Bill Walsh’s Coaching Tapes: An Enduring Genius

Editor’s note: This is the third in The MMQB’s 10-part series NFL 95: A History of Pro Football in 95 Objects, commemorating the 95th season of the NFL in 2014. Each Wednesday through the start of training camp in July, The MMQB will unveil one long-form piece on an artifact of particular significance to the history of the NFL, accompanied by other objects that trace the rise of professional football in America, from the NFL’s founding in a Hupmobile dealership in Canton in 1920 to its place today at the forefront of American sports and popular culture.

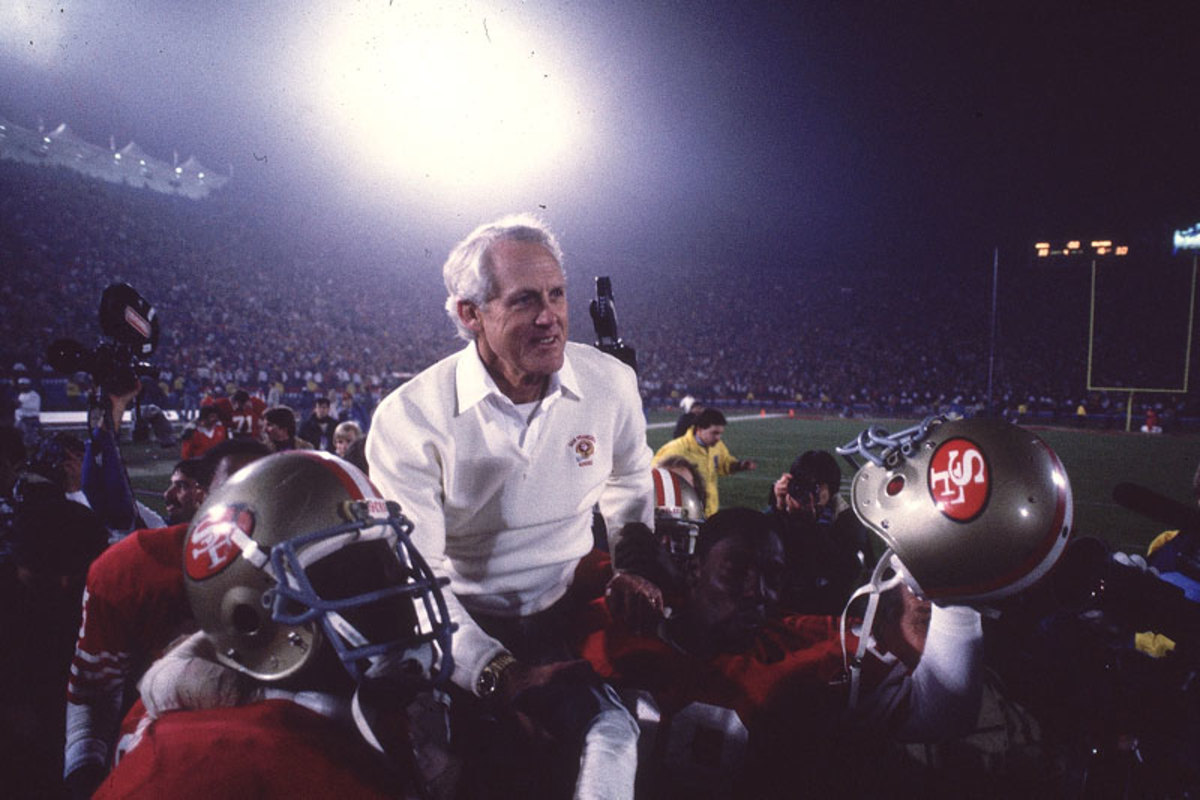

SANTA CLARA, Calif.—There he stands, exactly how you picture him in your mind. Tanned, fit, flowing white hair. His dress switches from the normal Sunday attire—white sweater over a collared golf shirt, neatly pressed slacks—to trim T-shirt tucked into red coaching shorts. The tone of his voice, measured, passionate and, above all else, professorial, is as comforting as a well-worn pair of slippers.

Your initial impression is that you’re watching a ghost, considering he’s been gone nearly seven years now. But his presence is so strong, in the building, in the coaching staffs around the NFL, in the offensive and team management concepts still being employed, and, especially, on the screen in front of you, that you’re certain the vision of former 49ers coach Bill Walsh is no apparition.

