‘You couldn’t tell me winning a Super Bowl would feel any nicer’

I miss playing in the CFL, no doubt about it. Boy, it was a lot of fun. People in America have no clue what goes on up there, or about the quality of football we had. That’s what made the experience for me. Most of the guys were NFL-caliber talent, but were undersized or just didn’t fit the mold in one way or another.

My CFL career started in 1990, with the BC Lions, and I didn’t know what to expect. But I could tell I was going to be viewed as a backup in the NFL, and you only have so many years to play this game, and I wanted to play. So I figured I’d give the CFL a whirl. When I first went up to Canada, I thought I’d put in two years up there and then try to get back to the NFL. But I enjoyed it so much, I wound up making a career out of it.

The game in Canada was more exciting, more explosive, more wide open. It was what the NFL is now becoming. We were going no huddle, over the ball, from the time I got up there. No-back sets, six wide receivers, throwing the ball all over the field. There is a 20-second clock between plays rather than 40. It just creates a pace that the NFL is now realizing to be more exciting—and actually more effective. The NFL is turning into a no-huddle, up-tempo, fast-paced, throw-the-football type of game now. The CFL has been that for the past 30 years.

By the time I finished up in the CFL, I was basically my own offensive coordinator, calling all the plays on the field. We had our playbook, but I had my ideas from watching film during the week of game-planning and seeing things on the field. My whole theory at quarterback was to keep my receivers from having to think too much. Let them just be full speed and go. Rather than making them read everything on the fly and then adjusting, I would give them a route and they would just run it. I told them, “I’ll deal with the pressure, I’ll deal with the hot reads, I’ll build something in where I’ll get rid of the ball quickly.”

The NFL is turning into a no-huddle, up-tempo, fast-paced, throw-the-football type of game now. The CFL has been that for the past 30 years.

When I played in Toronto, we were playing a regular-season game against Edmonton, and I called a quarterback draw. The running back, Robert Drummond, was going to run a swing route to try to pull a linebacker with him. But the linebacker lined up on the edge, and it was an all-out blitz, so there was nothing in the middle of the field. It was either going to be a touchdown or we were going to be stopped at the line of scrimmage. Drummond was faster than I was, so just before the ball was snapped, in the middle of my cadence, I said, “Hey, just jump in and take the snap direct and run the draw.” He busted it for like a 70-yard touchdown.

Another time, we were going into the Grey Cup against Saskatchewan in 1997, and they had been giving us headaches with their zone blitzes. Instead of changing all of our pass protections and really worrying about it, I built in a hitch screen. Every time they came with a blitz from one side of the field, I would just turn and throw the hitch screen. They tried to zone blitz three or four times in the first quarter, and we averaged like 18 yards a catch off this silly little hitch screen to a back or wide receiver. And they quit doing it. We just lit them up. We scored a mess of points and had a really efficient day.

To do that in the NFL, though, it would probably have to be a coordinator’s idea. And then you would have to clear it with the offensive line coach, to make sure you can block all this stuff. Then you would have to execute it a couple of days in practice, and if it looked OK, it would make its way into the game plan. In the CFL, I was in a position where if I saw something in the middle of the game, I could just put it in without having to ask anybody. As long as you keep it simple enough, guys can just react and go. The NFL, for years, has been a copycat league. A coach would have to see something be successful elsewhere before he was willing to try it—and the league has been very slow to change because of that.

‘You couldn’t tell me winning a Super Bowl would feel any nicer’

