Richard Sherman Refuses to Go Quietly into the Night

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Seahawks coach Pete Carroll greets Richard Sherman’s family at the team party. (Robert Klemko/The MMQB)

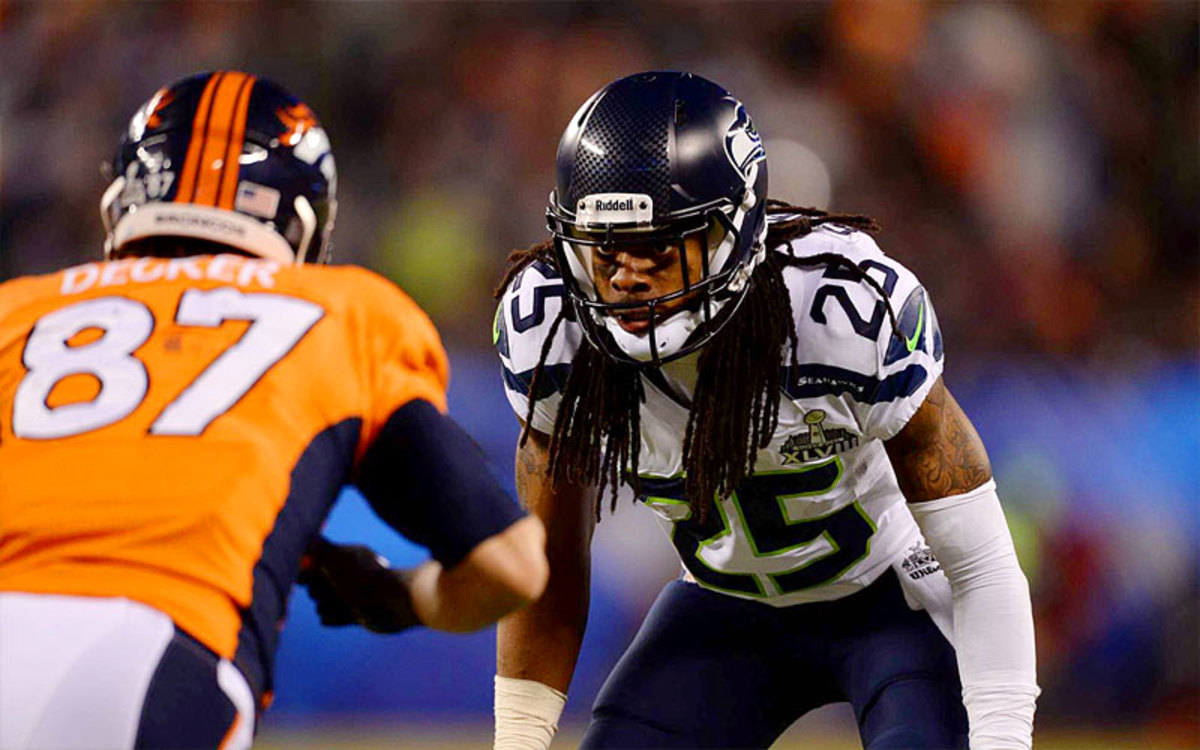

From now until the start of training camps, The MMQB will be running a series of our Greatest Hits from the site's first year. Here, Robert Klemko trails Seahawks All-Pro cornerback and MMQB columnist Richard Sherman after he wrapped up a whirlwind season with a victory in Super Bowl XLVIII.

JERSEY CITY, N.J.— Centered in a family bubble in the corner of the room, not far from the all-night turkey buffet and the speaker pumping Kool and the Gang’s “Funky Stuff,” Richard Sherman greets a most-welcome intruder with a wide grin. Coach Pete Carroll emerges from a darkened hallway at the Westin Hotel at 1:30 a.m. to greet Sherman’s family, haloed around the Seahawks’ All-Pro cornerback whose right foot is encased in a walking boot. Wedged into the same chair, his girlfriend sits at his side. His mother and father sit across from them, flanked by friends and family. Carroll splits the group and leans in, clasping Richard’s hand in his.

“After everything you’ve been through, you did it,” Carroll says, rubbing the blue beanie that sits atop Sherman’s head. “I’m so proud of you.”