Walsh most certainly lives on, and will for many years. The excellence sustained by his 49ers teams—92-59-1 in the regular season, a .714 postseason winning percentage, three Super Bowl titles in six years and a fourth by protégé George Seifert the season after Walsh retired—is reason enough. But so are the videotapes he left behind.

NFL 95

The MMQB presents NFL 95, a special project—unveiled every Wednesday from May through July—detailing 95 artifacts that tell the story of the NFL, as the league prepares to enter its 95th season. See entire series here.

Walsh filmed nearly all of his meetings and practices during his tenure with the Niners, from 1979 to ’88. Many are in the possession of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, which sent back copies to the franchise soon after Jim Harbaugh was named coach and requested they be returned in 2011. Several are missing, believed to have landed in the secret stashes of assistants connected to Walsh and the 49ers over the years. The list of coaches who worked directly under Walsh or occupy a prominent perch on his coaching tree is long and distinguished: Seifert, Paul Hackett, Marty Mornhinweg, Andy Reid, Bill Callahan, Sam Wyche, Steve Mariucci, Mike Holmgren, Mike Shanahan, Mike McCarthy, and the names continue. Shanahan, the story goes, learned the West Coast offense just from watching the Walsh tapes. Harbaugh’s staff spent the 2011 lockout studying the films.

Now you’re sitting in front of them in the Bill Walsh Room at the 49ers’ training facility. On the wall hangs a picture of Walsh, lying on an equipment bag on the locker room floor before a game, hands behind his head, legs crossed. He’s the image of calm before the raging storm that is professional football. Yes, Walsh lives on.

Precision

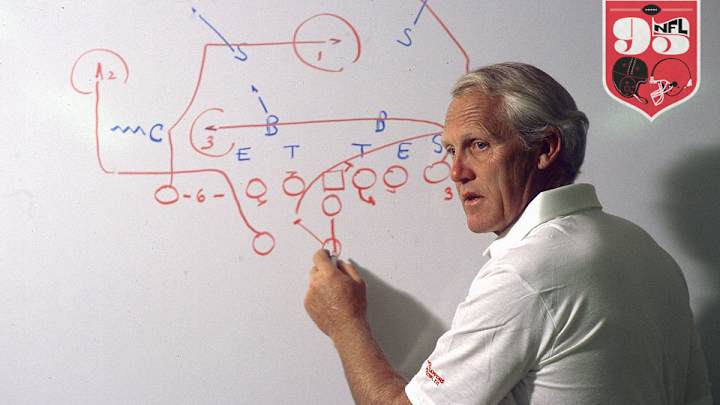

“It’s that simple.” (Michael Zagaris/Sports Illustrated)

Several factors regarding Walsh’s strategy, coaching style and overall philosolphy stand out after you watch hours of the Walsh tapes. The first factor is precision. Every movement on the field was choreographed by Walsh, to the point where he detailed even the placement and positioning of the blockers’ heads on individual plays.

The following is just part of Walsh’s explanation of a run play called “18 Power,” recorded during a meeting before the 1984 season opener against the Lions. Keep in mind, the play has already been installed. This is review.

What we want here is a 1/2 to 2-yard split right here with the flanker. With our flanker blocking down, his head on the upfield side, with our tight end blocking straight out, right down the middle [of the opponent], make sure your head is slightly on the inside. Go straight out and hit this guy with your hat just on the inside, knock him straight back. The two of you take this guy for a ride. Once you feel like you've got him turned, then our flanker can slip off and pick off the [middle] backer, just like we've drawn it.

Now the critical part on 18 Power is the tackle’s block. He's blocking by himself, and the ball has to get all the way over here. So it's your job not to try and turn the guy, try to knock him straight back, your hat slightly on the outside. You have to account for him going down inside on you, and if we can find a way to read it a little better, we’ll do it. But that's the critical block that we have to sustain. We can't try to do anything with it because he can come around [the block] very easily. So sustaining the block is critical, not doing anything else. The guy can't go anywhere. If he goes outside, you sustain the block and he goes right into the double team. Now our guard will naturally double and then rub on the W [weakside] backer. Get a good part of this guy and then be ready to pick him off.

