The Battle of Washington

With special reporting by Emily Kaplan

SAN CARLOS, Ariz. — The dusty roads behind the San Carlos Apache tribal headquarters lead to a place where the debate surrounding the NFL team in the nation's capital does not feel 2,000 miles away. This reservation, a 1.8 million-acre trust of land two hours east of Phoenix, has an air of isolation. Cell phone service is spotty, and many businesses don’t have the technology to swipe credit cards. The dwellings of the 10,000 plus residents are scattered across the semi-arid terrain.

But the issue of the Washington NFL team’s name—the Redskins—drives the work of one artist on a daily basis. Propped up outside the white trailer that serves as his studio are paintings of Apache men and women on mixed media such as skateboards and household doors. Douglas Miles’ work portrays his subjects in traditional dress of cloth headbands and high-topped moccasins; wielding revolvers in a modern twist on their warrior ancestors; celebrating the tribe’s matrilineal heritage.

About a year and a half ago, Miles, who has lived on the reservation for nearly three decades, started an art campaign called “What Tribe,” with the intent of dismantling racial stereotypes such as the ones he sees in that team name and logo. Instead of a protest or a picket sign, he decided to weigh in by presenting his culture in a way many Native Americans feel is not recognized by the larger American populace. “We’re either seen as this extreme noble savage,” Miles says, “or this extreme poverty case that needs help.”

Indeed, these are the two visages often evoked and juxtaposed in discussions about the Washington team name. The push for a change in the name is pitted against Native Americans’ less-abstract needs—job creation, health care, land rights. But in many Native American communities, and to many Native American leaders, the mascot issue is about more than a football team.

Artist Douglas Miles on the San Carlos Apache reservation in Arizona. (Jenny Vrentas)

That’s what we saw and heard during the past month, when The MMQB visited three Native American communities—the San Carlos Apache Reservation, Onondaga Nation in upstate New York and the Seminole Tribe’s Big Cypress Indian Reservation in South Florida—and spoke to dozens of other Native Americans living across the U.S. We spoke to leaders and to everyday people in the community like Miles, whom we met at the local café in San Carlos where his daughter works.

The recent groundswell around the team name produced some movement earlier this month, when the franchise announced the launch of the Original Americans Foundation, which pledges to work with tribal communities to provide resources and opportunities. Team owner Daniel Snyder and his staff visited 26 Native American communities to gather information and assess needs, and their initiative has already had a positive and tangible impact—one project has been to distribute more than 3,000 coats to tribes in the Great Plains this winter.

But the issue of the name remains. There is a loud call from many Native Americans, one that did not ask for money or assistance from the team. It asked for a name change. In a four-page letter outlining the new foundation’s goals, Snyder did not directly address this call, but wrote, “It's plain to see [Native Americans] need action, not words.”

“I would say we do need action,” says Jacqueline Pata, executive director of the Washington, D.C.-based National Congress of American Indians (NCAI). “And one of those actions is treating Indian country respectfully. One of those actions, Dan Snyder, is changing the name. Respect Indian country, do what is right, and don’t cloak it with something else.”

At least a dozen members of Congress want the name changed, as do some civil rights groups and vocal members of the national media. The people at the heart of the debate, though, are those at the grass-roots level among the more than 500 recognized tribes in the U.S. The MMQB took the temperature of Native Americans from coast to coast—representing 18 tribes in 10 states—and found a complicated and nuanced issue. What we did not find: the “overwhelming majority” that Snyder and NFL commissioner Roger Goodell have claimed support the name “Redskins.”

We found opponents of the name in 18 tribes: veterans of the U.S. military, lawyers, college students, cultural center employees, school volunteers and restaurant servers. Their viewpoints align with official statements from dozens of tribes or inter-tribal councils and from the NCAI, which represents more than 250 tribal governments at the Embassy of Tribal Nations. Many of these people wondered how, or if, their voices are being counted.

By no means is there a consensus. We met a man in San Carlos who grew up rooting for Joe Theismann. Others pointed out how the Florida State Seminoles and Central Michigan Chippewas use Native American mascots with the approval and input of the tribes. Some whom we spoke to on the San Carlos and Big Cypress reservations said they had no opinion, and members of about a dozen other tribes or communities we reached out to did not respond or declined to be interviewed.