Though injured, Sherman was still able to take in the celebration. (Jeff Gross/Getty Images)

They share a few quiet words, and then Carroll is off to rejoin the party raging in rooms next door and above. The Seahawks won Super Bowl XLVIII with perhaps the greatest high-stakes defensive performance in modern football history. Peyton Manning was pressured, sacked, intercepted and felled, and now it’s time to savor the 43-8 victory and utter domination. Somebody hands Sherman a drink, but he nurses it for so long that another arrives before he’s done. Now double-fisting Hennessy on ice, all he wants to do is talk football.

“All we did was play situational football,” Sherman says. “We knew what route concepts they liked on different downs, so we jumped all the routes. Then we figured out the hand signals for a few of the route audibles in the first half.”

He demonstrates the signs Manning used for various routes, and says he and his teammates were calling out plays throughout the game and getting them right. “Me, Earl [Thomas], Kam [Chancellor]… we’re not just three All-Pro players. We’re three All-Pro minds,” Sherman says. “Now, if Peyton had thrown in some double moves, if he had gone out of character, we could’ve been exposed.”

The room Sherman looks out upon is painted in Seahawks green and blue, as if the rest of the color wheel has been suspended for one night in Jersey City. Green and blue stage lights dance on the walls. A nearby table is stocked with dozens of chocolate cupcakes topped with grey icing and green and blue skittles, most of which go untouched. Sherman’s mother, Beverly, wears tightly coiled bangs, neon green rain boots (which she found at an Inglewood Marshalls) and a blue authentic Richard Sherman No. 25 jersey with MOM stitched across the left collarbone. She had wailed, “My baby!” upon seeing him at MetLife, but is relatively quiet at the party, smiling as she watches her baby talk with his dad. His father, Kevin, is draped in a black and blue leather jacket, custom-made when Richard was a rookie to say SHERMAN #25 on the right breast and DAD on the left. He leans in and says in a deep, raspy voice: “I don't know what I'm going to do with myself now. No more football.”

“The NFC Championship was the Super Bowl,” Sherman says. “The 49ers were the second-best team in the NFL.”

His son laughs, but he doesn’t really know either. A 25-year-old from Compton, a Stanford grad and the son of garbage man, Richard Sherman has become a sudden pop-culture icon, with dozens of interview requests pending and several marketing deals already in negotiation; it is the result of three seasons of stellar play and one volcanic explosion on live television following the NFC title game. At the heart of it all lies football, which is why tonight is so sobering for the fifth-round pick who should be running around and partying on top of the world. He was sure he’d snapped his ankle in the second half. He heard a pop, and that’s why he stayed on the ground for several minutes, which felt like eternity to Seahawks fans. An X-ray showed no break, and it’s believed to be nothing more serious than a high-ankle sprain, pending the results of an MRI.

Fitted with a walking boot during the final minutes of the blowout, Sherman gingerly made his way to the field celebration, then to the press conference podium and back through the tunnel toward the locker room, whereupon Marshawn Lynch saw his crutches and guffawed, “What the f—?” through a black face-warmer that the running back worn under a red “Beast Mode” hoodie. Sherman smirked and answered simply, “I’m not Beast Mode.”

Richard Sherman Refuses to Go Quietly into the Night

Ronald Martinez/Getty Images

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Gary Bogdon for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

John Biever/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB

Back in the locker room, Sherman returned from the showers with the help of crutches while teammates devoured BBQ and mac and cheese. His older brother, Branton, picked three pieces of blue and green confetti out of Sherman’s dreadlocks before he got onto a cart that took him to the car that would transport him to the party, 20 minutes southeast of East Rutherford at the team hotel. After Sherman left the stadium, one New Jersey State Trooper in his dress blues said to another, “That broken ankle might keep him out of trouble tonight.”

“Yea,” the other replied.

Sherman might be trouble, but not the kind of trouble they were talking about. He’s trouble for elite quarterbacks. Trouble for PR guys. Trouble for those who prefer athletes to always be gracious and obedient. Encircled in that bubble at 2 a.m., the truth about the 2013 season spills out like molten rock, interrupted only when hotel staff or the family and friends of teammates ask him for autographs.

* He finds Media Day obnoxious, and wonders why the NFL credentialed so many people to cover Super Bowl week.

* He hates to admit it, but says “the NFC Championship was the Super Bowl. The 49ers were the second-best team in the NFL.”