Got that? There’s more, just in the blocking instructions:

We seal back side, our guard is going to pull, but as you pull just run a full-speed course around the flanker's block and then look back up. Remember, [look] 70 percent inside, 30 percent outside. But, again, if this M [middle backer] is scraping through here, you want to try to cut him down rather than stand up and block him. Because what happens is if you stand up and hit him, you're sort of bounced back right into the hole. So you want to run full speed, alert for the M as you come by. That's the critical part of it. Our fullback goes inside out and runs a power block now on a strong safety. Your course is just inside through the strong safety. I'd say you go for about two feet outside the TE position, splitting the difference. If he comes inside of you, it will all get pinned. If he's outside of you, you kick him straight out. If he crosses the line you turn him out. But you keep that power block like you do on any speed backer. Block him, knock him straight back or turn him out.

But the difference now, here fullback, is you cannot just unload because this guy is much quicker on his feet than one of these guys would be. He can actually make you miss by just dodging. So you really have to keep your feet up underneath you. Get him more standing up or flush down the middle. Because if you don't stand up and block him, he'll dodge you. He's a good enough athlete out there. You have to be careful. It's always possible, halfback, as we double team and sort of move a little bit, our pulling guard fills in and then you guys both turn up inside the double team. But most likely, it’s just like we have it drawn. Stretch it and break it.”

Sounds complicated, but there is a simplicity in the way Walsh explains plays on these tapes. There is little doubt that the best football coaches share the gift of making the complicated simple for the players. Walsh has that ability to make every player feel comfortable with his assignment so that it fits together perfectly with the whole. And he often punctuates each explanation with a three-word phrase to drive home the point: “It’s that simple.”

Walsh and his offensive line coach, the late Bob McKittrick, constantly harped on a players’ “course,” the direction and speed of his running or blocking on any given play. They wanted every player’s movement to match up precisely with the other 10 men on the field and with the play. Some plays called for a slow course. Others fast. Timing in football, Walsh latered explained, was critical.

He put more value on knowing where you had to be,” says Guy McIntyre. “He teaches perfection without saying it.

The need for precision extended beyond the players’ assignments on the field. It was an essential part of the coaches’ play-calling as well. Walsh thought so far ahead that he’d tell quarterback Joe Montana a certain play would only be run on second down, because there was a reasonable chance Montana would have to throw the ball away. Walsh didn’t want that to happen on third down.

“He put more value on your knowing where you had to be, because I don't care what kind of talent you are, you're going to mess up everybody else if you’re not in the exact right spot,” three-time All Pro guard Guy McIntyre, a rookie in ’84, said while reviewing some Walsh tapes. “His point was to make sure that everybody, not just himself but every coach, had the ability to teach to the finest little details that would make a difference in a game. You can hear how he talks about throwing the ball. It's got to be here, not there, not too early, not too late, it has to be in this window. It has to be precise. That’s taught now, but it wasn’t back then. He teaches perfection without saying it.”