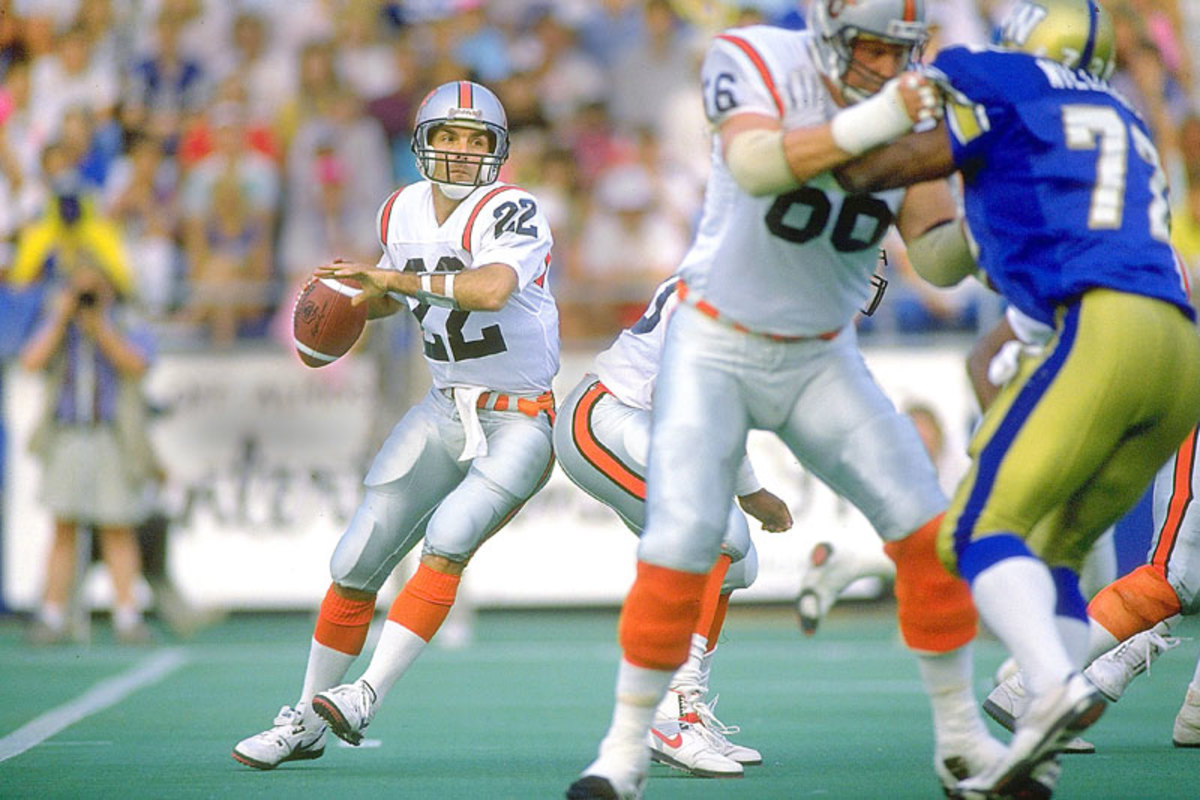

After brief stints in the NFL and the USFL, Flutie joined the CFL in 1990, playing two seasons for the British Colombia Lions. (John Biever/Sports Illustrated)

