From the Akron Pros to the Seattle Seahawks: Race and the NFL

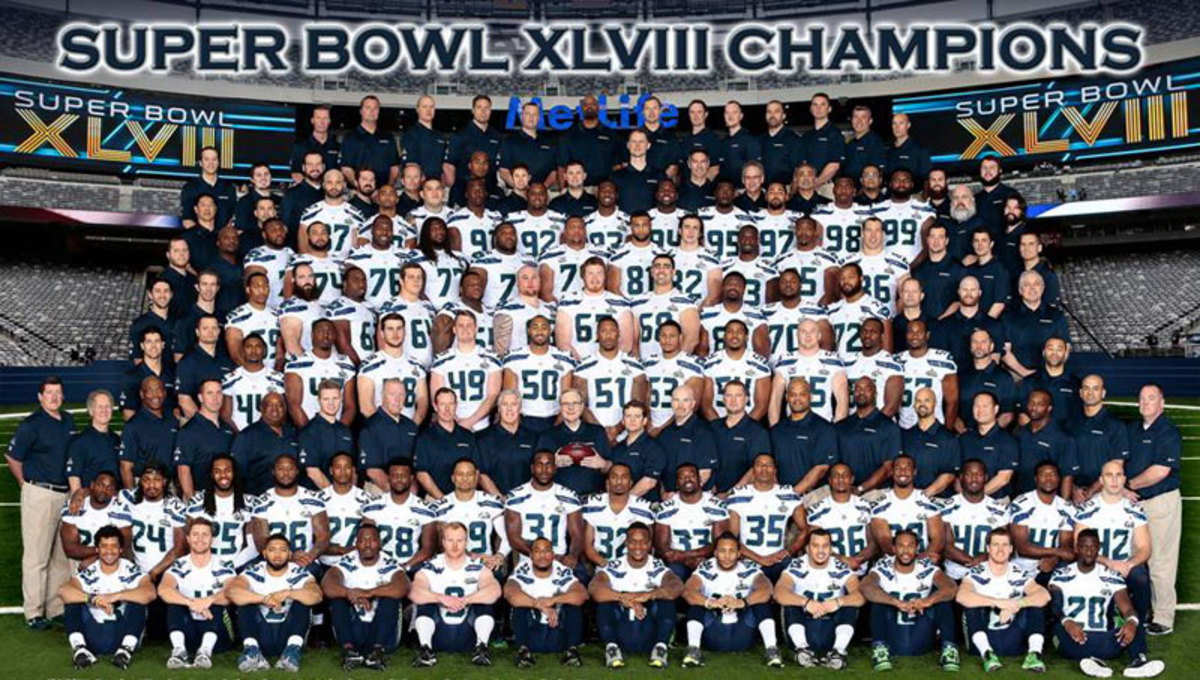

When the Super Bowl ended last February, after celebrating with my teammates on the field for a few minutes and seeing our owner, Paul Allen, hoist the Lombardi Trophy, it was time to do one big press conference and a lot more individual interviews at my locker in MetLife Stadium. I’m not certain how long I spoke to the press, but it was longer than an hour, easily. I got questions about what it felt like to beat Peyton Manning (I didn’t; our team did), about how dominant our offense and defense were, about specific plays in the game, about being just 25 and winning the Super Bowl … and about a hundred other things too.

But as I thought back afterward, there was one question I didn’t get:

What does it feel like to be the second African-American quarterback to win a Super Bowl?

The amazing thing was, I knew. I knew, after the game, the history of it. It matters because our world is changing—for the better. America’s hearts are changing, and the NFL is changing too. The NFL is moving forward.

