Breaking Real Bad: Inside the Sam Hurd Drug Case

By Michael McKnight

Update—Nov. 13, 8:00 p.m. ET:Taking into account Hurd’s status as a first-time offender, U.S. District Court judge Jorge A. Solis sentenced Sam Hurd to 15 years in prison, followed by five years of supervised release. Under federal guidelines Hurd will have to serve 85 percent of that sentence before being eligible for parole. Hurd’s mother said he would appeal the sentence.

Update—Nov. 13, noon ET:With Sam Hurd's sentencing set for Wednesday, Michael McKnight has a few updates on where the case stands, including details of the loss of a witness and reactions to Tuesday's story.

PART I

At 7:35 p.m. on Dec. 14, 2011, Sam Hurd’s black Escalade arrived in a light rain outside a Morton’s restaurant in Chicago and backed into a street space near the entrance. The Bears’ receiver, then 26, had driven to the steak house following practice to meet with two Mexicans who moved cocaine for one of their country’s most violent cartels, the Zetas—a murderous army known for beheading its enemies and dumping their bodies on public streets.

It had been a tense workday for the Bears, who had just lost three games in a row after starting the season 7-3, and after practice Hurd had called one of the Mexicans, Manuel, and asked if he and his cousin would come to Hurd’s suburban Lake Forest home instead of dining out. But Manuel (not his real name) had gently insisted on the restaurant, suggesting the Morton’s near O’Hare because the traffickers were headed that way to pick up cash from an incoming courier.

With his gangly strut, Hurd followed a hostess through the bustling Morton’s dining room and was seated at table 54. When the two Mexicans arrived a few minutes later, it became clear that Manuel’s cousin—a stone-faced man wearing a black leather jacket and holding an expensive cowboy hat in one hand and a white gift bag emblazoned with HAPPY BIRTHDAY in the other—was in charge. The diminutive Manuel, who had only spoken with Hurd on the phone, shook the player’s mammoth right hand as the cousin introduced himself in a soft voice: “Juan.”

“It’s nice to meet you, Juan,” Hurd said.

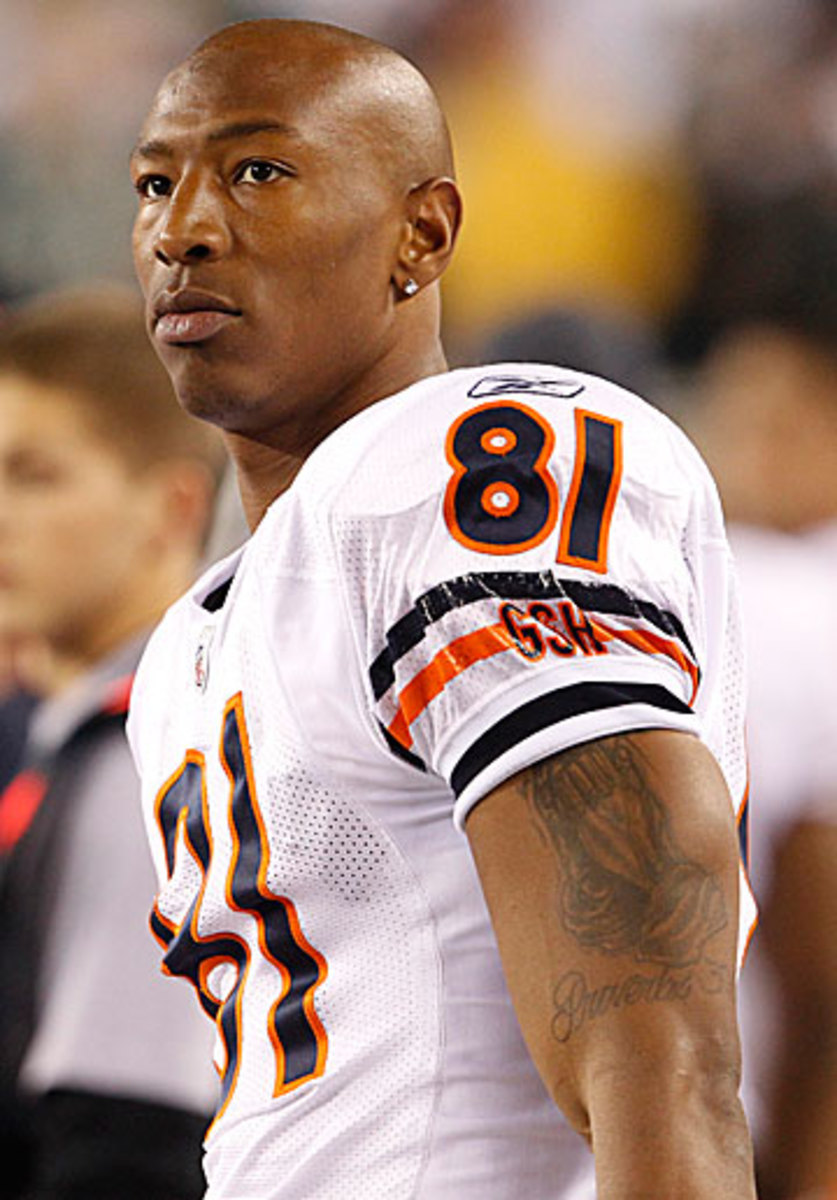

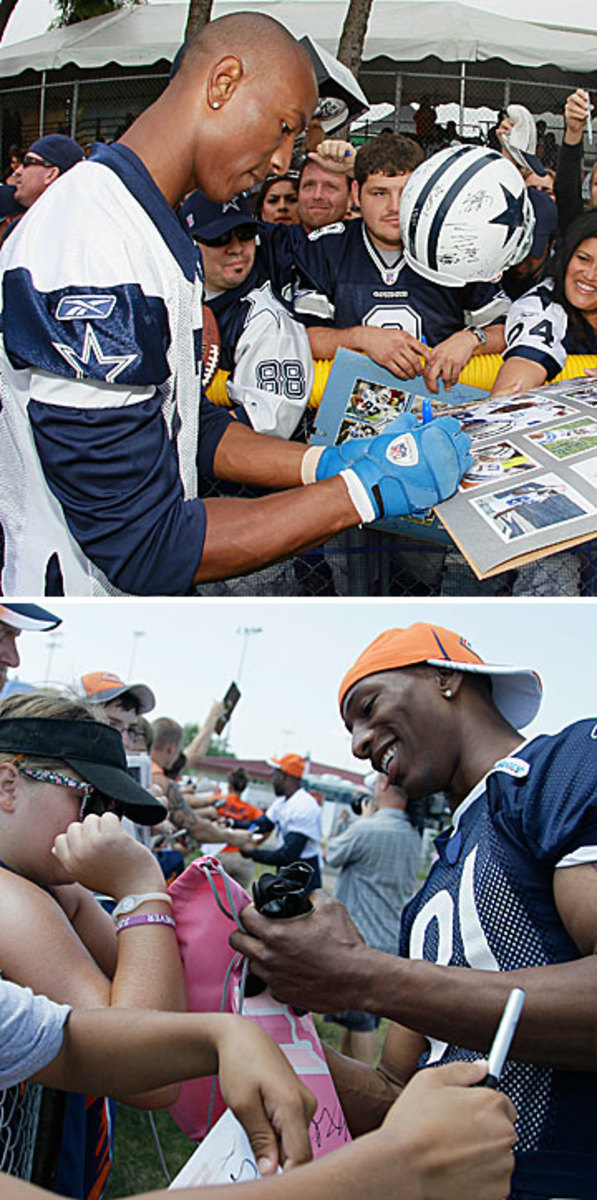

Sam Hurd signed with the Bears in 2011 after five seasons with the Cowboys. (Nuccio DiNuzzo/Chicago Tribune/MCT via Getty Images)

They sat. Within two minutes Juan (also a pseudonym) got to the point: “My cousin was telling me that you’re interested in getting some stuff up here. ... Now, where did you wanna pick it up?”

“Where?” Hurd asked in his deep baritone.

“Did you want it all the way here, or in Dallas?” Juan said. “If we get it in Dallas it’s cheaper.” Then Juan named his price: “Veintidós.” Twenty-two thousand dollars per kilo. “How many we looking at?” How many kilos do you want?

“Right now?” Hurd asked. “I can do five, but I can do as many as—by next week, 10 in a week, all the time. Or more. ... Thing is, I’ve never had nobody to provide it.”

