The Accidental Coach of the Cleveland Browns

BEREA, Ohio — Mike Pettine certainly looks the part. He’s got the bald head, the goatee and the muscular build. He’s a defensive coach who used to go get (bleeping) snacks with Rex Ryan. About the only thing missing from the football meathead ensemble was a T-shirt from Jay Glazer’s new MMA training center.

And then the 47-year-old Pettine opened his mouth, laying waste to every preconceived notion you might have had about the Browns’ new coach.

Cleveland, you might be on to something here. I must admit I was little skeptical about Pettine getting the job. In my mind, a lot of his success had come from the defensive scheme born of Ryan. And I’m always leery of people who climb the ladder fast and seem a little too eager in the process. Just 13 years ago, this son a of a Pennsylvania high school coaching legend was trying to make a name for himself roaming the sidelines of North Penn High School. Look at him now, sitting in one of the Browns’ Google-like offices with a glass door next to owner Jimmy Haslam. That just doesn’t happen.

According to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, Pettine is the first high school head coach to ascend to an NFL head coaching position since Dick Vermeil last coached the Chiefs in 2005. Vermeil, however, was a head coach on the junior college level and at UCLA between coaching high school in 1962 and when the Eagles hired him in ’76. Pettine’s recent résumé includes stints as the Ravens’ outside linebackers coach from ’05 to ’08, the Jets’ defensive coordinator from ’09 to ’12 and the Bills’ coordinator last season.

Pettine was hired as coach in late January, about three weeks before owner Jimmy Haslam fired the team's president and GM. (Diamond Images/Getty Images)

Pettine wasn’t even supposed to get the Browns’ job. Forget the fact that he was about the 35th person offered the job after Haslam fired Rob Chudzinski after one season into a five-year contract. The only reason Pettine even took an interview was because his agent, former NFL end Trace Armstrong, urged him to get experience for next year’s job hunting season.

Now Pettine is sitting in the same proverbial chair that Paul Brown, Blanton Collier, Marty Schottenheimer and Bill Belichick did. Who does this guy think he is? Trust me, Pettine knows what we’re all thinking—and he’s using it to his advantage.

“Being a high school coach recently, that's how people perceive me,” Pettine says. “I maybe exaggerate that in my head, but that helps me, with a little bit of a chip on my shoulder: Yeah, you're just a high school guy.”

Those with such a narrow view of Pettine will be surprised. I certainly was when I spent a recent afternoon with him talking about his team-building beliefs, scheme concepts, leaked playbooks, switching jobs, organized chaos, learning buddies, the sponge theory, inventory of techniques and why the Browns will vary their offensive tempos.

Pettine, I realized, is the exact opposite of a football meathead.

* * *

Pettine knows he’s not exactly stepping in a bare-cupboard situation. The men who hired him and were ultimately fired, Joe Banner and Mike Lombardi, did a good job of setting up the Browns for success with draft picks, trades and cap management. “If you look at the Browns' film from a year ago and just watched them, you'd say there's no way they only won four games,” Pettine says.

But the key to a revival this fall will come on defense. Play well on that side of the ball, limit turnovers on offense and suddenly you’re in every game. That’s why the Browns were content to go the slow route with the quarterback position, until they traded up four spots to land Johnny Manziel in the first round of this year’s draft. Pettine and general manager Ray Farmer want to follow the path blazed most recently by the Seahawks and the 49ers.

We felt this entire draft class, every single quarterback needed a redshirt year, with Johnny really being the only one that had a chance to be an opening-day starter,” Pettine says. “It could happen, but in my ideal world, it’s not opening day.

“That was our point all along, let's build the best team first, let's not take the quarterback,” Pettine says. “There was so much pressure internally to take a quarterback with the fourth pick [but] we weren't going to do it because the grade didn't justify it; we weren't going to draft for need.

