Part II: The Teacher

This is the second story of a two-part series that appeared in Sports Illustrated in July 1980. It is the definitive take on former Steelers coach Chuck Noll, who passed away in his sleep on June 13 at his home in Sewickley, Pa. He was 82. The architect of the famed Steel Curtain, Noll won an unprecedented and still unmatched four Super Bowls from 1974-79. He lorded over Pittsburgh’s sideline for 23 seasons, amassing an overall record of 209-156-1 before retiring in December 1991. Two years later, he was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The first part of the series can be read here.

By Paul Zimmerman

The date: Feb. 11. 1980. We are driving through a light snow to Chuck Noll’s house in suburban Upper St. Clair, south of Pittsburgh. It is starting to get dark, and the streets have an Old World look as we climb through Dormont and Mt. Lebanon, past the lights of stores open late, gliding over the still-used trolley tracks. Upper St. Clair is half an hour from the Steeler offices at Three Rivers Stadium, less if you take the main highway, but Noll’s wife, Marianne, says he likes to go through the towns. Noll says he once made it home from his office in 15 minutes.

As His Players Knew Him

Former Steelers running back Rocky Bleier penned a tribute to his coach, Chuck Noll, who took over a hapless franchise and, with his no-nonsense style, turned it into a four-time Super Bowl champion and one of the crown jewels of the NFL.

“That’s my record,” he says.

“What’s your slow record?”

“Two and a half hours,” he says.

“Through a blizzard.”

We drive in silence for a while. We pass a frozen pond.

“What do you think of when you see that?” Noll asks. I tell him I think of our pond at home and my kids skating and the way it looks in the late afternoon, with the mist starting to come in.

“A poet. You see it as a poet,” Noll says. “What fascinates me is the science of it. Frozen on top, strong enough to support weight, yet warm enough on the bottom to maintain life. The miracle of life.”

He stares out the window again. The pressures of the long season, of a Super Bowl that his friends say created more pressure for him than any game in his 11 years as the Steelers’ coach, seem to have almost disappeared. He spent a week at Hilton Head after the game, and he tells a story about the day he was out on the driving range, hitting golf balls.

“The pro came over and watched me for a few minutes,” Noll says, “and then he put his hand on my shoulder and said, `Relax. Calm down. The season’s over.’ ”

The Steelers had pulled out the 31-19 victory in the fourth quarter when their big-play people came up with the big plays—two long passes from Terry Bradshaw to John Stallworth, and a deep interception by Jack Lambert, who swooped in from centerfield, a place where middle linebackers don’t normally live. “Chuck’s basic strategy is to make them stop our big-play people,” Andy Russell, the retired linebacker, once said. Big-play people. High draft picks and good draft picks for the most part, matured and nurtured on the fertile teaching ground of the practice field and the film room, the products of day after day of “good learning experiences,” as Noll would say.

“Before Chuck came, our drafts weren’t really that bad—when we didn’t trade them away,” Dan Rooney, the Steelers’ president, says. “The problem was that we ran off rookies before they had a chance to show what they could do. That’s why it means so much that Chuck is so patient with them. That’s why he involves his assistant coaches in the scouting, so they’ll be committed to these kids.”

“I think Chuck is unique in that he doesn’t fit that winning-is-the-only-thing coaching philosophy,” says Upton Bell, who was head of player personnel for the Colts when Noll was an assistant to Don Shula. “With him, teaching is the only thing, developing a man to fulfill his potential. If he does a good teaching job, winning is the natural by-product. In a world that looks for conformity. Chuck is a different type of human being; he’s not as interesting as a coach as he is as a human being.”

“Chuck and I started out coaching together,” former Oakland Coach John Madden says, “and I thought he’d get out of it before I did. Maybe four years ago Chuck said to me, `John, you’re going to be in it for the rest of your life. This is perfect for you. I’m going to get out of it.’ It started me thinking. Is this really all there is to life? I’d never thought about it before. And now look, I’m out of it and Chuck’s still in it.”

But how many teachers get such tangible rewards, see such immediate results? How can you quit when you keep turning out Rhodes scholars? “The one nightmare I always had was going into a game unprepared,” Noll says. We were turning onto Noll’s street now, a quiet thoroughfare in an unpretentious neighborhood. A college professor’s neighborhood. “I can’t pinpoint it, but if I allowed fear to come into what I’m doing, that would be my greatest fear—having spent time on the wrong thing.”

He pulled into his driveway. A layer of snow covered the walk leading to his house, and I asked him if he were expected to shovel it.

“The Lord giveth,” he said, “the Lord taketh away.”