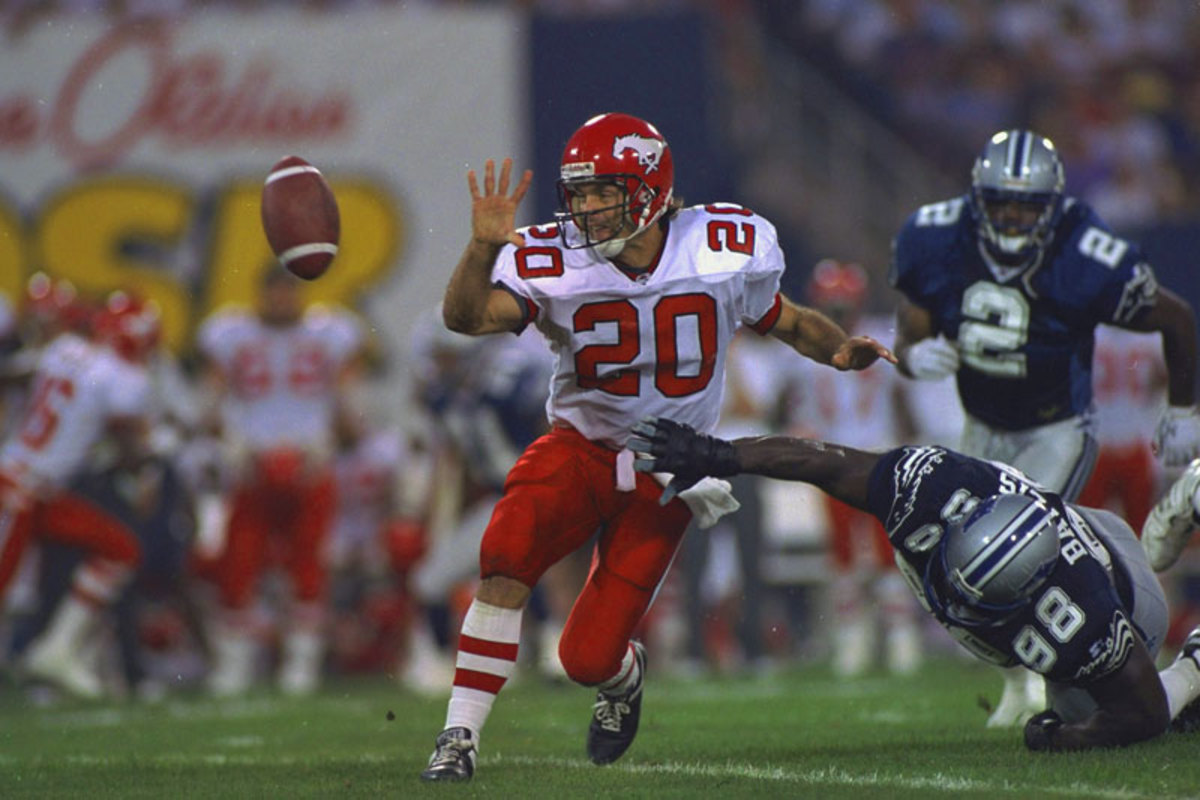

He quarterbacked the Calgary Stampeders to the Grey Cup in 1992. (John D. Hanlon/SI)