“My point was, I hope we're not drafting fourth again anytime soon. Let's look at the model. If you don't have that guy, then you need to build it like Seattle did, like San Francisco did. Get a guy with some unique traits, but first and foremost, he's not going to lose the game for you. Building a great defense and offensive line so we can run the ball—the quarterback’s going to look good because you're not going to be in third-and-8, you’re going to be in third-and-4. Percentage-wise you're going to convert more. Then ask the guy to make a couple plays with his feet, complete a fourth-quarter comeback half the time. Next thing you know, you look up and you're pretty damn good.”

Manziel certainly possesses unique traits, including a rare playmaking ability for the position, but he’s never been described as an astute game-manger. Even Pettine’s own evaluation of Manziel as a prospect stated, “He has a tendency to keep both teams in the game.” He could be a polished game-manager in the future (Brett Favre was similarly reckless early in his career), but Manziel is very much a work in progress in that area. That’s why there are no plans to rush Manziel, especially with the season-opener at Pittsburgh against coordinator Dick LeBeau’s zone blitz defense. They don’t have those in the SEC.

“We felt this entire draft class, every single one of [the quarterbacks] needed a redshirt year, with Johnny really being the only one that had a chance given the right circumstances to be an opening-day starter,” Pettine says. “It could happen, but in my ideal world, it's not opening day.”

