv Hubbard up the middle, between Buehler and Otto, Greene moved into the gap between them in the Stunt 4-3 and took his three-point stance, his nose inches from the ground. “I knew I had to get to Joe quickly because he was my assignment,” Buehler said. “But Joe leaped back and I went falling on my face, and Hubbard told me, ‘I’ve never been hit so hard.’ ”

Holmes (63), Lambert (58) and the rest of the Steelers D held Oakland to just 29 yards on 21 carries. (Arthur Anderson/Getty Images)

The Steelers took a 10–3 lead midway through the second quarter—or so they thought—when Bradshaw lobbed an apparent eight-yard touchdown pass to John Stallworth at the far left edge of the end zone. Cornerback Nemiah Wilson held Stallworth’s right hand as he trailed half a yard behind, and Stallworth made a one-handed catch, cradling the ball with his left hand. But the head linesman ruled Stallworth out of bounds, a call TV replays proved incorrect. (The NFL did not allow instant replay reviews at the time.) “I don’t mind another player shaking my hand, but not when I’m trying to catch a pass,” Stallworth said after the game. Bradshaw threw an interception two plays later, and Stallworth, still furious over the earlier call, got penalized for a late hit on the interception return. The Raiders drove to the Steeler 23 and, with a minute left in the half, Stabler threw a 22-yard pass to receiver Cliff Branch, who beat cornerback Mel Blount and stepped out of bounds at the 1-yard line. As Otto had set up for pass protection on the play, pain shot through his right knee. He lifted his right leg and tried to balance himself on his left leg while stopping Greene’s furious rush. Greene fell over him, and Otto was penalized for tripping, negating the gain and costing the Raiders a possible touchdown before the half. Madden said the Raiders hadn’t been cited for a tripping penalty in five years. Lambert blocked George Blanda’s 38-yard field goal attempt, and so the half ended at 3-all. In the first half the Raiders’ offense had just two first downs and 65 total yards.

Greene’s swift cleated kick did not miss its mark. Beneath his breath Otto muttered, ‘You dirty . . . ’