There is nothing in Noll’s house to indicate that his profession is football. No lamps made out of helmets, no football pictures on the wall, no game balls in glass cases. “The only football stuff we have is in packing cases downstairs,” Marianne says. “When we first moved into the house,” son Chris says, “it was painted a dirty brown color. My mother and dad were standing in the front yard trying to decide what color to paint it, and they settled on yellow with black trim. I said, `Oh, boy, the Steeler colors.’ They both said, `Oh, my God.’ They hadn’t thought of that. The next week we had a green house.”

Teaching is the only thing, developing a man to fulfill his potential. If he does a good teaching job, winning is the natural by-product,” said Upton Bell. “In a world that looks for conformity. Chuck is a different type of human being; he’s not as interesting as a coach as he is as a human being.

On the Sunday night before Christmas last year, Lynn Swann and his wife and sister, Terry Bradshaw and his wife, and Gerry Mullins and his girlfriend (now his wife) went out caroling. They ended at Noll’s house. He invited them in. It was the first time they had seen the inside of the house.

“Chuck came downstairs,” Swann says. “He was wearing a sports shirt with the sleeves unbuttoned, casual slacks. He had a guitar with him, `to get us in tune,’ he said. We stayed there maybe two hours. He played the guitar. ... He put on glasses to read the music. We never knew he could play. He had some pictures on the wall, photographs that he had taken of wildlife, one of a female bird nesting. A rare bird. Mullins knew it right away. I saw before me not the head coach of the Pittsburgh Steelers. I saw a side of him not many of us had seen before. There was just so much warmth in that house. That one night ... I’ll remember it 50 years from now.”

But still, it had taken them all those years to get inside his house. “How many times have you been to your boss’ house?” Bradshaw asks.

“There’s a very good reason why a coach can’t get too close to his players,” Lambert says. “How can you get to be friends with a guy and then have to say, `Hey, Jack, you’ve given me six good years, now I’m trading you.’ ”

Noll’s diversity of interests is a problem for the people who have to rely on him for daily quotes and who find him so closed. How can this diversity exist in such a hardhead, a man who constantly reminds us, “The public does not have a right to know everything.” Noll’s attitude has led to a measure of cliche writing, the encomium “Renaissance Man” being the favorite of those who can’t think of anything else to say about him. Occasionally, there’s some questioning. He flies his own airplane and scuba dives: loves baroque and chamber music, haute cuisine and fine wine; keeps up on oceanography and the biological sciences. How can it be? Is there, perhaps, a soft spot in that mass of knowledge, some weeds in the garden?

“One thing a guy wrote in a Boston paper really griped me,” Chris says. “The guy wrote that the more he talked to Chuck Noll about wines, the more he realized Noll didn’t know the difference between a Ripple and a Burgundy. I hit the roof when I read that. I mean, I can remember going up to the Napa Valley and touring the vineyards with my parents when I was six.”

The truth: “I developed a love for California wines when I worked as an assistant coach in San Diego,” Noll says. “We used to drive up to Escondido to buy a dry muscat this family made; they used to come right out of the kitchen and sell it to us for 55 cents. It had the taste of a spice, of cinnamon. I’ve gone back there looking for the place, but it’s not there anymore.”

Noll’s cellar at home is fortified with wines he has picked up on California trips. You’d import them, too, if you lived in Pennsylvania, with its state Liquor Control Board system, where they spell wine with an ‘h’ in it. Noll’s very big on Chardonnays and on Cabernet Sauvignons. It’s a working cellar, 100 or so bottles stored in drainage tiles, which keep the temperature constant; it’s for joyful drinking, not collecting, although Noll is saving some 1971 Chateau La Mission Haut Brion and a couple of cases of Beaulieu Vineyards’ 1970 Private Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon, a wine that he bought for $10 a bottle and that brought $980 a case at last year’s Heublein auction.

On cookery: “People have a misconception about that,” Chris says. “He doesn’t do all the special cooking in the house. My mom’s too good a cook for that. But he’ll take charge of the sauces. He’s got a natural talent for it; he could be a saucier in a fancy restaurant in a minute. Loves garlic, loves tarragon. He’s got a thing about omelets, too.”

“You can get a reputation as a great cook by perfecting only two or three dishes,” Noll says. “Just make sure you keep inviting different people to eat them.” Noll enjoys good food—and not in tiny amounts. As A.J. Liebling said, “Any food worth eating is worth eating a lot of.”

“When I was little I was a very slow eater,” Chris says. “Dad was very fast. He’d be finished in a minute, and when I’d stop for a rest, he’d say, `You don’t want that, do you?’ and he’d reach over with his fork. It annoyed me. Once I waited till he did it, and then I let him have it right in the hand with my fork. Pow!”