“O.K.,” Juan said. “And see, what I’m getting right now is really good stuff. I mean this is like, uncut, 98 percent pure cocaine coming in from Colombia, and it’s just some good s--t. ... So, um, if you say you want it here, I can do it for 26.” Twenty-six thousand per kilo.

Hurd haggled a little, knowing the price went down the more kilos he ordered. “I’ll be at 50 [kilos] a week soon, because they go like that,” he said. “I just don’t have—I just never had nobody that could give me more than four a week.”

“Quantity is not a problem,” Juan said over the din of the room. “I mean, I can get you—”

Hurd cut him off. “Quantity was always a problem for me,” he said, sounding every bit the drug lord U.S. news consumers would soon imagine him to be. Translation: Sam Hurd could import, mark up and sell as many kilos of cocaine as he got his hands on—he just couldn’t get enough of it.

As with most things in Hurd’s life, however, things were not what they seemed to be behind Morton’s rain-beaded windows that night. The three men seated at the table next to him—the guys who looked like lawyers on an expense-account splurge—were undercover federal agents. And the 77-minute conversation that Hurd had just begun with Juan and Manuel was being recorded.

Today Sam Hurd is sitting in a federal detention center in Seagoville, Texas, awaiting sentencing after he pleaded guilty in April to a single count of conspiracy to traffic narcotics. The alleged amounts of cocaine and marijuana in his case are so massive, the U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services Department has recommended that Hurd—husband to his college sweetheart, father to their one-year-old girl, still unanimously loved by friends and former teammates throughout the NFL— be sentenced to life in prison without parole when he next appears in federal court, on Nov. 13. Had Hurd received the 50 kilos per week he suggested at Morton’s, he would have poured nearly three tons of cocaine onto Chicago’s streets each year.

But let’s go back to a time before things got hairy, before the disastrous decisions that placed Hurd in the crosshairs of federal law enforcement. And long before Hurd became entangled with the two men whose lies, he says, have pushed him to the brink of spending the rest of his days behind bars. Among the few things not in dispute as his sentencing approaches is that Sam Hurd played for the Cowboys from 2006 through ’10 and for the Bears in ’11. For the last three or four years of his NFL career he smoked high-grade California marijuana “all day, every day, and I didn’t want to hear anyone trying to tell me I had a problem,” he says.

“Whatever was considered the loudest weed in California—I wanted a notch above that,” Hurd explains in a white cinder-block interview room in Seagoville, with only a hint of the pride he used to express on the subject. “I had educated myself on different strains and potencies and growing techniques. I was very selective. It was like wine.”

Most of the marijuana Hurd had shipped in from California, he says, he smoked himself or shared at cost with friends, including 20 to 25 teammates spanning his five years with the Cowboys. A two-year federal investigation into Hurd’s activities conducted by the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) division has produced no evidence that Hurd made a profit selling this marijuana. “I was what you call love,” he explains, using the slang for those who provide marijuana to friends without keeping score. “I’m in the NFL, and I’m gonna ask people for a few hundred dollars on top of what I paid for it? Nah. Slide me what I got it for and take it. Enjoy it.”

(Larry W. Smith/EPA)

Hurd’s is the voice of a postmodern NFL in which “at least half” of all players, by Hurd’s “conservative estimate,” smoke marijuana at some point during the season, and members of two teams, the Broncos and Seahawks, live and pay taxes in marijuana-legal states. Players smoke (or vaporize) cannabis for various reasons, according to interviews with NFL veterans: to get out of bed easier, to manage stress, to relax, to alleviate pain or simply to get high. Hurd began smoking heavily while rehabbing after ankle surgery in 2008. He never knew a day when his job wasn’t on the line, so once he got healthy again he smoked to reduce stress. But mainly he smoked to get high.

Early in his career Hurd had been entrusted with a secret known by only a few of Dallas’s veterans: Tests for marijuana occurred at roughly the same time each year. Hurd’s main concern was not getting caught as he imported two to 10 pounds at a time from California for himself and for friends, relatives and teammates. As the 2011 NFL lockout dragged on, he thought about flying to Los Angeles to buy a bit more.

On July 1, 2011, Hurd flew from Dallas to L.A. with one of his best friends—former Cowboys safety Patrick Watkins—and a marijuana dealer he’d just met whom we will call Capri. Watkins had blown out his knee while playing for the Chargers in ’10 and was weighing a move to the CFL. (He’s currently a defensive captain for the defending Grey Cup champions, the Toronto Argonauts, and last week was named to the CFL East all-star team.) Capri, for his part, looked like a pro cornerback—shorter than the 6-3 Hurd and 6-5 Watkins, but lean and fit.

The three handsome black men emerged from the Burbank airport, where a friend of Hurd’s, a 27-year-old Armenian-American marijuana broker known as V, picked them up in a white Range Rover and drove them to a home in the San Fernando Valley. Soon, marijuana growers began rolling through the house like Tupperware salesmen, showing V’s wealthy guests some of the finest cannabis the Golden State had to offer. Hurd sampled various strains and negotiated poolside.

One day earlier Hurd had withdrawn $55,000 in cash from two banks in Dallas, most of which he gave to V in exchange for roughly 20 pounds of the best of the best. The order included a couple pounds each of Hurd’s personal favorites: Louis XIII (aka Louie, his daily smoke, which he says allowed him to function and even “practice better and study film better”) and Mr. Nice Guy (a purplish hybrid that Hurd and his teammates found eased the headaches common among NFL players).

Two days after the deal Hurd flew home to Dallas and withdrew another $50,000, right out in the open, just like before. On July 5 he flew back to L.A. with Capri and ordered even more weed. Dozens of text messages between Hurd and V that summer provide a clear window into these events, which would tumble toward late July and the most pivotal days of Hurd’s life.

June 29, 2011

12:51 a.m. Hurd (after receiving a photo from V):What kind is that.

12:57 a.m. V:Louie

July 1

3:47 p.m. Hurd:We get in at 12:15 burbank . . . .

July 3

12:24 a.m. Hurd (upon flying back to Dallas):Made it tell [redacted name] and everyone merci. Great time beautiful can’t wait to c yall again.

12:25 a.m. V:Coool

12:35 a.m. Hurd:Hey tues we there and plz b ready ...

12:36 a.m. V: I got u

On July 13 a U-Haul box weighing 16 pounds was shipped from a North Hollywood address to a house in suburban Dallas where a teammate of Hurd’s had lived when he was with the Cowboys.

July 17

3:20 a.m. V: Did u get the box

July 18

8:25 p.m. Hurd:We good got a box . . . .

But V had even more marijuana to deliver and Hurd needed it yesterday. Word from the players’ union was that the lockout could end any minute. Hurd knew the drug tests administered during training camp weren’t for marijuana, so teammates would be looking to stock up on relaxation for the compressed post-lockout workdays ahead.

July 20

3:04 p.m. Hurd: Yall have to b here by tomorrow and not to late cause I have fb [football] starting up...

At 9:09 a.m. on July 25, police in Denton, Texas, responded to a complaint about marijuana smoke wafting from room 217 of a Courtyard by Marriott hotel. There, officers encountered a sleepy-eyed foursome, including a man with an Eastern European accent who was called V and seemed to be the group’s leader.

When Hurd learned the next morning that V and his friends had been jailed for marijuana possession, he persuaded a reluctant friend to make the half-hour drive from Dallas to Denton and bail them out. Hurd wanted to stay out of the picture, but Denton police had already begun gathering evidence that would place him at the center of it. Extracting data from the Californians’ cellphones, authorities had found incriminating texts sent to and from a phone with a 210 area code.

San Antonio.

Among the findings in the Denton hotel room where V and his friends were busted were cash, cocaine and traces of marijuana.

(Rick Scuteri/Reuters)

One could argue Hurd’s demise had begun in San Antonio, years earlier, in the broken-down Denver Heights section of the Alamo City, where he was born in 1985. But one would have to fight through the voices that insist that Sam was protected by his mother, Gloria Corbin, from the elements that made San Antonio the drive-by-shooting capital of the U.S. during his youth. Ms. Gloria, as neighborhood kids call her, founded the booster club at Brackenridge High and for more than a decade screamed her lungs out at Eagles football games. She remains active in the club today, six years after the youngest of her six children graduated. Current Brackenridge students are surprised to learn the ever-smiling, ever-Jesus-praising Ms. Gloria doesn’t work there.

