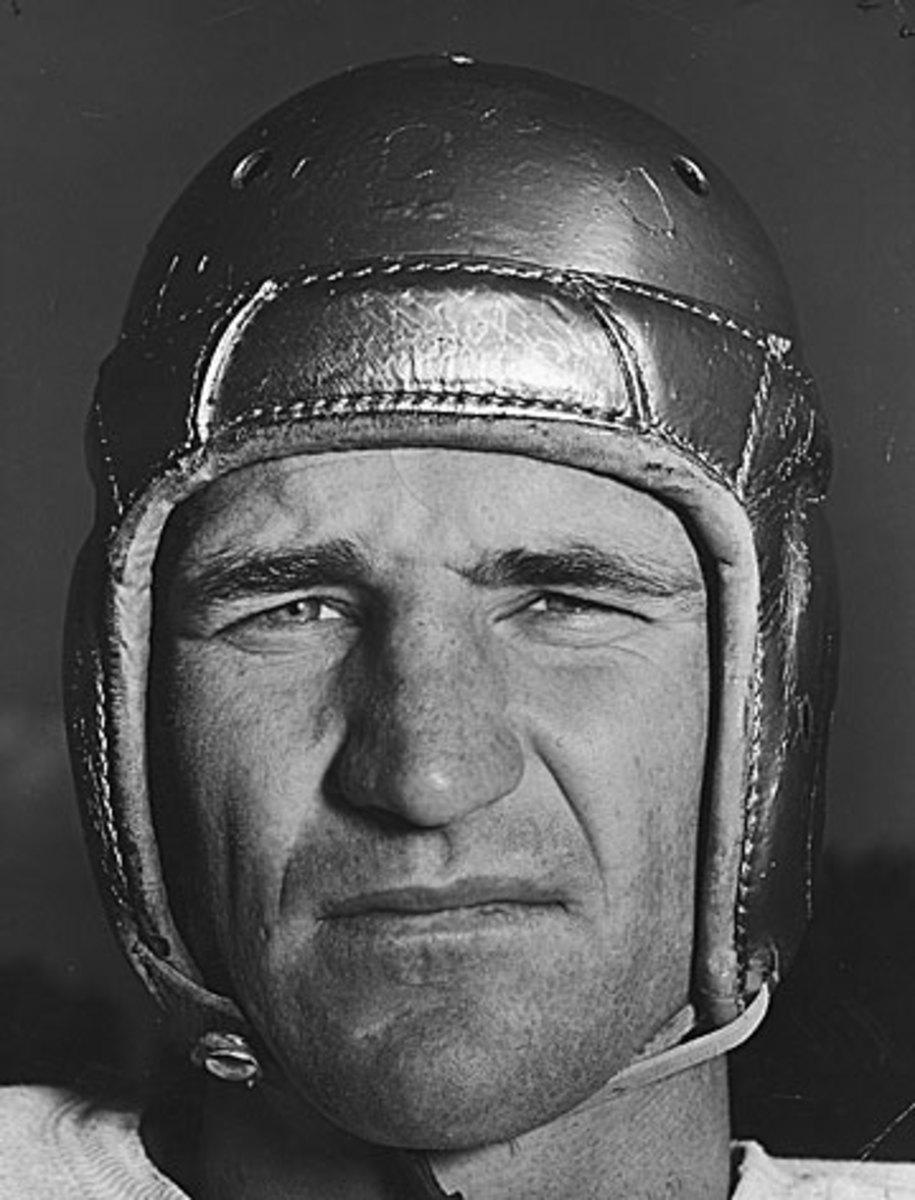

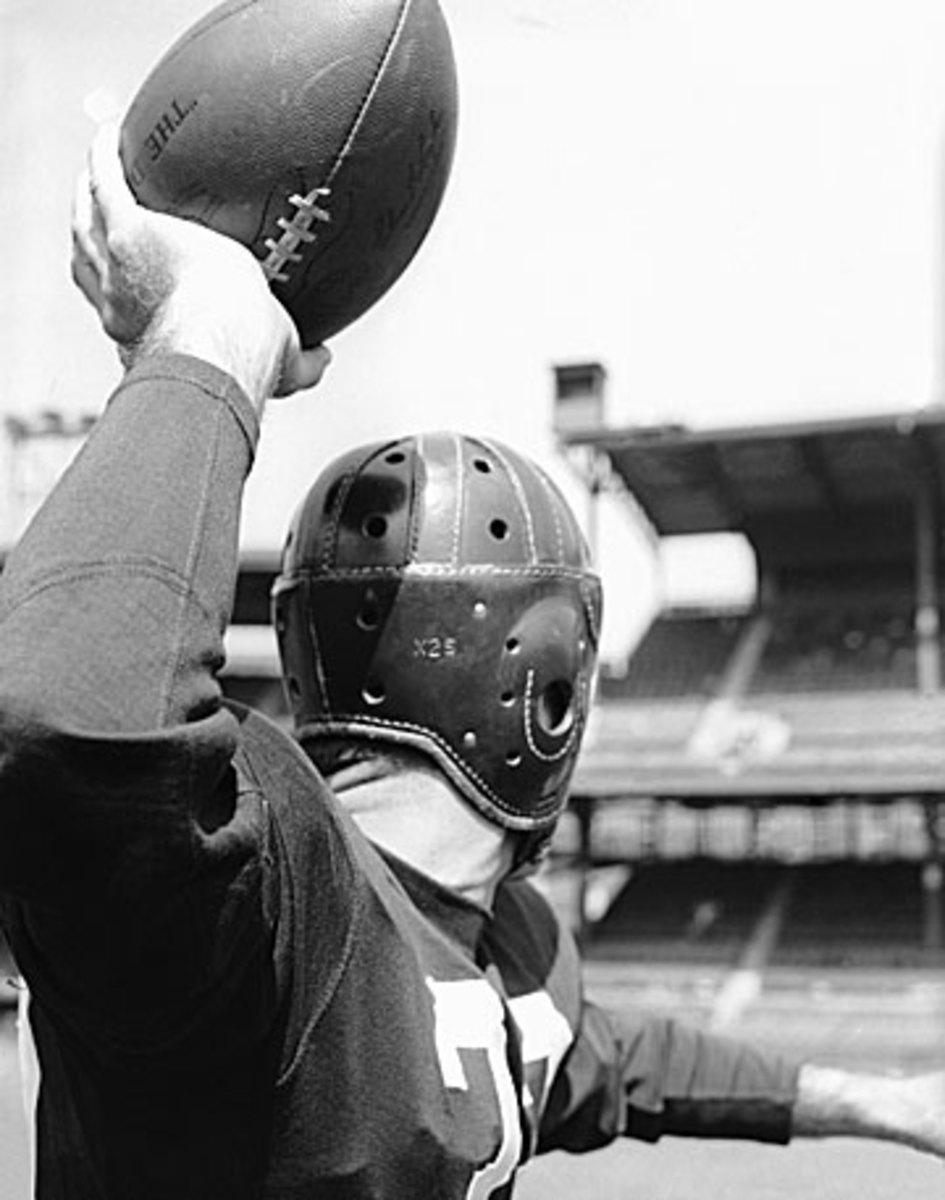

Sammy Baugh, 1943: The Greatest Season?

By Dan Daly

WASHINGTON — He had the arm of a god . . . and the legs of a flamingo. Sammy Baugh could throw a football through the earhole of a helmet, or near about, but when he peeled off his pads, his unglamorous gams visible to all, a teammate would be sure to say, “You’re not going to go downtown on those legs, are you?”

Baugh, the Washington Redskins legend, was an unusual physical type, even in the NFL’s pre-Muscle Beach days. He looked more like a receiver, if you wanted to be charitable, like somebody who might be nicknamed Bones. But the things he could make his 6-foot-2, 182-pound body do. Like pass. And punt. And snatch interceptions out of the air. Heck, simply surviving 16 seasons—a record at the time—in the ruthless, toothless leather-helmet era was a testament to his genetic freakishness.

Seventy years ago, those legs took Baugh to places never seen before or since. If it wasn’t the greatest individual season in pro football history, it’s definitely among the finalists. In guiding the Redskins to the 1943 championship game, Slingin’ Sam did just about everything a player can do—on offense, defense, even special teams. Of course, they didn’t call them “special teams” back then. They just called it “playin’ football.”

(Carl M. Mydans/Time Life Pictures)

Some of Baugh’s more notable accomplishments that year, just to get us started:

● As the tailback in Washington’s single wing, he completed 55.6 percent of his passes, best in the NFL that year. That might not be up to Drew Brees’s standard, but the rest of the league’s passers in ’43 completed a collective 42.6 percent of their throws.

● He threw 23 touchdowns passes, second in the NFL—and third-highest all-time to that point.

● In a 48-10 bludgeoning of the Brooklyn Dodgers, he passed for 376 yards and six TDs, both single-game records.

● As a defensive back, he had 11 interceptions, which broke another league record.

● He averaged an NFL-leading 45.9 yards a punt, often flipping the field with a well-timed quick kick. Five of his boots were longer than 70 yards. To put this in perspective, punters not named Baugh averaged a combined 37.5 yards.

