Real Fantasy Football

FLOWERY BRANCH, Ga. — Christopher Peoples was easy to miss. Too easy. He bounced between two Division II colleges, averaged 293 receiving yards a season and was barely a lock to play on Saturdays, let alone Sundays.

Still, the brother had potential. North Carolina and Wake Forest saw plenty in the 6-3, 195-pounder coming out of Mooresville (N.C.) High, where his legend as a rebound-grabbing swingman on the hardwood and a redzone-scoring tight end preceded him on the recruiting trail. With a stronger effort in the classroom—who knows?—he might have scored an ACC scholarship. Instead, Peoples washed up at Livingstone, a historically black college in Salisbury, N.C., where he played in front of no more than 2,000 fans and definitely no TV cameras. The last time the school had a player drafted—tailback Wilmont Perry, a fifth-round selection of the Saints—was in 1998. He was out of the league by season three.

Witnesses under federal protection get more exposure than football players at Livingstone. And yet most there figured it would only be a matter of time before Peoples broke cover. Former Blue Bears coach Lamonte Massie had a grand vision of molding him into a road grader in the running game. (“Blocking was his forte,” Massie says.) But that project was backburnered for one more pressing—winning a measly game. Sliding Peoples over to receiver, where he could box out smurfy defensive backs, seemed like the surest way to do so. Peoples did well enough, leading the team in catches (28), yards (464) and touchdowns (five) as a redshirt freshman in 2008. But the Bears couldn’t capitalize, going 2-8 that season and 0-10 the next. In 2010 Peoples transferred to Catawba, five minutes down the road. In his final season, which never triggered a blip on Mel Kiper Jr.’s radar, he caught 91 yards worth of balls in seven appearances.

The NFL? That looked more like a goal for the next life. And Peoples might’ve given up on a pro career if he weren’t such a stickler about finishing everything he starts. What’s more, he was fueled by the many strangers he ran into at the mall or at the gym who, upon sizing him up, always asked which team he played for. Two failed post-grad auditions with CFL teams only steeled his resolve. Peoples trained after work, played semi-pro ball on the weekends on his high school field, and treated his weekly NFL TV vigils like mandatory film study sessions. “I wasn’t going to stop until I got my look,” he says.

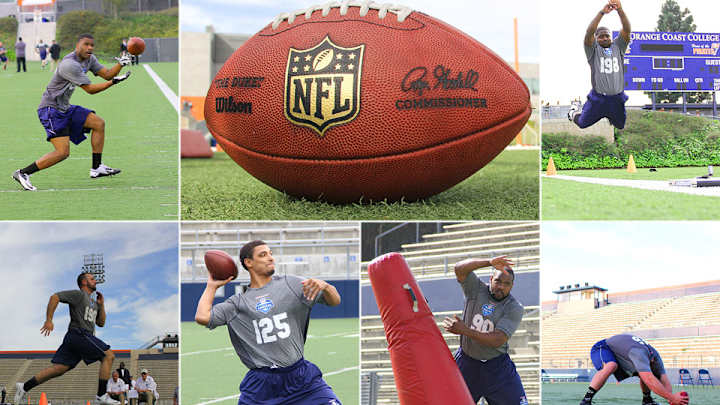

Former Catawba QB Steve Williams (l.) and wideout Christopher Peoples on the Saturday of the Atlanta regional combine. (Courtesy photo)

It was only after seeing a TV news item about the NFL regional scouting combine—a series of weekend tryouts throughout the country during the winter and spring months, culminating in a super casting call at Ford Field this Saturday—that the 27-year-old realized he could end his protracted game of hide-and-seek with the league’s talent evaluators for the low, low price of $245. He could get right in their faces, which he did on a Saturday afternoon in early March at the Falcons’ headquarters.

On Friday evening, after wrapping up an 8-to-4 shift at a group home where he works with autistic children, Peoples drove four hours from Mooresville, N.C., to the Atlanta suburb of Rex. There he crashed with an old teammate, Livingstone signal caller Steve Williams. The three years that had passed since quarterback and receiver last connected never came up when Peoples called looking for shelter.

“I’m chasing the dream,” he explained.

“I got you,” Williams said.

When Peoples showed up on his doorstep, Williams could scarcely believe his go-to guy was not only 272 pounds, but chiseled. That night they relived old war stories over tilapia and veggies. In the morning they loaded up on French toast and chicken sausage before heading their separate ways—Williams to a local park to throw to his own semi-pro teammates, and Peoples to the Falcons’ indoor practice field to pitch himself as the Hope Diamond of hidden gems.

“I always told myself that if I ever got in front of scouts, they’d give me a shot,” he says.

* * *

But first, they’d have to pick him out of among the 480 prospects who converged on the regional combine. They represented 110 colleges, including five two-year schools, four Alabamas (State, A&M, North and West), and the Art Institute of Atlanta. Some of the players sell real estate, some deliver packages, and some—of course—dabble in security. If there’s a tie that binds, it’s tension.

The line for People’s 12:30 p.m. check-in stretched from the near sideline to the parking lot. The lines at the other combines are just as long. This year 10 NFL teams (and L.A.’s Orange Coast College) crammed 20 workouts into eight weekends, drawing a total of 3,300 players—230 of whom are invited to Detroit. It’s a high-stakes game, but not just for those on the outside looking in. This is a scout’s time to step up, too. He’s under pressure—but not in the same way as when he’s evaluating a first-round talent, where the guaranteed money makes the risk exponentially higher. His reputation is still on the line.