The worst thing Sam ever did at Brackenridge, according to friends and relatives, was participate in Scuba Squad, soaking classmates with plastic water rifles. When Sam was a 17-year-old freshman at Northern Illinois, he got his first tattoo, an eagle on his right shoulder, to honor the nickname his grandmother had given him when he was a few months old. Bird, she called him, because he was so thin, his neck was so long and his Adam’s apple was so pronounced. Later he had DHT (Denver Heights, Texas) inked on his left shoulder—but he grew to dislike what that represented, so he added a pair of praying hands and Proverbs 3:6 above it in gratitude for having escaped the crime-infested area.

In all your ways acknowledge Him, and He will make your paths straight.

Hurd left NIU with a communications degree, 2,322 receiving yards and 21 touchdowns—the latter two achievements good for second and third place, respectively, on the Huskies’ all-time list. On draft day 2006, while Mario Williams and Reggie Bush went 1-2 to the Texans and Saints, Hurd’s girlfriend, Stacee Green, was applying for the couple’s marriage license in Chicago. Hurd had proposed to her in a cramped room at a local nursing home, kneeling next to the bed of Stacee’s grandmother, who had recently suffered a stroke.

Despite his appealing height and stats, Hurd went unselected in the 2006 draft. The Cowboys signed him the next day. He married Stacee six weeks after that. Then he became the surprise of the Cowboys’ training camp, stretching his rangy NBA body into acrobatic catches that still stand out in coaches’ memories, staying late to run routes and snag balls fired at close range from the Juggs machine, and pestering 32-year-old Terrell Owens for tips on how he’d ascended from unheralded small-school rookie to NFL superstar. Years before Hurd became the Cowboys’ in-house weed connection, his first claim to fame was having impressed coach Bill Parcells by learning all three receiver positions by the third day of his rookie camp. Parcells had never seen that.

When Sam Hurd (17) was sidelined with an ankle injury, the door opened for Miles Austin to emerge. (Christian Petersen/Getty Images)

Hurd’s big opportunity came two years later, in 2008, when Dallas released veteran Terry Glenn and penciled in Sam as a starter. But Hurd wrenched his left ankle in the preseason, rehabbed it and, in his second game back, suffered an even worse high sprain that required surgery. His sutured leg in a boot, he spent the ’08 season and subsequent offseason popping painkillers and wandering listlessly through the life of an NFL player on the PUP list. His starting job lost, he would watch his best friend on the team, Miles Austin, enjoy a breakout ’09 season: 81 catches, 1,320 yards and, soon after, a $54 million contract extension.

The work ethic that had lifted Hurd to the NFL would never lag, but his injuries and the randomness with which players’ fates are decided contributed to a reliance on marijuana that increased when a friend from San Antonio flew in from California, bringing with him a canned energy drink that he cracked open to reveal a plastic bag of ganja—the kind that made what the wild Cowboys of the 1990s smoked seem like yard clippings. Not long afterward, Hurd met V, the guy who had grown that weed.

Hurd spent the summer of 2009 working out, smoking joints the size of his middle finger, playing Call of Duty and chain-watching documentaries on TV, all the while weaning himself off the hydrocodone pills and increasing his weed intake to Marleyan levels. By the time he regained full health, he had fallen out of love with the video games and movies. Only the weed remained.

From then on if one of Hurd’s most trusted teammates visited his house, he might be handed a pungent ziplock bag and notified that it cost $400 or $500—whatever Hurd had paid for it. And if the friend wanted some more down the line, he might put an extra $50 on top every once in a while and joke about “shipping and handling.”

“He wasn’t making any money off players—I know that,” says one Cowboys teammate who spoke about Hurd under condition of anonymity. If a teammate didn’t pay Hurd, which happened a lot, he’d let it slide, although the friend’s chances of receiving more weed would diminish. That is, until he again found his way upstairs to the media room at Hurd’s Irving house, with Wiz Khalifa bumping and everyone taking brain-stinging rips from a Big Chief joint Hurd had rolled as the window ventilating unit tugged their exhalations out into the sky.

* * *

According to Hurd, July 26, 2011—the day he bailed V and his friends out of jail in Denton—was also the day Hurd’s friend Toby approached him with the idea that would eventually lead Sam to that Morton’s steakhouse in Chicago.

Twenty-six-year-old Toby Lujan (loo-HAHN) was a burly former high school safety who managed a Firestone Complete Auto Care shop in north Dallas and had kept Hurd’s cars in shape for about five years. He was the guy who came to the rescue when Stacee’s Escalade got a flat on the way to class at the University of North Texas, or when a taillight on Sam’s 10-year-old Yukon went out. Hurd would give Toby a couple hundred bucks on top of the cost of repairs, plus Cowboys or Mavericks tickets when he had them. He took Toby to church with his family. Their trust in one another evolved, Hurd says, to the point that the two smoked weed together for the first time sometime in June 2011. A month later Toby told Hurd about his cocaine-trafficker cousin, the man called Manuel.

I knew it was illegal, and I knew it probably had to do with drugs. ... Toby didn’t say anything about cocaine, and I didn’t ask.

“Toby said he could make a flip,” Hurd says. “We were in my room upstairs. I had set aside a bag of cash to buy a house for my mother in San Antonio—about $90,000.”

“Toby said that if I let him hold on to 88—exactly 88,000—he would get it back to me in two or three days, plus a little extra for interest,” Hurd continues. “I knew it was illegal, and I knew it probably had to do with drugs. ... Toby didn’t say anything about cocaine, and I didn’t ask. He said the guy in charge was his cousin, and he was, like, this millionaire who had a way of doing his thing without ever getting caught.”

What Hurd knew about Toby made him want to help out. He knew his friend wasn’t making much money at Firestone, and he’d heard Toby say he wanted to pay his father-in-law back for his recent wedding. “Toby wasn’t trying to make a career out of it, either,” Hurd says of the doomed scheme they were about to enter together. “It was just an opportunity he had. I wanted to help him.”

Hurd had already asked Toby to take his Escalade in for a check-up—Sam planned to drive it to San Antonio later that week to buy the house with his mom and make an appearance at the Cowboys’ training camp at the Alamodome, unsigned, to show the team how much he wanted to remain with Dallas. The NFL lockout had ended on July 25, the day V was arrested, forcing teams to cram the months-long process of assembling their rosters into about 72 hours. Hurd figured Toby could make the deal and reimburse him when Hurd got back from San Antonio; no one would ever know about the little loan.

Toby, for his part, would later insist to prosecutors that Hurd was the man behind the deal. Hurd, he says, asked him about buying cocaine, and when he told Hurd about Manuel, Hurd asked Toby to order four or five kilos. Toby’s only job, Toby claimed, was to make the exchange.

* * *

On the morning of July 27, 2011, special agent Robert Alarcon of ICE in Dallas got word from a local informant that a man named Toby Lujan was looking to buy several kilos of cocaine. Alarcon and his partner, Daniel Padilla, weren’t narcotics agents per se. ICE’s mission covers “border control, customs, trade and immigration.” But one of those things is usually involved in drug cases in Texas, so there Alarcon and Padilla were, staking out the spot where they’d been told this deal would go down—a scruffy service road on the shoulder of I-30—and watching a black Escalade approach from the east.

The agents cued a nearby constable to pull Toby over for what would seem to him like a routine traffic stop. Toby’s hands trembled as he produced documents showing the SUV’s insurance was issued to Stacee Hurd. Then the constable spotted something in the back of the Escalade that led him to call over the ICE agents: a canvas bank bag speckled with marijuana flakes, which would turn out to contain stacks of cash.