● And in the midst of one of the most amazing seasons in NFL annals he had arguably the greatest single-game performance in history: In a 42-20 win over the Detroit Lions on Nov. 14, Baugh fired four touchdown passes, intercepted four passes and got off an 81-yard punt, the longest of the year in the NFL.

About the only things Baugh didn’t do in 1943 were score a touchdown or kick a field goal or extra point. Fullback “Anvil” Andy Farkas and wingback Wilbur Moore supplied all the rushing TDs for the Redskins that season, and ends Bob Masterson and Joe Aguirre handled the bulk of the placekicking. Even a Hall-of-Famer like Baugh had his limits—especially on those folding-table legs.

* * *

Running a short-passing game akin to a West Coast attack—the “great equalizer,” he called it—Baugh led the NFL in completion percentage nine times. (AP)

One of the reasons he had such a remarkable, all-around season is that he could. These were the years of multitasking, of smaller rosters and two-way players. Versatility was at a premium. This was especially true in 1943, when the NFL reduced squad sizes from 33 to 28 so its travel needs wouldn’t infringe too much on the war effort.

By then, too, it was getting harder to find able-bodied men, what with so many of them streaming into the military. The Pittsburgh Steelers and Philadelphia Eagles dealt with the scarcity by merging, creating a “Steagles” team that finished a game out of first in the Eastern Division. The Cleveland Rams went a step further and shut down for the year. More than a dozen of their players were lend-leased to other clubs. The result was an eight-team league that still had quite a few marquee names—Baugh, the Chicago Bears’ Sid Luckman, Green Bay’s Don Hutson and others—but was short on depth. So much so that the Bears talked Bronko Nagurski, who had been retired for five seasons, into putting on a uniform again.

That’s why Baugh, who before the war usually played only half the game, often went the full 60 minutes in 1943. It also helps explain why his statistics spiked dramatically—his touchdown passes from 16 to 23, his interceptions from five to 11. He might have been having a career year, sure, but he was on the field more, too. And he was hardly alone. Blocking back Ray Hare, according to one accounting, missed only 13 minutes in 12 games, playoffs included.