The scout who gets a top-15 pick right is merely doing his job; the one who doesn’t will soon be looking for work. But the scout who finds a Pro Bowler disguised as a seventh-rounder or a free agent off the street—which, by the way, is exactly the kind of bargain these events are meant to uncover? He is not standing around on some field and counting down the days to retirement in five-second bursts. He is searching for the prospect that aligns with a vision in his mind, like Alfred Hitchcock walking into his silhouette. He foretells the Pro Bowl seasons that the taller-than-typical cornerback had yet to play, and the Super Bowl titles that the shorter-than-ideal QB can reach.

The regional combines offer a chance to keep chasing the dream, or if strivers don’t measure up, the push to get on with their lives. It’s closure, but with dignity.

He elevates scouting from a game of chance to a sacred art form. He takes as his reward something far greater than job security, a front-office promotion, or even a lifetime pass on every bust he stares down in the pro days to come: the license to take credit for the career of a gridiron great who came out of nowhere. If bragging rights came with merit badges, this would be football’s version of a CIA commendation—a jock strap medal.

Ron Hill wears his proudly. More than two decades ago, while visiting Division II Savannah State as a scout with the Broncos, he got a gut feeling about a young receiver named Shannon Sharpe. “People didn’t know if he was a wideout or a tight end,” Hill says. “But I had a second-round grade on him. We know the end of that story.” In 1990 the Broncos drafted Sharpe in the seventh round and slotted him at tight end. He played 14 seasons, was named to eight Pro Bowls, won three Super Bowls (two with Denver and another with Baltimore) and set the tight end standard for catches (815), yards (10,060) and touchdowns (62) in a career—though those marks have long since been surpassed by Tony Gonzalez. In August 2011, “we put Sharpe in the Hall of Fame,” says Hill, now the league’s vice president of football operations and a regional combine overseer.

This is why a scout rises in the predawn to catch a red-eye flight, holes up in his hotel room well past happy hour to finish a ream of reports, and blows off his family for months at a time—most notably on holidays: to write himself into another man’s story.

* * *

All the while, players such as Christopher Peoples have been trying to write themselves into a scout’s notebook. Before the NFL combine became so exclusive (the guest list is kept to 335) and the regional combines formalized the walk-on process by holding tryouts at NFL facilities, the vetting process was more casual.

The few teams that held open casting calls did so mainly for the publicity. The Cowboys, though, had the opposite problem. Back in the 1970s they would receive 50 letters a week from fans asking for a tryout. So in 1977 they hosted one at Texas Stadium, and were stunned when 1,800 people showed up. “They were from 38 states,” recalls Gil Brandt, the longtime Cowboys vice president of player personnel. “They came on motorcycles, by bus, by plane, by train—everything.”

The trip to Irving was longer than the stay. If a prospect didn’t fall within certain height-weight parameters, or if he didn’t run fast enough, jump high enough or kick well enough on his first few attempts, he wasn’t sent along to the next station. He was dismissed, usually with Brandt or ace scout Bob Griffin handing them a participation certificate and bidding them adieu with some version of, “Thanks for coming out, but you’re just not good enough.” The retort was always the same: “Well, can I come back again next year?”

Real Fantasy Football

A seventh-round pick in 1990, Shannon Sharpe is a three-time Super Bowl winner who was enshrined in Canton in 2011. (Damian Strohmeyer/Sports Illustrated)