But team officials and the NFL paint a nearly uniform picture of support for the name, typically citing the results of a 2004 survey by the Annenberg Public Policy Center, that 90 percent of the 768 self-identified Native Americans polled said the team name “Redskins” did not bother them. (The question: “The professional football team in Washington calls itself the Washington Redskins. As a Native American, do you find that name offensive or doesn’t it bother you?”). That survey is 10 years old. Can the same opinion be applied today?

Voices

John Warren, Chairman of the Pokagon Band of the Potawatomi, in Michigan and Indiana: “To me, I look at it as a part of an old, institutionalized racism. I don't understand why some athletes, especially the ones of color, don't say something. The ‘R’ word is just as offensive. Athletes of color should be very, very offended when they hear that word. It’s the same thing we’re talking about here. Why is it offensive to us, and not others? Does it matter that there are not as many Native Americans playing the game? It shouldn’t matter. The connotations that word has, any minority group who has had a history of oppression, they should know that it is wrong.”

Neely Tsoodle of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma: “My personal belief is completely different than anyone I know. But I don't see the need to eliminate Native Americans as mascots. In fact, I don't want to do that. At all. If we do, then we are erasing another part of our footprint in American culture. … Somewhere along the road it got out of hand, and became a caricature. Maybe it was lack of education, maybe it was society, but it turned into crazy, violent men running around beating drums with red paint on their face, and that's not OK. But that doesn't mean we should erase the name completely. We just need to make sure that the nickname is used in a tasteful manner and we are educating people about the meaning behind it. If we get rid of the name completely, we are erasing a part of our identity, and that's something I know we have fought so hard to maintain."

* * *

The Washington football team has drawn more attention than other professional sports teams using Native American names or imagery—Braves, Indians, Blackhawks—because it represents the nation’s capital, and because it uses a word critics consider a racial epithet. The NFL plans to crack down on slurs on the field for the 2014 season, emphasizing to officials that such language is part of the 15-yard unsportsmanlike conduct penalty. That raises plenty of questions—including: How does the “Redskins” debate fit in to all this?

The word “redskin” has a complex history and meaning. An early usage, as traced by Smithsonian senior linguist Ives Goddard, was as a self-identifier among Piankashaw tribesmen in the mid-1700s. But newspaper clippings from the 1800s show the word used in the darker context of the colonial authorities’ bounty offer for each “redskin” killed, during the era when scalping was practiced by settlers.

Like the n-word, it is derived from the color of a person’s skin and has acquired offensive connotations through history. And members of the group to which it applies have repurposed it among themselves, sometimes using it as an expression of kinship. But that doesn’t subtract from the word’s potency. Says 53-year-old Victor Billie, who teaches traditional carving and the Seminole language for Big Cypress, “In a way, ‘Redskins’ is a racial slur, but in a way, it ain’t. I’m divided. I leave ‘Redskins’ up to each person’s definition. If a person says to me, ‘You’re a redskin,’ I consider it the truth. I’m not black-skinned, or white-skinned; I’m a redskin. I’m proud of it. But, when I was younger, it was an insult, and it hurt me.”