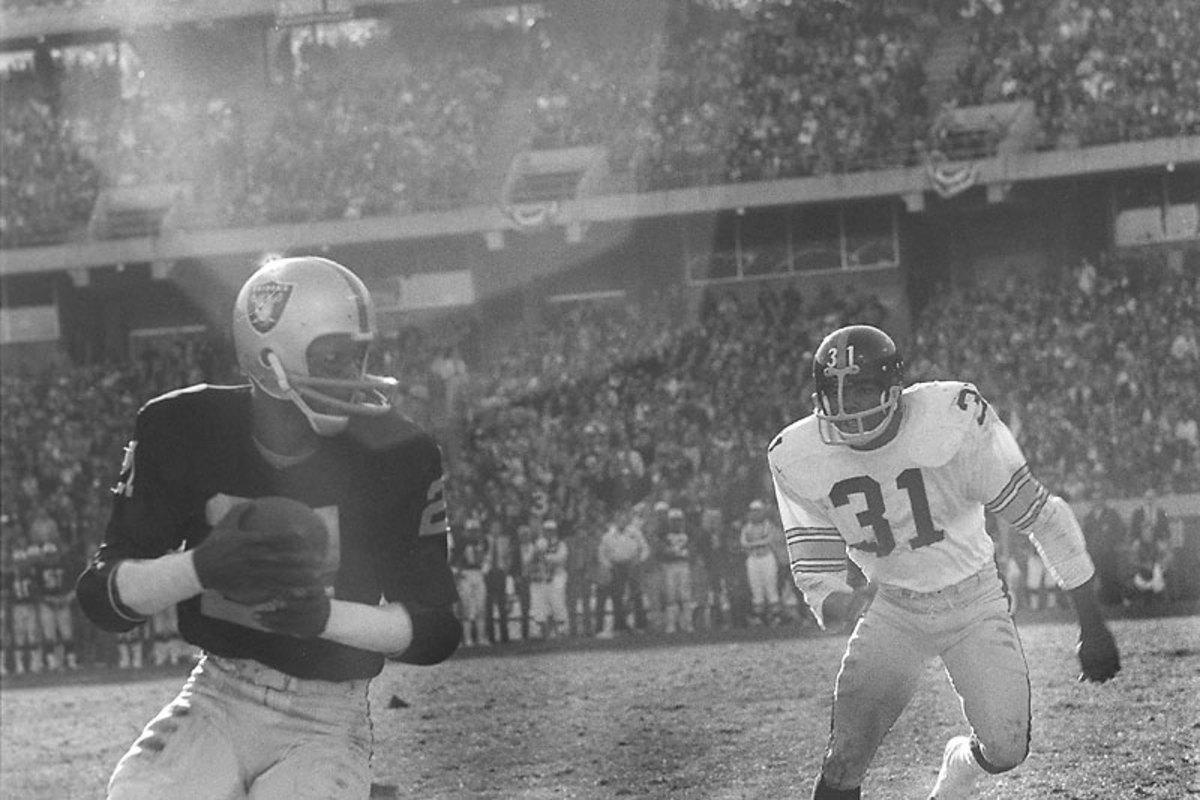

The Steelers’ defense continued to punish Oakland running backs in the third quarter. By game’s end, the Raiders would gain only 29 yards on 21 rushes, a stunning performance by the Steelers’ defense. “They stopped Oakland’s running,” Oakland Tribune sports editor Bob Valle would write, “with a Steel Curtain the Russians couldn’t penetrate.” But the Steelers’ offense wobbled, keeping the game close. When Branch, the Raider receiver who led the NFL with 13 touchdown catches, turned Blount inside out and caught a 38-yard touchdown pass from Stabler, the Raiders led 10–3 with five minutes left in the third quarter.