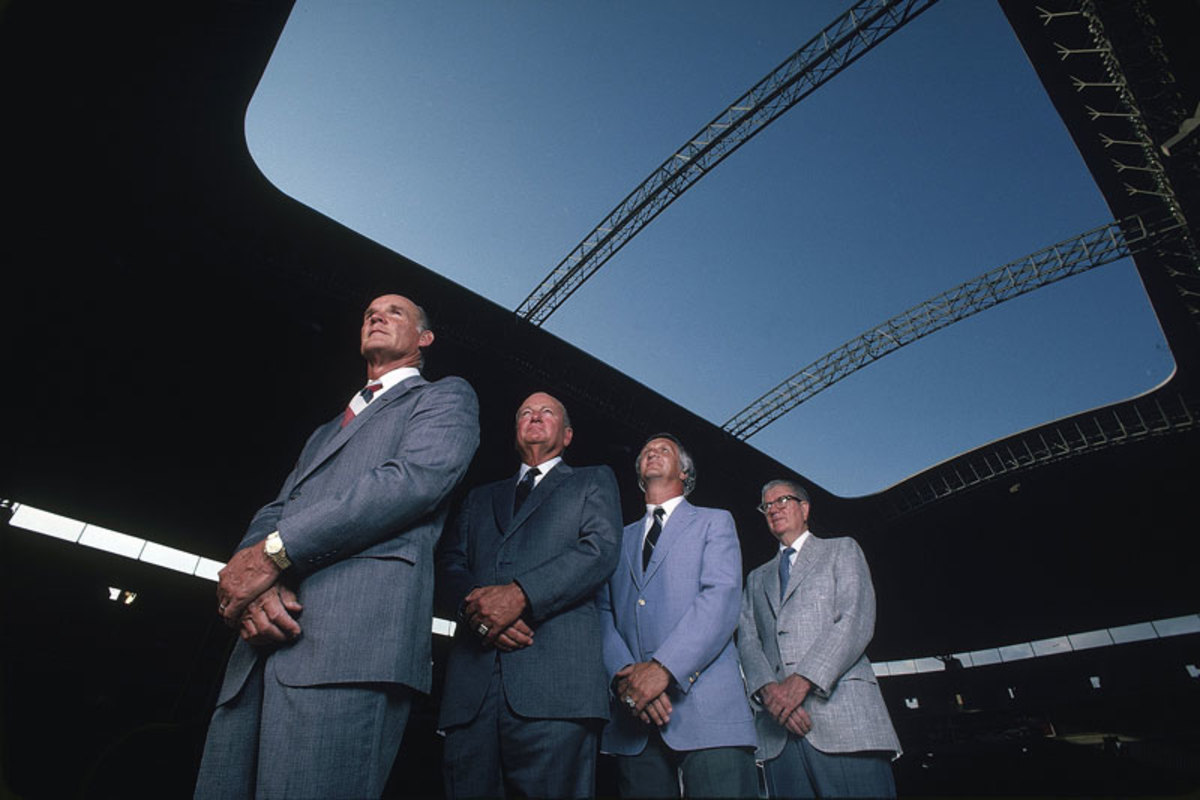

From l. to r., Cowboys coach Tom Landry, GM Tex Schramm, vice president of player personnel Gil Brandt and owner Clint Murchison at Texas Stadium in 1982. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

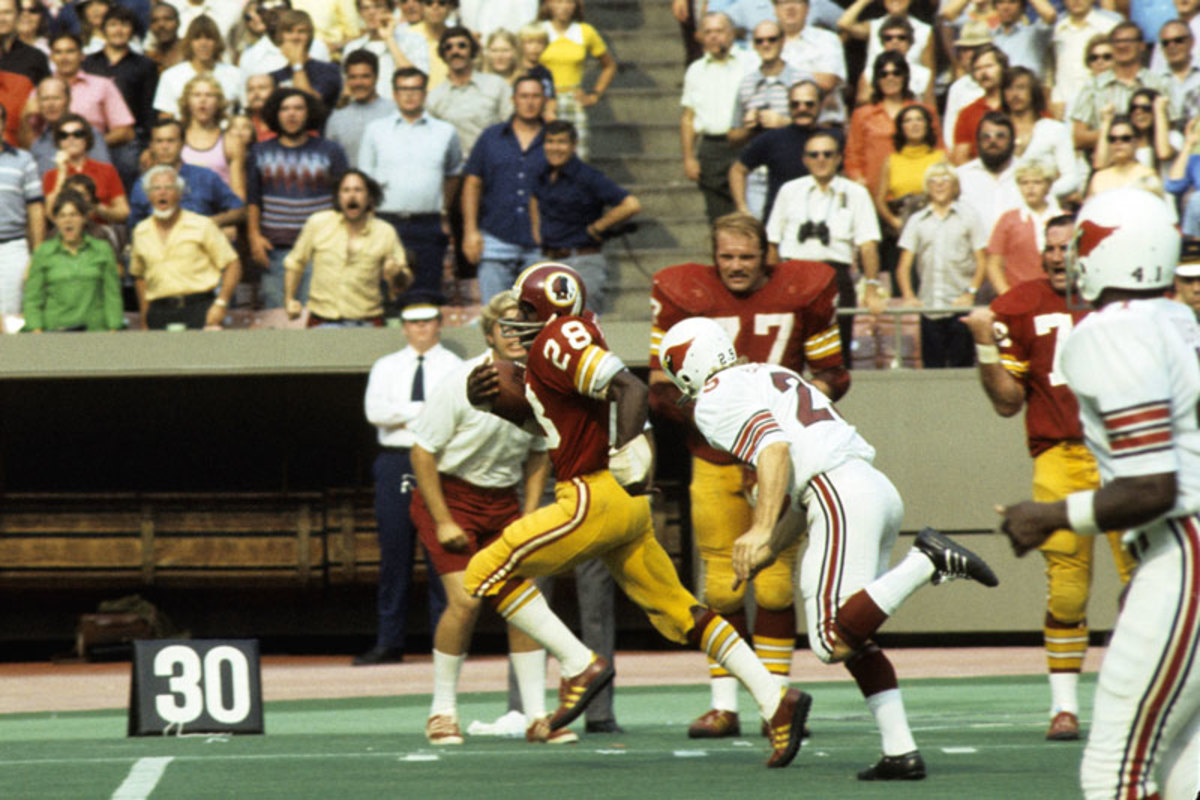

Otis Sistrunk takes down Vikings quarterback Fran Tarkenton in Super Bowl XI. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

Sistrunk recovers a fumble in the AFC playoffs against the Steelers on Jan. 4, 1976. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