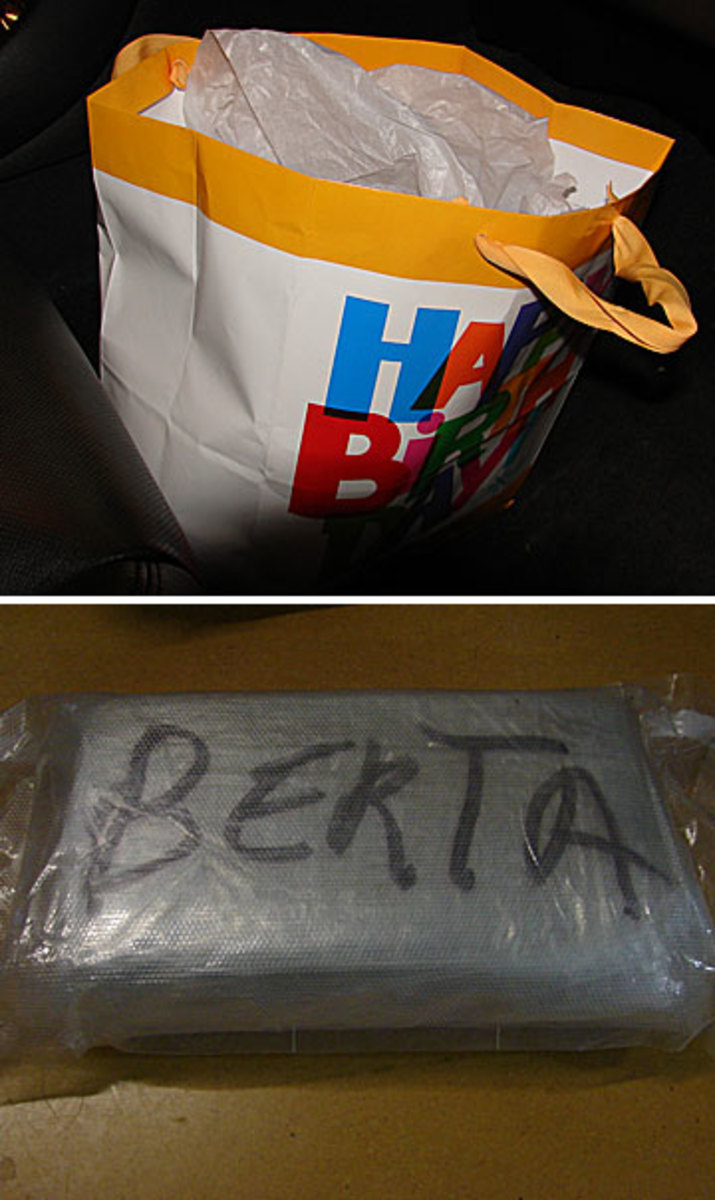

The black Escalade, registered to Stacee Hurd, in which Toby Lujan was pulled over, and the bag of cash police found in the car.

“Lujan stated that the vehicle and all the contents found within belonged to Sam Hurd,” read the agents’ report. “Lujan was adamant that Hurd is a player for the Dallas Cowboys and that Hurd routinely leaves large amounts of currency lying around his vehicles.” The agents downloaded the contents of Toby’s phone, confiscated the $88,000 and allowed him to drive away, vowing to keep an eye and an ear on him. Audio surveillance began the next day.

Toby called Hurd immediately. That afternoon Hurd called agent Padilla, who had given his card to Toby. In his most congenial voice, Hurd left two messages stating that he was Sam Hurd of the Cowboys, that there had been a misunderstanding and that he’d like to see about getting his money back. The following afternoon he drove to the ICE office to meet with the agents in person.

Hurd’s chat with Alarcon and Padilla had barely begun when the player’s agent, Ian Greengross, called to inform him that the Bears had made an attractive offer and that he should fly to Chicago as soon as possible to sign. Hurd hung up and shared this good news with the agents, who remained poker-faced. Hurd looked over their photos and told the agents, Yes, that’s my Escalade, that’s my bag, that’s my money. He said he had put the cash in the bag himself and placed the bag in the Escalade. He told the agents about his mother’s house in San Antonio and showed them a bank statement as evidence that the money had been withdrawn legitimately. But the agents weren’t moved, and Sam had no explanation for the flakes of cannabis on the canvas sack. He left the office empty-handed.

The next morning Hurd flew to Chicago and signed a three-year contract worth $4.15 million, including a $1.35 million signing bonus. The Bears gained a capable third or fourth receiver, an A-plus locker room guy and an eye-popping special teams performer who excelled on all four punt and kickoff units, having made a combined 40 special teams tackles over the previous two seasons.

For his part, Hurd joined a team that had just played in the NFC championship game. In three weeks he and Stacee and their one-year-old daughter would move into a four-bedroom home in Lake Forest, about an hour’s drive from Stacee’s parents, who were eager babysitters, and the same distance from the college campus where Sam and Stacee had met and fallen in love.

PART II

On July 28, 2011, the day after he watched $88,000 of Sam Hurd’s money get lifted from the back of Hurd’s Escalade, placed into a sedan and driven away by the feds, Toby Lujan called Manuel for a postmortem on their botched deal. Their conversation was recorded.

Manuel:Oh, they took the money? ... What your friend said?

Toby:He’s pissed, man. I just gotta figure out how to get it back, man. ...

Manuel:Well, talk to him, tell him to give me a few weeks, let’s wait till the thing cool down ... and then from there, we’ll work. And I’ll tell you how to make me the money back, O.K.

Toby:Yessir. I need that ... I gotta make it up to him.

Two weeks later, special agent Alarcon received a call from a Denton police detective who told him about the four California men who’d recently been arrested in town. Their cellphone data included a 210 number, which had been traced to Hurd. Then there was the matter of the recorded calls the Californians had made from jail on July 26, the day after their arrest. “So, Sam gonna bail y’all out?” one friend asked. “You don’t know Sam’s number?”

Alarcon’s investigation into Hurd had been in a holding pattern since the day the NFL receiver walked sheepishly out of his office. Now it appeared there was more to the innocent-seeming Hurd than Alarcon had thought.

On the same afternoon as Alarcon’s phone call with the Denton police, Manuel rang Toby. The best place to exchange cash for kilos, Toby said, was “nighttime in my shop. There’s nobody f-----g there. Nobody.”

Manuel:How many kilos you want?

Toby:I gotta ask him. . . . Perro [dog], he plays in the NFL.

Manuel (sounding surprised):He play football?

Toby: Sí.

Manuel (excited):You don’t told me that!

* * *

Asked in Seagoville when he felt things turned bad, Hurd answers quickly: “The middle of August.” He was in his room at the Bears’ training camp in Bourbonnais, Ill., nursing a sprained ankle, when Toby called. “He was like, ‘I got this,’ ” Hurd recalls. “He said, ‘It’s my cousin. It’s not a problem. He just needs to hear from you so you can vouch for me in terms of having money.’ ”

Hurd wanted no part of it, he says. Toby was supposed to keep him far away from this. When Hurd flew from Chicago to Dallas on Aug. 31, it was not to meet with Toby’s cousin but to receive the Cowboys’ Ed Block Courage Award—for “professionalism, great strength and dedication”—in front of 2,000 people at the team’s palatial new stadium.

Three weeks of radio silence followed. Then, on Sept. 9, Manuel and Toby discussed a plan to get $50,000 to Manuel and do the deal that weekend at Toby’s garage, after closing. It didn’t happen.

On Sept. 18, Hurd made his regular-season debut for the Bears, in a 30-13 loss to the Saints. Four weeks later, against the Vikings, he had the kind of special teams performance for which he had been signed, tackling return man Percy Harvin inside the 20 on kickoff coverage, returning a kick himself for 24 yards and sprinting downfield with Devin Hester on Hester’s 98-yard kick-return touchdown.

The bank activity and the informant and the phone conversations fell quiet for another two months. Everyone had moved on, it seemed—until the morning of Nov. 7, when Toby got a call hours before the Bears played the Eagles on Monday night, a game Chicago would win 30–24 thanks in part to a fumble recovery by Hurd that set up a touchdown.

Manuel:You guys ready or what? . . . Why you don’t call him?

Toby:I don’t know, perro. S--t, ’cause I still owe him that 88 grand.

Hurd’s Bears were in the midst of a five-game winning streak, but he was smoking marijuana prodigiously. He admits that when he got low on supplies, it was “the only time people saw me get uptight”—as evidenced by several threatening text messages he sent to V in July when he thought the supplier had run off with his money. (In fact V had been arrested.) “And anything less than five pounds was low,” Hurd clarifies.

Hurd was a favorite of fans and teammates. (Nam Y. Huh/AP :: Jeff Gross/Getty Images)

Due to a botched deal that September involving some California kush—this one with Capri, the Dallas dealer who’d accompanied him to California over the summer—Hurd lost nearly $20,000. Suddenly the $88,000 Toby had lost became a bit more important to him. Hurd was more than 100 large in the hole.