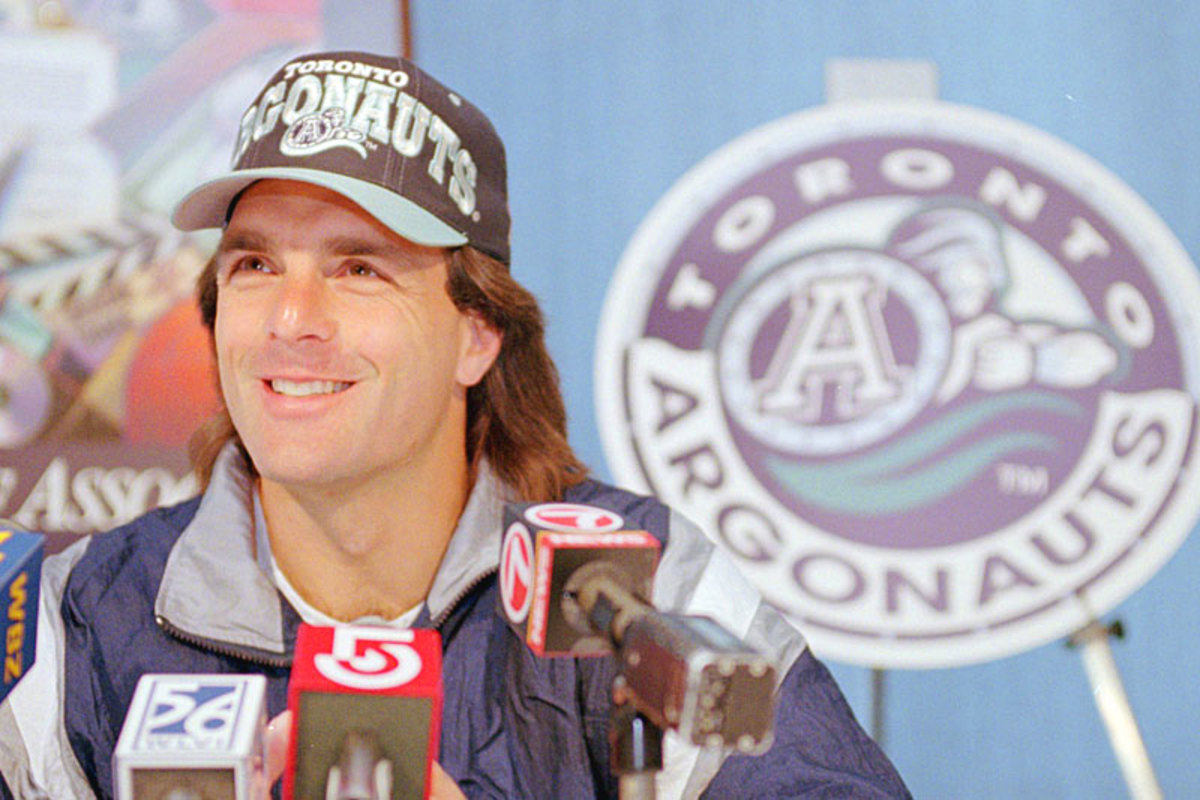

Flutie, the 1984 Heisman winner, answers questions at a press conference on May 10, 1996 after signing a $2.25 million contract to play for the Toronto Argonauts, whom he led to back-to-back Grey Cups. (Jim Rogash/AP)

Flutie (2) celebrating his second CFL championship—and his first with Toronto—on Nov. 24, 1996. (Anne Glassbourg/SI)

Flutie’s improvisational style of play and play-calling flourished in the up-tempo, no-huddle CFL. (Al Tielemans/SI)

Flutie returned to the NFL with the Bills in 1998, earning the league’s Comeback Player of the Year Award. (Damian Strohmeyer/SI)

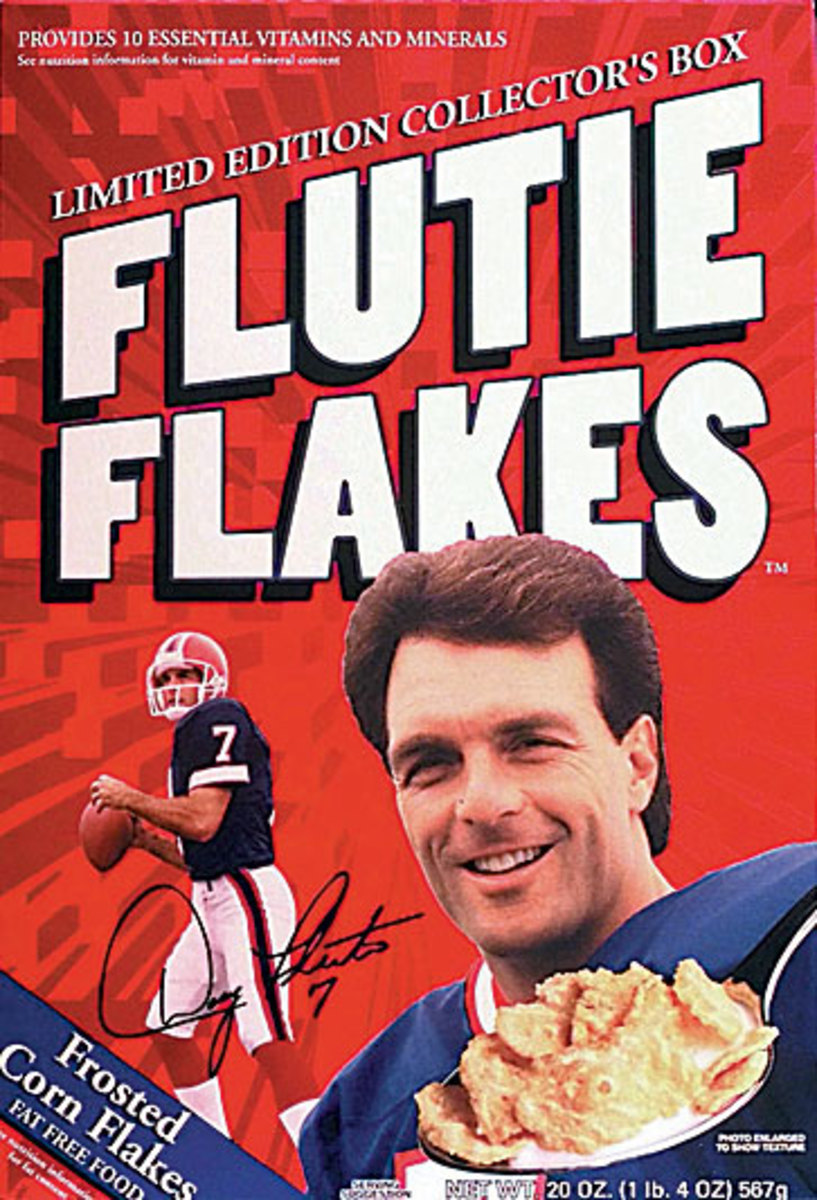

Flutie, who inspired a new take on a breakfast cereal, played until he was 43, going from Buffalo to San Diego to New England. (David Duprey/AP)