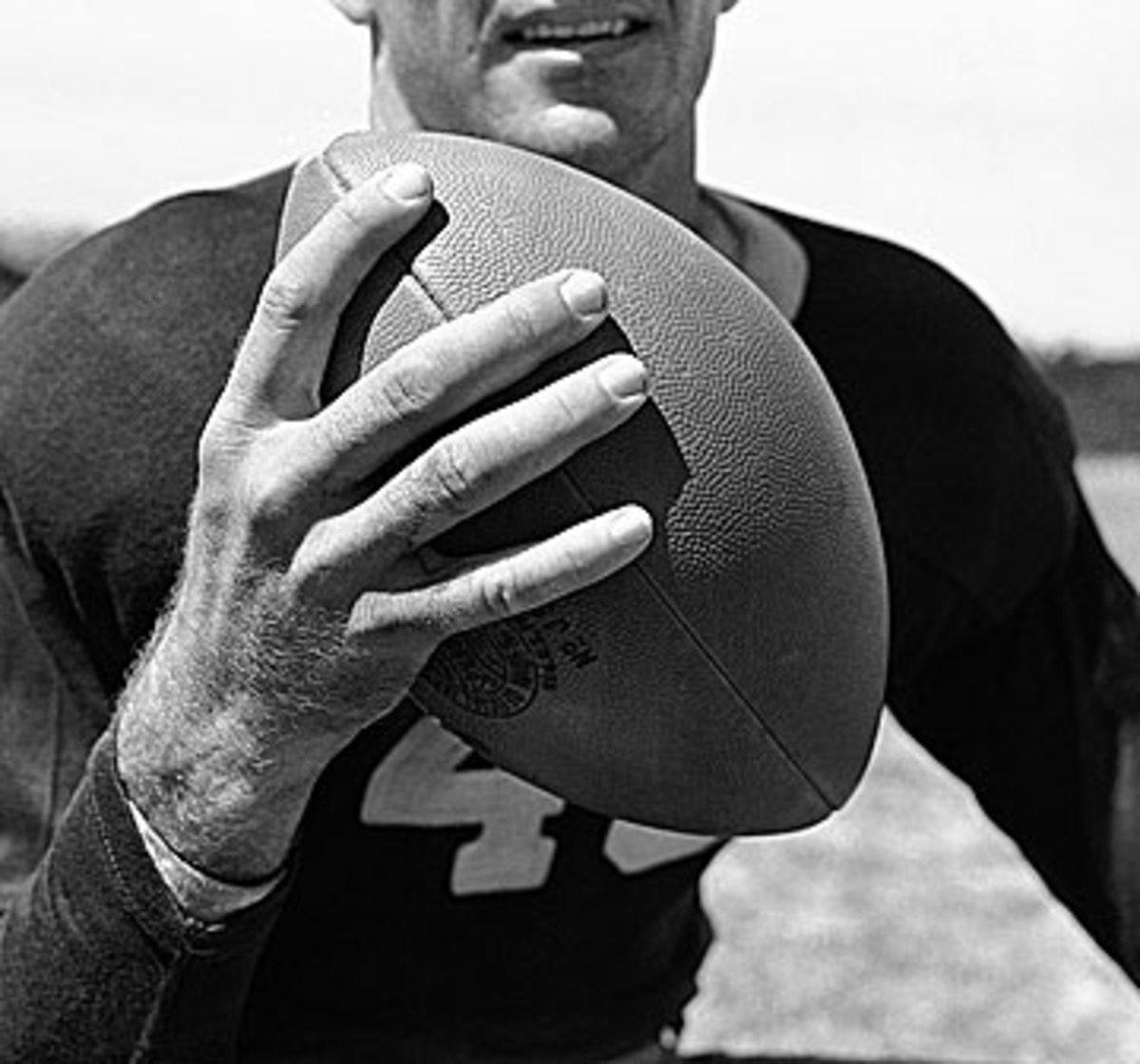

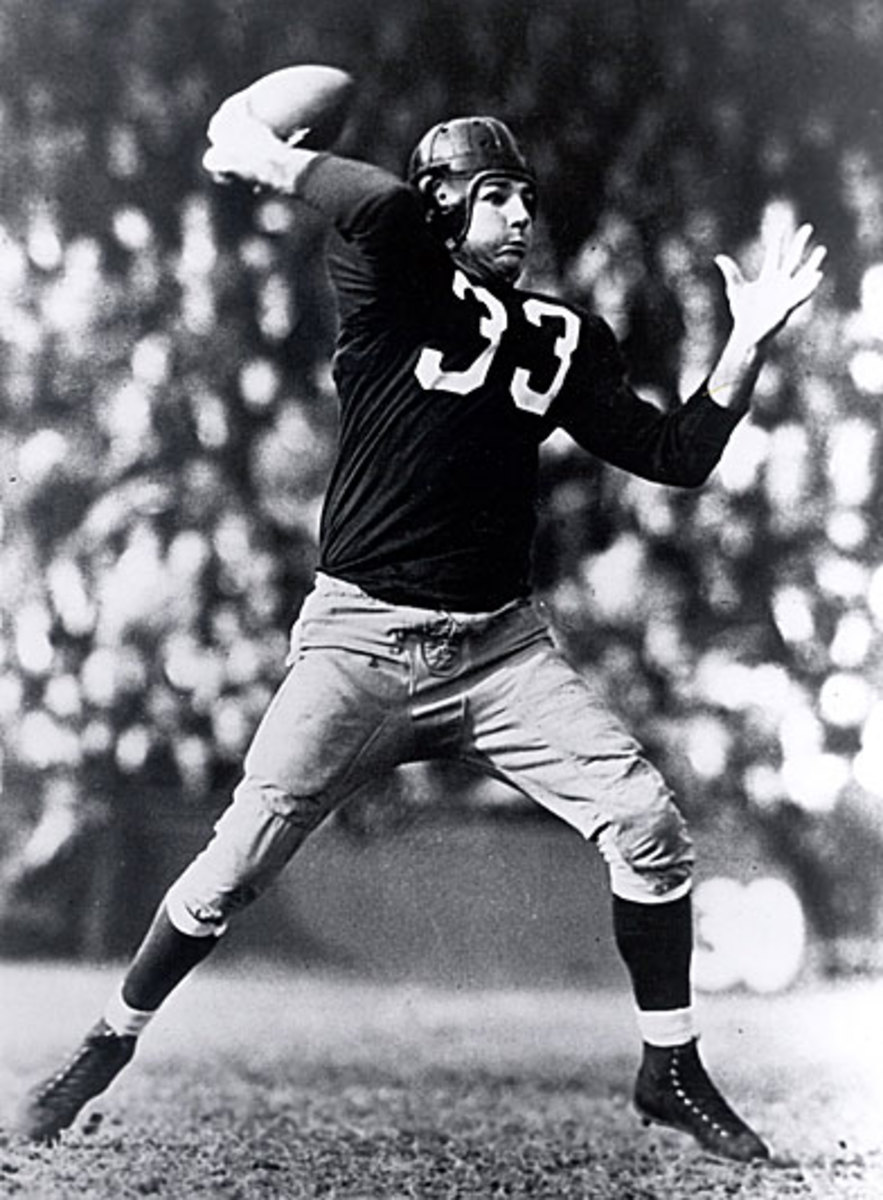

Baugh gripped with his fingers on the seams rather than the laces for better control. (JFL/AP)