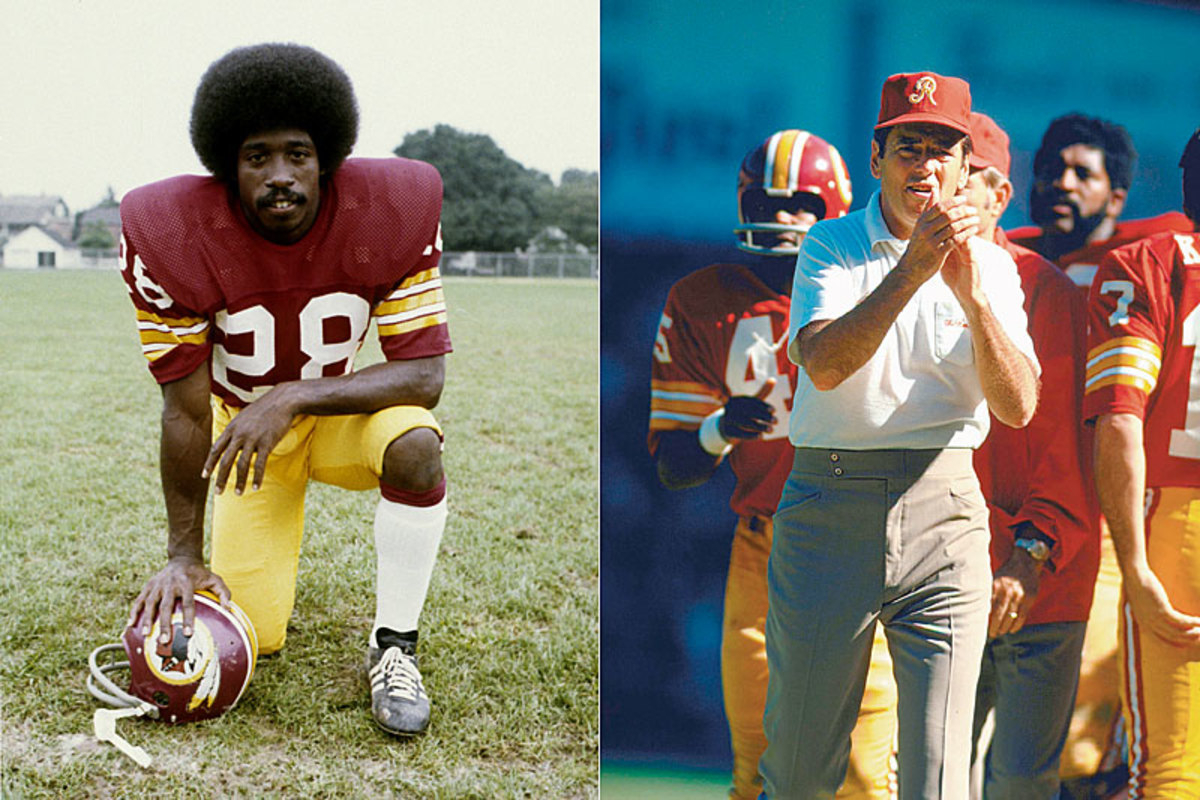

Herb Mul-Key (l.) was discovered by Washington coach George Allen at an open tryout in 1972. (NFL/Wireimage.com and Neil Leifer/Sports Illustated)

Mul-Key takes a kickoff back 97 yards for a TD against the St. Louis Cardinals on Sept. 23, 1973. (Herbert Weitman/Wireimage.com)