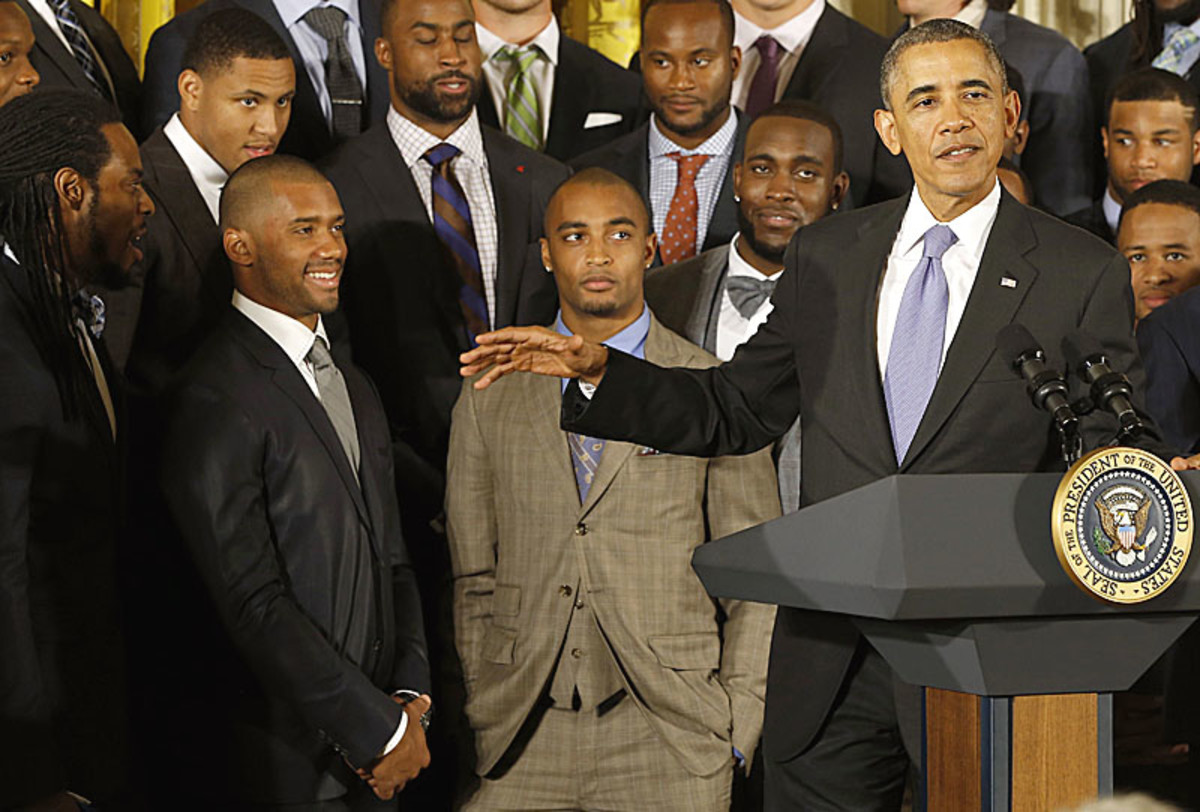

But it was interesting that no one talked about the black quarterback thing—at least to me—until our team visited the White House in May. President Obama said something about it that day: “Russell became only the second African-American quarterback ever to win a Super Bowl. And the best part about it is nobody commented on it, which tells you the progress that we’ve made, although we’ve got more progress to make.’’

President Obama was right on both counts. It’s a great story that probably is even greater because America isn’t talking about it. I knew that only one black quarterback, Doug Williams, had won a Super Bowl before our victory. I know history, and I know football history. I didn’t want to win the Super Bowl just because of the racial element, although I know that is significant. The Seattle Seahawks winning their first Super Bowl—that was the most important thing to me. Not me being such a young quarterback, or beating Peyton Manning, or not being the prototypical size for a quarterback. Nothing like that. I wanted to win because I wanted to win for my team.

I believe the culture has changed in America, and in the NFL. Nowhere can you see that more than in Seattle. I can tell you without reservation that Paul Allen and our GM, John Schneider, and our coach, Pete Carroll, don’t care what race you are, what color you are. They only care about performance. And yes, there is more progress to be made by minorities in the NFL, but I’m writing this story because I think that in the short time I’ve been in the league, I see a league and individual teams judging people for what they do, not what color they are or how tall they are or anything other than what happens on the field.

You know how I know that? From our practice field in Renton, Wash., throughout this spring.

