Rocky Bleier: The Chuck Noll I Remember

Editor’s note: When Chuck Noll was named coach of the Pittsburgh Steelers in January 1969, the team had had just seven winning seasons and one playoff appearance in its history. With his first draft pick that year, Noll took a defensive tackle named Joe Greene out of North Texas State, and the following year, after going 1-13, he drafted quarterback Terry Bradshaw. In the ensuing decade Noll would build and preside over one of the great dynasties in NFL history, a team that would win four Super Bowls in six seasons and send nine players to the Hall of Fame.

Noll, who played guard and linebacker under Paul Brown in Cleveland in the ’50s and served as an assistant coach under Sid Gilman and Don Shula, finished with a head coaching record of 209-156-1, including the postseason, in 23 years with the Steelers and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1993. He died on Friday night at the age of 82.

The MMQB asked Rocky Bleier, a fullback on those Steelers Super Bowl teams, to reflect on his coach.

By Rocky Bleier

It’s been several years since the last time I saw Chuck Noll. After much planning and prodding, he met with my former Steelers teammate Andy Russell and me for lunch in the Pittsburgh area one day. We considered it somewhat of a coup just getting to spend time with him. Chuck had a bad back and moved with a walker, and he had been relatively reclusive. When he later was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, his wife, Marianne, became very protective of Chuck and his interactions.

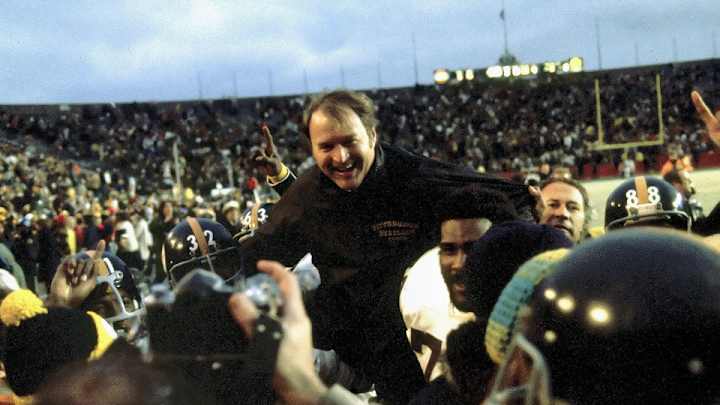

Chuck Noll on the sideline at Super Bowl X. (Rich Clarkson/Sports Illustrated)

Andy and I could tell there was something different about Chuck that day at lunch. You couldn’t quite put your finger on it, but he just wasn’t as sharp as we remembered him. Life has a way of taking the things we’re best at, if you’re lucky enough to grow old. The great runners lose their knees first. Detail was Chuck’s passion and expertise.

I remember in 1974, Chuck’s sixth season as coach of the Steelers and my fourth year back with the team after serving in Vietnam. We went out to Kansas City to play the Chiefs, and they had all the main players from their recent Super Bowl team, including Lenny Dawson at quarterback. We ran the ball well, we sacked Dawson two or three times, and we beat them. On Monday we’re going over the game film, and I was expecting Chuck to congratulate us on a great game. But not Chuck. Chuck said the reason we won this game was because of the lack of good habits formed by one person.

Chuck had a theory that we all eventually subscribed to: Habits are created every day in practice, and they carry over to the game—whether it’s 102 degrees on the field or 30, whether it’s raining or snowing, whether you have a 300-pound defensive tackle in front of you who’s pounding on you every day or no one at all. In the third and fourth quarter, you don’t think; you react.

So Chuck said, “The reason we won this game, gentlemen, is because of the lack of habits formed by Kansas City’s left guard. The reason why we had the sacks and the forced passes and why they had no running game was because of the habits formed by the left guard.”

I was dumbfounded. For a man to lead a team, the players have to accept and buy into what he’s teaching. I thought, this man has that whole game broken down to one player. He must know everything. I bought in.

* * *

Chuck loved teaching moments, but he wasn’t an orator or a motivator. Chuck would say, “It’s not my job to hold your hand. It’s my job to take motivated people and show them how to become better.”

I recall a week in 1978, after we had lost one game and snuck by in the next. Things just weren’t clicking. By midweek we needed a jolt from Chuck—a boot up the ass. So he pulled us together after practice and said:

“Let me tell you a story about two monks who are on a journey. Some time during their journey they stop at a clearing, and in the clearing is a stream, and they stop at the stream. On the one side of the stream is a fair maiden trying to cross. And the first monk, without any hesitation, crosses that stream, picks up the fair maiden and carries her across and sets her down. The two monks carry on in silence. Sometime later on their journey they stop at another clearing. The second monk says to the first, ‘You picked up that maiden. Do you know it’s against our beliefs and our religion to come in contact and touch a person of the opposite sex?’ The first says, ‘I set her down back there, but you carried her all the way here.’ … I’ll see you guys tomorrow at 10:00 AM.”