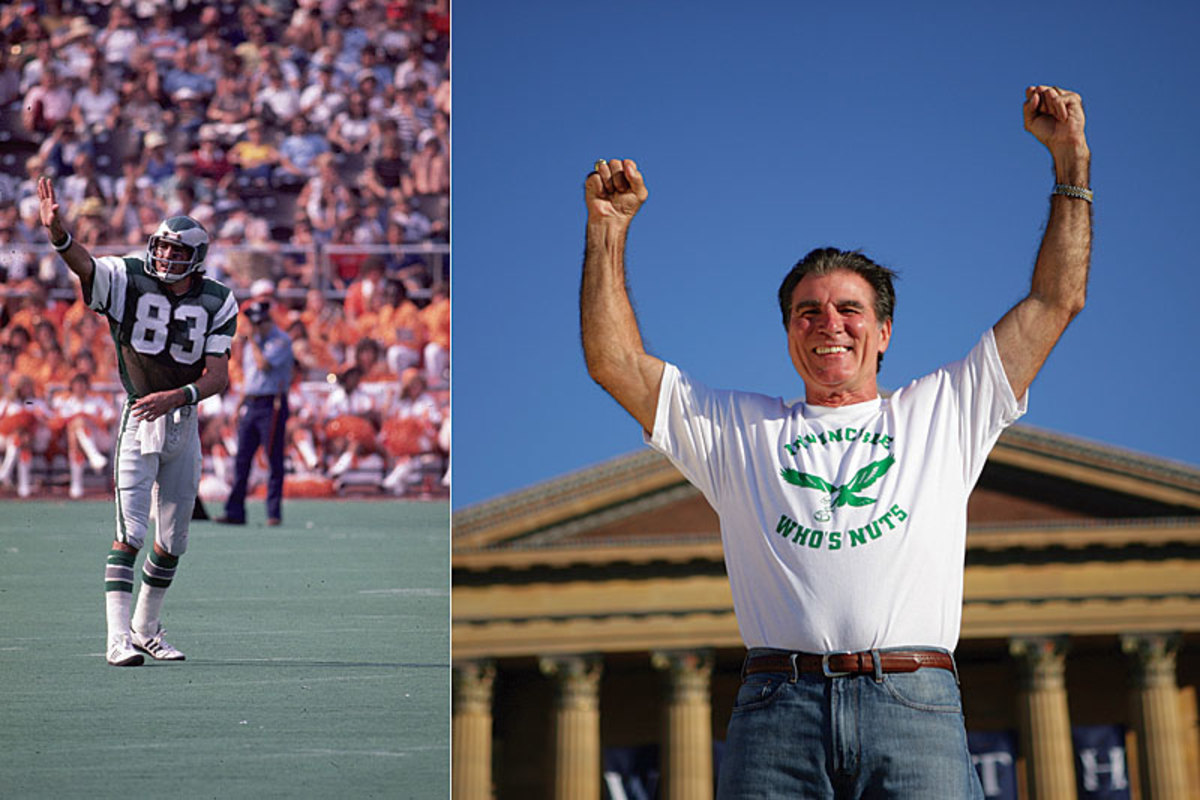

Vince Papale was a special teams standout for the Eagles in the mid-70s whose story would become a Disney movie. (James Drake and Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated)

The answer eventually became a firm no—which was fine by most prospects who weren’t so much looking for a roster spot as an authenticated story that might impress a woman. After the Cowboys let the one promising player who emerged from their tryouts—Shane Nelson, a 6-1, 226-pound linebacker out of Baylor—sign with Buffalo, Dallas’ attempt at staging a shells-and-spikes version of The Gong Show seemed like a megaflop compared to the productions George Allen had directed years earlier while the coach at Washington.

Allen’s first open tryouts at Georgetown in 1971 uncovered Otis Sistrunk, a 6-foot-4, 253-pound ex-Marine turned defensive linemen. However the coach, fabled for his Capitol-sized paranoia, was too spooked by his own silhouette to fully appreciate Sistrunk’s. So he was cut in training camp and picked up by Oakland, where he earned a Pro Bowl nod and won a Super Bowl.

A year later Allen happened across Herb Mul-Key, a 5-foot-10, 180-pound Navy serviceman who, upon hearing of the “free agent camp” from close friend Harold McLinton, a Washington linebacker, borrowed money to fly up from Atlanta to compete with some 300 other no-names. Mul-Key was a newcomer to organized football when he auditioned for the maroon and gold. Sprinting on a muddy field the Hoyas had torn up the night before, he ran a blazing 4.35 seconds in the 40-yard dash on his first try. On his second he ran a 4.36. Mul-Key was quickly signed, though he lasted only three seasons in the NFL. Still, he made the most of his brief time as a return ace, playing on Washington’s Super Bowl XII team as a rookie and reaching the Pro Bowl in ’73.

Walt Disney Pictures/Buena Vista Pictures

Just as significant as his career 27.9-yard kick return average was the impact he had on another athletically inclined everyman—a 6-foot-2, 195-pound schoolteacher named Vince Papale from Delaware County, Pa. Inspired by Mul-Key’s story, Papale—who, at 30, was almost a decade older than the walk-ons who preceded him—answered the Eagles’ casting call in 1976. Racing on the decidedly more consistent AstroTurf at Veterans Stadium, Papale clocked a 4.5 in the 40—slower than Mul-Key, but fast enough to hack it as a wideout and a special teams dynamo. And yet it wasn’t just his wheels that impressed coach Dick Vermeil.

“He felt that I glided, even though I thought I was busting my ass,” Papale says. “But he also wanted to make sure I could equate the speed with three other things: football intelligence, toughness and the ability to catch. When I combined all three, he picked me right out of the pack.”

Papale became the oldest non-kicker rookie to play in an NFL game without college football experience. Over time his 44-game run—which spanned three seasons and saw him lead the Eagles in special teams tackles (27) and forced fumbles (one) as a rookie in ’76, and make captain the following year—became such a resonant allegory for triumph that, in 2006, Disney made a movie based on his breakthrough called Invincible. And once Disney says something is possible, a whole lot more people start believing in the fairy tale.

The film’s impact could not have been more obvious at the regional combine in Atlanta. Playing the Mark Wahlberg role in their own biopics, the prospects flocked to Flowery Branch in pursuit of their Hollywood ending—including 137 to the Saturday afternoon offense-only session in which Peoples performed. “When I saw that movie,” he says, “maaaaan... ”

* * *

By 1 p.m., the offensive prospects were huddled at midfield, each down on one knee and wearing a gray T-shirt with the NFL’s shield emblazoned across their sternums. They were told to stick with their position group (designated by the tiny number scrawled inside their actual number in magic marker), to tuck in those jerseys and, by gum, to refrain from speaking to scouts. Cell phones were to be stowed until the last midfield breakdown, some six hours off. Potential litterbugs were threatened with getting a checkmark next to their name. “You may think I’m kidding around. I’m not,” said regional combine director Stephen Austen, waving a roster sheet in his hand. “You’re being evaluated at all times.” As he tore through his talking points, men with boom mikes and cameras slung over their shoulders orbited him like an electron constellation. Their footage was targeted for three shows: NFL Network’s Total Access live daily news show, a first-person story for NFL.com, and a documentary series—Undrafted—to be aired later.