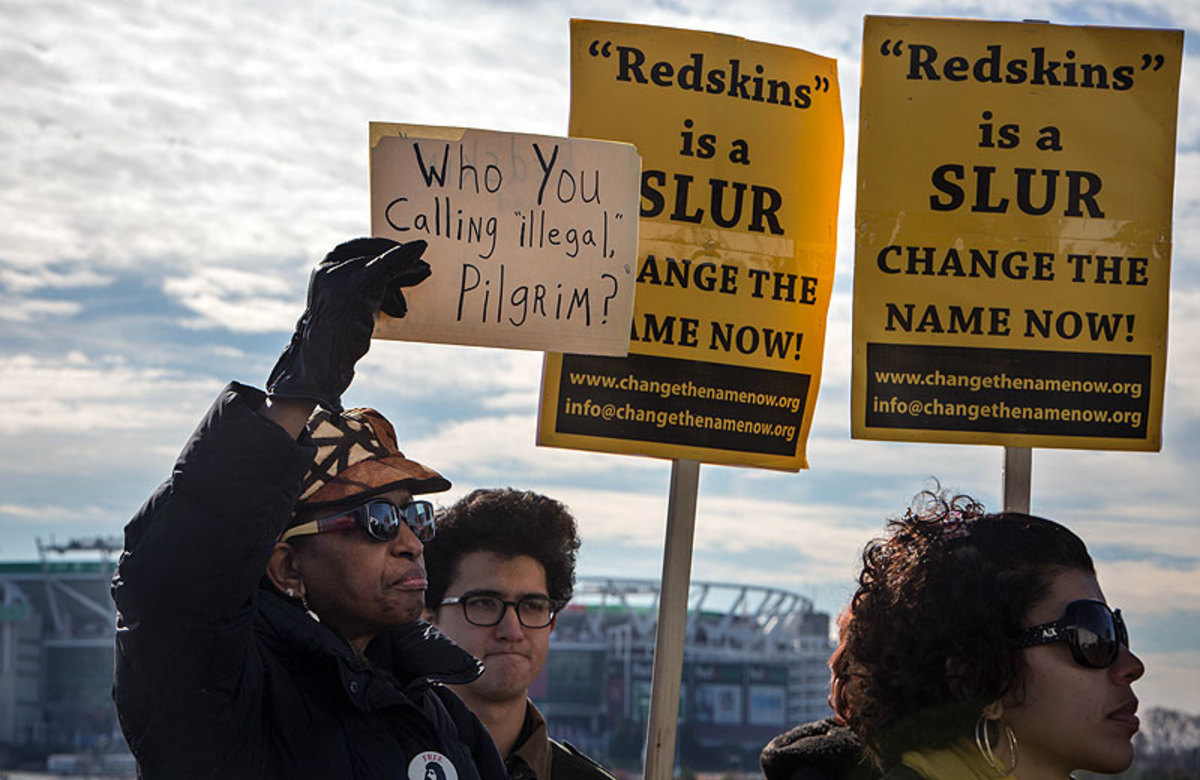

In the shadow of FedEx Field, a protest popped up at a November 2013 news conference about the Washington NFL team name issue. (Evelyn Hockstein/For The Washington Post via Getty Images)

The hurtful connotations are what many Native Americans hear in the Washington team name, often based on personal experience. Members of the Blackfeet Nation tribal council explain how they are referred to as “redskins” in Cut Bank, Mont., just outside their reservation’s border. They also recall being denied service in some restaurants in that same town. “Depending on the way you tell me [‘redskin’],” says Leon Vielle, one of the councilmen, “you might get punched in the nose, or you might get looked at mean.”

One member of South Dakota’s Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate tribe, Robert Shepherd, shared a memory of being called to the blackboard to complete a math problem as a sixth-grader in the nearby school district. When he got stuck, the teacher told him, “Go sit down, you dumb injun.” Now chairman of his tribe, Shepherd is preparing to formally oppose the “Redmen” mascot of Sisseton High School—and all Native American mascots—which he believes contributed to his experiences with discrimination.

But he would be the first chairman in Sisseton to take on this issue. The school serves both the tribe’s reservation and the border town, and some members of the tribe hold loyalty to their alma mater. There has long been debate about the Redmen name in the community. Elsewhere, tribes embrace mascots, such as the San Carlos Braves and the Ahfachkee Warriors, but the student body at these schools is nearly 100 percent Native American.

Complicated? Perhaps. But the common denominator is that Native Americans want to have a say in how words and imagery that refer to them are used, in the same way that African-Americans establish when and how the n-word can be used. “All this is, is Native American people saying you cannot dictate to me what I should like, and accept, and not accept,” says Miles. “I may only be one person, but if one person doesn’t like it, then someone needs to pay attention.”

Voices

Stephanie Vielle, 31, U.S. Marine veteran and member of the Blackfeet Nation: “Racism gets really draining. Sometimes people accept it, not because they want to, but because it has been so repetitive. That’s kind of what the Redskins represent, is our exhaustion.”

Jeremy Baker, 23, Creek and Seminole: “I think people my age and younger don’t have a problem with [the Redskins] near as much as the older people. I don’t necessarily have a problem with it. Now if you walked in here and called me a ‘redskin,’ I might have a problem. It would be different. People my age wear Redskins gear even. I don’t know why younger people don’t care. I think we’re just not as much into Native American culture, with the way we’re raised today. We’re Americanized, I guess.”

* * *

Since last fall, Snyder and his staff spoke with 400 tribal leaders, according to his open letter, and started more than 40 projects in Native American communities. As word of their trips trickled back to NCAI headquarters, many tribes reported that team officials did not ask how they felt about the name.