Confidence

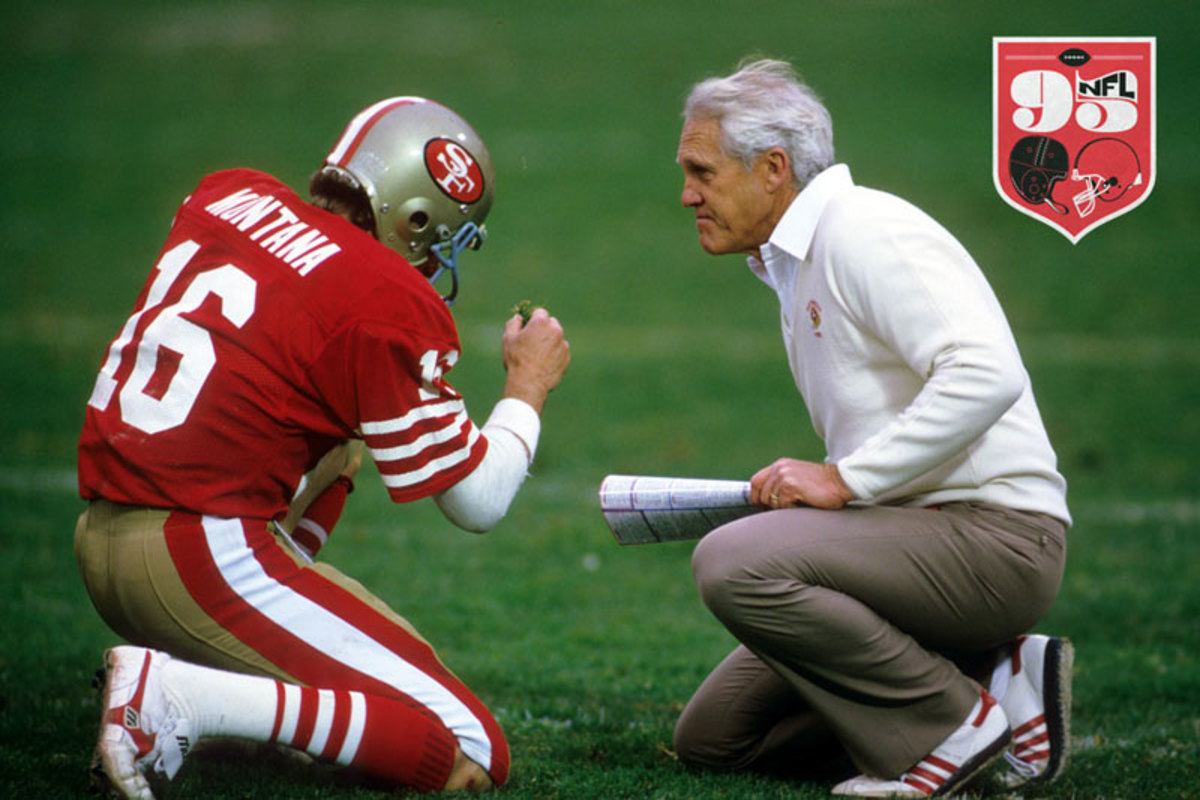

Walsh with Joe Montana in the NFC Championship Game against the Bears, January 1988. (Richard Mackson/Sports Illustrated)

The Bill Walsh on these tapes speaks with extreme assurance, especially on the final Friday meeting before a game. There is never any doubt in his voice.

"The linebacker will be here so you should look for the ball here."

“This play looks especially good to us.”

“98 Boss, hell of a play.”

“This looks good too because now they have a corner that's supporting. Very very well done. Should be a good play for us.”

“If they're in Cover 9, this short-yardage pass Halfback 2 Flanker Snake might go 95 yards. We go ahead in ‘U’ formation, we're backed up and they're in [Cover] 9, we're going to beat them. We've got it right down the middle for the touchdown.”

Other coaches might feel that ruling by fear is the best course of action. Walsh obviously felt that a confident ball club was the best club.