We broke out of the huddle and walked back to the locker room and guys were like, "What the hell did he just say?" Eventually I figured it out: Our failures are back there. We move on.

* * *

Polar opposites in their approach, Noll and Bradshaw made it work on the field. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

If he was ever angry, Chuck never showed it. And if he was happy, he showed it less.

He was not a buddy-buddy kind of coach. It was difficult for him to come up and hug you. He would come around and congratulate guys on a good game in the locker room, but you could tell it was something he felt he needed to do. It didn't necessarily come natural to him.

When the Steelers hired Bill Cowher, and some of us who played for Chuck got accustomed to how Coach Cowher carried himself, we agreed that he was just about the opposite of Chuck. Chuck would never get on the field or get in anyone’s face, and he would rarely smile.

He set the tone when he was hired in 1969, while I was still at war. The story goes, he introduced himself to the team like this:

“I’ve been your head coach for the past five months, and I’ve watched every film of every practice of every game that you’ve played in over the past three years, and I can tell you why you've been losing—you’re just not any good. You have no talent, you have no authority, and you can’t cover, and you have no discipline. By the time this training camp is over, most of you will not be here.”

He had the magnificent quality of being blunt without embarrassing people. If he was disappointed, he would give you that fatherly look like, What the hell.

Mean Joe vs. Double-O

From November, the story of the epic 1974 Steelers-Raiders AFC Championship Game, which sent Chuck Noll and Pittsburgh to their first Super Bowl.

Excerpted from “Their Life’s Work,” by Gary M. Pomerantz. FULL STORY

Terry Bradshaw was more familiar with that look than anyone else. Terry was Chuck’s No. 1 overall pick in 1970, after the team finished with 1-13 in his first season. After a while it became clear that Terry wasn’t Chuck’s kind of QB. What Chuck wanted was a Roger Staubach type. We thought of Staubach, the Cowboys quarterback, the same way we think of Peyton Manning today: organized, methodical, studious, a pick-you-apart kind of quarterback.

If I say Terry Bradshaw, it brings up a whole different kind of image. Big arm, runs the ball, and when you watched him, there sometimes seemed to be no rhyme or reason to his play. From my vantage Chuck and Terry's relationship became like father and son, with Terry as the rebel kid. He and Chuck didn’t see eye to eye, but Dad was always there trying to make him the right kind of QB for his talent level.

This is how I believe it would go in the film room between Terry and Chuck:

Coach brings up a play showing the defense we’re about to play in a certain situation.

“Give me the pre-read,” Chuck would say. “What’s the defense?”

So Brad says, “Umm, Cover 2, but … you know, it could be Cover 3 … but that linebacker is up so it could be … Chuck, can you move that film up so I can see more?”

Then we find ourselves in the game in that same situation. Brad makes the call, breaks the huddle, and walks up to the offensive line with the pre-read in his mind, and he’s thinking it looks like Cover 2 but it might be Cover 3… oh screw it.

Hike! He drops back, Lynn Swann is surrounded by three players and our tight end is wide open cutting up the middle, but we don’t throw to tight ends so forget him. Brad goes to Lynn and he throws it between three guys, Lynn goes up and grabs it with one hand and pulls it down for a touchdown.

So Chuck’s on the sideline just muttering to himself, “What the hell is he … oh, that happened. OK.”

I don’t think we would have won those four Super Bowls with anybody besides Terry at quarterback. He just made things happen, and the two of them, Chuck and Terry, made it work.

