Artificial Turf: Change From the Ground Up

Editor’s note: This is the second in The MMQB’s 10-part series NFL 95: A History of Pro Football in 95 Objects, commemorating the 95th season of the NFL in 2014. Each Wednesday through the start of training camp in July, The MMQB will unveil one long-form piece on an artifact of particular significance to the history of the NFL, accompanied by other objects that trace the rise of professional football in America, from the NFL’s founding in a Hupmobile dealership in Canton in 1920 to its place today at the forefront of American sports and popular culture.

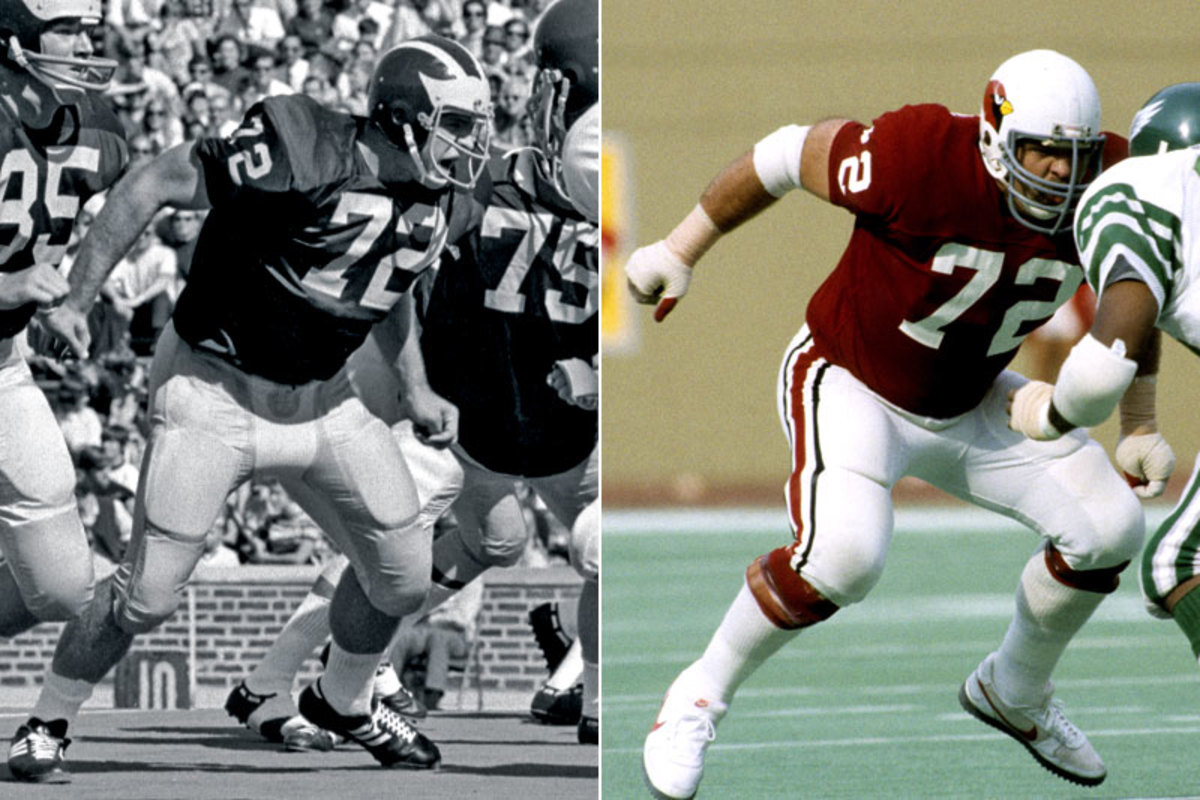

It was the summer of 1969 when they sent Dan Dierdorf out to start digging a grave for his hips, his knees and his spine. Nobody understood this at the time, least of all Dierdorf. He was a 19-year-old sophomore at the University of Michigan, a big kid from Canton, Ohio, 6-foot-3 and more than 270 pounds, and he just wanted to play football. In the previous autumn he had earned a starting position on the offensive line in the final season before Bo Schembechler took over the Wolverines from Bump Elliott, and Dierdorf wouldn’t surrender that spot for three years and 25 victories. Then he would play 13 more seasons in the NFL, all for the St. Louis Cardinals, and play so well that he would be voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, one of only 19 offensive tackles so honored. But this was before all of that.

In that summer of ’69, Dierdorf was given a job by the Michigan Athletic Department. It was authentic work—day labor for real money. Dierdorf and some other members of the football team were sent to the floor of Michigan Stadium as members of a work crew assigned to tear up the natural grass field. They ripped up sod in giant panels, loaded it onto trucks and delivered it to various grass-needy locales around Ann Arbor. When they came back to the stadium, another job awaited: Unrolling giant spools of pale green carpet to replace the grass. The new surface was called Tartan Turf, manufactured by 3M as a competitor to Monsanto’s Astroturf, which had come into use two years earlier, for use on the baseball field in the Astrodome. The Big House was among the first major football stadiums to replace natural grass with artificial turf, though the practice would become epidemic over the next several years.

After helping install the new turf at the Big House, Dierdorf played three seasons on it, and another 13 on the hard surface at Busch Stadium as a Cardinal. (Bentley Historical Library :: Herbert Weitman/WireImage.com)

By September, the Wolverines were playing games, and occasionally practicing on the Tartan Turf. And initially, Dierdorf didn’t entirely dislike it. “It tore up your skin if you fell on it,” says Dierdorf. “But as an offensive lineman, you were guaranteed to get good traction on every play. On pass plays, you really liked the fact that you could drop back and plant, and your foot was never going to slip. From that point of view, you kind of liked it. It was sticky and reliable. I never thought for a minute about what it might be doing to my body.” Dierdorf stops and returns to the more ominous truth of his present-day life: “Who knew?”

Who knew that Dierdorf, 64, would be telling this old college story four and a half decades later, in March of this year, eight weeks after he was hung upside down for 11 hours of surgery to rebuild his spinal column, aided by the insertion of three metal rods and 32 screws. Both of his knees and both of his hips had been replaced, as of six years earlier, yet his legs had withered from a tackle’s tree trunks to a distance runner’s pipe stems because of nerve damage in his spine. The back surgery had left Dierdorf 2 ½ inches taller, nearly restored to his full height after years of stooping further toward the ground, yet he would need months of physical therapy to teach himself to walk again. In January, Dierdorf retired after 31 years of broadcasting NFL games on television because his body could no longer withstand weekly air travel (he has since taken a job broadcasting Michigan games on radio; the travel is far less demanding).

A special 10-part series from The MMQB tracing pro football’s rise through the artifacts that shaped the game, with one long-form story and shorter entries every Wednesday through the start of training camp.

Week 1: Inside Steve Sabol’s office. FULL STORY

And he is certain that much of this physical damage was caused by endless hours of football on artificial turf, beginning with the first season in Ann Arbor and continuing for a decade and a half. After he left Michigan’s Tartan Turf, Dierdorf played games and also practiced four days a week on the unforgiving first-generation AstroTurf at Busch Memorial Stadium in St. Louis. When the baseball Cardinals needed to work out, the football Cards would rope off a rectangular section of outfield carpet and proceed, rather than missing a day on the rug. This went on until 1987, four years after Dierdorf’s retirement, when the Cardinals moved to Arizona and the lush natural grass of Sun Devil Stadium. “It wasn’t so much playing games on artificial turf; it was all those practices,” says Dierdorf. “If you count training camp, [it was] probably 10 practices for every one game.”

Understand, Dierdorf isn’t asking for sympathy or assigning liability (beyond his own), and he isn’t damning the game to which he gave his limbs. Quite the opposite. “Football is a tough game, and you pay a price for that,” says Dierdorf. “But I don’t want anyone to misinterpret my feelings. I love the game of football. If I could go back, I would do everything over again.

“But in hindsight,” he says, “I sometimes sit and think about how different my life would be right now if I had been drafted by the Raiders or the Chargers [both teams with natural grass fields, then and now]. I wouldn’t be the cripple that I am now. I’m not feeling sorry for myself, and I’m not blaming anyone. I just wish it was different. The Cardinals didn’t say ‘Let’s put this artificial turf in so we can cripple our players.’ For a little while, the league had a love affair with artificial turf. Who knew what was happening? Nobody knew.”