On Dec. 5, one day after the Bears were upset by the lowly Chiefs, Toby got a call from Manuel. “I want you to make some money, vato,” Manuel said, “but what happened with your friends?”

Toby suggested that Manuel come meet him at his shop the next day; there he would put Manuel and Hurd on the phone together. “That way you can get to know him a little better, vato,” Toby said.

For the eavesdropping ICE agents, the prospect of Hurd emerging from the background and establishing himself as the money behind Toby’s cocaine deal was more than enough for them to set up their microphones and cameras at Firestone Auto Care the next afternoon.

* * *

At 3:35 p.m. on Tuesday, Dec. 6, Manuel rolled up to the Firestone shop in his Mustang convertible. Toby emerged from the garage. They embraced, climbed into Toby’s Tahoe and closed the doors as Alarcon and Padilla listened from a car parked nearby.

“Perro, I just called him now and he said he wanted to talk to you,” Toby said before dialing. “This is Sam. ... Nobody can know [it’s] him, perro, because he plays for the f--king Chicago Bears, cabrón.”

Manuel said he didn’t care: “I’m a businessman.”

“Hey, kinfolk, what’s up baby?” Toby said into his phone to Hurd. “You got a minute? Let me let you talk to my boss real quick.”

“Hello,” Manuel said into Toby’s phone. “What’s up, man? This is Manuel.”

ICE’s microphone faltered over the next minute or so, but Hurd could clearly be heard saying: “Whenever y’all are ready ... my boys are coming down to help me down there this weekend. They’ll be down this weekend to try to grab two or three of ’em.”

Manuel asked how many kilos he wanted: “Why you don’t get me five? You don’t got enough money for the five?” Manuel offered to front a kilo to Hurd—to lend it to him with the understanding of later payment—to help him earn back what he’d lost in July. “Little by little, I wanna help you,” Manuel said.

“I thank you for that, too,” Hurd said. The conversation ended with a vague agreement to exchange cash for kilos sometime that weekend after Toby closed his shop.

Six minutes later Toby told Manuel, “Perro, he makes f--king $4 million a year, vato. ... That’s how much the Bears pay him—$4 milliona year. So, vida, he’s got plenty of f--king money, bro. ... Last year I made, like, $38,000 ... that’s why I need money for, to pay for the f--king pinche wedding and all that s--t. Anyway, but I promise, bro: This guy, he’s gonna do it, bro.”

Two days later—six days before they would dine together at Morton’s—Manuel called Hurd directly. Manuel said that his incoming cocaine shipment was spoken for. “That belong to the Zetas; we work with the Zetas, O.K.?” he said. (“I had no idea what Zetas was,” Sam would say later, in Seagoville.)

Hurd:O.K., no problem. ... I was gonna tell you that next week would be best, so I can get all five. Or maybe even 10.

Manuel:O.K., and I wanna ask you something. We wanna meet with you, you got time—

Hurd:No problem. You can come to a game.

Manuel:Because we need to talk about the quantity you can sell a week. ... We don’t wanna do one-time deal and then—

Hurd:Not at all.

Manuel:We want a ...

Hurd:Relationship. ... I’m with you. I wanna deal. Relationships—that’s what it’s about.

Manuel:O.K., let me have a conversation with my cousin and I’ll call you back.

Hurd:O.K., then.

The next day, Dec. 9, the Bears flew to Denver, where they suffered the third loss in what would be a five-game losing streak that booted them from playoff contention. Two days after the Broncos game Hurd was back in Chicago, returning a call from Manuel.

Manuel:Meet tomorrow, right?

Hurd:Yep, tomorrow night for sure.

Alarcon and Padilla boarded a plane for Chicago.

(Matt Strasen/US Presswire)

That summer, when Toby had first told Hurd about Manuel, he had described him as a seasoned pro who would never get caught. That much was true. There was no chance Manuel would be arrested, because Manuel was an informant—the informant who had lured Toby into the $88,000 cash seizure, a government operative whose real name and whereabouts remain closely guarded secrets. One of the few things known about Manuel is that he is not Toby’s cousin; that was just a term of affection between the men.

Manuel almost certainly had not expected that the deal he told Alarcon about back in July would involve an NFL player, or that he himself would fly to Chicago with an undercover agent impersonating his nonexistent cousin Juan. But there Manuel was, splashing through Chicago in an SUV driven by Juan, who stopped a block west of Morton’s so a local ICE agent could give him the white HAPPY BIRTHDAY gift bag. At the bottom of the bag, beneath the crumpled squares of decorative tissue paper, lay a brick-sized kilo of cocaine bound in shiny plastic wrap.

Setting up in and around the restaurant that night were 22 law-enforcement officers, including Alarcon and Padilla. The body wires on Manuel and Juan would pick up Hurd’s voice poorly over the next 77 minutes, but Hurd provided plenty of evidence to support the agents’ contention that he was there with the intention of setting up a long-term cocaine-trafficking network.

Hurd would later contend that he was merely impersonating a guy setting up such a relationship, so that Toby would look financially supported. Hurd would have stepped away after this meeting, he said, and let Toby do his deal, earning back that $88,000.

It isn’t an explanation to be proud of, Hurd concedes, and he knows it still makes him guilty of conspiring to traffic cocaine—“which I am willing to be sentenced fairly for: my role in that entire Toby thing,” he says—but there is reason to believe he is telling the truth. “If some sort of windfall had come to me as a result of that [Morton’s] meeting, I’m not going to tell you I would have turned it down,” he admits. “I’ve got nothing to hide anymore.”

Manuel and Juan, who Sam Hurd thought were traffickers but who were working a sting, brought a birthday bag containing a kilo of cocaine to the Morton’s dinner to snag Hurd.

The moment of truth arrived roughly 15 minutes into the Morton’s meeting, when Juan asked Manuel in Spanish, “¿Ha tocado la cosa él?” (Has he touched the thing?)

Manuel:No.

Juan (to Hurd):When they give you a key [kilo], if it’s a little loose, you know it’s been cut, right?

Hurd:Oh, for sure . . . .

Juan:Our s--t is, like I tell you—it’s good stuff ... Since it’s my birthday, I got a little something in there, if you wanna just check it really quick. And you can see ... what you’re gonna be getting. I mean, you’ll see what you got.

The paper bag crinkled over the murmur of other diners as Hurd felt the outside of it.

Juan:You can feel the difference. You can tell right away.

Hurd:Oh, 100 percent.

Juan wanted Hurd to take the bag with him when he left, but not for free. In order for the feds to make their case, there had to be a transaction, or the promise of one, so Juan said, “If you want, you can take that. ... We’ll collect later on.”

“O.K.,” Hurd promised. “Tomorrow or the next day after that.”

By then the conversation had become less a drug deal than three guys just talking. Hurd’s tone was jovial and joking throughout the dinner. He made the two other men laugh. He cut through months of NFL media babble when asked about the 0–13 Colts and the inactive Peyton Manning: “When you build an offense around one person, without that person it don’t run that smooth.” After they ordered dinner Hurd asked an unexpected question: “Can you get, like, mid-grade regular weed?”

Juan answered, “¿Qué?” Then, seizing the opportunity: “How many pounds of weed do you want?”

“I’ll be fine with 1,000,” Hurd said.

The amazement in the undercover agent’s voice was unmistakable: “A week?”

“Five hundred at the least, you know. Probably be a lot higher.”

After a few more starts and stops in their conversation, Juan asked his informant, “¿Listo?” Ready?

Manuel:Listo.

The gift bag crinkled as it was picked up—by whom is not clear from the video. Hurd later said he accepted the bag reluctantly when Manuel handed it to him with the parting words, “Happy birthday.” (This line is audible in the recording but does not appear in the investigators’ 105-page transcript.) The agents insist Hurd picked up the bag himself.

Juan:Mucho gusto.

Hurd: Mucho gusto.

“I was scared, first of all,” Hurd says in answer to the question that would scratch at the minds of his friends, fans, teammates and relatives: Why did he walk out of there with that kilo? “I thought these were real cartel dudes, and I was there by myself. I didn’t have nobody with me. No gun—nothing. I thought giving somebody a kilo like that was what they normally did. I didn’t want to disrespect them.”