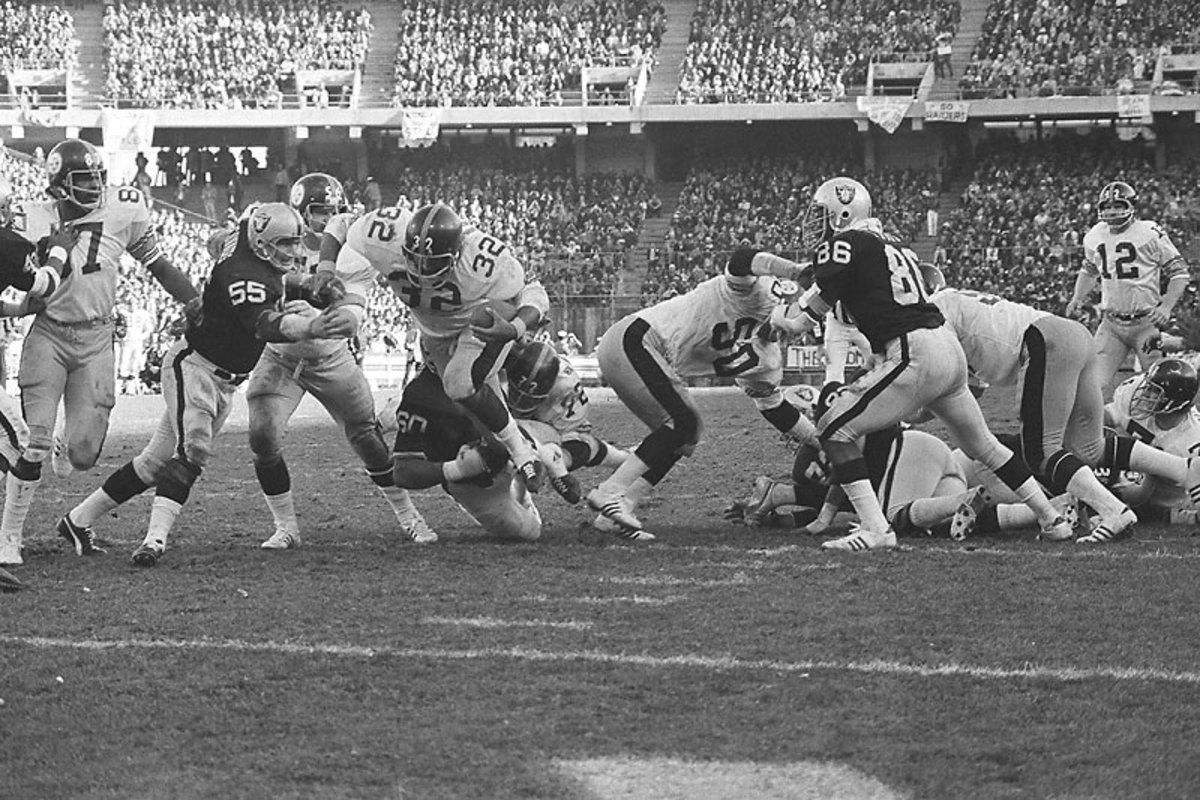

Then the Steelers opened up the ground game, their offensive line asserting control, Harris and Bleier running eight times in a time-consuming nine-play drive. Harris ran for a touchdown from eight yards on a tackle trap, tying the game at 10 early in the fourth quarter.

Now came Ham’s big moment. With Russell, Lambert and safety Glen Edwards blitzing, Ham cut in front of running back Charlie Smith to intercept his second Stabler pass of the game, this one at the Oakland 34. He returned it 25 yards. Up in the press box, Steelers owner Art Rooney, the Chief, wearing his lucky cap and his favorite old overcoat, studied the replay on the television monitor, without comment. Bradshaw, three plays later, lasered a six-yard touchdown pass to Lynn Swann slicing across the middle for a 17–10 lead. The Chief watched the replay of that one, too, the cold stub of his cigar stuck in his mouth. He revealed no emotion, though his insides roiled.

Relying on Franco Harris (above) and Rocky Bleier, Pittsburgh pounded the Raiders on the ground until they broke in the fourth quarter. (Michael Zagaris/Getty Images)

Bud Carson, the Steelers’ defensive coordinator, mixed coverages and blitzes that confused Stabler all afternoon. But Branch beat Blount again, this time for a 42-yard gain. Had Lambert not tackled Branch in the open field at the Steelers’ 24, he might have scored the game-tying touchdown. Carson snapped. He benched Blount for the remainder of the game, replacing him with rookie cornerback Jimmy Allen, who fared well against Branch. Blanda’s field goal cut the Steelers’ lead to 17–13.

Bradshaw would throw only 17 passes in this game, completing eight, for 95 yards. By design, he put the ball in the hands of Harris and Bleier. Harris would run for 111 yards, Bleier for 98. On one sweep, Gravelle found himself at the bottom of a pile in front of the Raiders’ bench and got an earful of Madden screaming at officials. As he excavated himself from the tangled players, Gravelle saw Madden, in mid-tirade, look at him, smile, and wink, and then resume screaming at officials. “I thought to myself,” Gravelle said, “I like that guy!”

Stabler got one last chance. Trailing by four points with 1:48 to play, he needed to cover nearly 70 yards for the winning touchdown. On first down, Greenwood, in his gold high-tops, flashed into the pocket and sacked him for a nine-yard loss, but cornerback J. T. Thomas was called for holding on the play. In the ensuing defensive huddle, Russell told Thomas, “Don’t let the officials intimidate you. Keep playing your aggressive game.” On the next play, Stabler’s pass protection collapsed at the Oakland 32, a blitzing Russell closed in on him, and he lofted a pass downfield that Thomas intercepted. With arms and legs pumping, Thomas raced down the left side, past a forlorn Madden, 37 yards to the Oakland 24. Moments later Harris shot up the middle for a 21-yard touchdown with 52 seconds left. The Steelers’ 24–13 victory was sealed, as was their date in Super Bowl IX against the Minnesota Vikings at Tulane Stadium in New Orleans two weeks hence.