It was still a single-wing world in ’43, though the Bears’ revolutionary T formation had begun to make inroads. The Redskins ran the offense as well as anybody, and Baugh, with his extraordinary accuracy, was the key. He didn’t hold the ball by the laces, the way most passers did; he held it by the seam, the laces in his palm. It gave him more control, he said.

“If it was a muddy day, or if I wanted to put a little extra distance on the ball, I would go with the laces,” he once told me. “But just the average pass, I would throw off the seam.”

If you use your imagination, you can see the beginnings of the West Coast offense in the Redskins’ attack in those years. For one thing, Baugh was a disciple of the short passing game—as taught to him by Dutch Meyer at TCU. For another, he loved to throw to his backs. In Sammy’s big game against Brooklyn that season, Moore had 213 receiving yards, still the NFL record for a back. That was the beauty of the wingback; you could throw to him, bring him around for a handoff, do all kinds of things with him.

To Baugh the logic was inescapable. The short passing game is “the great equalizer,” he said. “Even if you’re the weaker team, if you’ve got a good short passing game, you can hit that seven- or eight-yard pass, keep the other team from putting the big rush on you, and then run twice for the first down. And while you’re doing this you’re using up the clock and keeping the other offense off the field.”

As for targeting his backs rather than his ends, you have to understand: The ends in that era generally weren’t the whip-fast creatures they are today. They had more important duties than just getting open for a pass. On offense they essentially functioned as tight ends, though in obvious throwing situations they might split out.

“It was different times,” Baugh said. “The end’s first job was to be able to block and play defense. It was a little different when you went to the T formation because you spread men out more and it took a different kind of end. In the single wing, we didn’t have speed anywhere but our backs and our wingback. We were always looking to get a linebacker covering the halfback. I guarantee you, I threw more to my backs than anybody in football.”

The numbers bear him out. Redskins backs that season caught 81 passes for 1,161 yards and 13 touchdowns, with Moore’s 537 receiving yards ranking second in the league. The ends’ totals were 58 catches, 676 yards and 11 touchdowns. Baugh still called more runs (320) than passes (254), but 24 of the team’s 31 offensive touchdowns came through the air. No other club operated like that. Only the futuristic Bears even came close.