This was the case during a February visit to the Blackfeet Reservation in northwestern Montana, up near the Canadian border. Snyder was not present, but team representatives spent about four hours with members of the tribal council, discussing children’s programs and economic development. They made suggestions for an empty five-building industrial park the tribe is trying to turn into a foreign trade zone to create new jobs.

Leon Vielle, who participated in the meetings, admits he might not have wanted to take part if the focus had been on the team name. But the industrial park has been his pet project, so he put his strong feelings against the name aside to help his community. “I realize the controversy with the name,” he says, “but one of the things is it’s brought some attention to something that is lacking in Indian country, that is lacking within our federal government. If it takes [Snyder] to help us, then fine. We’re not looking for a handout, we’re looking for a hand up.”

Daniel Snyder. (Simon Bruty/SI/The MMQB)

The team’s approach has merit—taking the time to listen to the needs and challenges many Native American communities face. Snyder wrote in his letter that he “wanted and needed to hear firsthand what Native Americans truly thought of our name, our logo, and whether we were, in fact, upholding the principle of respect in regard to the Native American community.” The team did not describe how it chose the communities it visited, or the scope of its financial commitment. Onondaga Nation general counsel Joe Heath says Snyder was invited to their community—one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, along with the Oneida Nation, which launched the “Change the Mascot” campaign—but it was not one of the trips the team made. Nor was the San Carlos Apache Reservation, whose tribal council passed a resolution in October denouncing the “Redskins” mascot as “deeply offensive.” Says San Carlos Apache vice chair John Bush, “I’d love to share my thoughts with them.” (A team spokesman did not make Snyder available for an interview with The MMQB.)

Snyder’s outreach pleasantly surprised his fellow owners at the NFL meetings in March. Indian country, however, has been more skeptical. “You never took interest in us, going on a few decades,” says Vielle’s daughter, Stephanie, a U.S. Marine veteran who is now attending college at the University of Texas at Arlington. “I’m glad they’re helping us now, but that’s taking advantage of a poor community. It shouldn’t be shut-your-face money.”

Navajo Code Talker Roy Hawthorn at a game at FedEx Field in November. (Evan Vucci/AP)

Snyder has owned the team since 1999, and his effort to connect with Native Americans in response to the rising push for a name change has created divides in some communities—including Navajo Nation, the second-largest tribe in the U.S., which has long remained officially silent on the mascot issue. Among the tribe’s most revered members are its Code Talkers, the veterans who used their complex language to transmit coded messages during World War II. In November four Code Talkers were recognized on the field during a Washington game at FedEx Field; three were wearing team jackets. Later, at a Feb. 28 meeting of the Navajo Code Talkers Association in Arizona, seven members passed an endorsement of the team's name, though the rest of the group's 40 members were not in attendance for the vote.

In response, Joshua Lavar Butler, a delegate in the Navajo Nation Council, introduced legislation last month opposing professional sports teams’ use of Native American mascots. “Navajo Nation can no longer afford to sit back and remain neutral,” Butler says. “An endorsement by the Navajo Code Talkers is not an endorsement by Navajo Nation.” The committee voted last week to table the legislation and amend it, striking out the references to the Code Talkers.

Other aspects of Snyder’s outreach have also raised questions. His foundation will be run by Gary Edwards, a Cherokee and retired member of the U.S. Secret Service, whose selection has already been scrutinized. When Edwards was chief executive of the National Native American Law Enforcement Association, the organization received a $1 million contract from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to recruit Native Americans to work in law enforcement. But the Washington Post reported that the contract was canceled after federal investigators found the group’s work under the contract completely unusable. Pata suggests that rather than bring on Edwards, the team could have partnered with people or organizations already doing work in Native American communities, for greater returns.

“Indian country is a welcoming community—we have a history of that, right?” says Pata, a member of Alaska’s Tlingit Tribe. “But I believe the motives are disingenuous. It’s all part of that larger strategy to win at something that is important to them, which is keeping their name, keeping the franchise and keeping the dollars rolling in for the team.”

Voices

Arvina Martin, 34, enrolled member of Ho-Chunk Nation, from Wisconsin: “The most harmful thing is that these depictions are ways to keep Native people in the past, as these two-dimensional images that are very comfortable to most Americans to keep Indians in that sense. A lot of people do seem to care more about these images than real Indian people who are sitting there and talking to them. And that to me is insane as well, a living breathing person standing here talking, saying, ‘This isn’t appropriate, and let me tell you the reasons why,’ and dissenters just saying, ‘Nope, don’t care.’ ”

Herb Stevens, director of the San Carlos Apache Cultural Center: “It’s an honor to be recognized as being ‘Native,’ but not to be called a redskin.”