Mean Joe vs. Double O

Bradshaw had lost Noll’s trust during the season but repaid the decision to start him in the AFC title game. Four Super Bowl titles later, it would be hard to fathom that the Steelers nearly gave up on Bradshaw for good in ’74. (Michael Zagaris/Getty Images)

Pittsburgh had fallen to the Raiders in the divisional round the previous season and knew if they wanted to make it to the Super Bowl they’d have to go through Oakland to do it. (AP)

Cliff Branch proved to be the Raiders’ most dangerous threat that December afternoon—nine catches for 186 yards and a touchdown. Here rookie Donnie Shell closes in. (Michael Zagaris/Getty Images)

Harris carried 29 times for 111 yards and two touchdowns, both in the fourth quarter. (AP)

Swann, one of four Steelers from the ’74 draft class who would make the Hall of Fame, hauled in the go-ahead touchdown in the fourth quarter. (Michael Zagaris/Getty Images)

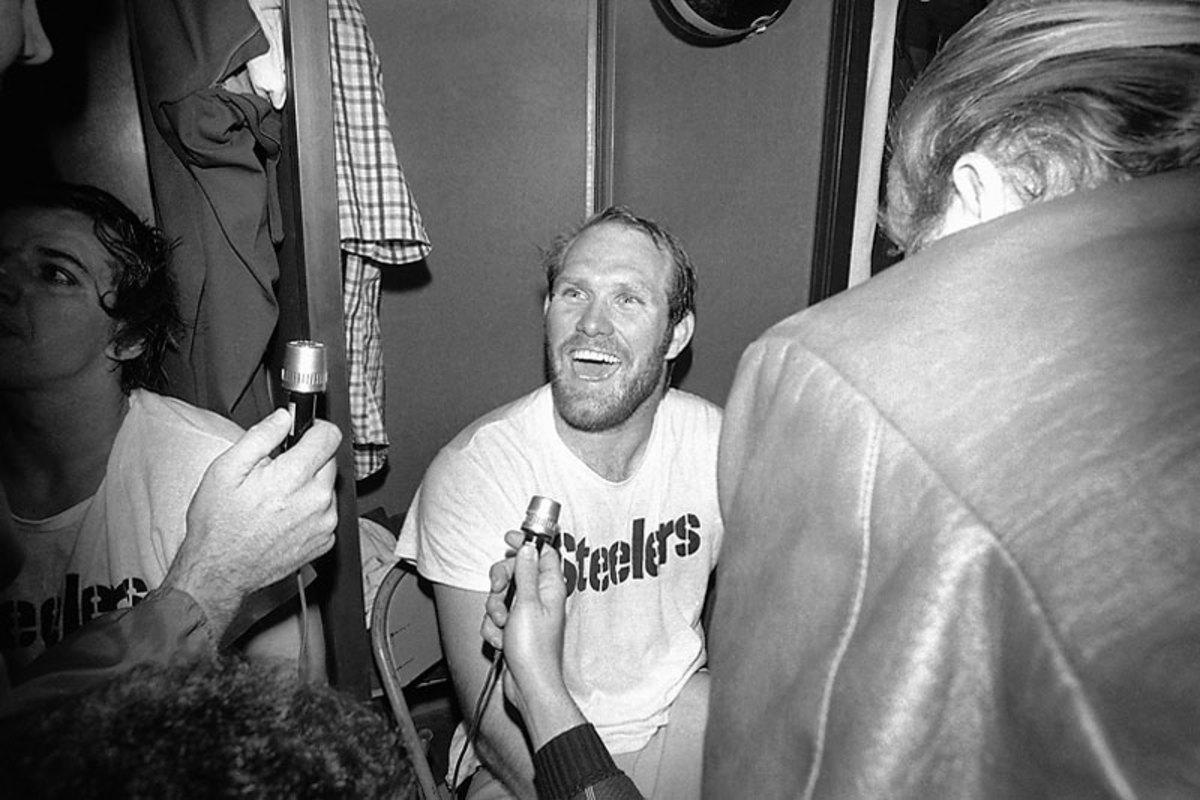

A vindicated Bradshaw was all smiles in the winning locker room. (AP)