People ask me why I look at football films so much,” Noll said. “Every time I go over them I see a new thing. You can look at the same one 20 times, and then all of a sudden something will jump out at you.

Noll’s love of music goes back to his Cleveland Brown days, when he was a regular at the Cleveland Orchestra. On his coffee table at home this night was a recording of a Telemann Trio Sonata for Recorder, Viola da Gamba and Continuo, by the Manhattan Recorder Society. An old favorite. “I bought it in Kalamazoo, Mich., on a scouting trip when I was with San Diego,” Noll says. “I started playing the recorder myself, and when I’d tell someone, they’d say, `Oh, you play the recorder? What speed, 33 rpm?’ ”

One lesser-known fascination of Noll’s is roses; he had a formidable rose garden at his home in San Diego. “When we went back one year and looked at our old house,” Chris says, “the people had ripped the rose garden out and put in a swing set. That really hurt him.”

The love of oceanography was born from a casual snorkeling venture with Chris in the Florida Keys. “I got excited the first time I looked down there,” Noll says. “So much life to be discovered. Discovery—that’s the thing that excites me. A new restaurant, an island in the Caribbean, it’s all part of the same thing. People ask me why I look at football films so much. Every time I go over them I see a new thing. You can look at the same one 20 times, and then all of a sudden something will jump out at you.”

As for Noll’s political views, his son says, “He has very firm beliefs, but if you’re going to argue with him you’d better be on solid ground, because he reads everything. Sometimes I disagree with him, but I’m not always sure enough of myself to argue it. A few months ago I asked him which candidate he was interested in right then. He said Connally. Right there I disagreed. I think he voted for Carter last election. He liked his record in Georgia, the way he redid the government and cut down on the bureaucracy. I don’t think he feels Carter has done the same thing in Washington, though.”

“Chris said I voted for Carter? I’m not so sure,” Noll says. “I’m certainly not one-party oriented. I think people have misinterpreted my politics. In the first place, politicians deal in words, in leadership through rhetoric. I’m not in that business. But if you want to know what I’m against, it’s handouts—getting too much in front.”

In football, one NFL coach says, “You’re in the reward and punishment business. Things that come easy are unproductive. That’s why most football coaches are basically conservative. Besides, what did Chuck Noll ever get that he didn’t earn himself?”

A fine God-given mind, for one thing. The disposition and inclinations of a teacher—the 5-year-old who started school a year early because “I couldn’t wait.” And a penchant for cutting through stereotypes. When the world was switching to big, tall offensive linemen, Noll went to smaller, quicker guys, people who could think on their feet, who could make a trap-block offense go. He wanted his linebackers quick, for pass coverage. Weight could be added later. Maybe he saw himself in both those positions—the little, quick guy who could think. Rival coaches admire the ability of Noll and his staff to get the utmost from raw talent—players from the black schools, for instance, who had never been exposed to sophisticated coaching. And once that talent got to the Steelers, there were no complicated behavior codes to restrict it. The Steelers have always had an open locker room; the assistant coaches have been free to talk to whomever they liked; the players haven’t been given any rigid rules of dress.

“As long as a guy is presentable, it doesn’t matter to me how he dresses,” Noll says. “Beards and mustaches, what kind of haircut you have, aren’t important. Remember the old image? A crew cut denoted a big, dumb guy who couldn’t think, couldn’t act. Fashions change.” And Noll has never accepted the idea that everyone must be treated alike. “There are 45 different personalities on a team, each of them unique,” he says. “How can you deal with each one the same way?”

“Joe Greene always got special treatment; it was as if Chuck made him his special project,” says Ray Mansfield, the retired Steeler center. “Chuck played it just right with him. You’d see Chuck in the locker room, talking head to head with Joe, maybe with his arm around him. Then one day Chuck just cut him loose. He chewed him out, fined him for something. You’re on your own now, buddy. It was like the momma bird shoving the chick out of the nest. And Joe flew.”

When the world was switching to big, tall linemen, Noll went to smaller, quicker guys who could think on their feet and make a trap-block offense go. He wanted his linebackers quick, for pass coverage. Maybe he saw himself in both those positions—the little, quick guy who could think.

“You have to understand what Joe was when he first came to the Steelers, and then what he became,” Andy Russell says. “When he joined the team he was an emotional mess on the field. He didn’t have a hold on himself. It was all peaks and valleys. Chuck tried to teach him that when you get yourself on a nice, even plane, you’ll be a much better player. And Joe turned into the most devastating player of the decade. I mean, there were times when he single-handedly won games. You’d be late in the fourth quarter, the score close, everybody so tense you couldn’t breathe, and Joe would come into the huddle and say, `O.K., we’re gonna do it now! Right now! This play! It’s take-a-way down!’ And he’d do it. He’d go through bodies and get to the football and strip it away. You’d see it in the films afterward, and you couldn’t believe it. You’d say, `Hey, run that back again.’ Anybody with intelligence knows that a player like that can’t be treated the same as everybody else.”