* * *

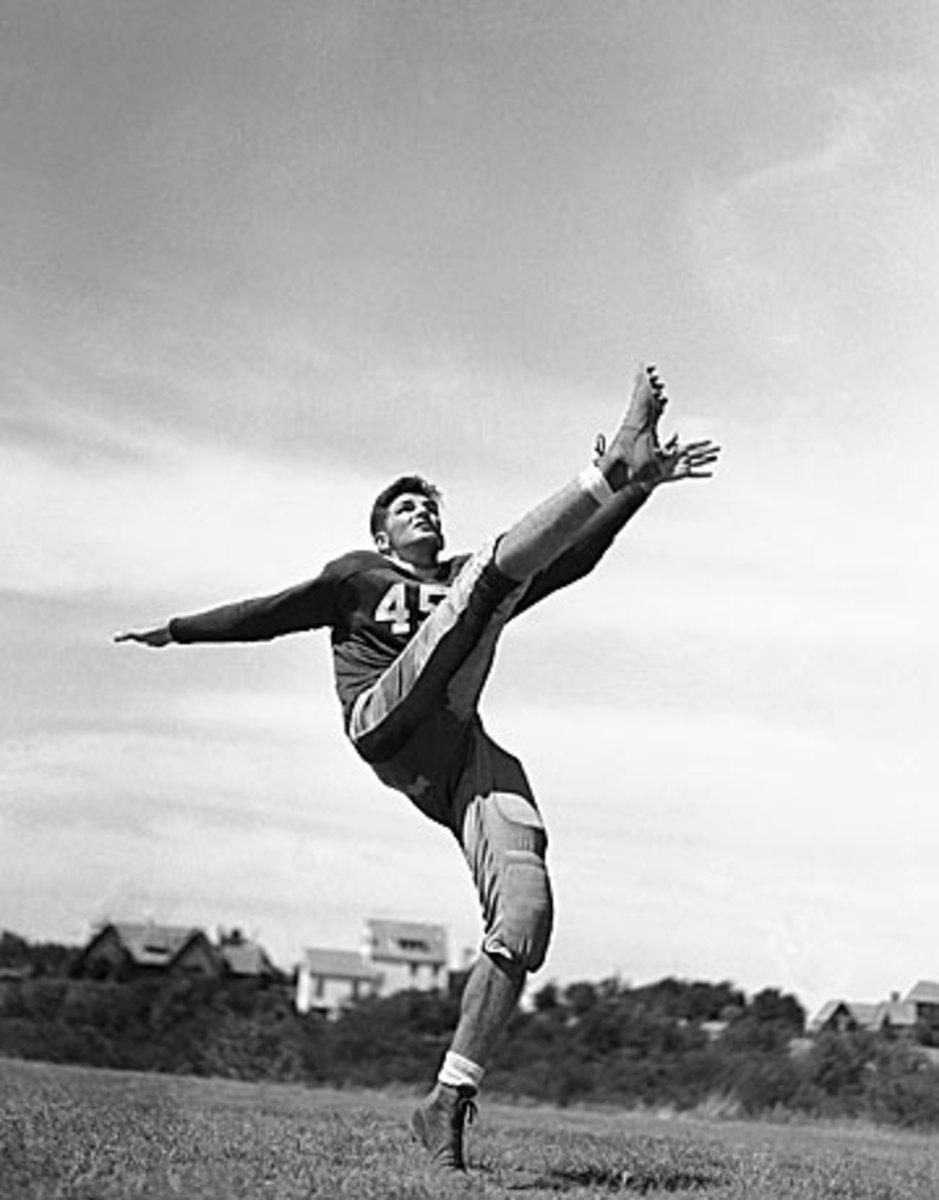

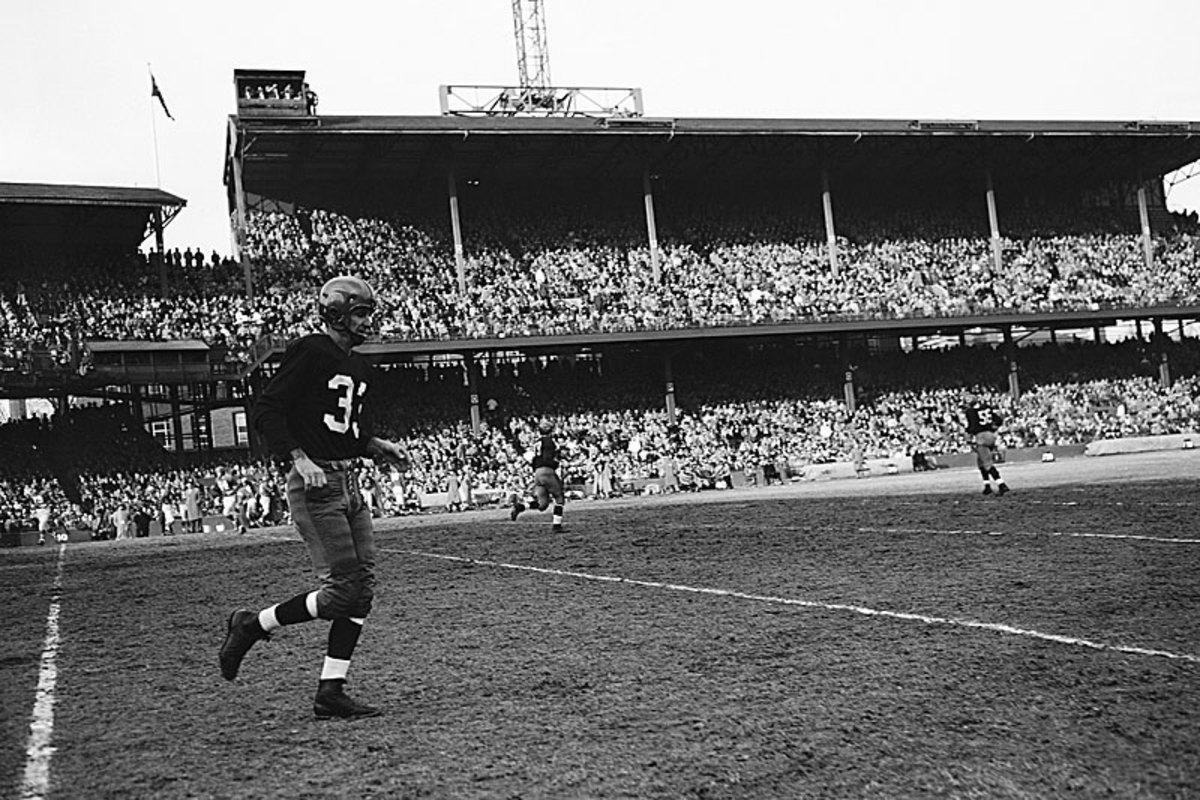

A master of the quick kick, Baugh would use the tactic as a field-position weapon; it undoubtedly boosted his yardage totals since there was no one back to field the punt. (International News Photos)

What also set the Redskins apart was Baugh’s deadly quick-kicking. While very modern in his approach to the passing game, Baugh remained a strong believer in punting before fourth down, a practice that had begun to fall out of fashion. As offenses opened up and more points were scored, teams became reluctant to give up the ball before they had to. But Baugh still used the ancient weapon to dictate field position—and to discourage the opponent from crowding the line of scrimmage and trying to clamp down on the short stuff. He’d just take the snap, kick one over the safety’s head and watch it roll.

“You’d use a rocker step,” he said. “Just kind of rock back and kick that ball. My style was a little different than most of them. In the Southwest you’re going to get a lot of wind, and I was taught that you couldn’t hold the ball real high. You had to kick it from a lower position, drop the ball lower. Less margin of error.”

The Texas native honed his punting skills as an All-America at TCU. (JFL/AP)

Trajectory was another consideration—the lower the better, so the safety couldn’t hustle back and catch the punt on the fly. It was all about getting the ball downfield before the defense could react.

“That’s the only time we’d really try to kick it down the middle of the field,” he said. “[On a regular punt] we would always go for one sideline or the other. ‘Punt to the right on two. Punt to the left on two.’ That’s how we’d call it. But on a quick kick you’d try to kick it right down the middle, right over that safety’s head. Because your linemen, they make an offensive charge, see? They block like you’re going to run through the middle. They had to make those [defensive] linemen keep their hands down. And you had to get it off pretty damn fast” because the tailback lined up only seven yards deep.

All five of Baugh’s 70-plus-yard punts in 1943 were quick kicks—which, naturally, had a healthy effect on his punting average. In the big game against the Lions he quick-kicked on first down three straight times in the early going, for 54, 46 and 66 yards. “The third shoved the Lions in a hole on their 8-yard line,” the Washington Post said, “and after [Harry] Hopp kicked feebly out Baugh pitched for a score.”

All of Baugh’s many talents were on display that year. Twice, if the newspapers are to be believed, he made touchdown-saving tackles on kickoff returns. Another time he scooped up the ball after a field-goal try was blocked and would have gone 90 yards for a score if the Giants’ Ward Cuff hadn’t made a diving stop.