A 65-year-old gale-force optimist, Austen got his start in football grinding as an agent in the ’80s, representing mostly USFL players. When a rep from the expansion San Antonio Gunslingers called pleading for bodies in 1984, Austin proposed a different idea: Instead of paying to fly down my 15 guys, why don’t you fly up and audition them here in D.C.? The rep eagerly RSVP’d “plus-two”. In the three weeks leading up to the event, word spread quickly. Austin’s 15 players told more players who told other agents who told more players. This game of telephone, which has only gotten better with email and Twitter, is why Austin still doesn’t budget for advertising to this day. “We have the population we want,” he says. On the morning of the Gunslingers workout, which, ironically, was held on a field at Gallaudet University—a school for the deaf and hard of hearing—Austin arrived to find a line of 200. That’s when he knew he had found his true career calling: the tryout business.

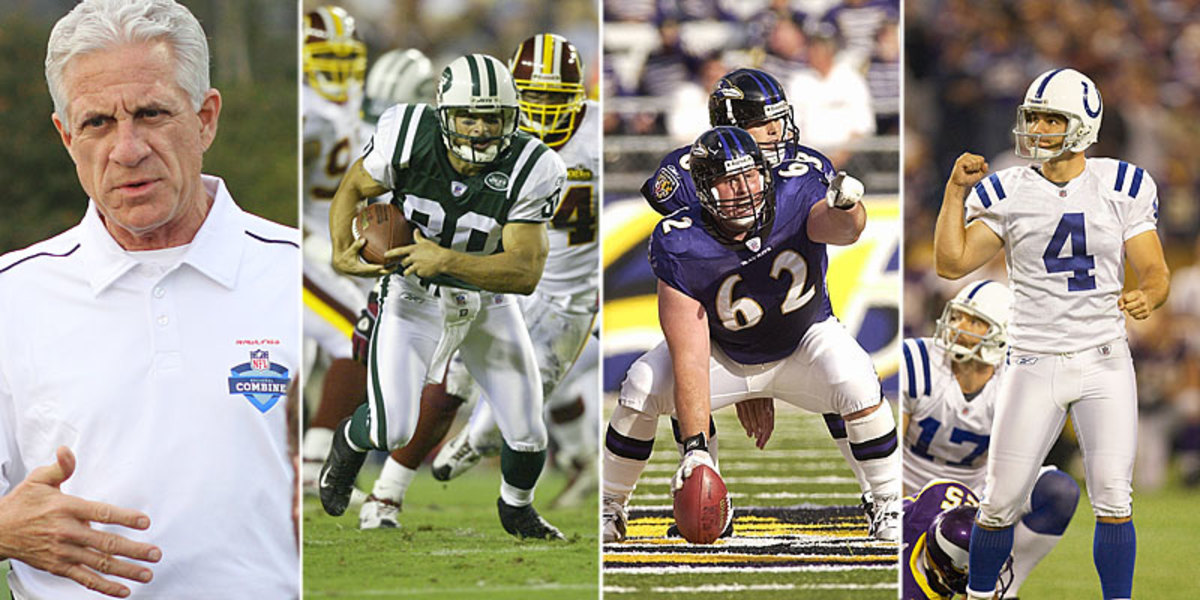

From l. to r., Stephen Austin, Wayne Chrebet, Mike Flynn and Adam Vinatieri. (Taylor W. Ashley for The MMQB; Simon Bruty/SI; Carleton Hall/Icon SMI; Damian Strohmeyer/SI)

Some of the early players who Austin discovered often scored highest on the most critical football metric—the scout’s eyeball test. A receiver out of Hofstra didn’t so much demonstrate how he ran routes as tear though them as if an imaginary Deion Sanders couldn’t keep up; that guy, Wayne Chrebet, eventually found his way to the Jets, and he remains one of the most accomplished receivers in franchise history. An offensive lineman from Maine wasn’t just thrashing blockers, but doing so with sound technique; that guy, Mike Flynn, played 10 seasons at guard and center for the Ravens and started on their Super Bowl-winning team in 2000. A South Dakota State kicker seemed to get more calm and confident the further he was pushed from the uprights; that guy, Adam Vinatieri, might end up in the Hall of Fame someday if he ever stops playing.

What Austin offers with the regional combines—which the NFL, after decades of wariness about Austin’s intentions, purchased for $3 million in 2011—is a chance to keep chasing the dream or, in the event that strivers don’t measure up, the push to get that degree, get a job, join the military and get on with their lives. It’s a rare thing: closure, but with dignity.

After a pre-workout stretch, the players scattered to the five testing stations that would measure their physical dimensions (height, weight, hand size, etc.) and athletic prowess (broad jump, short shuttle, 40-yard dash, etc.). Once all the groups had rotated through, it was on to position-specific drills with names like “Pass Pro Mirror” (in which O-lineman must shadow a rusher’s lateral movement) and “Off-Tackle Reaction” (in which a tailback must run through four step-over dummies and cut away, in either direction, from a standup dummy before ripping off a 20-yard sprint). Apart from exertive grunts, no player really makes any noise; the drill proctors, with their measured instructions, aren’t much louder.