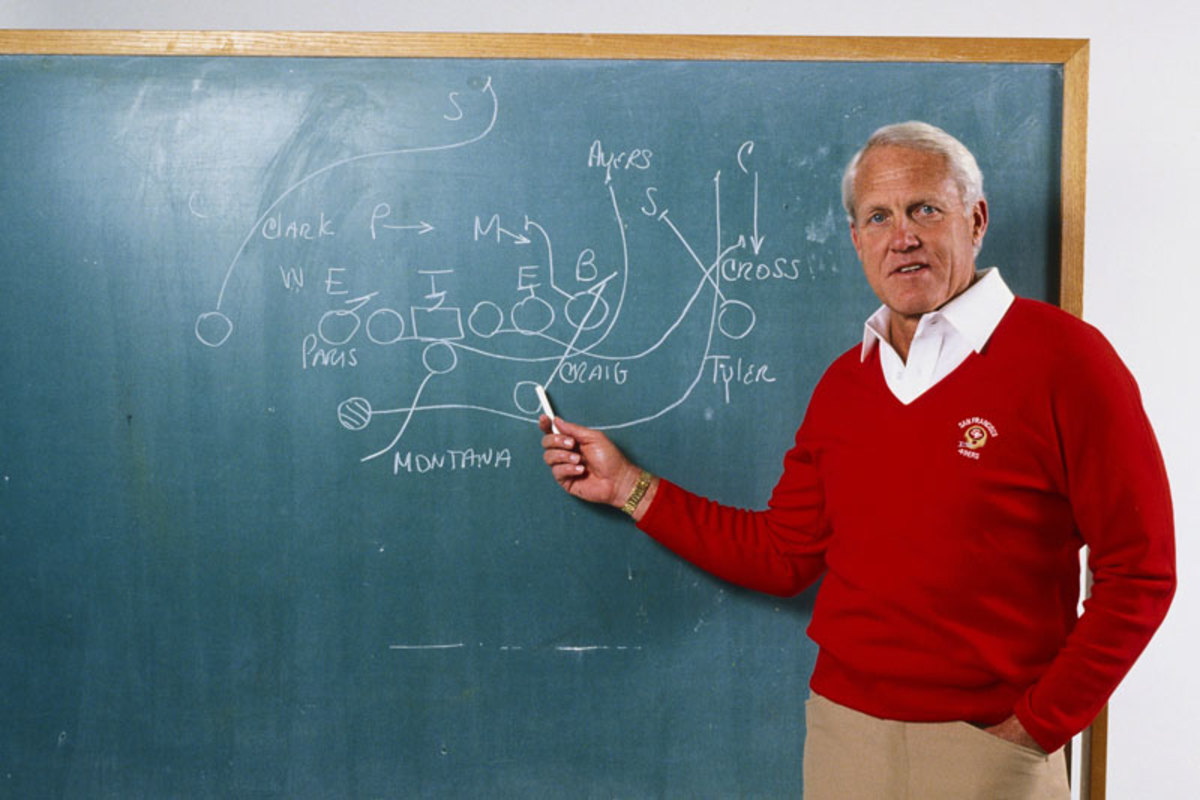

Intimacy

The recordings show Walsh’s easy manner in the locker room and a clear concern for his players’ well-being on and off the field. (Michael Zagaris/Sports Illustrated)

The Walsh tapes don’t address just X’s and O’s. He may have played the part of a professor, but it was his ability to relate to the players that had them behind him at all times. He often included himself in his discussions, to project an “us against them” unity as well. Here he is offering instruction to players on dealing with the media.

Every year you're going to have a calculated approach taken by a couple writers, especially when you're doing well, to take the team apart. And they delight in it. They like to see you squirm, they like to see all of us squirm. If they could feel they affected us and we didn't do well, they have won the war. It's that simple. I guess we're fortunate we don’t have more of them. If were in New York City or some place it would be eight or 10 of them doing this. But every year, the same guy locally, there's a couple of them, will do anything they can to disrupt us. They can make it black and white, defense versus offense, coaches versus players, owners versus coach. They'll do it every conceivable way, and they'll get a formula and a plan and methodically work on it. And they work on it. They really calculate it. These guys are not simple-minded people. They’re very bright guys. Just find a way to deal with this stuff, because it will happen. We'll have two or three things come up, we don't even know what they are yet, but he'll come up with something to try to break us. And nobody's going to break us. Nobody's going to take us apart.”

While the physical well-being of players has become a prime concern in recent years, it already was for Walsh and his 49ers three decades ago. Eight former players recently filed a lawsuit against the league, alleging that team medical staffers did whatever they could to keep players out on the field, with little concern for the health implications. Compare those assertions with this talk Walsh had with his players, and it’s hard not see why he was so loved by most of his former players.

One of our primary responsibilities is your safety on the field, and then your treatment off the field. If anybody suspects that part of it, you certainly should approach me personally because our main responsibility in coaching a game like this is your personal safety. I just want to remind you of that. I think we have the best team physician in football, best orthopedic man and best practice because he has a staff that works with him. One of the best trainers. It's true from our owners and the rest of the organization—your safety and your well-being is most important. We've made one or two mistakes putting people back in the game that were injured, happened once last year, but it rarely gets by. It rarely does. I couldn’t live it with it if in any way I took a chance with any of your well-being.

Walsh also expressed concern for his players’ financial well-being, giving several lectures on how they could make their money last.

If there are five guys in this room that made money on investments, I want to see them after and get their names and get involved myself. I've made the same mistakes. I've lost. [Team president] John McVay and I are in a deal right now—we can sell you some land across town. You name it, it's yours. Just start making the payments on it. We were going to develop it into a shopping center, only problem is no one lives over there.

Sprinkling humor was important to Walsh. When he organized a team fishing tournament, he made fun of the “city fellas” who had probably never seen a fishing pole before. Walsh jokingly tried to get some players to work out after a game and asked who was going to wear their Speedos. Before a playoff game against the Bears, one 49er made a wisecrack in the back of the room, and Walsh asked if that was Jim McMahon. The humor never feels forced or falls flat. For all his reputation as an intellectual and an introvert, Walsh obviously walked easily among different groups.