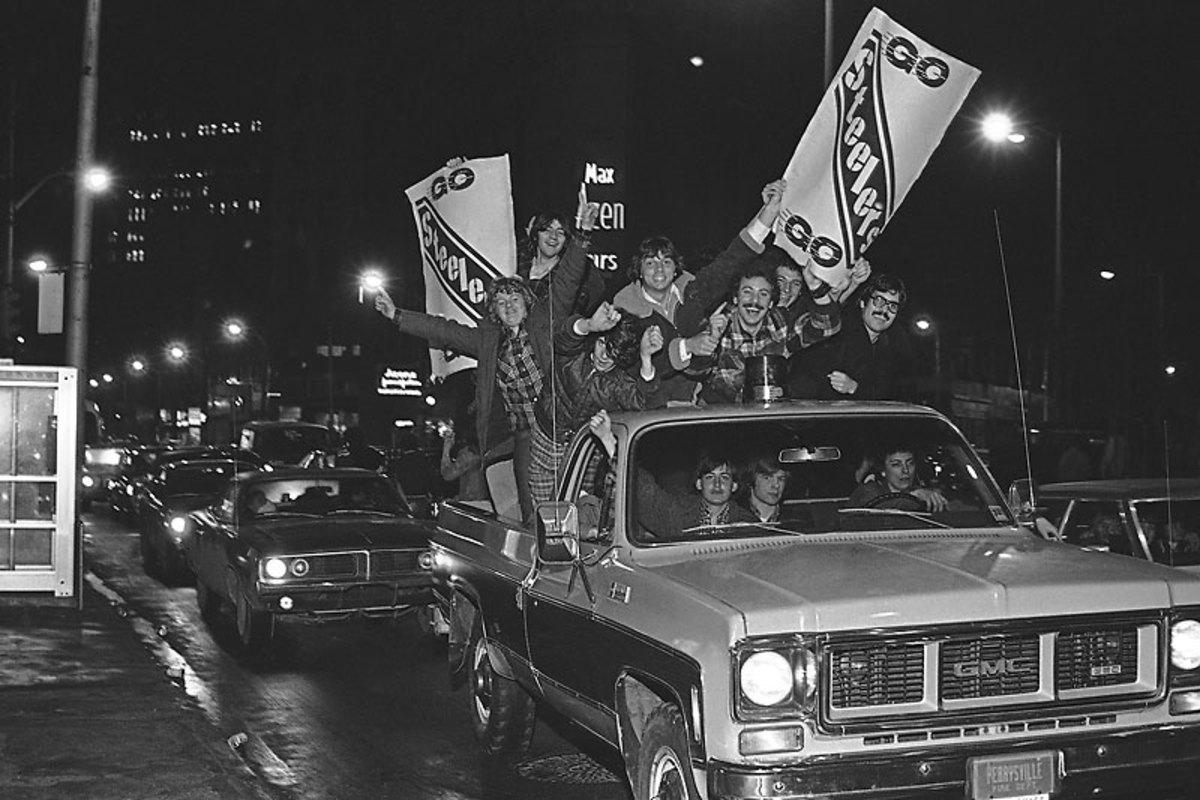

Back home, the Burgh erupted in celebration of the Steelers’ first appearance in a league championship game; four decades on they have more Super Bowl titles than any other team. (AP/GRG)