As it turned out, the investigators didn’t need perfect audio, because the most important evidence was captured at 9:08 p.m. with a video camera being operated by a Chicago police officer sitting inside a parked car: HD footage of Sam Hurd walking out of Morton’s with that sack of cocaine dangling from his hand. He spat on the street as he strode toward his Escalade.

Asked in Seagoville what he had planned to do with the kilo, Hurd replies, “Call Toby and ask him, Now what?” It was a moot point, though, because as soon as he closed the door of his Escalade, placed the bag on the passenger floorboard and raised his head again, there were headlights speeding at him, two cops seeming to leap out of them.

Forty-five minutes later Alarcon and Padilla walked into the interview room at Homeland Security Investigations’ Chicago field office, where Hurd was waiting. He hadn’t seen the agents since July, when he showed up at their office asking for his $88,000.

Nothing new was revealed during the 12-minute consensual interview, other than that Hurd still believed Juan and Manuel were cartel-affiliated cocaine traffickers. He stopped the interview when he was asked about the men he’d dined with: “That’s where I—-explaining, talking about others, ya know ... Let me wait ’til my lawyer talks, tells me what to say.”

The agents told Hurd politely that he would spend a night or two in jail before his first hearing. “Are there any other questions?” Padilla asked.

“When do I call my wife?” Hurd whispered.

As bleak and as confounding as things seemed, however, the most troubling chapter in Sam Hurd’s demise had yet to unfold.

Hurd speaking to youth at his annual football camp in 2009. (Edward A. Ornelas/ZumaPress.com)

PART III

Willie Hall has coached football at Brackenridge High for 31 years. A leather-tough Billy Dee Williams look-alike whose insistence on hard work and integrity has led two generations of parents to push their sons toward his fall tryouts, Hall put a five-foot-tall action photo of Sam Hurd as a Cowboy outside his gymnasium when Hurd made the Dallas roster in 2006. Despite recent pressure to remove it, the photo remains. “It’s not going anywhere,” Hall says in a voice raspy from an overtime win the night before.

“What happened? Who pulled [Sam] into this, and how did he let them?” asks Paulette Gayer, whose 11-year-old son, Mick, is playing with his younger brother in the spacious yard outside their spacious home in suburban San Antonio. “I watched him crouch down to [Mick’s] level and connect with my son at a time when he was struggling to connect with anyone.” That meeting took place in 2009, at Hurd’s annual football camp for autistic children, where Gayer’s mind was changed about what a 24-year-old pro football player could be. “It’s clear he has a gift,” Gayer says.

“I believe in our justice system,” says Rene Capistran, a former United Way board member who invited Hurd to host a camp in the sweltering border town of Brownsville that earned Hurd zero dollars despite its high attendance. “But this is not the same guy. Sam bowed his head and prayed before every meal, after every practice. He never said a profanity. He and I have played more than one round of golf together—we’re both terrible, so we have that in common—and I never heard a negative word come out of the guy’s mouth. ... I can’t even get to the point of imagining a theory of what happened here.”

The most visceral reaction to Hurd’s arrest was probably the one that took place on Dec. 15 at Toby Lujan’s Firestone shop. Toby was preparing the register when a friend called and asked, “Are you watching ESPN?” Toby clicked over and crumpled to his knees in panic. He drove home and, according to his lawyer, cried, knowing that his own arrest was imminent.

Toby Lujan.

The Bears released Hurd the next day, Dec. 16. He and Toby were indicted on Jan. 4, 2012. The only conversation Hurd says he’s had with the prosecution since then came a week or so later, when Assistant U.S. Attorney John Kull called him. “He said, ‘Toby’s coming in here in a couple weeks,’ ” Hurd recalls. “ ‘The way it works is, whoever comes in first gets the best deal.’ And when he said goodbye he was like, ‘Remember: Toby’s coming in soon.’ ”

Toby came in on Jan. 27, taking a seat in the Dallas U.S. Attorney’s office with his lawyer, ICE agents Alarcon and Padilla, a Denton detective, Kull and fellow Assistant U.S. Attorney Gary Tromblay. Toby claimed Hurd and Manuel knew each other before the failed $88,000 deal and that Manuel had called that morning in July asking for Hurd. After the agents told Toby that those statements were “inaccurate,” he clarified “that he, Lujan, was the person who coordinated the deal,” according to the ICE report. But Toby insisted that Hurd was the guy behind the whole thing; it was Hurd who asked him about a cocaine source and Hurd who put up the money. (Toby, who declined to comment, is scheduled to be sentenced on Jan. 8, 2014.)

Toby was released from jail and ordered to stay in Texas. Hurd was released in Chicago on $100,000 bond, and his court supervision was transferred to San Antonio, where he moved in with his sister Jawanda and her husband and children in their new home in a woodsy subdivision.

Jawanda—a polished, board-certified behavior analyst—runs a company in San Antonio that helps autistic children and their families. It had once been an annual rite for her to drive several of “her kids” to the camp that Sam held for them each summer. Now Sam’s wife and child were living with him in a spare room at Jawanda’s house while the family waited for this whole cocaine misunderstanding to get sorted out.

Hurd had no idea how that might happen, but as he waited for his lawyers to set matters straight, he volunteered at the local food bank and played in a flag football league with some high school friends. The court required him to remain gainfully employed while he awaited trial, so he worked in the billing department of Jawanda’s company, which meant that he plopped down on her couch with a laptop and headset and processed a stack of medical bills, saying things to insurance company reps like, Why was the claim denied? and I show no record of that.

He was still smoking weed, despite the court’s order that he refrain. That violation would prove to be small potatoes, however, because, if you believe the federal government, Hurd was also conspiring—again—to buy kilos of cocaine.

Hurd recalls June 6, 2012, as a normal day. He checked in with his P.O., did a little work for Jawanda, went to the YMCA to swim. Phone records show that he made and received several phone calls that afternoon; the most important one, at 3:10, was from his cousin Tyrone Chavful (pronounced Shaffle) just as Hurd was leaving the Y.

Tyrone was a 45-year-old convicted marijuana trafficker who ran a struggling T-shirt shop in Denver Heights called T-Love Express. T-Love had been his handle when he was large in the marijuana game, back when he moved half-ton loads through San Antonio and Austin, raking in enough money to buy a couple of Jet Skis and a loaded Ford Expedition. Tyrone had done time for moving weed, spending most of the eight years between Hurd’s senior year of high school and his fourth year in the NFL in either state or federal prison.

According to Hurd and several others around Denver Heights, Sam barely knew his cousin. Hurd says that the only meaningful contact he had with Tyrone—aside from lifting their chins toward each other at a grandparent’s funeral—was when Chavful loaned his Expedition to Hurd on prom night. Hurd returned it with a small ding, but Tyrone was cool about it.

Hurd also recalls that Tyrone was out of prison during Thanksgiving break one year when Hurd was still at NIU. Tyrone gave him two pounds of weed to take back to school. “He said it was Lime Green [hydroponic marijuana],” Hurd says, “but it ended up being [inferior] Mexico Brown.” Still, it was better than anything in DeKalb, Ill., so Hurd and his teammates hoarded and smoked it contentedly.

In the late spring of 2012, while Hurd was out on bond in San Antonio, Tyrone—still on supervised release following his most recent prison stint—was toiling at the T-shirt shop while trying to get back in the weed game. At 3:04 p.m. on June 6 he got a call from a longtime marijuana trafficking associate, a Mexican cartel guy who told Tyrone that he was headed his way with the big load Chavful had recently ordered. When Tyrone hung up he called Hurd three times—at 3:05, 3:06 and 3:10.

Phone records show that Hurd didn’t answer the first two calls, but he picked up the one at 3:10 and had a 40-second conversation with his cousin. A few minutes later, Tyrone Chavful was arrested. His trafficking friend had turned informant, and the truckers who backed their rig up to Tyrone’s T-shirt shop were actually federal agents. They slapped handcuffs on Tyrone as soon as their five kilos of cocaine and 200 pounds of marijuana were unloaded.

Chavful had felonies on his record that stood to add years to the lengthy prison sentence he was now facing. After his arrest he learned the DEA had placed three informants on him the previous fall—all cartel guys, previous weed connections of his, including the man who set him up on June 6. The phone calls recorded by these informants, who had trafficked tons of marijuana with him over the years, reveal that they had been coached to ask Tyrone about his “cousin who plays football.”