* * *

It is impossible to know with any certainty the exact role artificial turf played in Dierdorf’s—or any player’s—physical breakdown. Long-retired players suffer not just from the surface that lay beneath their feet, but from the collisions that impacted the rest of their bodies. How the blame is apportioned is anybody’s guess. Yet Dierdorf’s is the extreme version of a common narrative from players in the 1970s and ’80s. “I don’t’ know anybody who liked playing on the artificial turf that we had back then,” says ESPN analyst Herman Edwards, who spent all but one of his 10 seasons in the NFL on the notorious carpet at Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia. “It was like playing football on concrete.”

This much is not up for debate: Players disliked early turf, they dislike modern turf a little less. Nearly all of them prefer grass.

Yet the story of artificial turf’s impact on the history of the NFL is writ large and far more complex than simply damning the early version of a product that remains in wide use. “It’s been a love-hate relationship,” says Andrew McNitt, professor of soil science and director of the Center for Sports Surface Research at Penn State. “There is a traditionalist in all of us that really wants to see games played on natural grass. But in 1970, the state of the art and science of growing natural grass was way behind where it is today. Along came artificial turf. Coaches raved about how great it was. Then there was criticism. Then there was a lot of positive talk with the development of the [current] artificial turf, and now a little bit of criticism again.”

GALLERY: Tales of the Turf

Artificial Turf: Change From the Ground Up

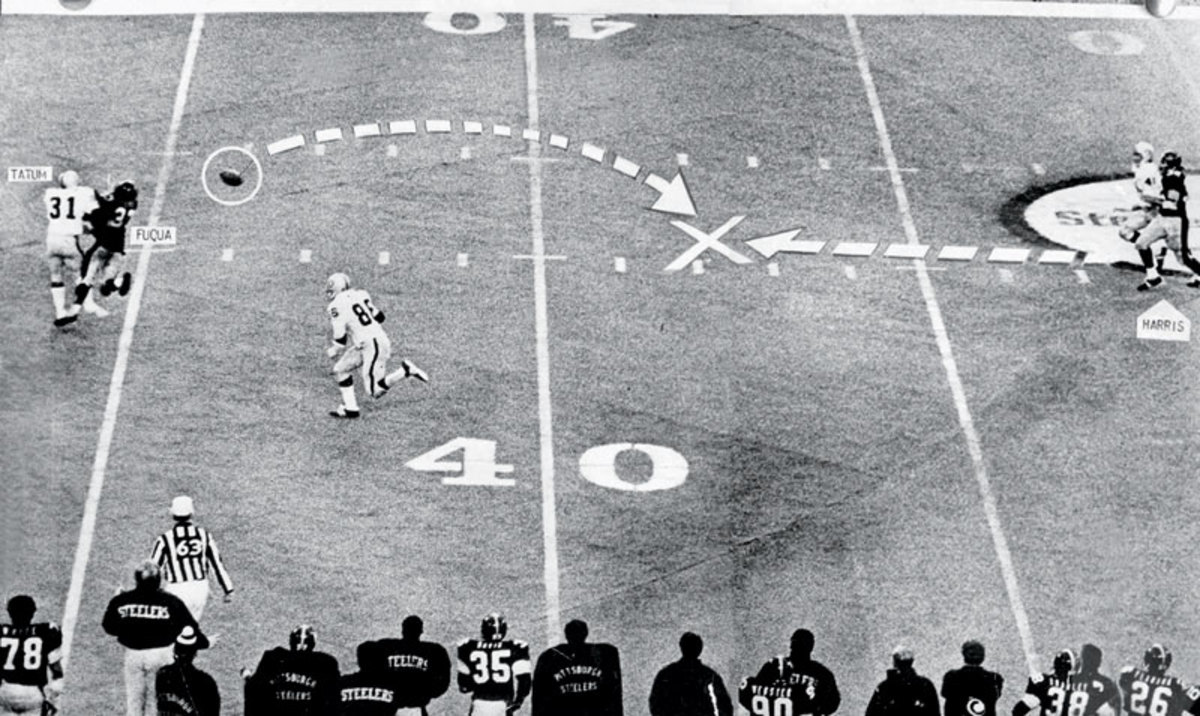

The Immaculate Reception played out just as the Steelers drew it up on the Tartan Turf at Three Rivers. (Donald J. Stetzer/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette/AP)

Larry Csonka and the Dolphins pounded their way to a perfect season on the plastic at the Orange Bowl in 1972. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

Lynn Swann stole the show in Super Bowl X, before Miami’s Orange Bowl reverted to grass. (Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated)

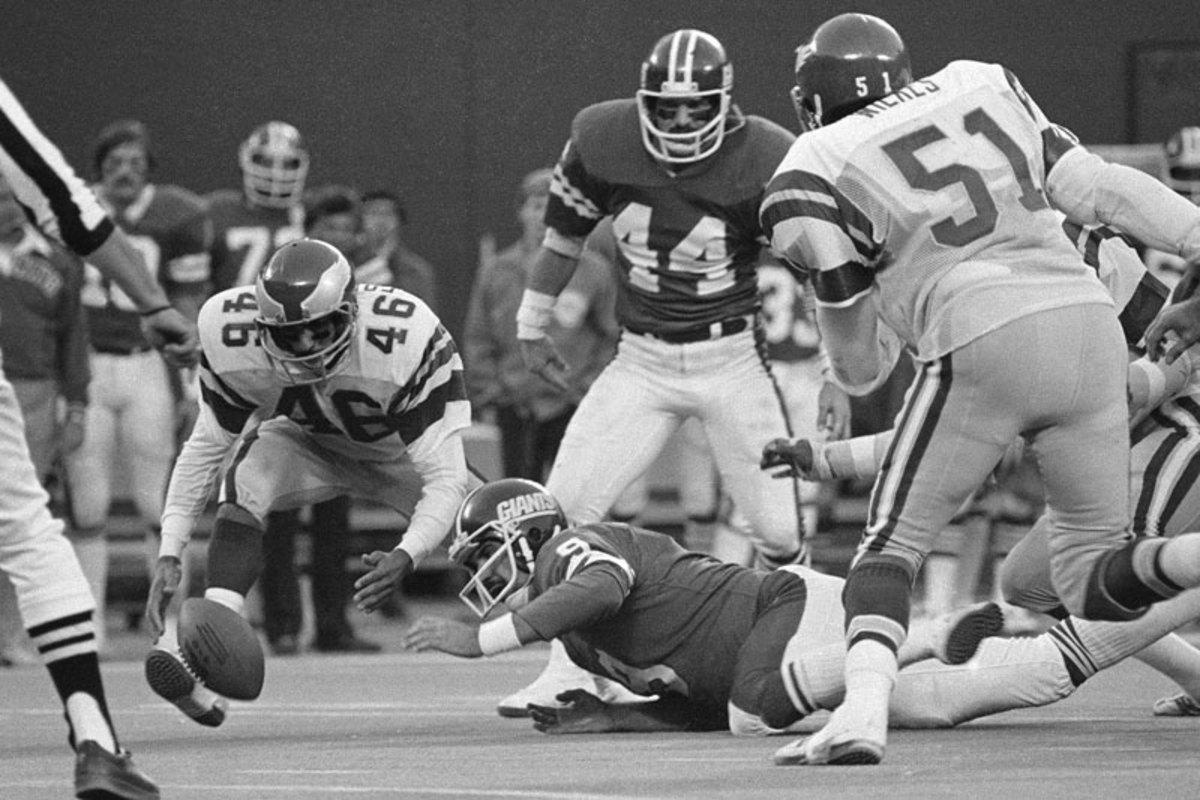

Herm Edwards (46) hated his hometown surface in Philly but got the perfect hop off the Giants Stadium turf in the Miracle at the Meadowlands. (G. Paul Burnett/AP)