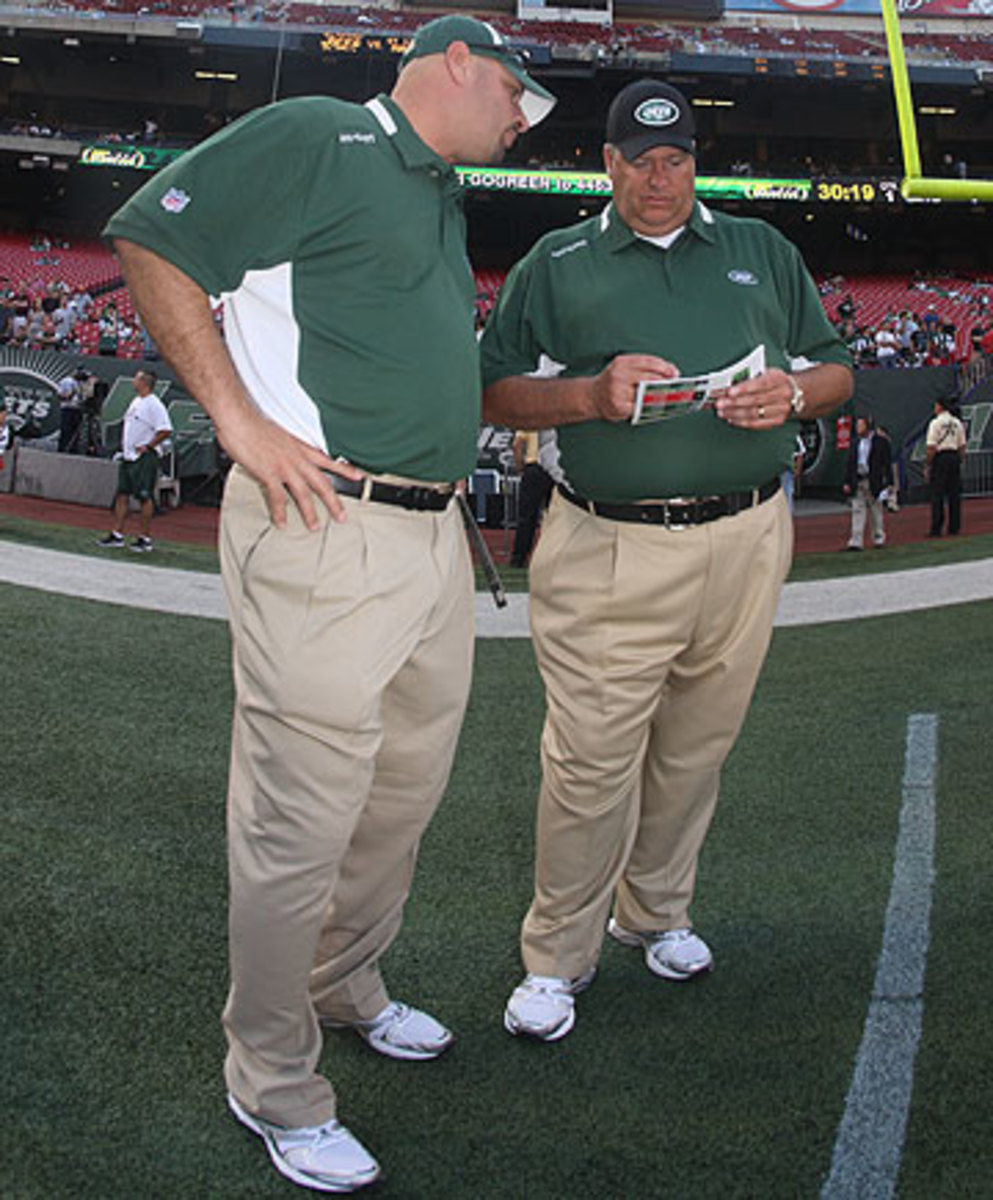

Pettine worked on the same staff with Rex Ryan for 11 seasons, first in Baltimore and then with the Jets, until taking the Buffalo defensive coordinator job in 2013. (David Drapkin/AP)

So back to the defense, which will have a big say in the final result of Pettine’s first season. As a football junkie, this is the real reason I traveled to Berea. I have loved watching the Ryan-Pettine scheme operate, especially against the best quarterbacks in the game. There’s no better scheme in today’s NFL. Just go look at what the Jets have done since Ryan’s arrival, what Pettine did in Buffalo last year, and what former Jets assistant Bob Sutton did with the Chiefs last season. When I watch the system operate on the coaches film cut, I see organized chaos. Every pre-snap look is different from the ensuing coverage and pressure on the play. That messes with the best quarterbacks, who are elite because they win before the snap deciphering the defensive scheme they are about to encounter.

But how does a defensive coach get his players to do that? How will Pettine and defensive coordinator Jim O’Neil be able to get the Browns up to speed in their first season? Surely it’s way too complicated for that to happen.

Not the way Pettine and O’Neil teach it, which seems to be the key to the system.

“I think it's happened quicker here because I think it's a smart group,” Pettine says, comparing the install to last season’s with the Bills. “I'm not saying we were dumb in Buffalo—far from it—but this is a group that I think processes, as a whole, very quickly.”

The way Pettine teaches has a lot do with that.

It starts with the coaches. The players can’t learn unless the coaches know it inside and out. O’Neil, linebacker coach Chuck Driesbach, assistant linebackers coach Brian Fleury and defensive line coach Anthony Weaver are all veterans of the system, at least back to Buffalo. Assistant defensive backs coaches Bobby Babich and Aaron Glenn, and secondary coach Jeff Hafley, were new to the system. Before the players arrived in the building, O’Neil installed the scheme with the coaches using five years of teaching tape (the best execution of scheme and technique from the Jets and Bills). But there was a lot of give and take, and the newcomers were free to question the whys and hows of the scheme.

“They were able to refine it even more and make it more player-friendly from the beginning,” Pettine says. “I think anytime you can install anew, if you can step back instead of just blowing the dust off, here it is, to look at it again and see if it still continues to make sense—they did a good job.”

The initial playbook itself is actually quite thin, and that’s by design. “I don't put a lot of graduate-level information in it,” Pettine says. “We know in places like New England, it's only a matter of time that they somehow mysteriously end up with our playbook.”

Pettine told a story of how, at Wes Welker’s wedding, Tom Brady bragged a little bit to Jets outside linebackers coach Mike Smith, who was Welker’s college roommate, that the Patriots may or may not have had possession of a couple Jets defensive playbooks.

“It didn't shock me because Rex would give them out like candy anyway,” Pettine says. “He gave one out to [Alabama coach Nick] Saban and I was like, 'Don't you know Saban and Bill [Belichick] are pretty good friends? I have a feeling it's going to end up in New England.'”