The case laid out by investigators suggests they gave little credence to the possibility Tyrone had played along with these hints and pretended Hurd was his partner because he needed the clout of an NFL salary behind him. It also appears they gave little consideration to the fact that Tyrone owed the DEA’s main informant $300,000 from a deal that had taken place years earlier. Which meant he had no chance of getting any product fronted to him unless he had the financial backing of, say, a wealthy cousin who played in the NFL.

Moreover, any link between Tyrone and Hurd would appear tenuous in light of a call Chavful made to a DEA informant two days after Hurd was arrested in Chicago. After Tyrone delivered the news he admitted, with a touch of embarrassment, “I didn’t know nothing about it.” Hurd himself seemed to dissolve the link during the dinner at Morton’s. On a night when he repeatedly tried to sound connected, Hurd reversed field when it came to Tyrone, telling Manuel and Juan, “My cousin and them, everybody is connected to some part of the cartels ... but I don’t f--k with him like that.”

Another important detail: When the DEA informant called Tyrone on June 6 to tell him his truckload of dope was on its way, he asked Chavful if he had the money to pay for it: “You gonna have that ready for the driver? ... At least something, that way he doesn’t get mad.” It’s rule No. 1 in the game: Unless there is some other arrangement, all deliveries are COD. Tyrone didn’t have some other arrangement. He needed money.

Tyrone Chavful.

Hurd answered Tyrone’s third call at 3:10 p.m. The government would later contend this was Hurd speaking with his drug-trafficking partner about their incoming haul of cocaine and weed. Sam Hurd has no response for this other than to plop his forehead into his hands, his broad grin belying the seriousness of the matter. “Was he calling me to ask me for money? Probably,” Hurd says. “He probably thought I was big in the game because of what happened at Morton’s, just like everyone else thought, and he figured I could help him out of the spot he was in. But to say that I was moving pounds of weed and kilos of cocaine with a guy who had already been caught a bunch of times—while I was under indictment on this big cocaine case that had just ended my career—I mean, it’s crazy.”

At Hurd’s detention hearing, his lawyer Jay Ethington gave one explanation as to why Tyrone might have told Alarcon and Padilla that Sam Hurd was his drug partner. “[Tyrone is] a convicted felon,” Ethington said. “He’s been in prison, he’s been released, and he’s pretty savvy of the system I would guess. He’s trying to benefit himself, and that’s it.”

By that time Tyrone had also told agents Hurd had bought 30 pounds of marijuana from him the previous month by paying $10,500 in cash, carrying the load out of the T-shirt shop in a big blue Igloo freezer and loading it into Jawanda’s black Mercedes. The corroboration ICE provided in court documents—a drug test he failed around that time—is not conclusive. Yet all of these heaping drug quantities have been factored into Hurd’s proposed life sentence. (Meanwhile, Hurd’s defense team filed a brief with the court containing phone records suggesting that the buyer Tyrone was dealing with was not, in fact, Hurd, but a relative of a different NFL player—a man who lived in central Texas at the time and has a history of drug crimes.)

As if things weren’t bad enough for Hurd already, two weeks after Tyrone’s arrest in San Antonio, Capri, the weed dealer who had flown with Hurd to California back in July 2011, was arrested by Texas DEA agents on a cocaine trafficking charge unrelated to Hurd. Capri did not wait three weeks to talk to the ICE agents about Hurd, as Toby Lujan had. He didn’t wait seven weeks, the amount of time Tyrone held out before he began cooperating. Capri sat down with special agent Padilla on the very night of his arrest.

According to Padilla’s report of that interview, as soon as he entered the interview room and introduced himself, “[Capri] stated ‘Sam Hurd’ and advised agents that he had information regarding Hurd.” This from the man who, according to one of Hurd’s Dallas teammates, had walked up to a Cowboys player in a Dallas restaurant 10 days earlier and told him that Sam’s cousin Tyrone had just been arrested, that Sam was about to feel some more heat, and that “if Sam ever mentioned [Capri’s] name to the police, he would go after Sam and his mom.” (Capri confirmed to Sports Illustrated that he approached this player but denies making a threat.)

Unlike Hurd, whose only prior was a misdemeanor battery charge (deferred adjudication) for a fight at a party in college, Capri knew the system. Like Tyrone, Capri had faced felonies before, including convictions for harassment and weapons possession. And like Tyrone, he made statements to ICE that would be factored into the recommendation that Hurd be sentenced to life—with the same inadequate corroboration. He told ICE agents that he’d watched Hurd snort cocaine at V’s house in California and that he saw white powder under Sam’s nose on another occasion at Hurd’s house. In Capri’s second conversation with the agents, 10 days after the first, he said that Hurd had asked him for a cocaine connection when they first met.

Capri’s allegations would come as a shock to three eyewitnesses to the moments he had described. V, whose given name is Vazgen Galadjian, and former Cowboys players Patrick Watkins and Quincy Butler each told Sports Illustrated, independent of one another, that they never saw cocaine around Sam Hurd, that they never heard cocaine discussed around him, and that they never heard Sam even say the word cocaine.

(Rex Brown/Getty Images)

These three witnesses could be protecting their friend, Hurd, but if so, they are also knowingly defending a convicted cocaine trafficker who talked like Tony Montana inside that Chicago steak house and walked out carrying a kilo. More relevant than their frustration with Capri’s claims is their confusion over the government’s failure to contact them to corroborate Capri’s story, which he shared with ICE more than a year ago. (“What they are letting this guy do to Sam is unbelievable,” says Butler, who regrets introducing Capri to Hurd in the spring of 2011.) Capri gave the agents the names of the three witnesses, but Galadjian, Watkins and Butler say they have yet to receive a phone call or a visit from the authorities.

The same goes for Sammal Hurd, Sam’s younger brother, who is described in Tyrone’s and Capri’s accounts (as well as in Toby Lujan’s) as Sam’s drug-dealing accomplice but who hasn’t been charged or questioned in his brother’s case. “I haven’t heard nothing from nobody,” says Sammal, who proclaims his innocence of anything more than the marijuana misdemeanor charges he has incurred around San Antonio. “I haven’t changed my [phone] number, either. They got my number if they want to call.”

During a recent phone call from the Texas prison where he is being held, SI asked Capri whether Sam Hurd had spoken to anyone about cocaine during their two trips to California. He replied, “I can’t tell you that. I don’t know. I don’t know about that one.”

Was Hurd involved in the cocaine business? “He’s indicted for it. That speaks for itself. ... I never seen him do any transactions with cocaine.”

Did you witness Sam conducting cocaine business in California? “Nah, I haven’t seen that. I won’t lie about that. I haven’t seen that.”

And yet the cocaine quantities Capri has attributed to Hurd during conversations with the government have been used to justify Sam’s proposed life sentence.

Sentence me for what I did. Moving weed and getting caught up in this stupid cocaine thing with Toby—I am ready and eager to be sentenced fairly for those things. ... All this other stuff, though ...

On Aug. 12, almost exactly a year after Hurd was arrested in San Antonio for his alleged role in Tyrone Chavful’s drug dealing, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder took a stand against the way drug defendants are prosecuted and sentenced, telling an American Bar Association conference in San Francisco: “As the so-called war on drugs enters its fifth decade, we need to ask whether it, and the approaches that comprise it, have been truly effective.” The nation’s chief law-enforcement officer made it clear that his answer to that question was no, vowing “that certain low-level, nonviolent drug offenders who have no ties to large-scale organizations, gangs or cartels will no longer be charged with offenses that impose draconian mandatory minimum sentences.” Holder was some 1,500 miles away from San Antonio, but he might as well have been speaking directly to those who had conducted the Sam Hurd investigation or calculated the sentencing recommendation that resulted from it.

When Alarcon took the stand at Hurd’s detention hearing on Aug. 28, 2012, and was asked to provide evidence of Hurd’s participation in Tyrone’s drug dealing, he leaned heavily on the calls Chavful made to Hurd on the afternoon of Chavful’s arrest. Eventually Alarcon expressed his own doubts that Hurd and Tyrone had worked together; he testified that over the previous seven months (a span that covered the entire Chavful investigation), “I didn’t suspect that Mr. Hurd was involved in any narcotics trafficking.”