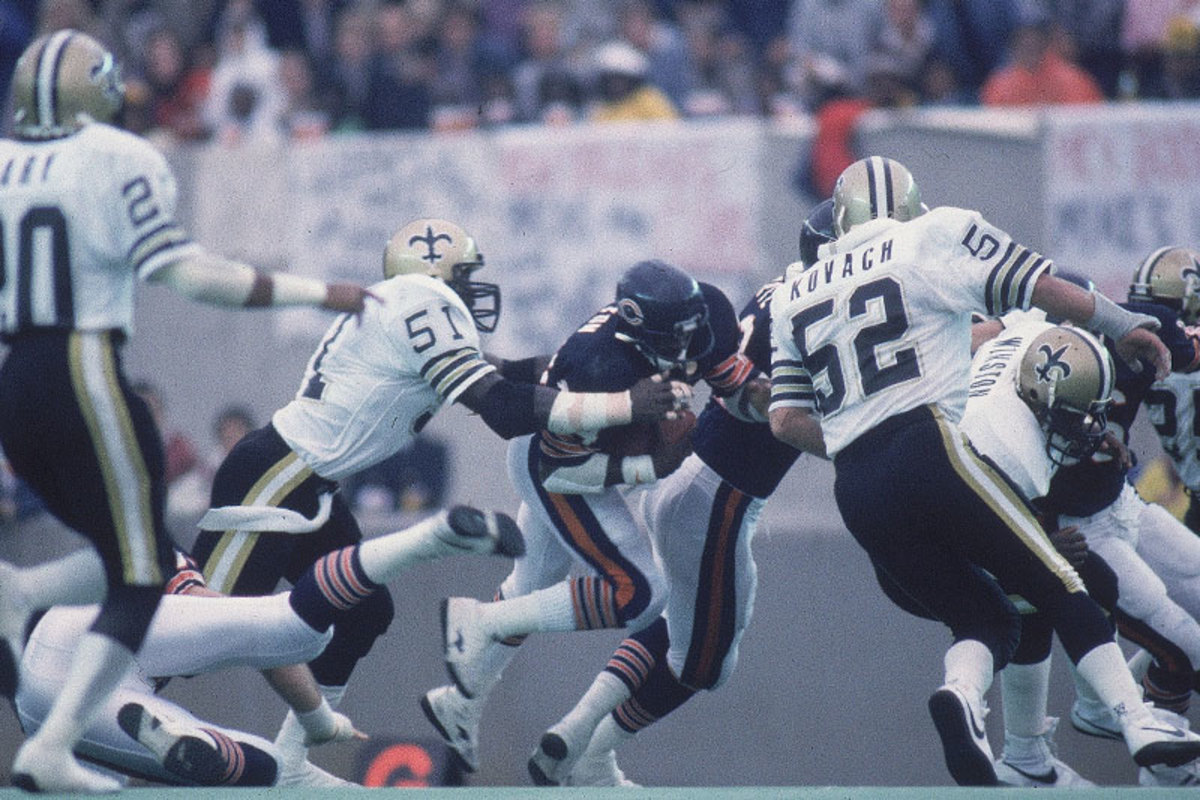

Walter Payton broke Jim Brown’s rushing record on the hardpan at Soldier Field in 1984. (Andy Hayt/Sports Illustrated)

And the Bears’ D stood its ground there through much of the ’80s. (Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated)

Lawrence Taylor turned the turf at Giants Stadium into a terror zone for opposing quarterbacks. (John Biever/Sports Illustrated)

Emmitt Smith scooted past Payton’s mark on the “RealGrass”—i.e., not real grass—at Texas Stadium in October 2002. (Bill Frakes/Sports Illustrated)

The Rams’ speed-based offense of the late ’90s and early 2000s benefited from a fast surface that allowed Marshall Faulk and his mates to cut quickly. (David E. Klutho/Sports Illustrated)

Randy Moss and the 2007 Pats found the artificial turf at Gillette, installed the previous year, conducive to scoring. (Damian Strohmeyer/Sports Illustated)

The strip of Tartan Turf on which Franco Harris completed the Immaculate Reception. (John DePetro/The MMQB :: Courtesy Pro Football Hall of Fame)

Yet in a more artistic sense, artificial turf is a canvas on which some of the most significant moments in the history of the NFL are painted and preserved forever. The undefeated 1972 Miami Dolphins played their home games on Poly-Turf in the Orange Bowl. Franco Harris plucked the Immaculate Reception off the artificial turf of Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh in December of that same season. Lynn Swann acrobatically pulled Terry Bradshaw’s passes from the Florida sky in Super Bowl X, the last football game played at the Orange Bowl before it went back to grass in 1976. Edwards picked up Joe Pisarcik’s muffed handoff at Giants Stadium in the Miracle at the Meadowlands in 1978. Lawrence Taylor implored his Giants teammate to “get out there a like a bunch of crazed dogs” on that same Meadowlands turf. Buddy Ryan’s “46” Bears ran roughshod over the NFL while playing home games on artificial turf at Soldier Field. Buffalo’s K-Gun offense, the Rams’ Greatest Show on Turf and the Patriots’ unbeaten 2007 regular season all were turf-based. Seven Super Bowls have been played on the plastic at the Superdome in New Orleans, more than any other venue.

So it’s true that the game does not always remember the rug fondly, but the rug is stitched deeply into the story of the game.

* * *

In 1964, Chemstrand, a subsidiary of the Monsanto Corporation installed a synthetic surface called Chemgrass in the fieldhouse at the Moses Brown School in Providence, R.I. It was almost coincidental that synthetic turf landed in professional football four years later. “The developers of the original synthetic turf system most probably did not envision their creation to be on the playing fields of professional sports,” wrote McNitt, Thomas J. Serensits and John C. Sorochan in a chapter devoted to artificial turf in the 2013 textbook Turfgrass: Biology, Use and Management. “After the Korean War, the Ford Foundation determined that military recruits from rural areas were in better physical condition than those from urban areas because [the latter lacked] safe, suitable places for children in cities. To address this problem, synthetic turf was developed….” (It’s impossible to miss the irony that a surface reviled by many for its punishing qualities was originally conceived for safety).

In 1966, Chemgrass was installed in the Astrodome for baseball (because the light through the roof panels, some of which were painted over to reduce glare, proved insufficient to sustain live grass) and summarily renamed AstroTurf; two years later the Houston Oilers—then a member of the AFL—moved into the Astrodome and became the first professional football team to play on artificial turf. A year later the Eagles began playing on artificial turf at venerable Franklin Field, and in the spring of 1970, NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle told a gathering of businessmen in Chicago that he expected every team in the NFL to be playing on artificial surfaces “within a few years.” The league seemed to follow his cue: Five teams went to synthetic surfaces in 1970 and five more in 1971. By the beginning of the 1976 season, 16 of the 28 teams in the NFL were playing on first-generation artificial turf of some variety, a number that would peak at 17 in the 1984 season.