I don't put a lot of graduate-level information in it,” Pettine says. “We know in places like New England, it's only a matter of time that they somehow mysteriously end up with our playbook.

When it comes to teaching the players the scheme, one of the tenets is the sponge theory, which Pettine learned from his father, Mike Pettine Sr., the retired legendary high school football coach at Central Bucks West in Pennsylvania.

“It's your job as a coach to keep throwing stuff at them and at some point, you'll get feedback,” Pettine says. “But you're going to have teams, like the 2006 Ravens defense, that had almost like an infinite sponge. We could have 60 calls up on game day, it doesn't matter. Those guys Ed [Reed], Ray [Lewis], Adalius [Thomas], Jarret Johnson—those guys could handle anything you threw at them. If your team's cumulative sponge isn't big, then you might have to back it off a little bit. I think sponge-wise, we're pretty smart. We already have some advanced stuff very quickly. But there's some coaches that each year, teach, This what we run and that's it. They don't ask more of their guys. To me that's coaching. If your guys can do more and you’re not doing more, that's on you. Or if this is your norm and you have a pretty good team and they're just not mentally there, then [expletive] pare it back a little bit.”

Pettine has also continued the learning buddy system that goes back to his days as a Ravens assistant. A smarter player will be paired with a player who is not learning the system as quickly. The smarter player will get the minus if his buddy screws up on the play.

“One of the rules we had was you never wanted to be limited by your least intelligent player,” Pettine says. “You have to do it that way because if you have a guy that can be elite but he can't be cluttered, like when we got Kris Jenkins in New York for a limited amount of time—when we had him, we didn't want him thinking. We would build it like, 'Hey, line up here and go, and we'll make it right around you.' We'll give the thinking to the guys around you. We've put some of the heavy-lifting thinking on a fewer number of players.”

Behind Pettine, the 2013 Bills defense ranked fourth in passings yards allowed and 10th overall. (Bill Wippert/AP)

Thomas was one of those guys in Baltimore. David Harris was the guy with the Jets. Safety Jim Leonhard traveled from the Ravens to the Jets to the Bills because nobody knew the scheme better than he did.

When it comes to teaching the players, it starts with giving each player an inventory of techniques specific to their position. For example, corners will learn how to play press coverage, man coverage with safety help, playing inside-outside with another player, squat coverage for Cover 2, and so forth. Each player has his own inventory so when he hears the defense being called, he only needs to know two things: how do I get lined up, and what’s my technique?

“Then you hope that the coaches have meshed together those 11 jobs so that you have a functional defense,” Pettine says. “Our big saying is, ‘Do your job, good things will happen.’ So we keep them very narrow-minded on, ‘Do your job first.’ A lot of mistakes are made when you're wanting to do somebody else’s job.”

When it comes to executing the defense on game day, this is where the real genius of the scheme comes into play, because it allows the unit to appear more multiple and confusing to the quarterback. The chaos, however, plays out as clarity in the minds of the defensive players.

The Browns teach the concept of the scheme. For example, with the dime defense, they don’t just tell a player, “This is the dime and this is your job every time we play it.” Initially, they will install the base system and the responsibilities. But then they’ll rotate jobs after a week. So the scheme is the same, but the personnel changes. If the Browns are in dime one week and linebacker Karlos Dansby is rushing in a certain gap, it might be a different player with that responsibility in the next game. That happens throughout that dime defense. Cornerbacks switch with linebackers, linebackers swap with linemen and corners become safeties. Chaos to a quarterback.

Forgotten NFL Dynasty

Long before Manziel Mania, the Cleveland Browns were the game’s dominant franchise, with a daring and innovative coach who pushed the NFL into the modern age. So how did it go so wrong? FULL STORY

“For our guy it's easy, and that's the business that we want to be in, something that's easy for us to do, that's hard for the other side to decipher,” Pettine says. “If you're a quarterback that figures out your protection by players, jersey numbers, and now you're trying to identify our stuff, now you're in trouble. We might run the same pressure three weeks in a row, and it's going to look different three times. We have a defensive back doing an end’s job; the next week it’s a different grouping with a linebacker doing it. So to somebody else it's going to look completely different, but for us it's the exact same call.”