Middle Tennessee State QB Logan Kilgore was cheered on at the Atlanta regional combine by Alabama’s AJ McCarron. (Mark Humphrey/AP)

As the program droned on into its second hour, a tall figure emerged from his seat against the wall dressed in a gray hoodie, black windbreaker pants and weathered baseball cap. This was AJ McCarron’s attempt to blend in. It didn’t work. The place was already abuzz about the presence of Alabama’s quarterback, who could go anywhere from the first to third round in this year’s draft. He’d driven down from Jackson, Miss.—11 days after the Indy combine and four days ahead of his Tuscaloosa pro day—to support Middle Tennessee State’s Logan Kilgore, a Manning Passing Academy buddy turned pre-draft workout partner. “I think he’ll show he’s the best QB out here,” McCarron said.

As one might expect, the skill levels don’t always match up at regional combines. A QB who can throw (like Kilgore) doesn’t always draw a receiver who can catch (like Peoples)—and vice versa. In this venue, a scout has to ignore the incompletions (no small task, given their frequency) and focus instead on the little things: a QB’s setup; whether a receiver waits for a pass or snatches it; the little things that are obvious on film, which prospects receive in web-link form after the workout.

For most, it is not a good look.

Antoine Morgan, a 28-year-old semi pro tailback, promised a 40-time in the low fours; he ran a 5.3. (Morgan himself is practically sub-5. At 5'1", he would be among the smallest players in NFL history.) Blake Corl-Baietti, a lightly used 28-year-old JUCO quarterback, was the day’s most tightly wound performer, alternating between frustratingly clapping his hands and shaking out his throwing arm after every effort. Making a joke of his misery becomes harder after finding out he’s pursuing an NFL career as a tribute to his father (who recently survived a devastating car accident), and then easier after discovering he was once romantically linked to Demi Moore (who, well ... so much for the idea that he’s doing this to impress women). Another QB, Isaac Jackson, wasn’t much looser; that he’s 41 doesn’t even faze him. “I feel like I’m in my mid-30s,” he says. If he doesn’t make it to the super regional this year—spoiler alert: he didn’t, nor did Morgan or Corl-Baietti—he’s going to keep gunning for it “till about age 45.”

For some, well, there may never be closure.

* * *

As a receiver at Army, Alejandro Villanueva pulled in a one-handed grab against VMI in November 2009 (left) and soared against Navy a month later. (Frank DiBrango/Icon SMI and Matt Slocum/AP)

Peoples acquitted himself well in front of nine scouts and Falcons coach Mike Smith, who could certainly use a tight end to replace the retired Gonzalez. Peoples’ 40 time wasn’t the fastest (just under five seconds), but come on: He’s 272 pounds. His vertical (31”) and broad jump (9’3”) would place him in the top 15 among tight ends who tested at the Indy combine; they put him in the top four at Atlanta’s regional combine. Just ahead of him was Alejandro Villanueva, a 25-year-old who is making up for lost time. Four years ago, as a wide receiver, he led Army in catches (34), receiving yards (522) and touchdowns (five). This was after a two-year stint as a triple-option O-lineman and a try at defensive end as a freshman. As Army experiments go, this seemed fitting given that Villanueva is 6-foot-9. Certifiably intriguing, he received a last-minute invite to the 2010 East-West Shrine game—so last minute that the official game program went to press before his name could be added. Panthers defensive line coach Sam Mills, one of the game’s guest assistants, spent the practices turning Villanueva into a tight end. His stat line (one catch, eight yards) stood out less than his overall disillusionment with big-time football. “For some [prospects], this is all they can do,” Villanueva said at the time.

And then he went off to war. To Afghanistan. During the surge. Three times. The last two as a platoon leader with the 75th Ranger Regiment—the force in which former Cardinals safety Pat Tillman was serving when he lost his life. The years went by in a blur, with no birthday or Christmastime stories to mark the passing of time. Keeping a hand in the game, as one might expect in a war zone, was a big ask. “I’d usually watch games on the Armed Forces Network,” he says. “Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes whoever’s got the remote wants to watch How I Met Your Mother. It’s pretty cool to see guys I’ve played against, either from the teams Army played or just guys I played against at the Shrine game.” He earned a ticket to Detroit’s super casting call this Saturday, but if he can’t prove he belongs, he might well have to redeploy.

Benson Mayowa putting a hit on Panthers QB Cam Newton in 2013. (Mike McCarn/AP)

The stakes aren’t as high for Shea Allard, a 24-year-old offensive line prospect who overlapped with Joe Flacco at Delaware. But that doesn’t mean he isn’t feeling the heat. He had a funny way of placing it on himself. Dissatisfied with a camp stint with the Packers last summer (which led to a forgettable few months as a Winnipeg Blue Bomber), Allard launched an internet campaign to raise $7,000 to fund trips to 10 regional scouting combines—and exceeded that goal in four months. He booked five trips and saw his production climb with each visit. When he got the news after Atlanta that he was moving on to Detroit, the moment was bittersweet. The following week’s workout in Chicago was already paid in full. Still, it was a good problem to have—and not just for him. “I decided to forfeit my spot to give another kid a shot,” says Allard, who had been on the road for six weeks and aims to repay every crowdsourced dollar with a charitable contribution to be named later. If all goes according to his plan, he’ll be tithing from an NFL paycheck.

Allard is not the first prospect to go the extra mile. Last year Benson Mayowa, a 6-3 defensive end, could barely get a pro scout to look at him coming out of Idaho, which had gone 3-21 in his final two seasons. So he traveled from Moscow, Idaho, to a regional combine in Dallas, and then to another in Seattle—“and killed it,” he says. Weeks later the Seahawks signed him to a three-year deal, and he remained on the active roster for the entire 2013 season, which culminated with a Super Bowl title. That he’d be forced to take out a few additional student loans to get that ring mattered little to him in the final analysis. “It was worth it,” he says.