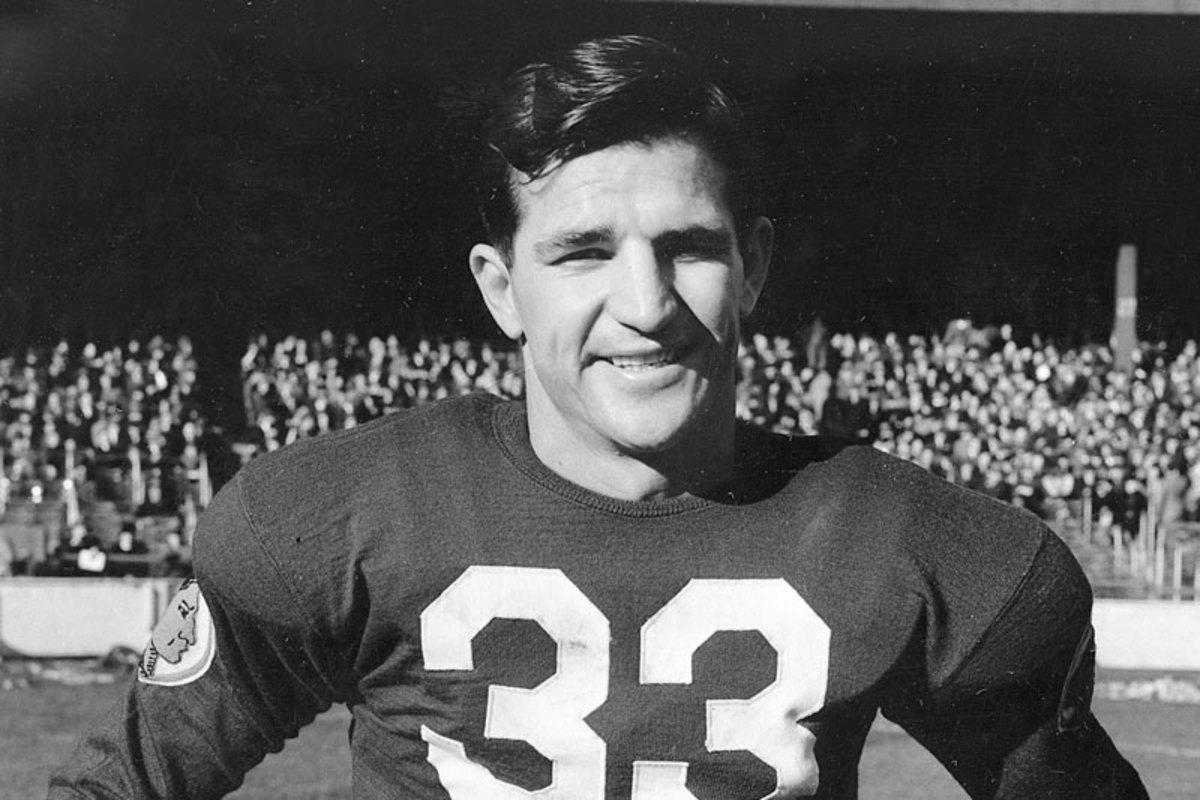

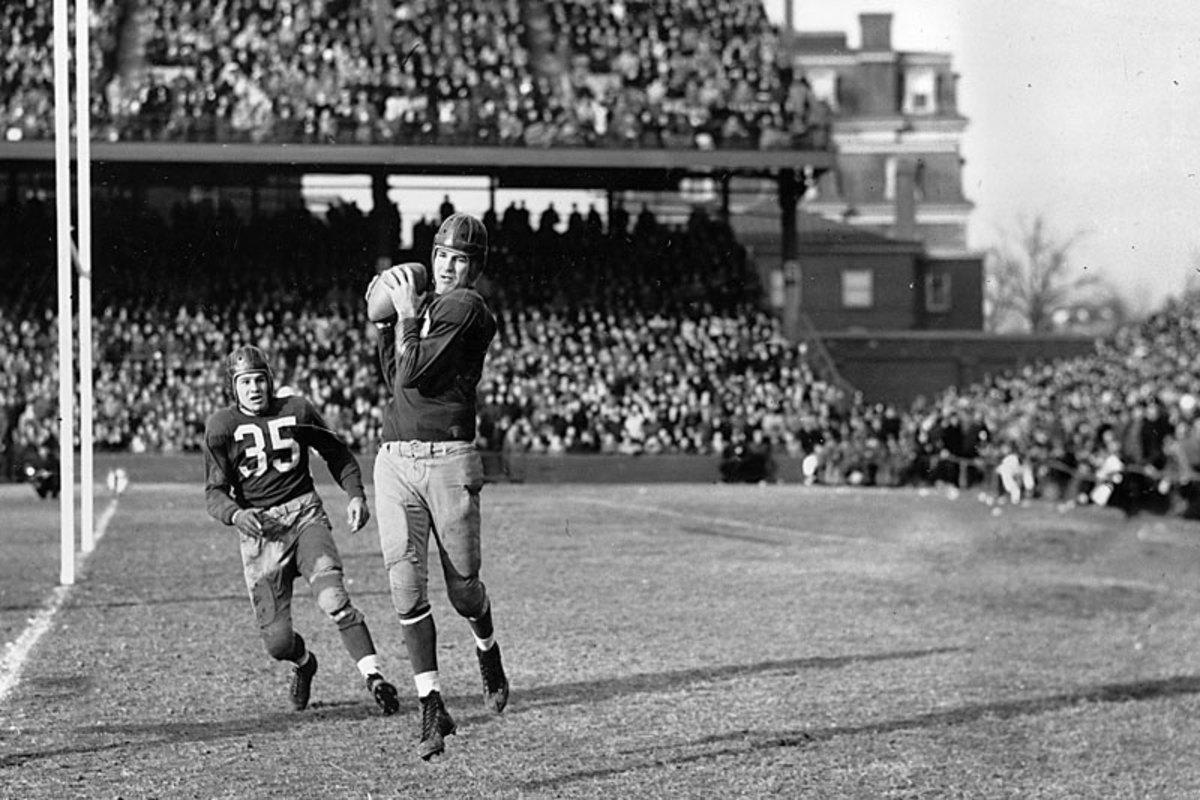

Then there was his work as a defensive back. He had a terrific sense of anticipation—as you’d expect. He was, after all, a quarterback. Of his four-interception day he recalled:

“We’d noticed in the films that [Lions passer Frank] Sinkwich had thrown for a couple of touchdowns on down-and-outs. And I thought: He’ll try to do the same thing to me. Quarterbacks form certain habits. So I stayed in the middle of the field and didn’t move [toward the sideline] until the ball was snapped and he was dropping back. Sure enough, I guessed right every time. After the first two I intercepted, I thought: Well, he’s going to come back with the post. And he damn sure did.”