I’ll tell you what drove me nuts more than anything: I went from calling my own plays in the CFL, then back to the NFL for eight seasons, where I had a radio in my helmet and as soon as one play ended, the coaches were talking to you in the helmet for 20 seconds. It took so long to get a play call in, and your first thought was, What is the coach looking for? rather than, What do I want to do here?

During my days with the Buffalo Bills, we were a running, play-action team that played really good defense in low-scoring games. You adapt, and you do it that way. But boy, the mindset was different. When I was in the CFL, I was very aggressive. Aggressive in my play-calling; aggressive in my decision-making. In the NFL, I became much more passive, trying to do what I thought the coaches wanted me to do all the time.

Of course, when you’ve got a Peyton Manning, a Tom Brady or a Drew Brees—a guy who has been in an offense for a number of years—the trust factor goes up. The coaches start letting go of the reins and let quarterbacks have much more of a say. But I never got to that point with an NFL team, where I was there long enough (or starting long enough) to gain that trust. In the NFL, with what’s at stake money-wise and the pressure on coaches, they want total control because their necks are on the line.

In the CFL, it was more of a game. And it was a lot more fun. The length of the workday really helped with that, too. By CBA rule, they could only keep us there 4½ hours. In the NFL, it’s 10- to 12-hour days, every day, and it becomes a grind. I know the NFL is a big business, and it’s getting more complicated and tougher, but the burnout level, especially for quarterbacks, is crazy. I just wish there were some way around that, to somehow keep the fun in the game.

The MMQB is invading Canada. On Monday, Bears coach Marc Trestman wrote about his time north of the border and everything you need to know about the CFL’s rules and quirks.

I was actually, for a while, making more money in the CFL working a 4½ hour workday than I would have in the NFL with a 12-hour workday. And I was in total control of the offense. You can see why I enjoyed it so much. I’d go in around 10 a.m., watch some film on my own and do some game-planning, grab lunch, and then start the day with the team at 1 p.m. We’d end by 5:30.

I’m pretty sure the trajectory of my career would have been different today. I would have been in a position to be more successful in the NFL running some of these current styles of offenses, and I think an NFL team would have been more open to turning me into a franchise guy if things went well. I was always viewed by NFL teams as a band-aid: A guy who could help us win, keep us competitive, and while he’s doing that, we’re going to go find our franchise quarterback. It has turned into a little bit different mentality now with the success of guys like Brees and Russell Wilson, and the success of the spread offenses in the NFL.

But the CFL gave me so much. When I left Toronto for Buffalo, I was 35 and I was ready to retire. I figured I’d come back to the NFL for maybe a year or two, just to prove I could do it. I ended up playing another eight years. That was just crazy. The CFL gave me the opportunity to be a starter, regain my confidence, and then come back and be a starter in the NFL. And, I got to play eight games with my younger brother, Darren. We were both with the BC Lions in 1991.

Another thing I'll always remember is how fanatical the fans are up in Canada. Especially in some of the smaller markets, this is their football and they love their teams. You can draw a parallel with just about every city to a team in America. Saskatchewan reminds me a lot of Green Bay. They live for their team. Hamilton, with its blue-collar fans, is Pittsburgh. Calgary would be Denver—you’re at an altitude, and everybody who goes into Calgary to play is out of breath.

Calgary is where I won my first CFL championship, in 1992. We played against Edmonton in the Western final to go to the Grey Cup, and we had to drive the length of the field, into the wind, in the last seconds to win that game. I ended up running the ball in from a few yards out for the winning score. That was my shining moment that season.

Then we played the Grey Cup in Toronto, and I just remember dominating the game against Winnipeg. The last minute or two, I was standing on the sideline with Dave Sapunjis, my receiver and best friend on the team, putting on our Grey Cup champions hats, and playing to our crowd behind our bench. It was just a moment in time for me. You couldn’t tell me winning a Super Bowl would feel any nicer.