When it comes to the season, the players aren’t just looking at a playbook with a position against that opponent. The playbook for each opponent has defensive players’ jersey numbers in it. They just look through the playbook for their number and know their assignment that week. And by switching roles, that allows the players to buy in.

“If I have a job that's crappy—late contain on the quarterback, that type of thing, I'm a little more likely to have a pretty good attitude doing it because I know next week I might have a job that could potentially be the free runner,” Pettine says of players’ mindsets. “Now they say, ‘OK, I'll do the dirty job this week, knowing that later I'll get the better job.’ ”

The final part of the puzzle is to have the entire defense in the meeting room together. It’s few and far between when positions break up, go to their own room and worry about themselves, like most teams operate.

“I thought that was one thing that Rex did real well. He kind of tied in the whole room,” Pettine says. “After a while, he'd ask a defensive lineman a question about the cornerback’s technique to see if the guy had been paying attention. It’d be funny to see how much guys would recall in situations like that. Learn the defense as a whole and you execute as one cohesive unit.”

* * *

Ultimately the Browns are going to have to play good football to compete in the AFC North. Pettine, who will likely be calling the defense, tapped Kyle Shanahan to direct the offense because of his track record winning games in different ways with different quarterbacks (running the ball with Texans and the read-option with Robert Griffin III in Washington). The Browns will feature a lot of fast motion offensively, and will be multiple with an improved running game because they’ll need to run it in Cleveland in December.

“I don't want to be ground-and-pound,” says Pettine, distancing himself a bit from Ryan’s mantra with the Jets. “People have already attributed that to us. But I don't. I want to score points. But I think you have to have the ability, especially here in Cleveland.”

The Browns will also run their offense with a variety of tempos, because Pettine knows firsthand that doing so gives defensive coordinators more trouble than always running up-tempo, like the Eagles and Bills.

Whether it's Brian Hoyer at quarterback or someone else, Pettine wants his offense to score points and be comfortable playing multiple tempos. (Diamond Images/Getty Images)

“I think you need to vary tempo, like New England does, which is smart,” Pettine says. “What I found going against our offense [during practice in Buffalo] is it just got rhythmic. I do have to call faster and have a sense of urgency, but then it's like anything else, you get into a rhythm. Play's over, call the play. Play's over, call the play. When your brain can think that way, it's very beneficial.

“It's tough when you have a certain tempo and then all of a sudden it goes 800 mph for a series. The whole rest of the game as a playcaller, I'm sitting there with one eye on the field, one eye on the call sheet thinking, Are they going to do it again? Then you end up rushing a few calls later in the game because there's the implied threat of up-tempo. I think that's something that smart teams do, something we're going to do here. We'll mix our tempos between going absolutely as fast as we can, code word, one-word calls everything (again, like New England), and we go. And then we'll practice all those tempos, and go as slow as possible as well.”

Offensively, the Browns will also devote much time in practice to two-minute situations, third down and red zone. “That's where you win and lose games,” Pettine says. “Anybody can go out and practice first and second down. Is it important? Sure it is, but not as important.”

Pettine will also be busy trying to nail down game management, which he thinks is the difference between 6-10 and 10-6. To that end, his desk is covered with books and teaching sheets from other coaches about time and game situations.

But the Browns will start their turnaround campaign with a shape-shifting defense that appears complicated to opponents but isn’t to the players executing it. The scheme and the innovative teaching methods have been battle-tested with the Ravens, Jets and Bills, and now they’re coming to Cleveland thanks to the accidental coach of the Browns. Still think of him as a meathead football guy, or a high school coach who has overachieved before his time? What you see with Mike Pettine isn’t what you get, just like his defense.