Victory followed victory. Only a 14-14 tie with the Steagles (the team cobbled together from the Eagles and Steelers because of the depleted wartime rosters) kept the Redskins from extending their winning streak, carried over from their 1942 championship season, to 17 games. (Not that a 16-0-1 run wasn’t impressive enough. In fact, it remains the best in franchise history.)

The crowds were huge, war or no war. People needed their entertainment, and what was more fun than the sight of Sammy Baugh slingin’ the ball around? Every home game at Griffith Stadium was a sellout, 35,540 strong, and visits to Philadelphia (32,541) and New York (51,308) also drew packed houses. One Redskins fan even complained about ticket scalping in a letter the editor of the Post. Not only was it illegal, he argued, but it was also unfair to servicemen, “most of whom are in town just for the weekend and cannot purchase tickets” in advance.

Baugh making one of his four interceptions against the Lions at Griffith Stadium on Nov. 14, 1943. No NFL player has had more picks in a game. (Pro Football Hall of Fame)

When the Redskins manhandled the previously unbeaten Bears 21-7 in Washington to up their record to 6-0-1, fans stormed the field and tore down both goal posts. (Historical note: Keeping the peace that afternoon, as the referee in a four-man crew, was Sam Weiss, whose regular job was representing Pennsylvania’s 31st district in Congress.) Baugh, hobbled by a knee injury suffered in practice, played sparingly but was a major factor nonetheless. In the second quarter, at coach Dutch Bergman’s suggestion, he ran a Statue of Liberty play, and it worked just the way it was drawn up. Moore plucked the ball from Baugh’s hand as Sammy cocked his arm and ran 20 yards, untouched, around left end to make it 7-0. Later, Baugh tossed a 19-yard touchdown pass to Farkas for the second Washington score.

At that point, the Redskins looked headed to their second title in a row. In addition to their tailback’s otherworldly play, they had yet to allow a rushing touchdown. But then things started to get weird. Actually, they might have started to get weird two weeks earlier. Before the Lions game, Baugh said, owner George Preston Marshall came into the dressing room and told the players, “There’s a rumor going around that you’re throwing the game to Detroit. I just wanted you all to know about it.”

Baugh: “We just stood there with our mouths open. I often wondered: Did he do that to get us worked up, to piss us off so we’d play a better game? Or was he tellin’ us the truth?”

As the season unfolded—and the Redskins’ lead in the division disappeared—the rumors grew louder. After they lost back-to-back to the Steagles and Giants, games in which they were heavy favorites, the Washington Times-Herald reported that several players might be part of an NFL gambling investigation. The league denied there was any substance to the story, that the whispers had been checked out and found to be baseless. But it made for a turbulent few weeks in nation’s capital. Marshall was so incensed that he marched the team up to the Times-Herald’s offices and demanded evidence of foul play. None was produced.

* * *

Sammy Baugh, 1943: The Greatest Season?

Slingin’ Sammy, who played 16 seasons in Washington, was also Smilin’ Sammy. (AP)