Noll the teacher has tended to over-shadow Noll the innovator, mainly because Noll himself tends to downplay innovation. “If I had to choose between a coach who’s a strategy guy and one who’s a teacher, it’d be no contest.” Noll says. “I’d take the teacher every time.” But they can go together. The tackle-pinch defense of 1974, which aligned Greene, the left tackle, in an almost sideways stance, angling in at the center, while Right Tackle Ernie Holmes played the center straight up, came from a desire to make maximum use of Greene’s great quickness. It helped the Steelers amass a phenomenal defensive record through the three-game postseason set, ending with the 17 yards rushing to which they held the Vikings in the Super Bowl.

Afterward, someone asked Noll if the pinch defense would now become a fad. “Sure,” he said. “All you have to do is find another Joe Greene.”

The Steelers threw three big offensive innovations at the Rams in the last Super Bowl: the hitch-and-go pass out of slot formation that gave John Stallworth those two big catches in the fourth quarter; the 32-yard pass to Franco Harris that set up the first field goal, in which Harris sneaked out from a position outside the guard; and the pat-and-go quick snap to Bradshaw that worked twice and kept a drive alive in the third quarter.

In 1978, when defenses were cheating up and stopping the Steelers’ ground game, Noll switched gears and opened up the offense. Why the heck shouldn’t he? He had the guys to make it work—Bradshaw, Swann, Stallworth. And hadn’t he broken in as a coach under the Chargers’ big-play system—Hadl to Alworth, bombs away, release the pigeons and on with the games?

“But the key to everything was teaching.” Russell says. “You’d see him being stopped by some rookie after an afternoon practice during two-a-days, a kid he’s got to know is going to be cut in a matter of days. The kid would say, `Coach, I’m having trouble with this technique,’ and Chuck would spend half an hour with him. I think he enjoyed it more than coaching the superstars. He just loves to teach.”

The dark side of the picture is Bradshaw. In 1971, Bradshaw’s second year, Noll brought in the first and last quarterback coach he’s ever had, Babe Parilli, his old roommate on the Browns. Two years later Parilli was gone, and Noll took over the job himself. Meanwhile, the Steelers had drafted a young quarterback out of Tennessee State. Joe Gilliam, to battle Bradshaw and Terry Hanratty for the starting job. Three young quarterbacks on one club, a tricky situation, but, oh, what talent Gilliam had. How could you pass him up?

“When I was a ball boy in camp.” Chris Noll says, “I’d fool around with Joe Gilliam, running sideline patterns for him. He’d lay it out there 30 yards on a line, every one on the money—and he’d throw it behind his back!”

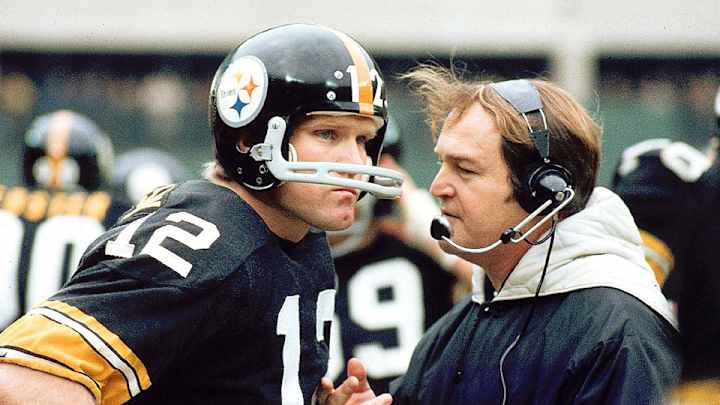

In 1974, the Steelers’ first Super Bowl year, Gilliam started the opening six games. He’d been the quarterback in camp during the strike, and he’d looked better than anyone else when the veterans came back. He was benched for the seventh game. Gilliam’s idea of an offense was five minutes of game plan, then put the ball up. Bradshaw started the next three games. Hanratty the next, and Bradshaw came back to finish the season. Noll’s quarterback meetings were a nightmare for him. When Bradshaw would come out of the game after throwing an interception, Noll—lips tight, eyes blazing—would meet him on the sidelines. Rage. Bradshaw is one of the few Steelers in Noll’s 11-year career ever to get such treatment. Why the hell wasn’t he learning faster? Why, dammit?