GALLERY: Looking Down From the Dome

Artificial Turf: Change From the Ground Up

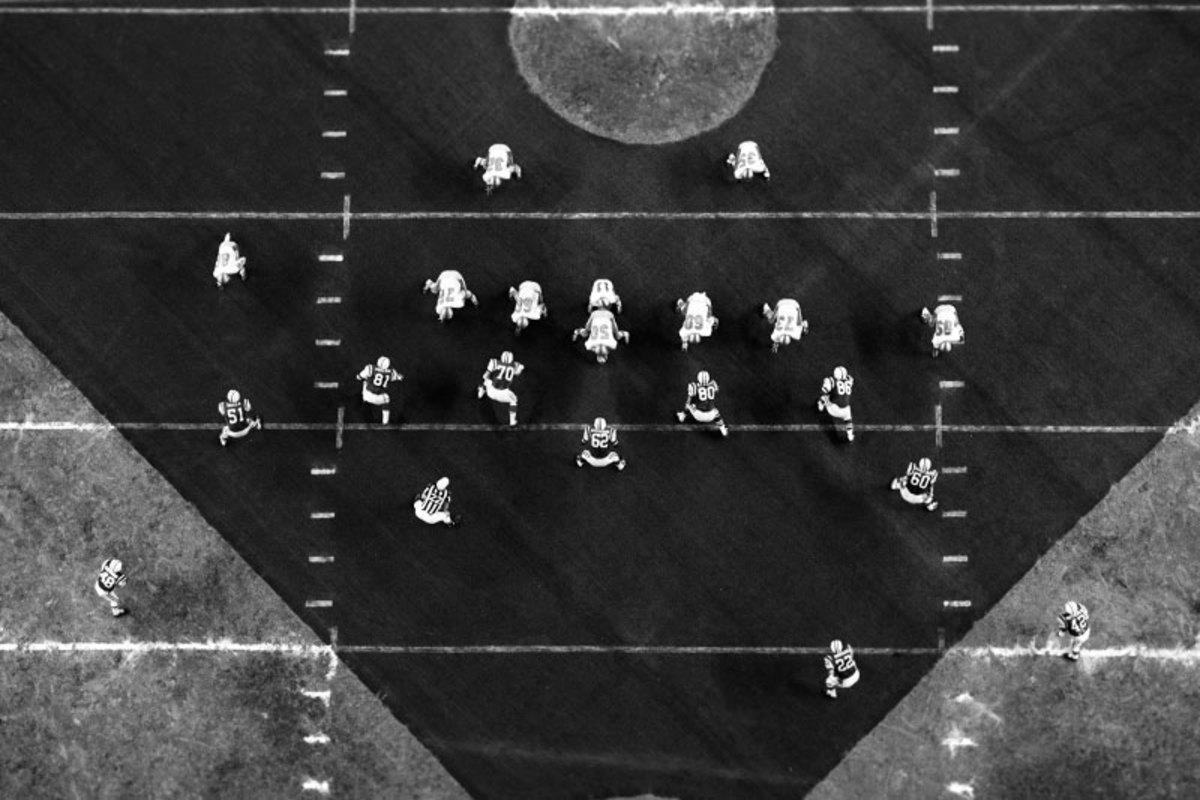

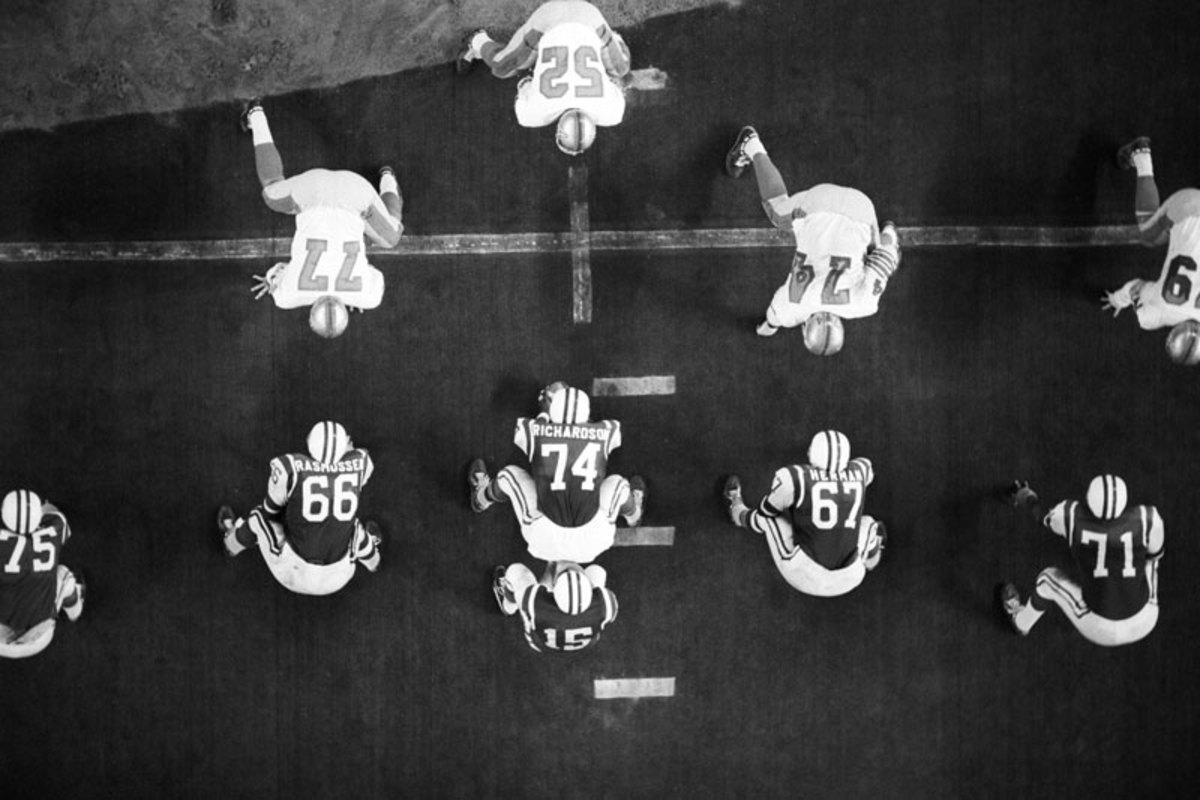

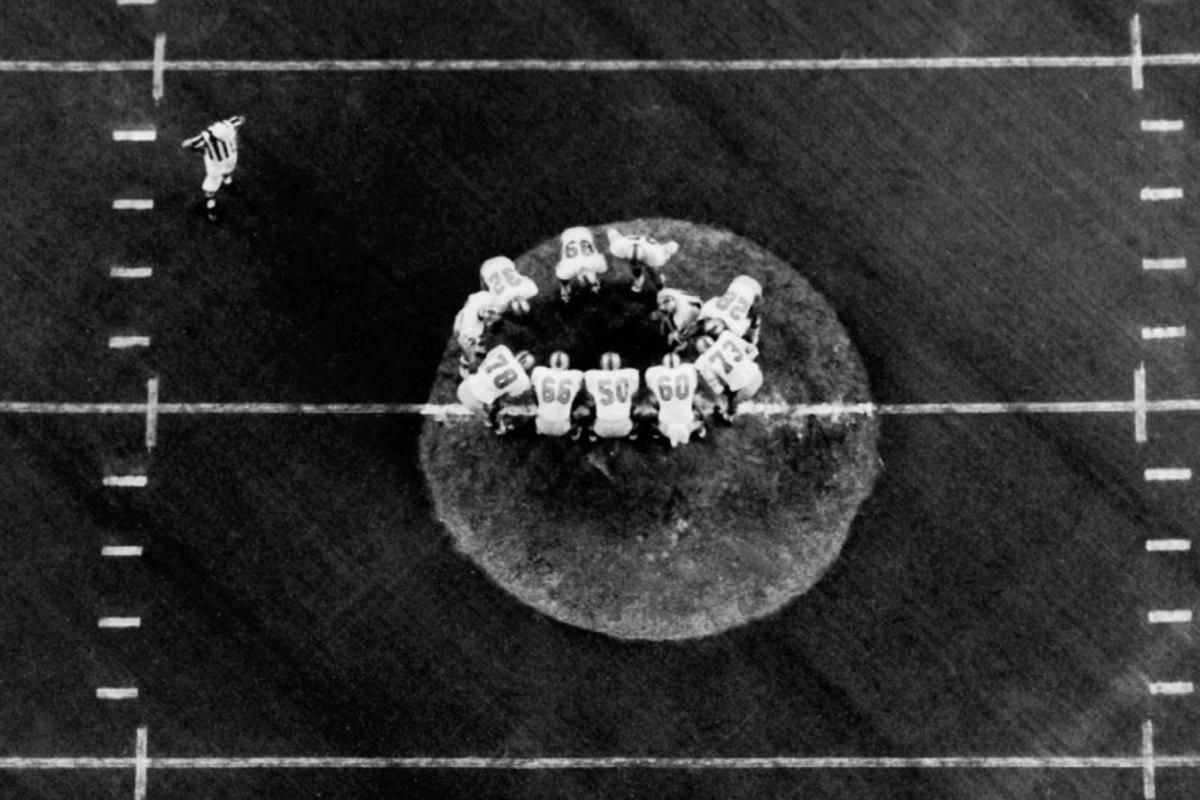

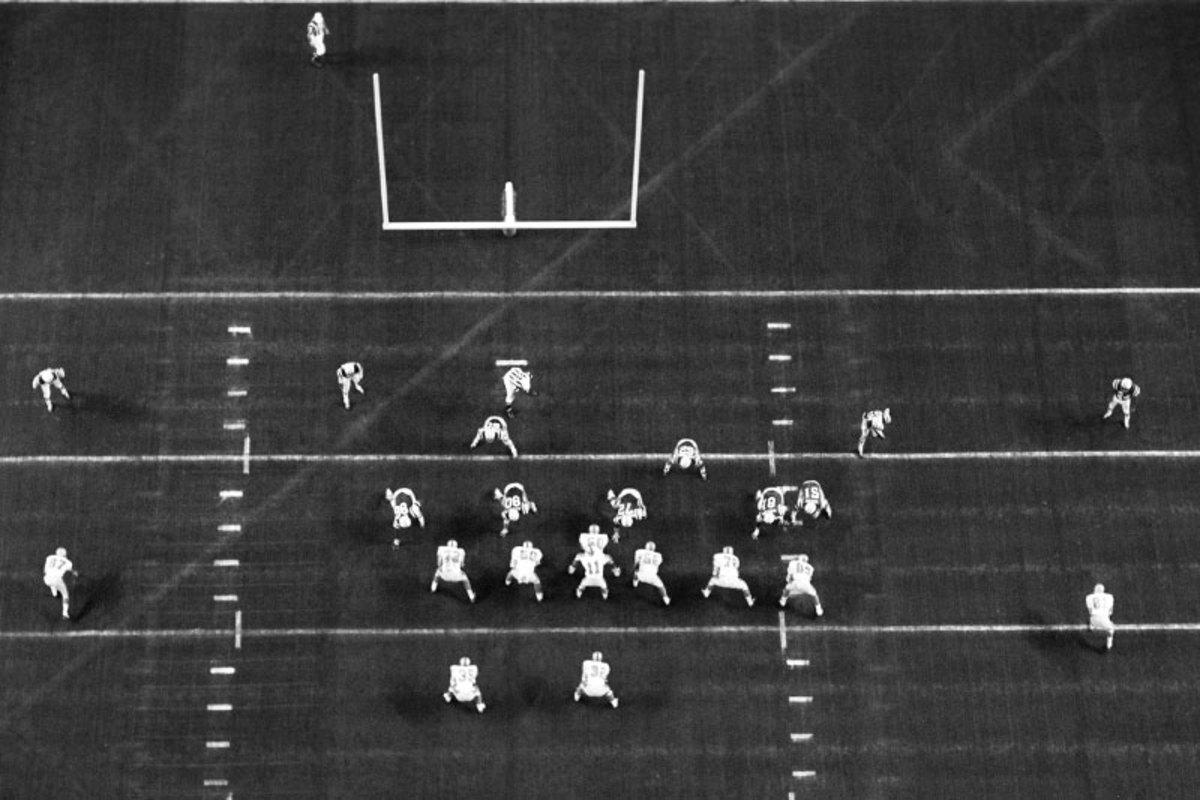

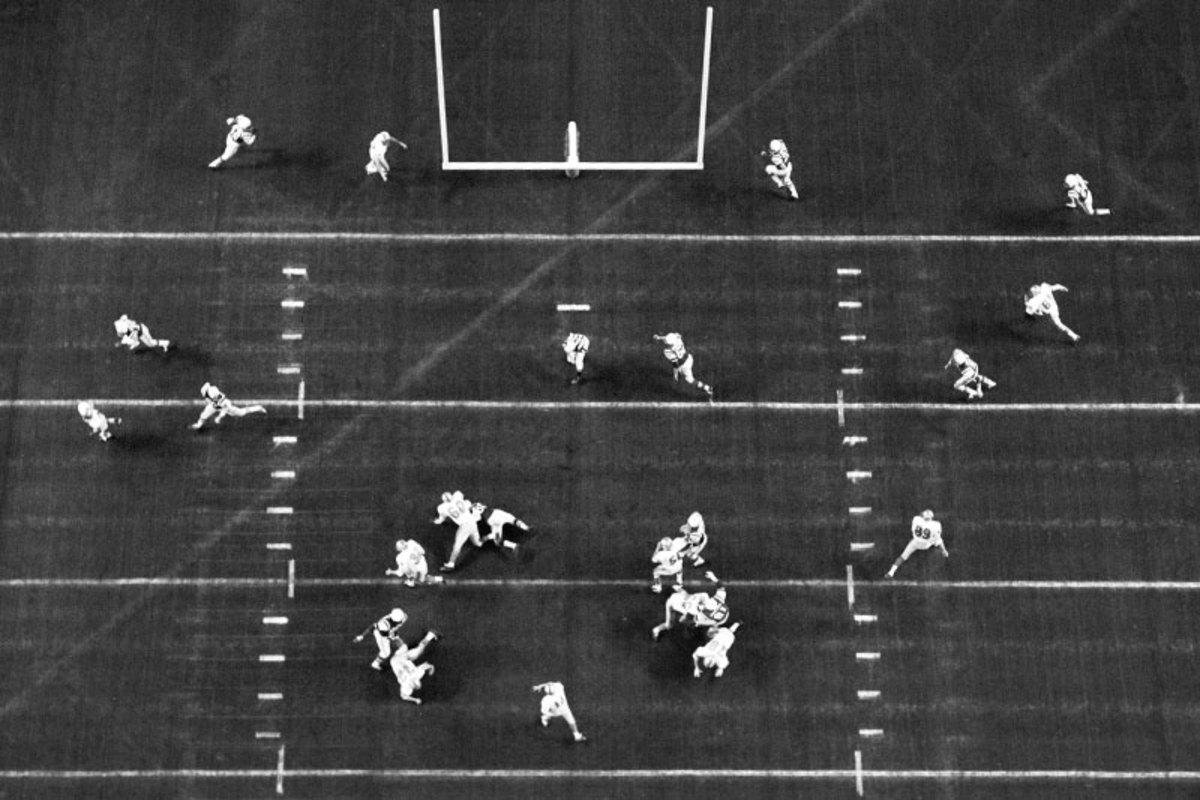

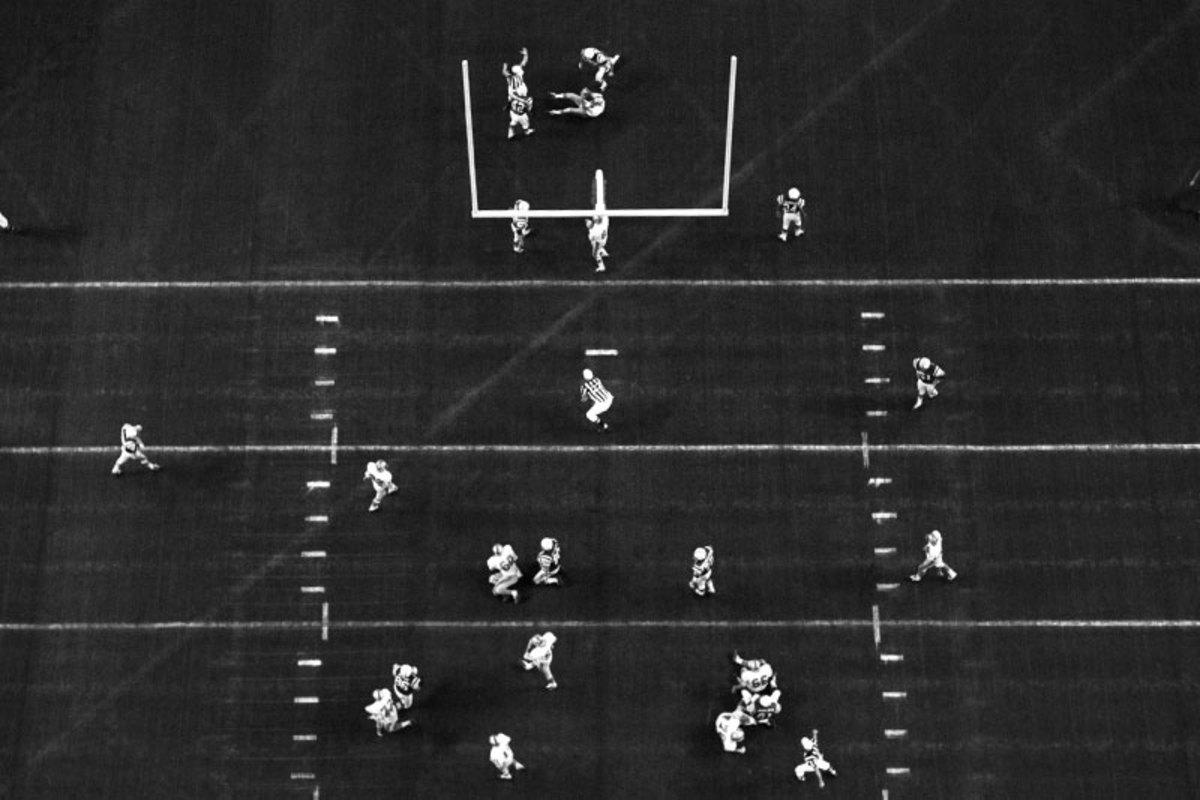

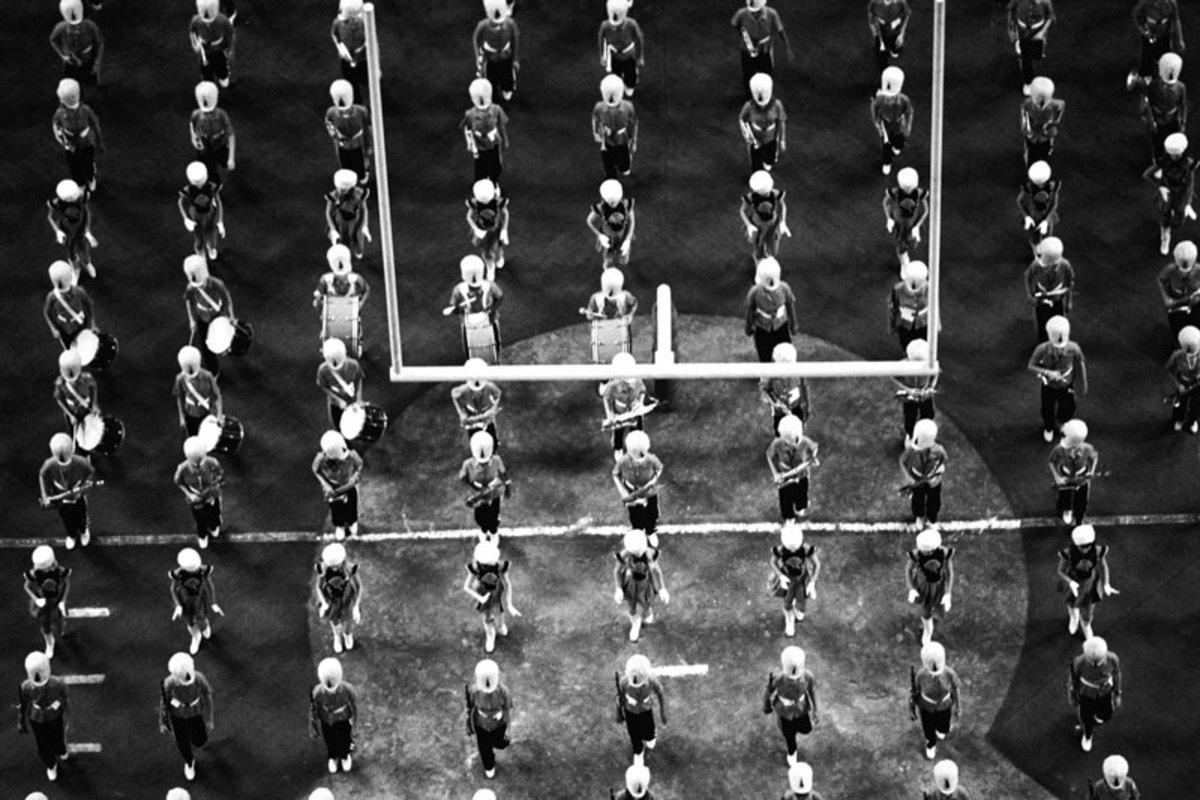

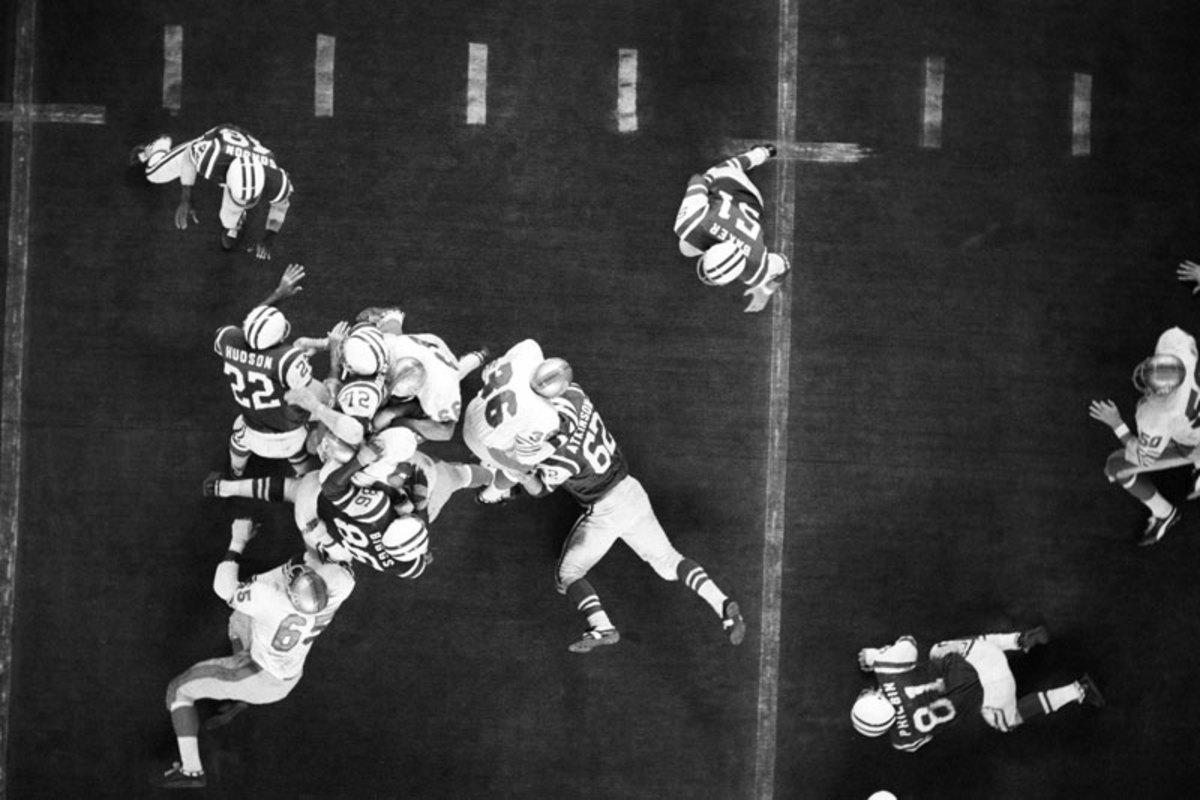

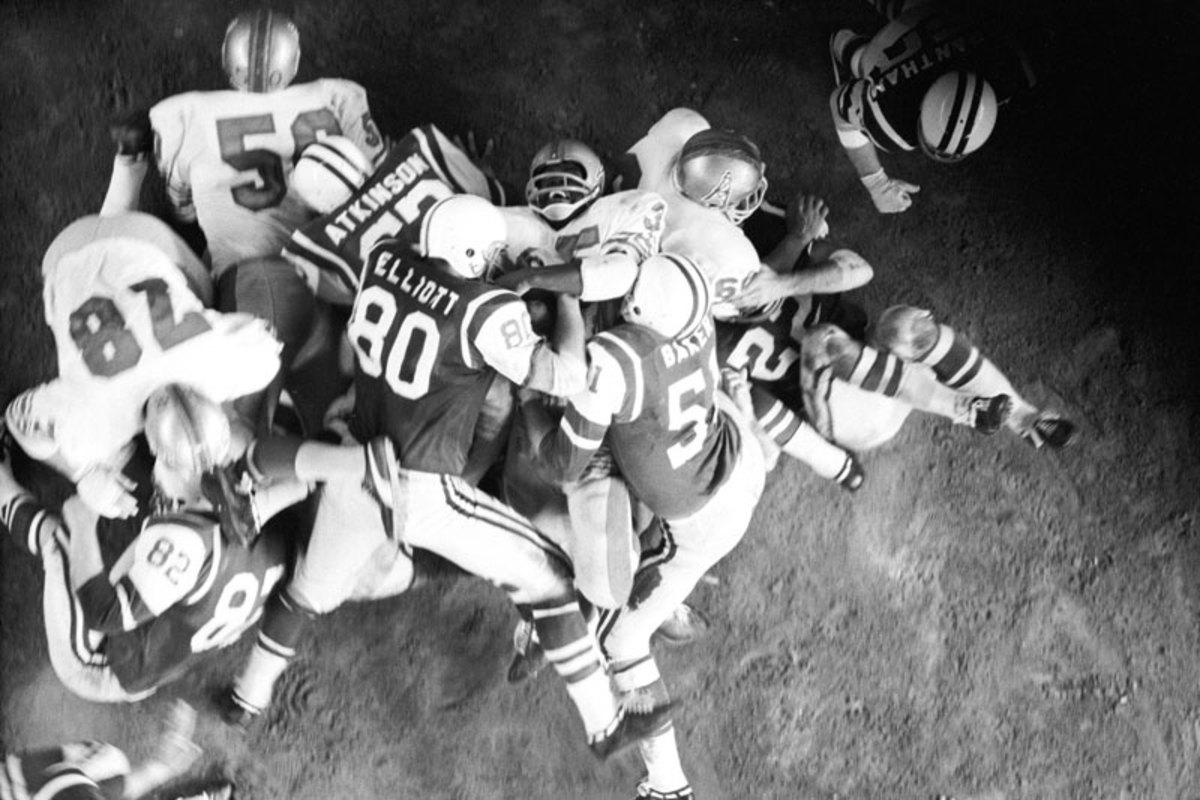

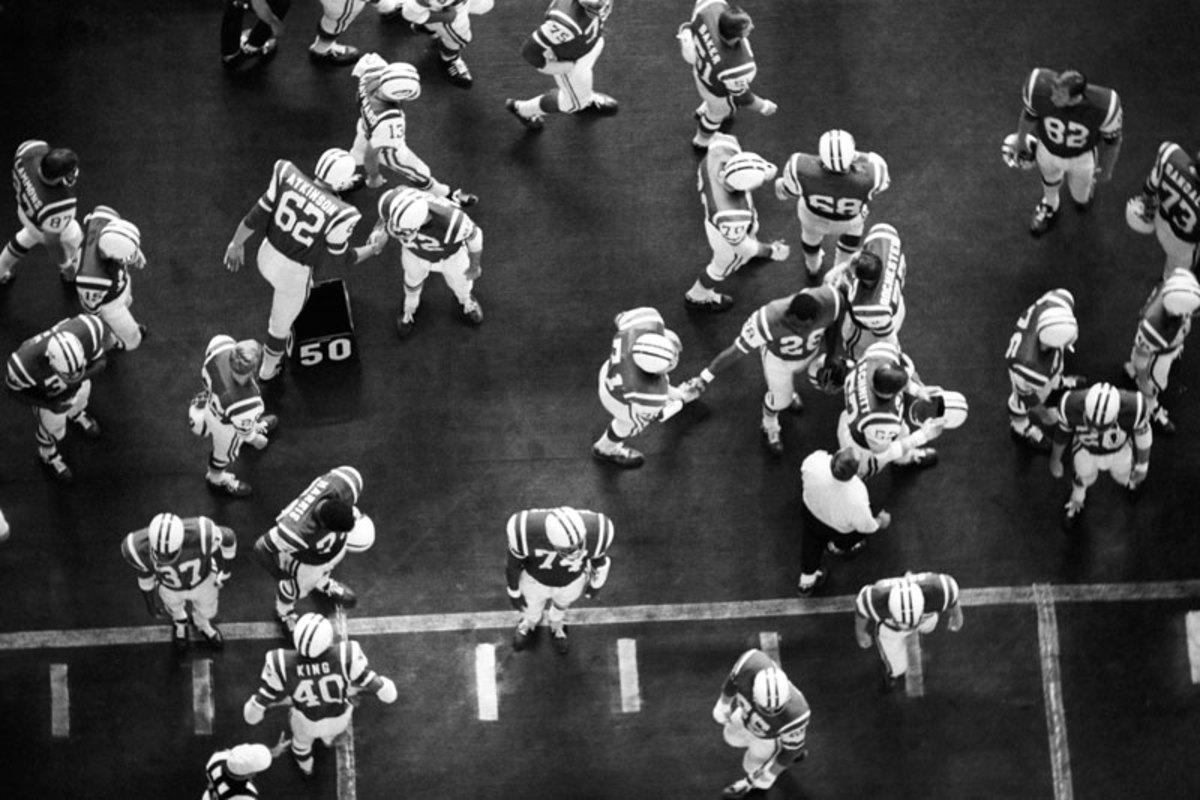

On Oct. 20, 1968, Sports Illustrated photographer Neil Leifer set up his camera high above the astroturf in Houston, when the Jets played the Oilers at the Astrodome in just the fourth pro game played on the new synthetic surface.

turf-astrodome-overhead-17-nl.jpg

turf-astrodome-overhead-31.jpg

turf-astrodome-overhead-6-nl.jpg

turf-astrodome-overhead-11.jpg