* * *

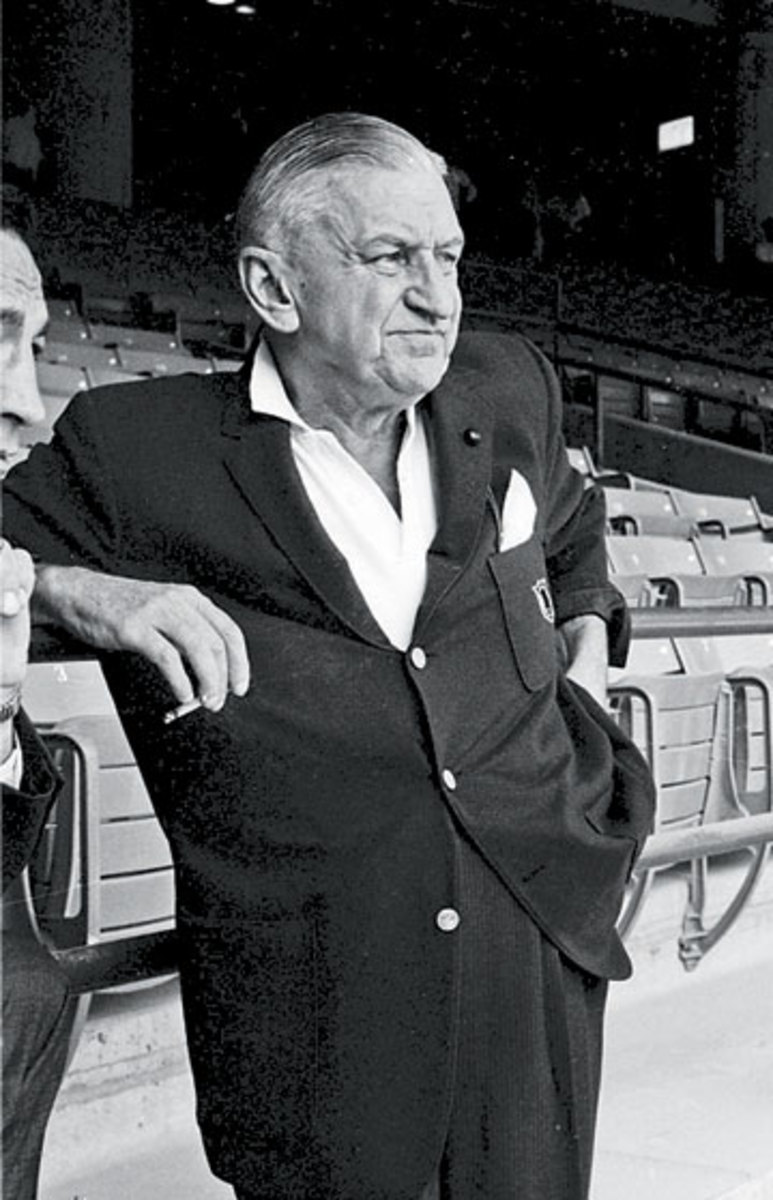

There’s an inconsistency in the story that the Washington team name was adopted to honor Native Americans. In 1933, when the franchise switched from “Braves” to “Redskins” to avoid confusion with the Boston Braves baseball team, the team had a Native American coach, Lone Star Dietz, and several Native American players. But team owner George Preston Marshall told the Associated Press at the time of the change that their presence “has not, as may be suspected, inspired me to select the name Redskins.”

George Preston Marshall. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

Snyder, who grew up attending games at RFK Stadium with his father, has not budged from his stance on the name. And he has the public support of Goodell. At the league meetings last week in Florida, the commissioner said it was "very clear when you look at public opinion, when you look at the polls, that 90 percent of Redskins fans support the name. They believe it’s something that represents pride. And the general population also supports it overwhelmingly."

Furthermore, there’s no recourse or precedent for the league or other owners to dictate what happens with the name—the decision rests entirely with Snyder. People around the league see his stance like this: Absent proof of a significant swing in fan opinion, he doesn’t want to change what he likes, or to take on the risk of a rebranding.