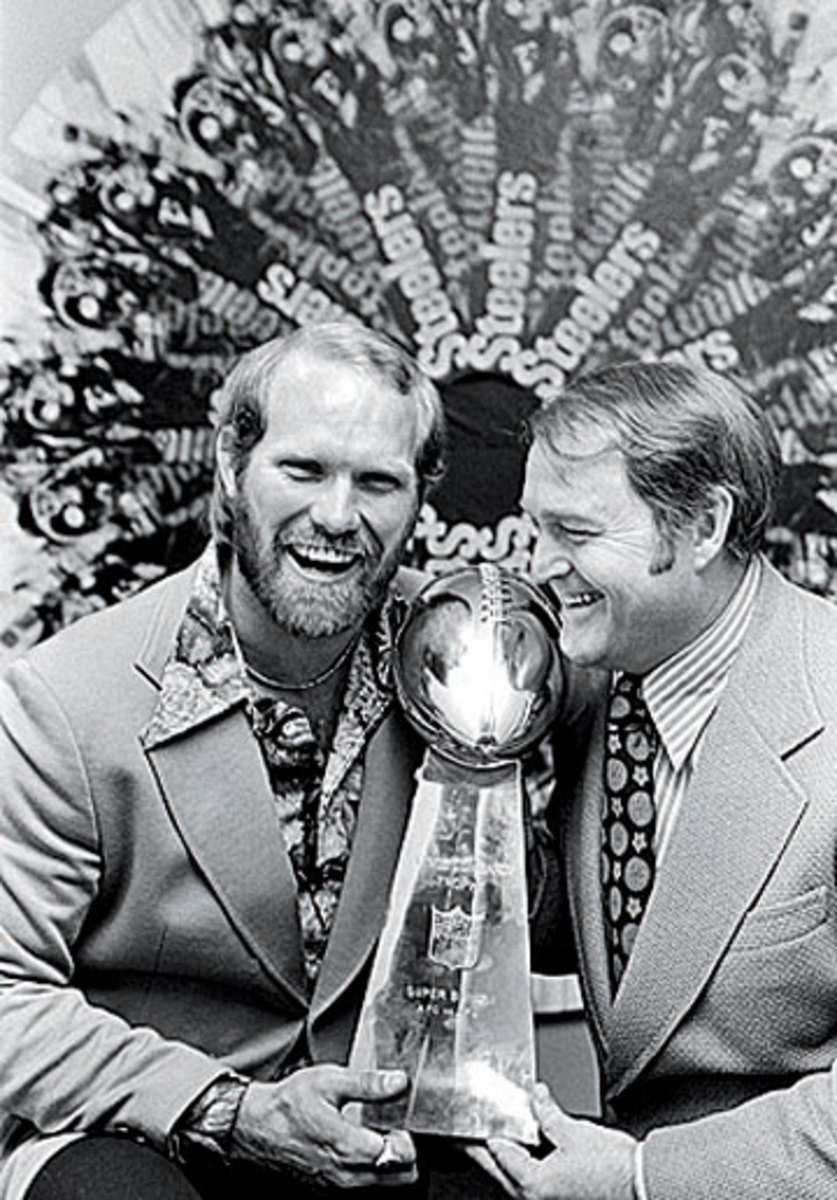

Bradshaw and Noll with the Lombardi Trophy following a victory parade through downtown Pittsburgh in January 1975. (AP)

“It was funny watching the three quarterbacks come out of the quarterback meetings,” says Tom Keating, a former Steeler defensive tackle. “Bradshaw would look whipped, Gilliam would look mad, and Hanratty would just be smiling and shaking his head. I’d come from Oakland, and when John Madden would yell at Lamonica or Blanda, they’d yell right back. But with Noll—never.” Hanratty says. “I think Chuck so badly wanted Terry to be great—he wanted him to just win the job flat-out and end all the turmoil—that he lost his head. Have you ever seen Shula going toe to toe with Griese like that? Or Landry with Staubach? And Terry’s better than all of them. When I made a mistake, Chuck never chewed me out: maybe he didn’t feel I’d been around that long. I told Terry 100 times, `Tell him to go to hell. You’re the quarterback.’ But Terry would shake his head and say, `No, no, I can’t do that.’ To this day I don’t think it’s settled.”

“Our relationship has changed,” Bradshaw says. “When I was young, I was in awe of him. All that power. I feel that in the last few years I’ve gotten to know him. I know he’s very concerned about me as a person, my private life, football. He’s very proud of what I’ve accomplished. Everything is magnified with him. When he smiles at you, you know you’ve really done something.