That didn’t stop U.S. Magistrate judge Jeff Kaplan from revoking Hurd’s bond and sending him to Seagoville “pending the disposition of this case.”

After the hearing “Hurd turned toward his family and supporters in the courtroom and said, ‘Lies,’ ” the Associated Press reported.

“Sentence me for what I did,” Hurd says. “Moving weed and getting caught up in this stupid cocaine thing with Toby—I am ready and eager to be sentenced fairly for those things. They have hurt my family and they will continue to hurt us. All this other stuff, though. . . . Don’t you think if I really did that, I would have confessed and gotten my sentence knocked down as soon as they started talking about life in prison?”

* * *

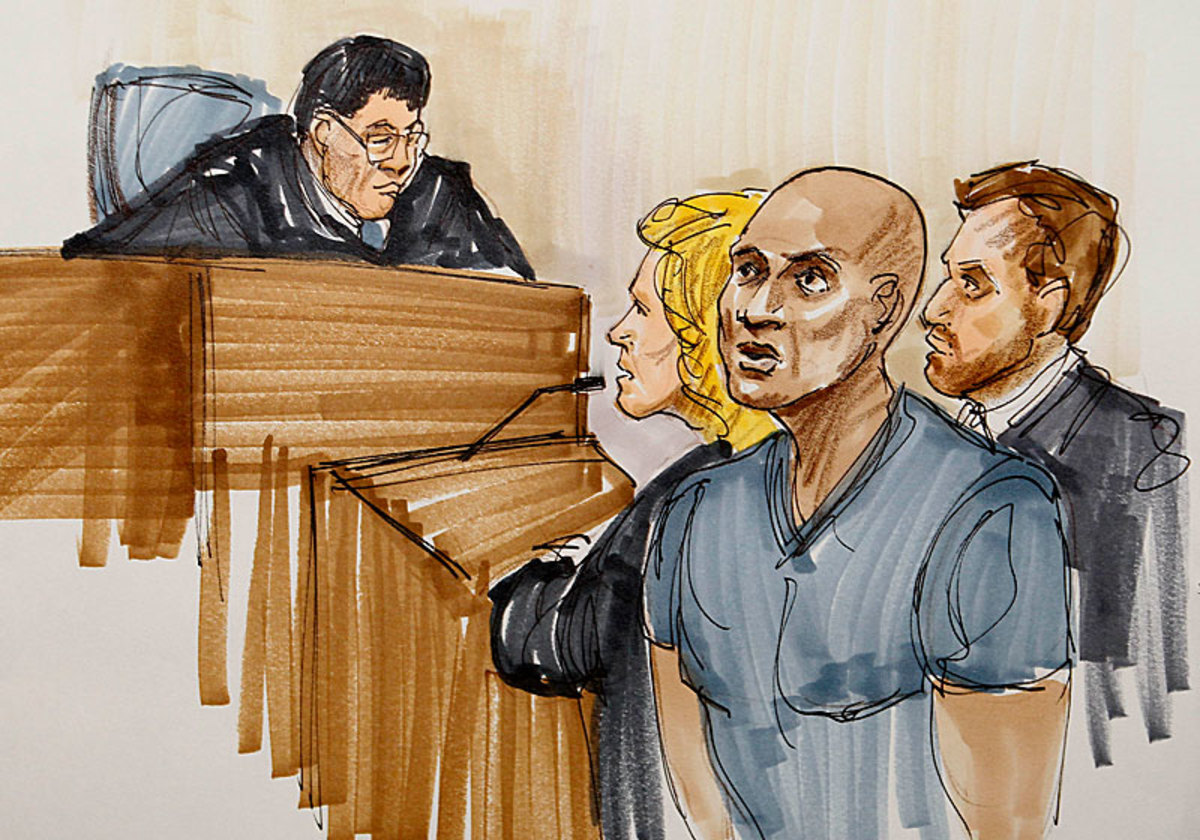

A courtroom artist’s drawing of Hurd’s initial appearance on federal drug charges in December 2011 in Chicago. (Tom Gianni/AP)

After a two-and-half-year odyssey, the disposition that Judge Kaplan spoke of is upon us: Hurd’s sentencing hearing is scheduled for Wednesday, Nov. 13. The guilty plea entered by Hurd’s lead counsel, Michael McCrum, will allow him to contest Tyrone’s and Capri’s allegations at that hearing, but McCrum admits that his work is cut out for him. Sentencing recommendations such as the one affixed to Hurd hold great weight with federal judges, and the prevailing expectation is that U.S. District Court judge Jorge Solis will sentence Hurd to life.

The final bricks in that wall were added during Capri’s third and fourth meetings with the government, in March, during which he said Hurd had introduced him to Hurd’s cocaine supplier in California—a guy named Carlos—when Capri and Hurd were out there and that Hurd had ordered 10 kilos of cocaine as well as more than a ton of marijuana. According to Capri, Hurd also claimed to have dealt cocaine as a college player at Northern Illinois. Capri had not made these claims in his earlier conversations with the government, the report said, “due to the fact that he had recently been arrested for a cocaine deal and wanted to distance himself from anything having to do with cocaine.”

The last of the government’s meetings with Capri took place on March 28, 2013. Coincidentally, that day was the 18th anniversary of former Los Angeles Rams cornerback Darryl Henley’s conviction on cocaine-trafficking charges in L.A. Hurd had been told that Henley was locked up in Seagoville, but he knew nothing about Henley or his case. He didn’t know that Henley, while convicted of many crimes—including some in which his guilt is not clear-cut—had also seen the way the dynamic of a case can change when the suspect is an NFL player.

This summer, when Hurd was moved to Seagoville’s fetid Segregated Housing Unit as part of the rotation that kept him away from Tyrone and Capri (who were also housed in Seagoville), a rumor came down the corridor that moved Hurd to whisper toward the next cell, to a man he couldn’t see, “You D. Henley?”

“I am. You Hurd?”

It does me no good to hold ill will toward [Toby, Capri and Tyrone]. Am I comfortable with the idea of going away for life? Of course not. I think about it all the time. But it does me and my family no good if I go around mean-mugging people or trying to get vengeance. I pray for those guys.

What followed was a tragic serendipity, a conversation between a pro wideout and cornerback imprisoned next to each other for moving large quantities of hard drugs while they were active in the NFL. They talked about their cases, the “friends” they were too weak and too blind to resist, the numerous chances they had to bail out of their doomed schemes before the harsh end came. (Henley’s end arrived when a Rams cheerleader was caught at the Atlanta airport in 1993 with 12 kilos of cocaine.) And they marveled sadly at the similar paths, 18 years apart, that led them to the hole beneath a prison in north Texas, boiling in their 110-degree cells, lying on the concrete floor for a scant few degrees’ relief.

Hurd says he has forgiven Toby, Capri and Tyrone (who last month was sentenced to eight years in prison): “It does me no good to hold ill will toward them. Am I comfortable with the idea of going away for life? Of course not. I think about it all the time. But it does me and my family no good if I go around mean-mugging people or trying to get vengeance or any of that. I pray for those guys. My mom told me to pray for those prosecutors too, like she does. So I do that also. I am in prayer mode and fighting mode now.”

Meanwhile, back at Brackenridge High, Willie Hall, the graying football coach, asks, “Where’s the money? If Sam is this big kingpin who’s moving kilos here and there, where is the money to support all that? It wasn’t in his bank accounts. The government searched his house. Before you talk about life in prison, tell me where that money is.”

Until he gets an answer, Hall says he will keep the big photo of the convicted cocaine trafficker on the wall outside his gym, so that if nothing else his kids might learn something about “how the criminal justice system in this country really works.”

At Seagoville, Hurd has learned firsthand about the Zetas, from one of the leaders of that cartel, who laughed at the idea of a real Zeta trafficker giving a kilo to a potential client in a crowded restaurant. And he has watched inmates laugh at his naivete. “You don’t just barge into the game talking about moving big numbers right off the bat,” Hurd says he was told. “That’s something you don’t get your leg broken for. That’s when you come up missing.”

He has also heard Henley warn him about being too loud and too friendly with too many inmates. “The thing I worry about with Sam is how talkative he is with people in here,” says Henley. “He’s not very discreet at all with what he shares or how loud he shares it. And he’s not even on the main line [in an actual federal prison] yet. That can be more dangerous than he knows.”

(Sharon Ellman/AP)