Ken Meringolo, managing editor of the popular blog Hogs Haven, considers the Washington team to be sacrosanct, but he admits the issue is complicated among fans. “Look, no Redskins fan thinks of himself or herself as racist,” he says. “You love this team, and the last thing you would ever want is for something you love to be negative.” He was surprised last fall when the site partnered with the Washington Post on a contest for graphic designers to submit new logos and names. They received nearly 2,000 entries, and most of the feedback was not negative. “It showed a willing participation in being a part of a new chapter,” he says.

Snyder has softened his tone a bit regarding the naming issue. Last May, he made some among the Washington fan base and in the NFL alike cringe by telling USA Today he will “NEVER—you can use caps” change the 81-year old moniker. In his letter last week he wrote that Native Americans “have genuine issues they truly are worried about, and our team’s name is not one of them.”

As with the American population as a whole, different tribal communities have different priorities. The Onondaga Nation spent eight years fighting for 4,000 square miles of land it says New York illegally obtained 200 years ago. Says Sid Hill, the spiritual leader of the Onondagas, “Land rights are our number one priority, first and foremost; it’s always on the docket. And then there are tax issues, environmental issues, passport issues, health issues. Yet somehow the ‘Redskins’ mascot keeps coming up. Is it a priority for us? No. But it always seems to enter into the conversation.”

Part of the reason is that, for those against the name, conversations about Native Americans’ rights and how their voices are represented draw on the same matters at the heart of the mascot debate. Chad Smith, the former principal chief of Cherokee Nation, says it’s a “daily fight” to ensure that rights guaranteed long ago in treaties with the U.S. are upheld. The San Carlos Apache, for example, have been engaged in a fight against a proposed copper mine that could threaten a sacred tribal site. “The mascot issue is a symptom of a lot of the problems in Indian Country,” Smith says. “The American public sees Indians as a novelty, rather than as a real people, and that penetrates other issues.”

Miles, the artist, used to work as a youth counselor in San Carlos. But when he witnessed the impact of stereotypes like the Lone Ranger’s Tonto and the Washington mascot on the self-worth of the kids under his care, he turned to art and started a skateboard company and team, Apache Skateboards, that promotes cultural pride. His “What Tribe” art campaign has staged shows in Phoenix, Los Angeles and Denver and has an Instagram account with more than 1,000 followers.

Voices

Frank Cloutier, a representative for the Saginaw Chippewa Nation in Michigan: “There are some who feel an out-and-out ban on Native American mascot images, monikers and/or the like would be the only solution once and for all. Personally I believe we should approach this issue with an optimistic spirit. This is a great opportunity to look at educational possibilities and perhaps a greater understanding of our true history here in America.”

Zandra Wilson, Navajo, cultural interpreter for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.: “A lot of times, people come into the museum and ask me what I think, and I can only share my individual viewpoint. I try to tell them I love watching football. It’s a family tradition. But I’m not sure if ‘honoring’ is the most appropriate word to be using at a Sunday football game. In some cases, I’ve felt uncomfortable. I don’t know the right way to say it—I feel embarrassed. Each feather [in a headdress] was an accomplishment, not something taken lightly. The headdresses are not made yourself; they are given to you or made for you. And achievements are not light. Do not take traditional clothing lightly.”

* * *

This issue is not new. The NCAI has campaigned against Native American stereotypes in pop culture since 1968. Arvina Martin, 34, chair of the American Indian caucus of Wisconsin’s Democratic Party, testified at a hearing for a bill opposing Native American mascots in schools when she was a high-schooler. But there is a new momentum, and times are changing. Says Martin, a member of the Ho-Chunk Tribe, “We are perfectly capable of being politically active on more than one front. Part of it is that this is one that people choose to listen to.”

The team privately believes the current groundswell has been driven in part by the media and non-Native Americans. Both groups have advanced the conversation, but Native American communities have also developed a stronger voice thanks to growing access to social media and a more vocal younger generation. “Tribal leaders across America are bigger economic partners, more sophisticated organizations than they were 20 or 30 years ago when the last attempt was made to change this,” U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell, a Democrat from the state of Washington, said in an interview with The MMQB in March. She is the former chairwoman of the Senate’s Indian Affairs Committee. “They are more able to communicate about why this is so offensive, and I think that will be a turning point in the debate.”