turf-astrodome-overhead-21.jpg

turf-overhead-astrodome-9-nl.jpg

turf-overhead-astrodome-8-nl.jpg

turf-astrodome-overhead-13-nl.jpg

turf-overhead-astrodome-12-nl.jpg

turf-overhead-astrodome-11-nl.jpg

turf-overhead-astrodome-10-nl.jpg

turf-astrodome-overhead-14-nl.jpg

turf-astrodome-overhead-16-nl.jpg

turf-astrodome-overhead-7-nl.jpg

There were practical reasons for the embrace of plastic grass. In 1976, there were seven so-called multi-use stadiums in the NFL, facilities like Three Rivers, Riverfront (Cincinnati) and Candlestick Park (San Francisco) that shared time with baseball teams. (There is just one dual-use venue now, in Oakland; it has grass.) Artificial turf was a godsend for groundskeepers who couldn’t sustain or grow suitable natural grass. “Now we can sod a field and play on it the next day,” says McNitt. “That was not the case in the 1970s.” Still, most of the early synthetic fields were made up of green carpet glued to asphalt. They were undeniably hard, and none worse than The Vet in Philadelphia, with its wasteland of seams and bubbles, lying in wait to snag unsuspecting visiting players.

“There was one spot, I think it was where the pitcher’s mound was,” says former NFL defensive back Eric Allen, who played for the Eagles from 1988 to ’94. “It was hollow underneath. You would run across there and it would be, like thump, thump, thump. Guys were wary of coming there and playing against us, because the field had such a bad reputation. I would walk around during warmups and talk to the [opposing] wide receivers—‘You better watch out, there are some rough spots out there’—you know, just trying to get them to slow down and think about it.”

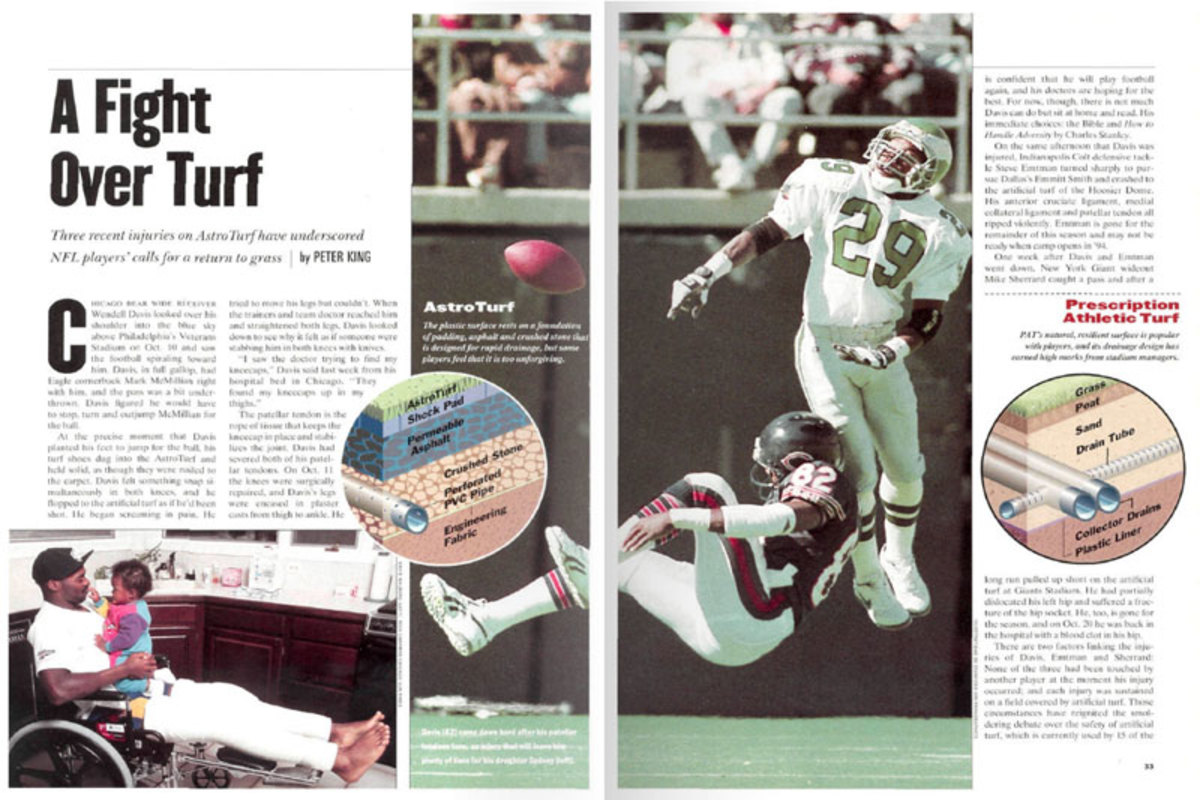

On Oct. 10, 1993, Wendell Davis of the Chicago Bears wasn’t thinking about it at all. He was a sixth-year wide receiver who had been drafted in the first round in 1988 after catching passes for more than 2,700 yards and 19 touchdowns in three seasons at LSU. Davis worked his way into the Bears’ starting lineup in 1989 and two years later led an 11-5 playoff team team with 61 catches for 945 yards and six touchdowns. He followed that up with 54 catches in ’92 and came to the Vet in ’93 with 12 catches in the first four games of that season. It was the 71st game of his professional career and his first trip to Philadelphia. He liked playing on grass, such as at in the lush stadiums of the SEC (where even Alabama and Florida each had artificial turf for a time), but he didn’t hate artificial turf, either. “I felt like it made you quick,” says Davis. “Made you feel faster.”