“I don’t think he handled me properly, but he didn’t know me. I wanted to be handled very personally, like I’d been in college. He could have made it a lot easier. There were times he dressed me down in front of the team; once he fined me $25 for missing a pregame meal, and I was there three minutes late. I was outside talking to one of the Steeler scouts.

“It was a rough road, a testing ground. But I think he felt I could handle it, that I was going to be the kind of championship quarterback he needed. He wasn’t going to baby-sit. I remember once going in and asking to be traded, and he said, `You’re going to be a great quarterback someday. It takes time.’

“Well, I came through it, and now I’m much closer to him. He’s very loyal to his players and the people who work for him. He’s the most loyal human being I’ve ever met.”

The relationship with Bradshaw is a hard thing for Noll to discuss. The end product is there for everyone to see, the greatness of Bradshaw as a player and a competitor, but it was one of the few times Noll’s ability as a teacher was strained. “I always wanted Terry to be a leader.” Noll says, “but you can’t just tell someone to go out and lead. You become a leader by doing. The trouble is, in our society many political leaders lead by talk, by air. That’s why football’s so different. You can talk all you want, but whatever you say means nothing until you’ve done something.”

The same philosophy carried over into the way Noll raised his son. He wanted Chris to learn and grow by experiencing things. Scuba diving, bird watching—they were all methods to bring the family closer, to give them common experiences. Chris played a little high school football and kicked extra points for a while at Rhode Island, but then switched to soccer, which he coached this season. Noll never pushed football on his son, never urged him to compete, but he didn’t deliberately try to steer him away from pressure situations.

Chuck Noll,” said Father Benedict Sellers, a teacher at Noll’s high school in Cleveland, “has been given by God the ability to lead men to victory after victory. He’s humble about this gift. In a different era he would have been a great battlefield leader, certainly a great religious leader.

“Chris might have had a problem living with my image as a successful coach.” Noll says, “and he might also have had a problem being an only child. When you have a brother and a sister, there’s a natural competition. When you don’t, then you compete with your mother or father. It makes it tough for a parent to keep from being overprotective, from trying to remove pressure situations.

“I know people who say, `I want to keep my kids from ever being in a pressure situation.’ What a terrible thing to do to a kid. You wind up with someone who’s leaned on other people to make the decisions for him. All of a sudden he’s an immature kid of 26 who’s never solved a problem in his life. We don’t try to keep our son from stressful situations.”

In his home in Rhode Island. Chris pointed to an old Steeler poster in his room and a Steeler mirror next to it. “It’s funny, until this year I couldn’t put them up,” he said. “I’d always known my father as, well, Dad. We had fun together, even though discipline around the house was tight. I think I must have resented what he was. I’d be introduced to someone in high school and they’d say. This is Chris Noll.’ And two minutes later. `He’s Chuck Noll’s son.’ I think that’s one of the reasons why I went to Rhode Island and not Penn State.

“I’d ask my father football questions from time to time, but they were only fans’ questions. I think I had trouble handling who my father was. When I was little, I’d resent his coming home late every night. I’d eat at six o’clock. I wouldn’t wait for him. It used to bug me that during games David Shula would stand next to his father on the sidelines with a clipboard, while I’d be down with the ball boys. I asked my father about it, and he said, `Because David has an interest in football.’

“But in the last year I’ve been able to see my father as a whole person; I’ve been able to appreciate his accomplishments. Do you know that when his sister’s husband died 17 years ago, he took on responsibility for the whole family? I’d bring friends to the house and they’d say, `Gee, he’s just like anybody else.’ I can understand how his whole life has been devoted to sharing everything with his family. Once, after I’d just borrowed some of my dad’s favorite stereo records, I told my cousin, `I feel bad. I take his music, his wine, his money, everything he has.’ My cousin said, `He wants to share with you.’ Once, on my birthday, my father opened a bottle of 1966 Chateau Margaux; I found out later that he had a cold and couldn’t taste it, but he never let me know. I can bring people over and he’ll open any bottle of wine he has in the house—except his 1970 BV Private Reserve Cabernet.”

People who haven’t been around Noll long have trouble understanding the paradoxes. At times he’ll show the utmost patience, at other times he can move swiftly and decisively, almost ruthlessly. After Noll’s first season in Pittsburgh, he got rid of Roy Jefferson, one of the team’s few stars, because he read Jefferson as a disruptive influence. The same with Preston Pearson five years later. Yet, he could look the other way when cornerback Mel Blount threatened to sue him for slander in 1977; the affair was smoothed over, and Blount is still making the Pro Bowl as a Steeler. And when Ernie Holmes took a shotgun and a revolver out on an Ohio highway in 1973, fired at passing trucks and a police helicopter and was arrested for assault, Noll drove to the Mahoning County Jail in Youngstown the next morning to try to straighten things out; Holmes later was a key performer in Pittsburgh’s first two Super Bowls.