* * *

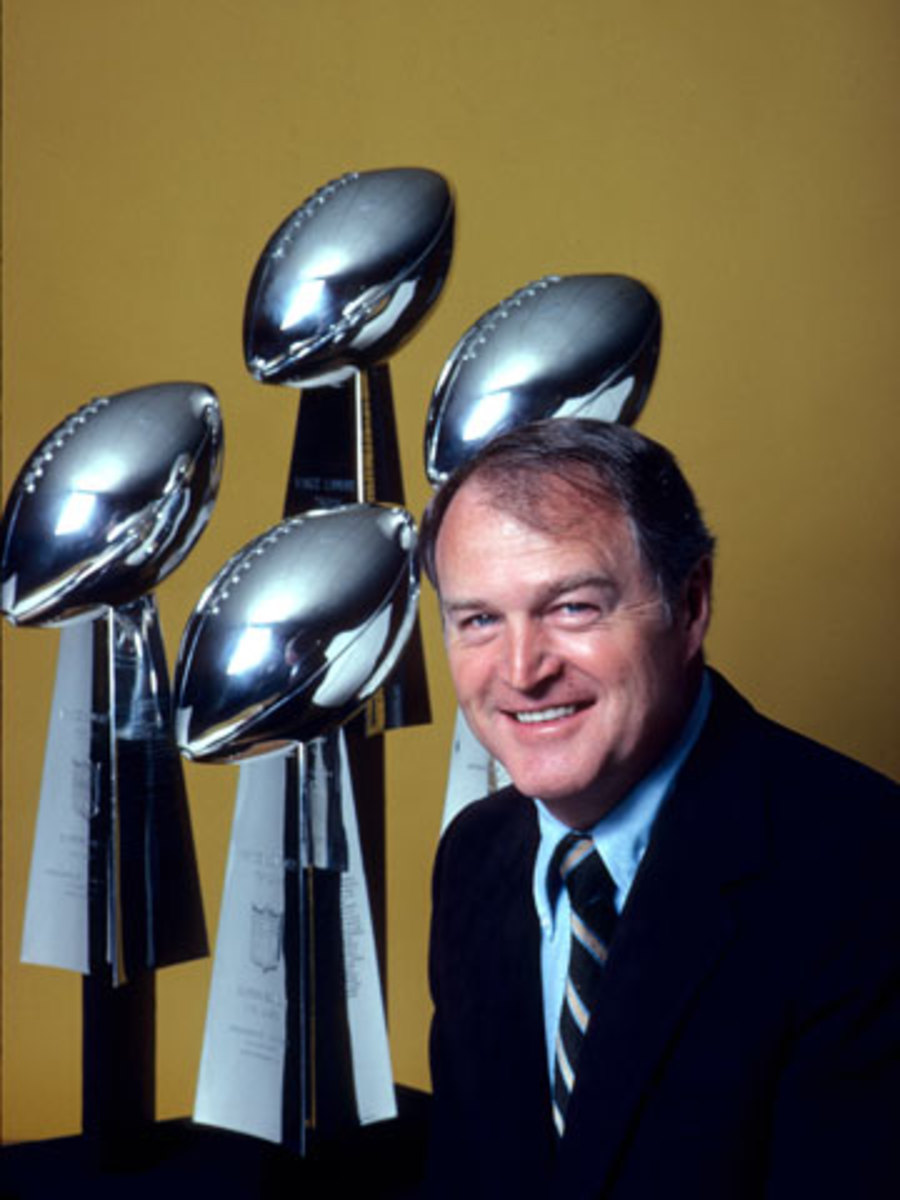

Noll with the tangible evidence of his genius: four Lombardi trophies. (John G. Zimmerman/Sports Illustrated)

Chuck was a proud man. Before he got to Pittsburgh his nickname was The Pope. Then Myron Cope, the Steelers’ radio man, nicknamed him The Emperor. The reason: He was never wrong. He always had the answer, and the right answer, to whatever needed to be done.

Coaches today will go to more experienced coaches in the league for advice. Chuck would never do that. He never would ask other coaches how they ran their offense or their defense. He wanted to be in the position to be asked how he ran his team. After I retired I worked in journalism covering the team, and I went into one of his press conferences for a sound bite. Chuck prepared his post-game press conference in his head. He would talk about the game, then his opponent, then his offense and then his defense. It could have been negative, but he never pointed to anyone or called out anyone specifically.

So every writer wants his storyline, and writers would give questions working towards the particular sound bite they wanted. And with each question, Chuck’s answers would get shorter, because in his mind he had already answered whatever you were asking about in his opening statement.

I would give him a long question to try to get the most insight I could, but his answers were always so short. All I could do was laugh.

Coach had a way of doing things, and it worked. And if you spent enough time around him, some of his way became your way. Much like the Packers talk about Vince Lombardi and Lombardi-isms, we speak in Chuck-isms. For many of us, his fundamentals of football became the fundamentals of life.

Rocky Bleier played 11 seasons with the Steelers, 10 of them under Chuck Noll, and started at fullback alongside Franco Harris in all four of Pittsburgh’s Super Bowl wins in the ’70s. He was awarded a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star for his service in Vietnam, an experience he wrote about for Sports Illustrated.