* * *

For Les Snead, the value goes farther. Two years ago he was the rookie general manager of a St. Louis Rams team in critical condition. After finishing the 2011 season in a tie with Indianapolis for the NFL’s worst record, the Rams needed a talent transfusion. Special teams was the obvious area to draw first blood. The unit’s core players, kicker Josh Brown and punter Donnie Jones, had severely underachieved on expiring contracts. And with both over the age of 30, they were about to become more expensive. In particular Brown, whose 75% field-goal conversion rate was the league’s second-worst mark, was set to account for $3.7 million against the 2012 salary cap. Snead couldn’t afford to take that hit, or re-up with Jones—an impending free agent with a middling 44.3 yard punting average that failed to justify his $1.1 million salary in ’11.

Rookies, of course, were a cheap solution. But were they a good one? Specialists, after all, are the hardest prospects to get a handle on. Finding capable ones takes an even more exhausting effort than finding position players, where the talent pool is much deeper. If Snead was going to go through with this, he had to really know his market.

Greg Zuerlein looked the part; he set the Division II record for consecutive field goal makes (21) and led the entire NCAA in field goal percentage (95.2%). And he was close enough at Missouri Western State—where he transferred for his final season after Nebraska-Omaha canceled its football program—for Rams special teams coach John Fassell to perform regular checkups.

Rams GM Les Snead (far l.) scoured the regional combines to find punter John Hekker (No. 6) and kicker Greg Zuerlein. (Jeff Roberson/AP and David Welker/Getty Images)

“What we wanted to do, because he was a small school prospect, was put him in as many pressurized situations as possible,” says Snead, who began his front-office career as a scout for Atlanta. But in taking the initiative to attend a 2012 regional combine in Detroit, Zuerlein was able to show the Rams how he fared when directly competing against other college kickers, a degree of difficulty St. Louis couldn’t otherwise duplicate. When he aced that test—averaging 67.0 yards on kickoffs and making all his field goal attempts, including a pair from 55 yards away—Snead knew he had his man.

A regional in New York uncovered another curious talent—John Hekker, a prolific Oregon State punter who had traveled from Corvallis to Florham Park, N.J., to, well, wet his feet. “I wanted to see how I stacked up against the hundreds of guys who were fighting for 32 positions in the world, to see where the competition level was and how seriously guys were taking their training,” Hekker says of his first NFL workout. He didn’t have the greatest afternoon, averaging 38.7 yards per punt. By the time of Oregon State’s pro day, which Fassell flew out to conduct, Hekker had worked out all the kinks. The regional, he adds, “was something that started the fire, made things real and set me on the right track as far as getting ready for the road to the NFL.”

By the draft, Snead had enough information to make informed decisions. He picked Zuerlein in the sixth round and signed Hekker as a free agent, then cut Brown and let Jones walk. The moves paid immediate dividends. Zuerlein quickly made a name for himself as the Rams’ best offensive player in 2012 (with 95 points scored), a long-distance specialist (which earned him not one but two of the best nicknames in recent football history: Greg the Leg and Legatron) and damn near kicked a 7-8-1 team into the playoffs. Last year Hekker set the NFL single-season mark for net punting average (44.2 yards) and went to the Pro Bowl along with rookie rush end Robert Quinn—rounding out the Rams’ first multiple all-star class in eight years. This season both specialists will barely cost St. Louis a combined $1 million. For a team that has almost $27 million in cap space tied up in one player, quarterback Sam Bradford, these savings goes a long way.

The regional combines are promoted as scouting insurance for NFL teams but, really, it’s better than that. It’s more like their Carfax—consumer protection, an extra set of trusted eyes. By essentially setting the bottom half of the talent market, the tryout process does the work of 32 scouting departments, saving them time and money that can be reinvested at the top of the market. And with owners like Cincinnati’s Mike Brown a couple years removed from downsizing his scouting department to just one full-timer, the regional scouting combines could some day be a killer app. Maybe not now. “There’s probably never going to be a piece that solves the whole riddle,” Snead says. But as the combines become a better scouting supplement, the burden on assistants like Fassell could get heavier.

* * *

For Peoples, though, this particular Saturday was light work. His performance in Atlanta was strong enough to merit an invite to the super regional in Detroit—news he celebrated by punking his former QB over the phone.

“I’m calling to give you the news about the NFL,” he told Williams, doing his best Eeyore impression.

“What did they say?”

“They said—maaaaaan, I’m going to Detroit!”

He couldn’t help himself. “It was real fun to be able to mess with him,” says Peoples, who also gotcha’d his dad and a couple of other friends. Sure, Williams took it personally, but not in the way you might think. “It makes me feel better that he didn’t come down here in vain,” he says.

This weekend, though, things get serious. Representatives from all 32 teams will be in attendance at Ford Field. The stakes, compared to the last workout, will be even higher. Of the 230 invitees, about half will either be signed or drafted. And about half of those signed could find themselves on an NFL roster next season. So this is more than the look Peoples had long hoped for. This is something he can touch, a dream that’s finally within his grasp.