Sen. Maria Cantwell of Washington state, who is working with her constituents in opposition to the team name. (Charles Dharapak/AP)

Cantwell, whose constituency includes a large Native population, has been a political ally for critics of the name. In December she organized a meeting attended by Goodell and Native American leaders in Washington, D.C. But after seeing Goodell’s continued support of the name at his Super Bowl press conference and in a Feb. 27 response to a letter Cantwell sent him, she has set to work challenging the league’s tax-exempt status. “Using a slur on the field is bad, but using it on a banner above the field is somehow OK?” Cantwell says. “Because they continue to perpetrate that lie, we are going to continue to push on legislation here.”

Her plan dovetails with a sweeping tax-reform proposal by U.S. Rep. Dave Camp, a Republican from Michigan, which includes ending the tax-exempt status of professional sports leagues. (NFL teams pay taxes on the billions of revenue earned, but the league office, which is organized as an industry association, is tax-exempt.) Camp's proposal has found little support in Congress so far, but a tax restructure could affect clubs with stadium loans from the NFL.

Both sides of the debate are also awaiting the ruling of the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board, which more than a year ago heard a suit by Native Americans to cancel the registration of the team’s “Redskins” trademarks. Jesse Witten, lead attorney for the plaintiffs, says there have been at least a dozen cases since 1992 in which the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office refused to register trademarks using the word “redskins” on grounds that it may disparage Native Americans. Seven of those applications were submitted by Pro-Football, Inc., the corporation that operates the Washington NFL team, and one was by NFL Properties, Inc., the merchandising and licensing arm of the NFL.

Challenging the existing marks is more difficult, because the plaintiffs must prove that each of the team’s six “Redskins” trademarks—granted between 1967 and 1990—was disparaging to a substantial population of Native Americans at the time it was registered. In a similar suit brought in the 1990s, the Board cancelled registration of these six trademarks. But when the team appealed, a federal district court overturned the decision on two grounds: The Board lacked substantial evidence for its decision, and the petitioners waited too long to pursue their claim. In the current case, the plaintiffs are younger—closer to the age of 18 when they filed—so the second defense should not apply. Another difference is that this case would go to a different federal court on appeal, because of a reorganization since the last suit.

The trademark case could take several years to play out in a courtroom, and a related bill proposed in Congress has not yet had much support. The team could still use the “Redskins” name if its trademark registration is canceled but would have a harder time preventing trademark infringers from selling knockoff team gear.

Says Pata, “When the moral issue, the ethical issue of this, hits the purse strings, that’s when it will make a difference.” She believes Snyder’s recent outreach is, in part, a way of addressing the anticipation for the trademark board’s ruling.

Voices

Robert McDonald, spokesperson for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes in Montana: “We look forward to a day when all professional sports teams use names that bring people together rather than repelling potential fans.”

John Bush, Ph.D. in education, Vice Chair of the San Carlos Apache Tribe: “We need to get the public support to eventually not attend a Redskins game that has real negative connotations to human beings and people. If most people would research, they would understand it’s very negative, and maybe they would take a different approach to attending these games. I just can’t believe these racial stereotypes of Native Americans exist in this time and age. It’s about time the Washington Redskins owner and organization makes the change.”

* * *

Douglas Miles’s Apache skateboards. (Jenny Vrentas)

This name-change debate is a bit like the old paradox of physics: What happens when an immovable object meets an unstoppable force? Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, a Democrat from Nevada, weighed in boldly last week, telling the Washington Post he thinks the name will be changed within three years.

Snyder has already given his response to the growing pressure for a name change, and that response was last week’s announcement. To many, it’s an answer to a different question. “A paltry attempt to buy your way out of an ugly situation,” says Smith, the former Cherokee leader. “It suggests to me it may take another generation for them to come to their senses. It tells me it’s going to take more time.”

Maybe not. By now, opponents of the name are not expecting the change to be initiated by Snyder and the team, but rather through external pressures—the trademark case, legislation or public resistance. In the meantime, the calls are getting louder. “He’s clearly made sure that we all understand he’s grounded in his decision,” Pata says of Snyder. “But it doesn’t change [our optimism] at all. I think a change will be made in the near future. There is not even a doubt in my mind. I just do not think this can continue to be tolerated. This is not America, and it defies not just the first Americans, but who we are as American people, to be disrespectful to other people.”

Perhaps the most relevant question is not if there is a consensus among the country’s more than 5 million Native Americans—the answer is no—but rather, should a name change depend on one?

Robert Klemko contributed reporting from Big Cypress Indian Reservation.