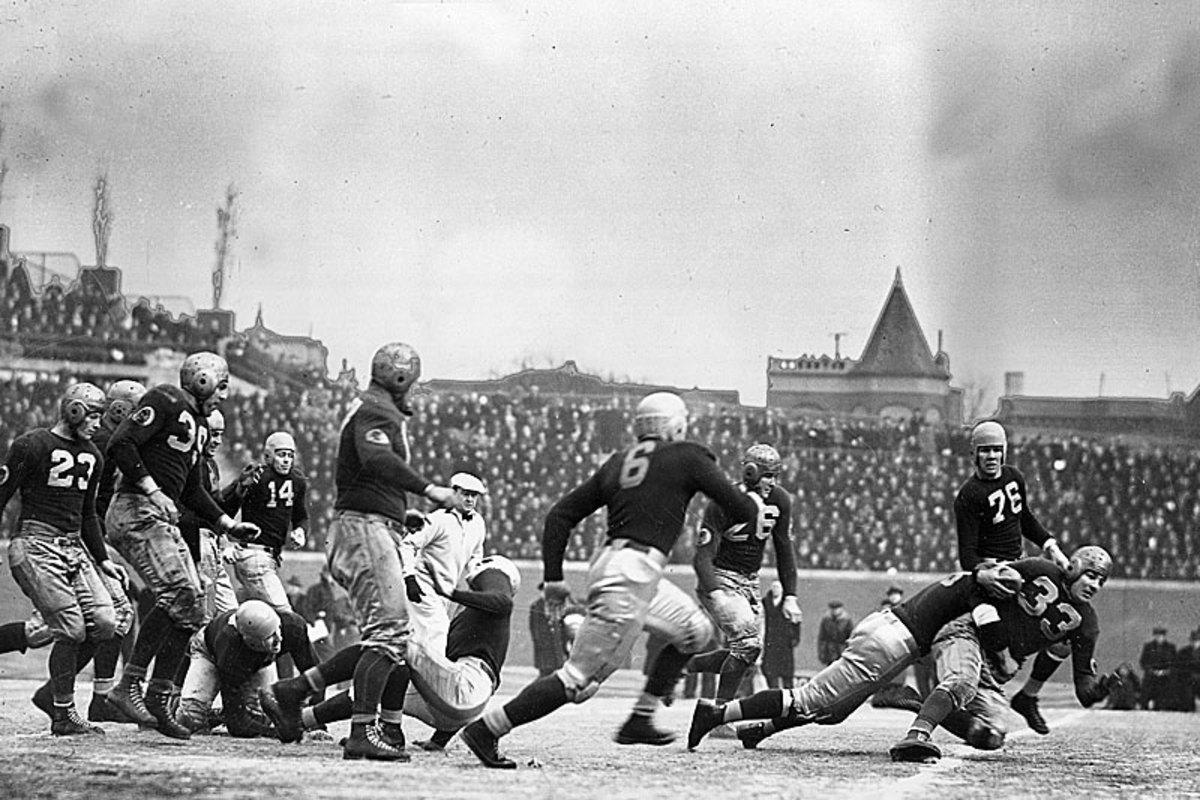

Baugh (33) being tackled during the 1937 NFL Championship Game, a 28-21 Redskins victory over the Bears at Wrigley Field. (AP)

Though rosters were depleted in Baugh’s standout ’43 season, he excelled both before and after the war too. (Pro Football Hall of Fame/AP)

1942 NFL Championship Game: Baugh’s fourth-quarter interception in the endzone sealed another title-game victory over Chicago. (AP)

Baugh leaving the field in the last game of his 16th and final NFL season, in 1952. (AP)

Swarmed by fans after his farewell game in ’52. (HB/AP)

Pictured in 1999 with a young Peyton Manning. (Gregory Heisler/Sports Illustrated)

Baugh at his ranch in Rotan, Texas, in 1994. A member of the Hall of Fame’s charter class in 1963, he died in 2008 at the age of 94. (Phil Huber /Sports Illustrated)

Sammy Baugh’s Redskins helmet. (Pro Football Hall of Fame)

A more reasonable explanation for the Redskins’ swoon was that they were banged up. Baugh’s knee was bothering him; Moore, his favorite receiver, had a similar injury; and several others were either playing hurt or too hurt to play. With little in the way of reserves, the team simply hit a wall.

But Baugh and the Redskins did have one fabulous performance left in them. After losing a third consecutive game, and second straight to New York, to force a playoff for the Eastern Division title, they returned to the Polo Grounds and pounded the Giants 28-0, holding them to four completions in 20 attempts.

Baugh’s stats were substantially better: 16 of 21 for 199 yards and a touchdown. He also had a 66-yard quick kick “to send the Giants reeling back on their heels,” the New York Times reported, along with a pair of interceptions. Pick No. 1, in the third quarter, put a halt to the first serious New York drive. Pick No. 2—and Sammy’s 40-yard runback to the Giants 5—came in the fourth quarter and set up the third Washington TD, the one that put the game away. And he did all this, mind you, while wearing sneakers, which provided better traction on the frozen turf.

(FYI: Those two interceptions gave Baugh 13 for season, playoffs included—13 in 12 games. The all-time record is 14, set by the Rams’ Night Train Lane in 1952 in a 12-game schedule. You could make the case, then, that only one player in history has had a better year for picks than Sammy did in ’43.)

While the Redskins-Giants triple feature was running its course, the Bears, winners of the Western Division, were back in Chicago, sharpening their claws and trying not to lose their edge. Thanks to the quirky scheduling in the early NFL, their regular season had ended two weeks before Washington’s—and the playoff made their layoff even longer. By the time the two clubs met for the championship, it would be 28 days since the Bears had clotheslined anybody.

Nagurski killed some of the time on his farm in Minnesota. Luckman busied himself with preparations to enter the merchant marine in January. As formidable as the Monsters of the Midway were—and they were on a 34-3-1 tear since late 1940—there was concern in the Windy City that the team would go stale, especially since George Halas wasn’t around to crack the whip. He had enlisted in the Navy the year before and left the coaching to assistants Hunk Anderson and Luke Johnsos. That seemed to be the wounded Redskins’ best hope: jump on top early, while the Bears were knocking the rust off, and try to hold on.

And the Redskins did score first, at the start of the second quarter, on a 1-yard touchdown run by Farkas. By then, though, they were in deep trouble, despite being up 7-0. While covering a punt in the opening minutes, Baugh had taken a hit on the head—either from a knee or the hard ground—and suffered a concussion. He spent the rest of the half, and some of the second, on the bench, clearing the cobwebs.

That’s all that’s missing from this story, this homage to Sammy Baugh’s spectacular 1943—a happy ending. Instead of Baugh’s leading the Redskins to another title, we have Baugh wrapped in a parka on the sideline, tears trickling down his face, hazily asking teammates, “Why won’t they let me play?”

When he did return to action, Washington was down 21-7 and Luckman was in the process throwing five touchdown passes, a record for an NFL championship game that stood until 1995. Sammy threw two in the time that remained, but lord knows how. His brain was so scrambled that he had to ask for help in the huddle. “Baugh kept telling them to correct him if he called the wrong play,” the Post reported. The Bears, never averse to running up the score, onside kicked with a 20-point lead to set up their final TD in a 41-21 victory.

* * *

(AP)

Over the decades Baugh’s season has disappeared in the mists. Maybe it’s because it came against wartime competition. Maybe it’s because he didn’t win the title. Maybe it’s because Luckman, on the strength of his record-breaking passing (2,194 yards, 28 touchdowns), was voted the league’s most valuable player. Or maybe it’s because 1943 is, to many, as distant as the dinosaurs.

It bears mentioning, though, that Baugh didn’t do much that year that he didn’t do other years, when the NFL was at full strength—which takes some of the steam out of the war-weakened-league argument. He had a significantly higher completion percentage in 1940 (62.7 to 55.6), and in ’47 he threw for more touchdowns (25 to 23) and far more yards (2,938 to 1,754). His punting average (45.9), meanwhile, wasn’t as high as it was in ’40 (51.4) or ’41 (48.7). Only his interception total (11) was off the charts, and that was due, at least in part, to playing more on defense. (Most years he was good for four or five picks.)