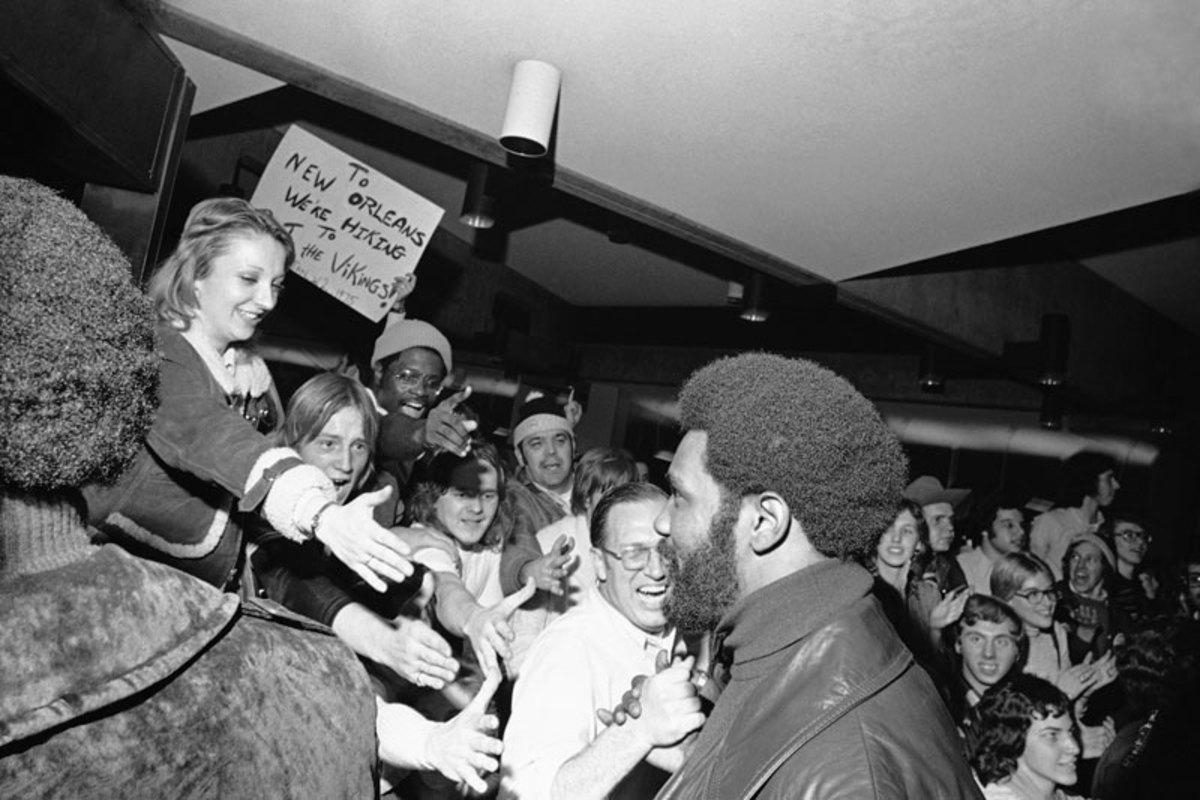

Greene wasn‘t so mean when he greeted the hometown crowd. His ’74 postseason was one of the most dominant stretches for a defensive player in NFL history. (AP/GRG)

* * *

Many years later Joe Greene would say that only once in his 13-year NFL career had he and the Steelers’ defense been in the zone—where the unit could do no wrong—and that was during the 1974 AFC title game. Oakland’s rushing numbers, 29 yards on 21 carries, an average of 1.4 yards per attempt, became a statistic he would never forget. “The zone is a place that you rarely visit. It’s not someplace you go every week,” Greene said. “The zone is sacred ground.”