Sherman and Marshawn Lynch at the team hotel after the game, with no curfew early Monday morning. (Robert Klemko/The MMQB)

* At the beginning of the week Carroll imposed a 1 a.m. curfew, but asked his leaders if it was a good idea; they suggested one night off at the beginning of the week. They got last Monday. “That takes humility on his part,” Sherman says.

* He’s not sure if he’d have been able to play in two weeks if he had to. After first injuring his ankle earlier in the game, he says the coaches wanted him out there despite his diminished ability to serve as a deterrent to Peyton Manning. “I looked sloppy out there,” he says. “They only kept me out there by reputation.”

* And he’s not just being coy when he says he had only good intentions when he tried to shake 49ers wide receiver Michael Crabtree’s hand after the game-clinching deflection and interception in the NFC title game. “I know if I went up to Larry Fitzgerald in that situation,” Sherman says, “he’d have shaken my hand. It’s about respect.”

It’s as if the light never goes off with Sherman; it just fades in and out, but mostly in. By 3:10 a.m., his parents have hugged him goodbye and he remains in the same seat he took up two hours ago, next to the same woman. The room has thinned out and Sherman fills the void with his growing excitement. The pain, the booze, a belly full of turkey—somehow it all makes him think faster. He’s on a roll now, speaking clearer than he did at the podium four hours ago.

An assistant coach, Marquand Manuel, comes over and greets Sherman with a smile, congratulating him. Almost immediately they start speaking another language. Digs, crossers and seams are the new patois. They laugh upon rediscovering the moment in XLVIII when they knew they were “playing chess, not checkers,” as Sherman tells it.

“A good offense that has really studied film and really done its due diligence will see plays that other teams have had success with and install them as a surprise,” Sherman says. “Brandon Browner got beat in Arizona on posts from two outside receivers, and flats from the slot receivers. And they were the only team that ran it. Kam was the safety and he tried to undercut the post and they just banged it in there. Denver had never run it, and they put it in because of Arizona. That’s chess.”

Sherman on Broncos wideout Demaryius Thomas. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

By 3:45 a.m., only friends remain. Bedtime nears. Sherman has passed off one glass of Hennessy to his girlfriend, Ashley,and another rests in his hand, the ice nearly melted. An adult couple in Seahawks jerseys introduce themselves, wanting to congratulate Sherman. The man has a question: “My daughter is considering Stanford. The town seems uptight. What’s it like?” Sherman’s answer is thoughtful and lengthy. “Palo Alto is very different from campus. Palo Alto is for older people,” he says, in part. “Stanford will allow her to meet some of the most intellectually stimulating people in the world. Her classmates will be people like the CEO of Instagram.”

Sherman’s father, Kevin, comes from a much different background. Despite his son’s riches—and Richard’s contract will only get bigger from here—the elder Sherman still wakes up for his early-morning trash route to meet the personal challenge of making his pension. It was Kevin Sherman who came to mind when Richard found himself in Carroll’s office after that infamous NFC title game rant, being asked in a fatherly way, “What were you thinking? Let’s figure out what you want to gain here, so I can help you get it. I want them to know the Richard who leads my team, who does all the community service…”

It was virtually the same chat Sherman had with Carroll in October 2012, after the second-year corner intercepted Tom Brady in a victory and then mocked the Patriots’ quarterback in person and on Twitter after the game. Carroll asked then, in the same manner, “What are you trying to do?”

Sherman’s response: “I want to be All-Pro. I want to be seen as the best, right now, and to do that I have to be loud.”

At 4:08 a.m., Sherman is on his feet. The celebration continues to roar upstairs, and Sherman wants to see at least a portion of the concert. Ashley helps him up, hands him his crutches and holds his drink. He gets to the elevator just as Lynch and a half dozen of his friends pour in, stumbling like children run amok. Lynch is still stiff and cool, still wrapped in the same face-warmer, hoodie up. Lynch has been telling teammates all season he’ll retire if they win the Super Bowl. Sherman doesn’t believe him. In the lobby upstairs, they put their heads together and Lynch whispers something inaudible through the mask. Sherman laughs and screams, “You reneged!” Fans at the concert see Sherman and begin sloppily chanting, “L-O-B! L-O-B!” He leaves Lynch, sticks his crutches under his arms and disappears into the crowd. The night is not over yet.