Big Moments

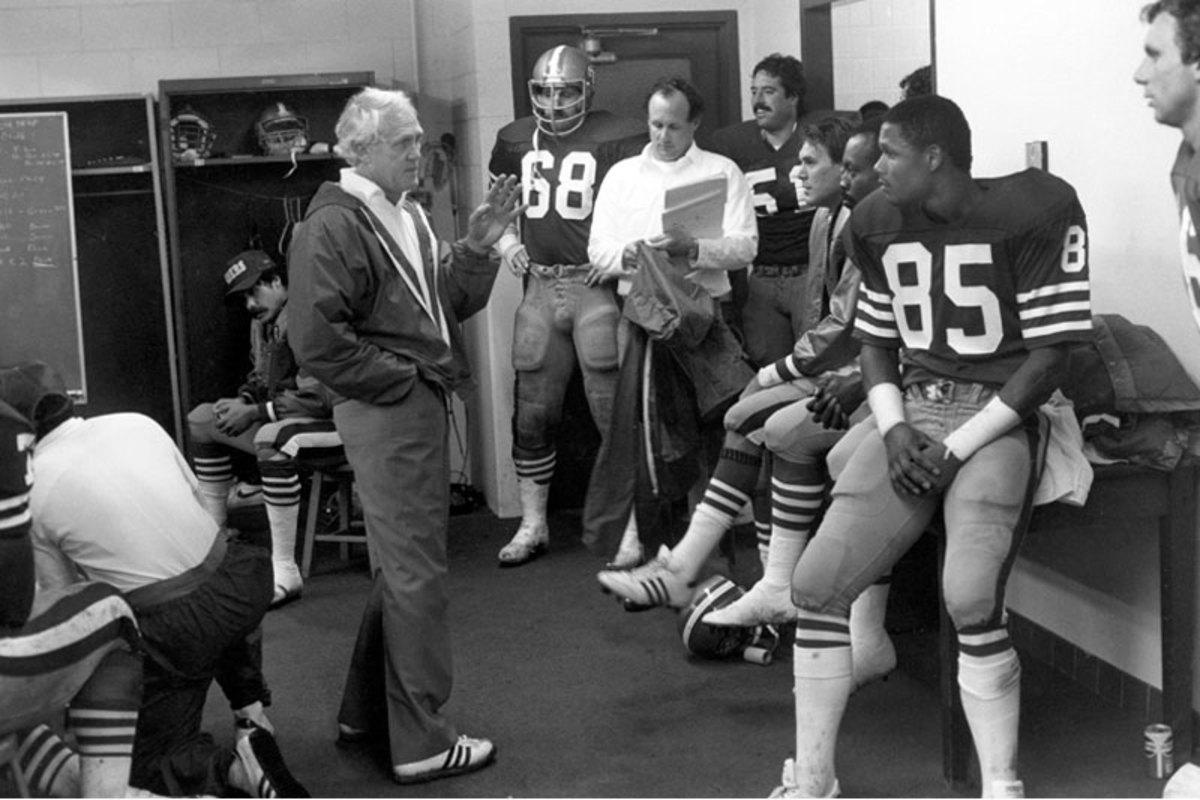

Walsh and then-assistant Sam Wyche (far rtleft), one of the many disciples who would go on to spread the gospel in the ensuing decades. The two would face off in Super Bowl XXIII. (Carl Iwasaki/Sports Illustrated)

A tape from the middle of the ’84 season shows Walsh at his best. The 5-0 49ers were set to collide on Monday night in the Meadowlands against the 3-2 Giants of Bill Parcells, Lawrence Taylor and Phil Simms. Walsh set the scene like a virtuoso conductor:

New York City has got that air about it. It's a crazy place, but it's really the mecca of the whole country. Whether you're an athletic team or an entertainer, actor, musician, whatever—performing in New York City, one of the best places, is the ultimate. Now we're going in there as an undefeated football team, and this is where your performance is looked at by everybody. As you guys know, the critics in the country generally start there. Everybody looks at you from there. And the pressure is on you when you go there and perform. The pressure's on. There's been a lot of hyped up athletes and musicians have gone there and failed and have been staggered out of town. A lot have gone there in the last 200 years and not made it, been embarrassed and were never asked back. We’ll be asked back, it’s on the schedule someday. The point is, we go in with a lot of pride and we go in with a lot of accomplishment, and they now test us in New York City. This is not Duluth or Albuquerque. This is the Big Apple. This is the mecca of the United States, or the world. There are critics, the fans there are the most active and most critical.