He had caught three passes that day for 38 yards when he lined up across from Eagles corner Mark McMillian in the third quarter and then burst off the line. “Simple back-side post route,” says Davis. Bears quarterback Jim Harbaugh threw to Davis, but the pass was high and behind the receiver. “I planted my feet, turned my body and jumped,” recalls Davis. “Then I heard two pops and landed flat on my butt. I looked down, and my kneecaps were up in my thighs. I thought, You’ve got to be kidding me.”

Davis, then 27, had ruptured both patella tendons leaping off the Vet’s carpet. It stands as one of the most horrific injuries in NFL history. He is 48 years old now, and recently moved from California back to Chicago; his son is a college football player. He is not by nature a bitter man, or given to accusatory rhetoric. “The way I moved that day,” says Davis, “I think my injury could have happened on grass. But I will say that was a very hard surface. No cushion at all.”

GALLERY: The Worst Playing Surface Ever

Artificial Turf: Change From the Ground Up

Wendell Davis’s freak injury on the notorious rug at Veterans Stadium in ’93 may have been a tipping point on attitudes toward artificial turf, and prompted an SI feature on its dangers.

Davis tore both patellar tendons when he planted to leap for a Jim Harbaugh pass; shortly after surgery, he was wheelchair-bound, with both legs in casts. (David Walberg/Sports Illustrated)

Two scars attest to the damage done; Davis never played another NFL game. (David Walberg/Sports Illustrated)

Crews worked the turf at the Vet in ’98, one of the dual-purpose stadiums built in the frenzy for functionality that began in the ’60s. (Chris Gardner/AP)

The city of Philadelphia, owner of the Vet, finally tore up the old astroturf in March 2001. (Jon Adams/AP)

The new surface had problems of its own: A preseason game against the Ravens in ’01 was cancelled when Baltimore coach Brian Billick complained that the field was too dangerous. (Tom Mihalek/AFP/Getty Images)

Donovan McNabb and the Eagles closed out the Vet's history with a playoff loss to the Bucs in January 2003. (Bill Frakes/Sports Illustrated)

Fans bid goodbye, though few players were shedding any tears for the Vet. (Bob Rosato/Sports Illustrated)

Long before Wendell Davis went down there had been blowback from players over artificial turf. As early as 1973 the NFL Players Association had asked for a moratorium on the installation of artificial turf. Yet injury data was—and remains—scarce. The most exhaustive study was conducted from 1980 to ’89 by John Powell, a researcher and athletic trainer at the University of Iowa. "Overall, there is a tendency for AstroTurf to be associated with an increased risk for knee sprains and MCL [medial collateral ligament] and ACL [anterior cruciate ligament] injuries under very specific conditions,” Powell wrote in the American Journal of Sports Medicine. But he also wrote, "It may be that participation on AstroTurf is the most important of all risk factors or it may be well down the list of importance."

* * *

Yet Davis’s injury has come to be regarded as the tipping point for old-school artificial turf. It was almost unique in its damage—Davis never played another down—and it took place on what was acknowledged as the worst surface in the league. Still, change occurs slowly in the NFL, and it wouldn’t be until 2004, 11 years after the Davis injury, that the league was entirely cleansed of first-generation artificial turf. The last gasp came in the 1999 season, when the St. Louis Rams, called “The Greatest Show on Turf” for their offensive explosiveness under coordinator Mike Martz and quarterback Kurt Warner, won the Super Bowl. That team went 8-0 on the indoor rug at what was then known at the TWA Dome, and, says Martz, benefited from the speedy surface in executing an aggressive downfield passing game that often required Warner to hold the ball much longer than in most systems. “We would all love to see games only on grass,” says Martz. “But on that old surface, guys could come out of cuts and change direction exceptionally fast. It was definitely a factor.”

Even then, movement away from the original design of artificial turf was well underway. By the middle 1990s, a form of artificial turf that utilized longer plastic fibers held upright and cushioned by crumb rubber infill was in production. According to NcNitt, Serensits and Sorochan, the first such field was installed at a Pennsylvania high school in 1997, and two years later at the University of Nebraska’s Memorial Stadium. (Visitors to that field would inevitably dig into the fibers and roll the little pieces of rubber between their fingers, soaking up the newness of it all while fighting the urge to get downright giddy). The surface was viscerally softer. Currently 13 of 31 NFL stadiums are fitted with artificial turf, and all are some variety of infilled surface. (Denver’s Sports Authority Field at Mile High Stadium is a natural grass surface with synthetic fibers sewn into the turf).

FieldTurf and similar next-gen surfaces employ rubber pellets, sand and other materials to soften the field and make its response more grass-like. (Pascale Simard/Bloomberg News)

Still, players overwhelmingly prefer natural grass. In the last survey performed by the NFLPA, in 2010, 69.4 percent of NFL players said they preferred natural grass to any form of synthetic surface. In a survey released by the NFL in 2012 and measuring games played from 2000 to ’09, knee and ankle sprains were shown to be 22 percent more common on FieldTurf than on grass and ACL sprains 67 percent more common. (McNitt, however, points out that lower-extremity injuries are not so simply assigned to the playing surface. “It’s the surface and the shoe,” says McNitt. “Footwear companies are making much, much more aggressive shoes.” On occasion the shoe will stick, and the knee or ankle or hip will move, often with catastrophic results).

The southernmost outdoor NFL stadium with artificial turf is Baltimore’s M&T Bank Stadium, which opened in 1998 with natural grass but in 2003 converted to infilled synthetic turf because the grass field deteriorated badly late in the autumn. This occurred not because of cold weather, but because the field received too little sunshine. “Modern stadiums are being built higher, to get fans closer to the field,” says McNitt. “That’s created a problem in getting sun to the playing surface for any significant length of time during the day.”

Brian Billick, who was the Ravens’ coach at the time of the conversion, says, “All our players would have preferred grass, but not the grass that we had at the end of the season.”

* * *

So plastic grass remains an active chapter, if an evolving one. Last fall Wendell Davis took his son on a recruiting visit and walked across a modern artificial turf surface. “So different,” he said. “So much softer.” He felt as if he was walking on a pillow. The old stuff is a part of his life. “A part of who I am,” he said. “Always will be.” A part of the NFL, too. A thin slice of hard, green carpet spread across the history books, and a lesson learned.

What’s been lost? More scenes like this one, when the 49ers and the Browns had a field day in the mud at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium in 1974. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

Week 2 Artifacts

Tom Dempsey's Boot The unlikeliest record-holder in NFL history, the man born with half a right foot kicked a 63-yard field goal for the Saints in 1970, a mark that stood for 43 years and prompted a new rule on footwear. read more → |

|---|

O.J. Simpson’s Ford Bronco The infamous SUV was at the center of a murder story that captivated the nation and turned a Hall of Fame running back and Hollywood superstar into the most notorious former athlete in the world. read more → |

Jerry Rice’s Hands Massive and supple, formed through grueling work as a bricklayer in his teenage years, they snared more passes for more yards and more touchdowns than those of any other player in history. read more → |

The Bednarik-Gifford Photo There’s no doubt that brutality fueled football’s popularity—just consider SI photographer John Zimmerman’s picture from 1960 of Chuck Bednarik-Frank Gifford hit, which became one of the iconic images in the game’s history. read more → |

Ryan Leaf’s Colts Jersey How might things have turned out had Indianapolis taken Leaf rather than Peyton Manning first overall in 1998? A blue shirt hanging on the set of the Dan Patrick Show offers a frightening glimpse of an alternate NFL history. read more → |

Notre Dame vs. Giants 1930 Game Program A forerunner of the NFL’s many charity endeavors, this game between the Giants and a team of Notre Dame All-Stars raised more than $150,000 for the unemployed at the height of the Depression. read more → |

Arthur Blank’s Napkin It’s a cliché that great ideas and momentous business deals are drawn up on napkins over dinner. But that’s exactly how the Home Depot magnate bought the Falcons and changed the course of the franchise. read more → |

The 1933 Rule Book Early on, rules governing the forward pass were so onerous that the tactic was rarely attempted. A little tweak in ’33—allowing a pass from anywhere behind the line of scrimmage—opened the way to the game we now know. read more → |