In the locker room at Oakland, though, when the AFC title game victory was brand new and the team’s joy was at its purest, these Steelers hugged and preened and busted each other’s chops, the camaraderie that was always the most satisfying antidote to the game’s sufferings. Finding his way to the cameras, Swann said, “Going to the Super Bowl feels like a million dollars. Wait, make that twenty-five thousand dollars, to be exact.” Backup quarterback Terry Hanratty let loose a few happy roars and then later, always the jokester, said, “I think I’ll report to the trainer tomorrow and soak my vocal cords in the whirlpool.”

The Chief, naturally, searched for Joe Greene. He reached for Mean Joe’s hand. “Congratulations, Joe,” he said. “No, Chief,” Greene replied. “Today the congratulations go to you.”

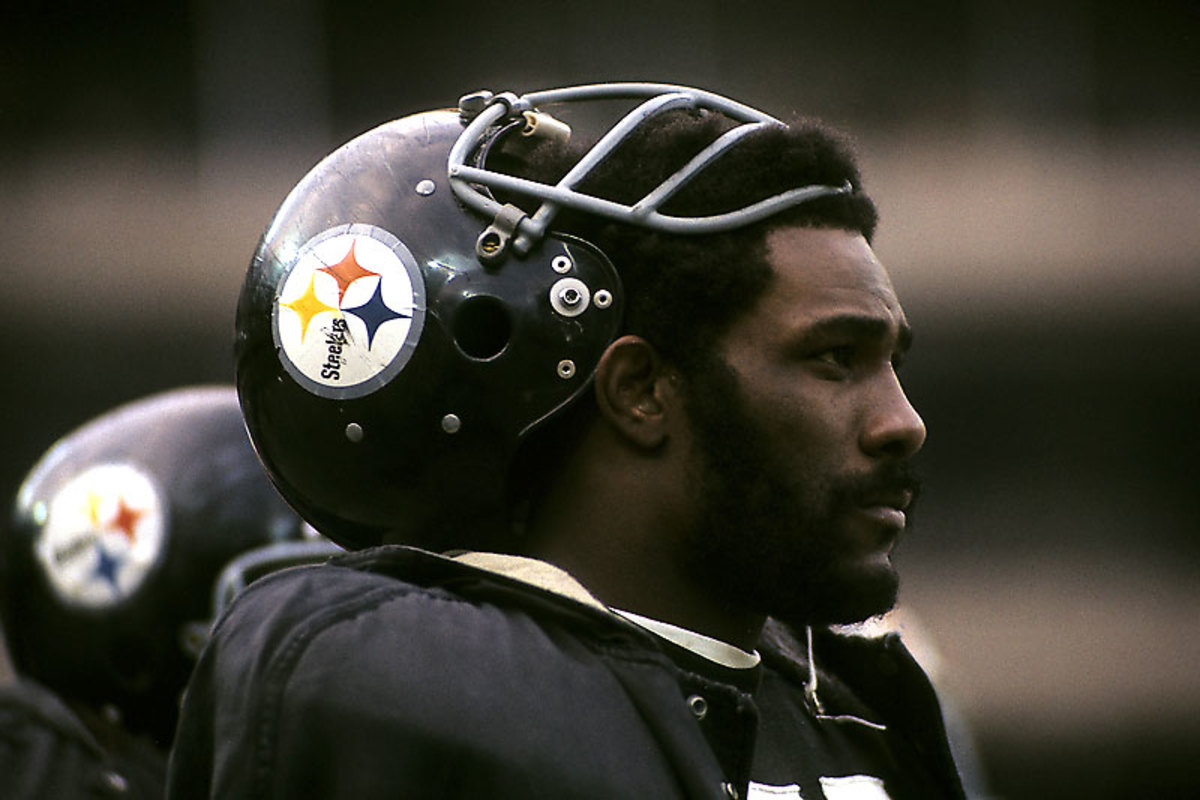

Joe Greene. (Tony Tomsic/WireImage.com)

Gary M. Pomerantz is a nonfiction author and journalist and a visiting lecturer in the Department of Communication at Stanford. His other books include

,

and the

Notable Book of the Year

.