Now there's all kinds of way to go there as a football team. One of them is just to be a great performing team that goes into New York City and methodically destroys their finest. Go in there and destroy their finest and leave town. You'll know that you went to NYC and did it. It's that simple. That's the challenge. The other way to do it is to go in there flat, go in there distracted because the plane flies over you see these tall buildings, there’s a little action in town. You go in there and do that and you'll make a goddamn fool of yourself and fall on your face. It generally goes either way.

It's my job and the coaches’ job and the leaders of the team to make sure we go in there as champions and dismantle this New York Giant football team and leave town knowing that we did it in New York City. It's that simple. I've been through it. A lot of you have. But now we're going in there as, maybe, a great football team. Who knows? Maybe we're great. And they're going to recall what they saw of us. If we're going to be great, this the place to be great, New York City.

[si_video id="video_DE2BF61E-12AC-3AC4-C6DE-42BE863A28DB"]

In his game-planning, Walsh didn’t let on one bit that Taylor and the other great members of that defense—Leonard Marshall, Carl Banks, Jim Burt, Harry Carson, Super Bowl champions two years later—would be a formidable opponent.

If they blitz them, they're good, but hell we've blocked them before. You go inside out. We'll pick [Taylor] up with our guard.

This team's pass rush is fair to average. Not great. So if Taylor is blocked, we're in pretty decent shape with the other people.

Final score: 49ers 31, Giants 10. A tape from the following Tuesday:

We did a hell of a job the other night, did what we talked about doing at the start of the week. So that's one project completed. Can't say we didn't go back there and play a great game. The next one, of course, is the Steelers. They have a history of putting people out of the game. The Bengals game, they put eight guys out. These guys are a damn tough opponent.”

The 49ers fell to the Steelers at home, 20-17 in a game with several controversial calls. It would be a lesson learned for the Walsh and the 49ers. From a team meeting after the game:

We got beat to the punch, something we strive for. The other team was beating us to the punch. We took a beating. Our defense was not there by six inches on virtually every play. Our support, everything else. You look at the film, and you'll see most guys played that way. Can’t tell you exactly why. Offensively it was much the same way. We had critical plays that weren't executed. We have to remind ourselves that every play is a critical one and they were all involved, 49 guys.

So they have a great team, we haven't lost anything in the standpoint of our future and in this competitive league you have to give credit to the opponent. We'll give it to them. But the next time we take the field, men, I don't care which team it is, we have this taste in our mouth one too many times. I don't want to suffer through this any more than you do. I don't want that sick feeling of losing a game that you should have won or could have won. That sickening, lousy feeling. You know how it is. It's no fun. So the next time we go out there, the Houston Oilers are going to have to take the wrath of what we have to give out. Whether they like it or not, they're going to have to take it. And we have to go into that game feeling that way. That's the only way to get this out of your system, and that's to knock the hell out of somebody as soon as you can.

That Sunday at Houston the 49ers built a 20-7 lead and went on to win 34-21. San Francisco would not lose another game that season, going 18-1 and beating the Dolphins 38-16 in Super Bowl XIX.

Fast forward to July 1985, and the reigning Super Bowl champions were at the start of training camp. It was time to forget about what the 49ers had accomplished the previous, and to do it all over again. Walsh went back to where it all starts: the team.

What in the hell difference is there [among NFL teams]. There are some with the same athletic ability, unfortunately for us, but that's the case. We take pride in our great quarterbacks, there are great ones around the league. The critical difference has to be how we play as a unit, how we work together. That's the difference between us and everyone else. Some teams are much better at it, some will be at the bottom every year because they don't play well as a unit. They don't have the same respect, dignity related to each other. They don't have that. They don't communicate. They don't work well together. The chemistry is the critical part of it, and it doesn't show up initially in any given game. Every time you take the field the chemistry part of it shows late in the game. So you have to remind yourself, it's not our athletic ability that's going to knock the jocks off these guys. It's how we play as a team, how we're made up, the confidence we have in each other, and just how effectively we work as a defensive unit. That's the difference too. That's basically the difference in our ball club, and it was last season. We're just better put together than the goddamn L.A. Rams. It's that simple. I know they all want to win and beat us, but goddammit they can't do it because we play better as a unit than they do. It's just one of those things. And that's the part we have to keep.