People who are aware of Noll’s absolute control of the Steelers are surprised to find he runs an open operation. When Keating joined Pittsburgh in 1973, he couldn’t get over the fact that everything was announced at the team meetings—all the squad moves, the personnel changes, everything. Says Keating, “Chuck would stand up and say, `We picked up so-and-so on waivers today. We feel he can help the club.’ When I played in Oakland, in Pride and Poise Country, the only way you’d know about a move was to read it in the papers.”

But when Keating was released in 1974 after the strike, after he’d been an officer in the Players Association, his views were different. “With Chuck,” he said then, “it’s my way or the highway.”

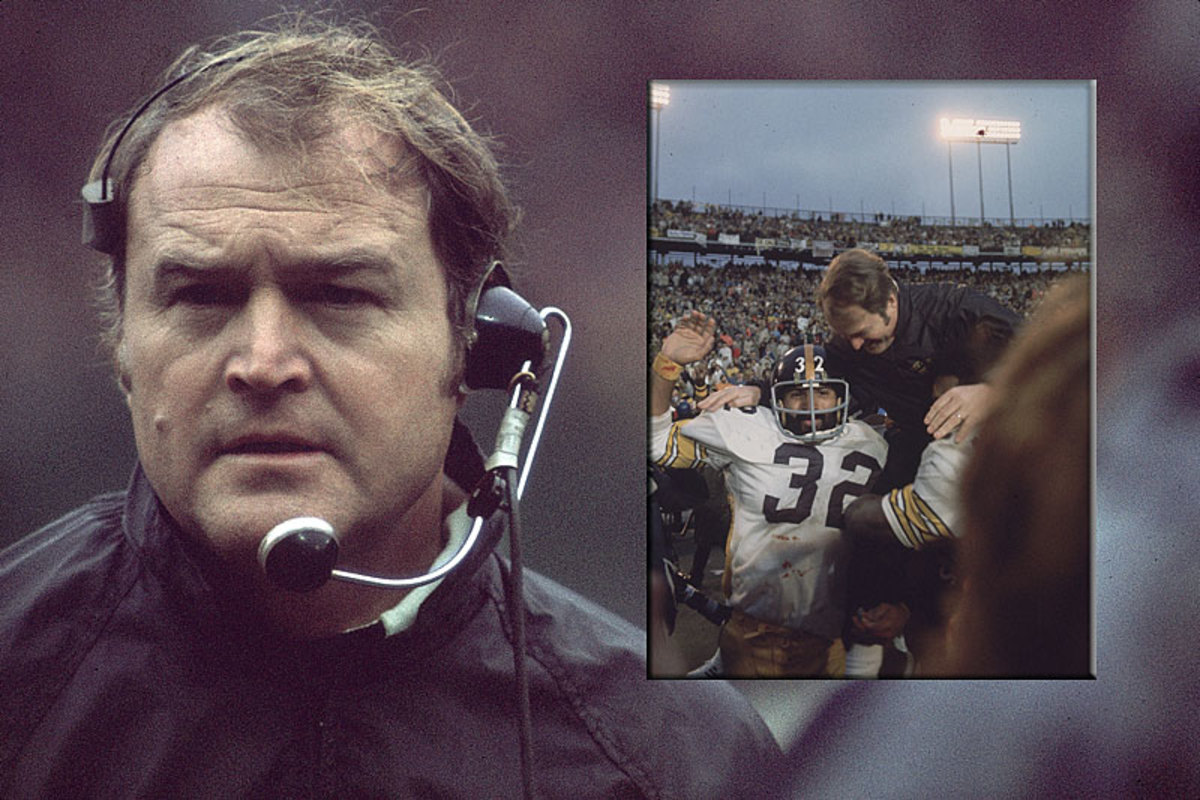

Noll coaching against the Browns in 1973 (l.) and getting carried off the field by Franco Harris (32) and Mean Joe Greene (75) after beating the Vikings in Super Bowl IX in January 1975. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

In 1978 John Clayton of The Pittsburgh Press broke the story that the Steelers were dressing their rookies in pads during off-season practices. This was clearly a violation of the NFL’s collective bargaining agreement with the players and cost the Steelers a third-round draft choice. Noll, in a show of anger, said, “The story had no news value whatever. The only way I can read it is as espionage.”