The Legacy

Frank Gore’s Super Bowl XLVII touchdown was a classic Walsh play with modern pre-snap dressing. (John W. McDonough/Sports Illustrated)

February 2013. Super Bowl XLVII in New Orleans. With 5:05 remaining in the third quarter, Jim Harbaugh’s 49ers have first and goal at the Baltimore 6-yard line, trailing the Ravens 28-13. The dressing on the play—a shift from Colin Kaepernick under center and tight ends Vernon Davis and Delanie Walker on the right, to the shotgun and double tight ends left—is new-school, but the play designed by Walsh disciples Harbaugh and offensive coordinator Greg Roman is straight out of Walsh’s playbook: old-school counter play off of sprint-out action.

Kaepernick looks as if he’s going to sprint left for a pass, and running back Frank Gore sells it momentarily by faking a block. But left guard Mike Iupati is pulling along with Walker from the left to the right. Iupati turns Ravens outside linebacker Terrell Suggs to the inside, Walker cuts down safety Ed Reed, and receiver Randy Moss holds off cornerback Corey Graham to the inside just long enough for Gore to score untouched.

“It’s dressed up with a bell and whistle there, but that was old vintage 49ers stuff right there,” said Roman, who studied the Walsh tapes as an assistant under Seifert in Carolina, and with the 49ers.

“I think the ties are stronger than ever to what Walsh taught and believed in. Much of what we see now in college and pro football are extended handoffs, the high-percentage short and quick passing, because Bill passed the ball to set up the run most of the time, and the principles of how to attack space and isolate defenders, you see a lot of that. And that was Bill Walsh.”

So Walsh lives on. He does so through his accomplishments, through his book Finding the Winning Edge and, for those who have had a chance to watch these tapes from his 49ers days, through these recordings. Like grainy footage and audio of Vince Lombardi, they are perpetual gifts that link football past and the future. Through Walsh we can see the teachings of his mentors, such as Sid Gilman and, of course, Paul Brown. And through his many protégés—the long and branching line of his coaching tree—we can see Walsh. You don't have to those coaching these tapes to see his influence. It's evident in any game you watch today.

No, the Bill Walsh on these tapes is no ghost.

Week 3 Artifacts

Madden Video Game Legendary coach and broadcaster John Madden wasn’t the first or even the second choice to headline the EA Sports franchise nearly 30 years ago, but he’s become most famous for the annual game that now sells a million copies during its first week on the shelves. read more → |

|---|

Cowboys’ Cheerleaders Uniform The high-cut shorts and the bare midriffs drew criticism from feminists in the 1960s, but the sexy-yet-wholesome aesthetic has endured as a staple of NFL sidelines for generations. read more → |

Super Bowl Rings Vince Lombardi designed the first world championship ring, which featured a single round diamond and the words harmony, courage and valor. After winning Super Bowl XLVII, the Ravens had 243 round-cut diamonds on each piece of jewelry. read more → |

Tom Matte’s Wristband Without a healthy QB, Colts coach Don Shula called on tailback Tom Matte to step under center for three games in 1965. Running a simplified offense, his novelty wristband listing the plays quickly became commonplace at the position. read more → |

The Hupmobile In 1920, Canton Bulldogs owner Ralph Hay and the Decatur Staleys’ George Halas sat on the running boards of Hupmobiles, drinking buckets of beer while devising the American Professional Football Organization—renamed the NFL two years later. read more → |

Colts Marching Band Drum The Baltimore Colts Marching Band hasn’t stopped playing since being founded in 1947, even when it didn’t have a team after the ’84 move to Indianapolis. For the past 16 seasons, the ensemble has been called Baltimore’s Marching Ravens. read more → |

Chargers’ 1981 Playbook San Diego had a plan—and the perfect weapon—to block a field goal when it needed it most. Tight end Kellen Winslow got just enough of the ball, forcing overtime and allowing the Chargers to beat the Dolphins. read more → |

The White Football Long before night games were considered prime time, they were an oddity that required a white ball in case the floodlights faltered. The “egg soaring through the air” had two downsides: it was slippery, and blended too easily with white uniforms. read more → |