“Reflecting on that incident,” Noll says, “I made no attempt to hide that practice session. It was a silly rule and the league knew how I felt about it. Anytime you’ve got people going full speed on a football field, they’ve got to wear pads—for their own protection. My views weren’t any secret. But it was written as if I’d tried to put something over. The writer didn’t call me about it to hear my explanation. He simply called the league and said, `What are you going to do about it?’ Then he asked Ed Garvey [head of the NFL Players Association] the same thing. That’s why I got upset.”

Noll’s assistant coaches represent another paradox. When Noll got the Steeler job in 1969, 16 of his 37 years had been spent in pro football, as a player and coach. But in hiring assistants, he has leaned more and more toward people without any professional experience. He felt that college people are more likely to be teachers, and he wanted men whose minds were free of other NFL systems. He got away from that idea a little when he hired Rollie Dotsch, with seven years’ experience as a pro assistant, as his line coach in 1978. But Dick Hoak, the offensive backfield coach, is the only Steeler assistant who played in the NFL, and Noll’s two defensive assistants, George Perles and Woody Widenhofer, who have been with him through all four Super Bowls, came straight from the colleges. No member of Noll’s staff has become a head coach, even in college. The biggest shock came when Perles, with all those Super Bowl wins behind him, applied for the Michigan State job this year. Everyone thought Perles was a lock, but he was turned down in favor of Muddy Waters from Saginaw Valley College.

“I don’t know the answer,” Noll says. “There are guys on this staff who are fully ready to become head coaches. I wish I knew why they aren’t. It’s a nagging thing.”

Noll and his assistants form a tight little band; they socialize together, eat together, play poker together. They have their own vocabulary—”velours,” for instance, are poker hands that are absolute mortal locks. After every Super Bowl, Noll and his staff and their families take a 10-day vacation; twice they’ve gone to the Bahamas, twice to Acapulco. And together they’ve made history.

History. The inexact science that has received so much of Noll’s scorn. Ever since Noll’s second Super Bowl win, in 1976, people have asked him: How will history evaluate the Steelers? Are they really a dynasty?

“Can’t tell now,” Noll says. “It’s like sainthood. You have to wait 10 years.

“This whole area of historic evaluation bothers me. It’s not so much that I dislike history; it’s just the interpretation of it that screws everything up. It’s always the way they see it, as opposed to the way you see it. I remember once we double-dated with Marianne’s roommate. The next day I heard her talking about the party we’d been to; I had a hell of a time recognizing that party from her description. One of the best things in Sandburg’s biography of Abraham Lincoln is his description of the second Inaugural Address and the various editorial comments that followed. They were so different. It was amazing that so many people could read such different things into one speech. It comes back to the same thing. You hear what you want to hear. It’s the same in teaching. You think to yourself. `Boy, I did a great job teaching today,’ but it’s no good if the words fall on infertile ground. It’s teaching, plus the common repeated experiences, that make the whole thing work.”

So, how do we evaluate Chuck Noll, a basic person and something of an intellectual, too? A man who inspires reverence in the people who work for him. “He’s brilliant,” Perles says. “I could never be as good as he is, and anyone who thinks he could hire one of us to be as good as Chuck is whistling Dixie.”

And yet Noll is a man who can make you uneasy. “You know how it is sometimes when you’re around a guy you’re comfortable with,” Artie Rooney says. “You could say five stupid things, and you’d think, `Boy, I’m dumb to say that.’ But it’s O.K.; you know he still feels you’re a nice guy. Around Chuck I always feel that I have to watch myself, that I don’t want to say anything stupid. I mean, I like Chuck, but being with him is almost like being with the toughest professor you ever had in college.”

“I’ve kidded with him at times,” Swann says, “but no one kids around with Chuck all the time. You pick your moments, and if you haven’t picked a good one, he’ll just look at you with no expression and you’ll find a way to nod your head and back away.”

“Chuck Noll,” says Father Benedict Sellers, who teaches Latin and French at Benedictine in Cleveland, where Noll went to high school, “has been given by God the ability to lead men to victory after victory. He’s humble about this gift. In a different era he would have been a great battlefield leader, certainly a great religious leader.”

Don Shula and George Allen once were asked to give capsule portraits of themselves as coaches, to put in a few words the way they would like to be remembered. Each man gave it considerable thought.

“Fair-minded,” Shula finally said. “Tried to do things with class. Never knowingly screwed anybody.”

“I want to be remembered,” Allen said, “as a man who wanted to win so badly that he’d give a year of his life to be a winner.”

The same question was put to Noll recently. He smiled. Again, the interpretation of history.

“A teacher,” he said. “A person who could adapt to a world of constant change. A person who could adapt to the situation. But most of all a teacher. Put down that I was a teacher.”