The five quarterbacks in camp with us had something in common:

Me, African-American.

Tarvaris Jackson, African-American.

Terrelle Pryor, African-American.

B.J. Daniels, African-American.

Keith Price, African-American.

We call ourselves “The Jackson 5.” I play the role of Michael Jackson. It’s not that Coach Carroll and John Schneider purposely did that. They put the best guys they could find on the roster to help the Seahawks win. But really, considering the history of the league and the quarterback position, how crazy is it that one team has five quarterbacks in camp, and all are African-American?

I believe that says so much about the state of the NFL today.

A generation ago, could you have imagined an NFL roster with five black quarterbacks? We’re not the only one. The Jets could have three African-American quarterbacks on the roster on opening day. Buffalo and Minnesota, in the past two drafts, have spent first-round picks on African-American quarterbacks of the future. We had two NFC playoff games last year featuring African-American quarterbacks starting for each team—Carolina (Cam Newton) and San Francisco (Colin Kaepernick), and then San Francisco and Seattle for the conference championship.

But this is not all about black quarterbacks. It’s about the league progressing to being more of a place where it’s about ability first, second and third, and about the history of a league that has had some blind spots when it comes to race to be sure—but probably has been a little more progressive over the years than you think.

* * *

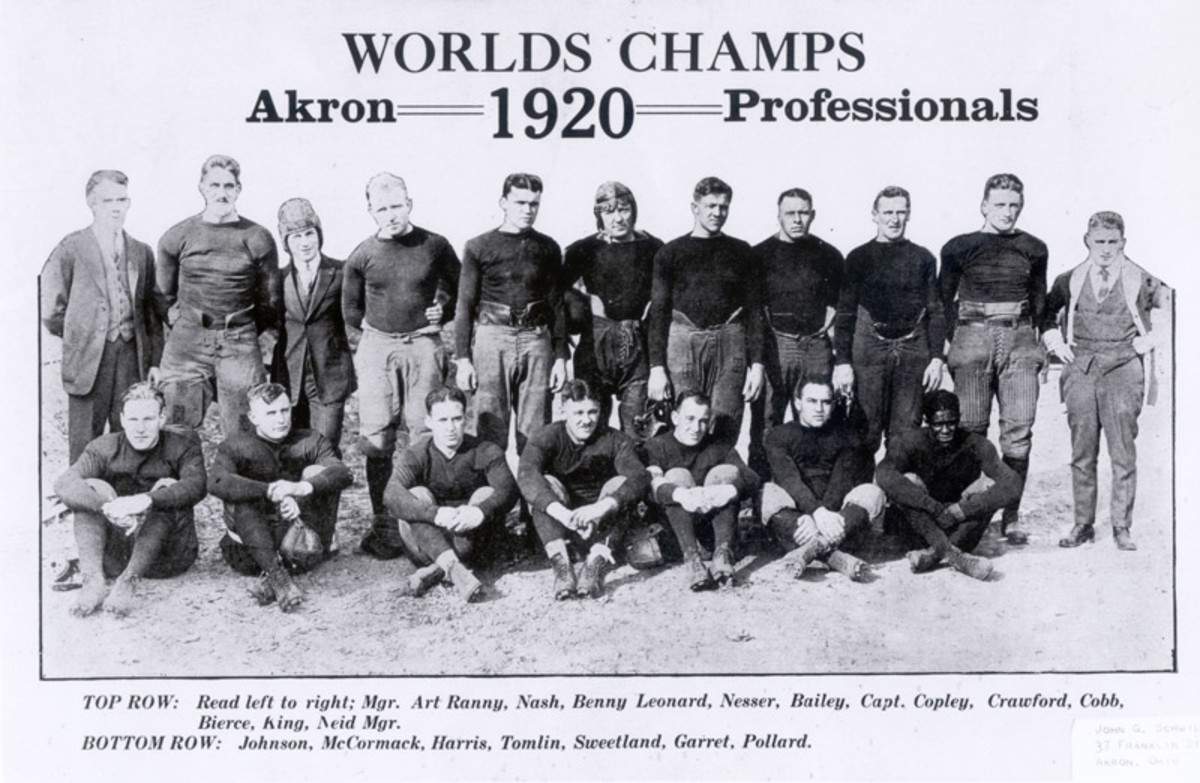

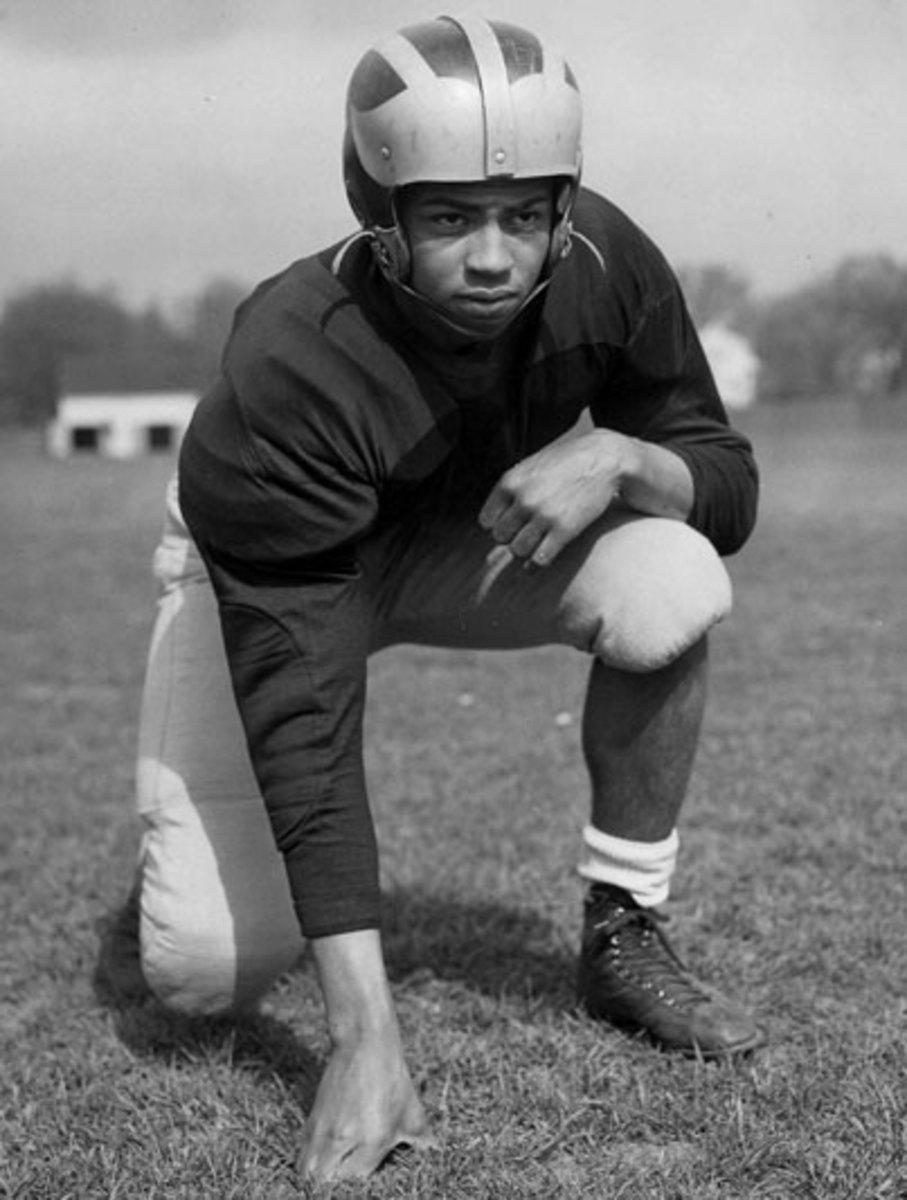

In 1920, the team photo of the first-place team in the league that would eventually become the NFL had a black face among the players: Fritz Pollard, who played for the Akron Pros. That’s 27 years before Jackie Robinson suited up for the Brooklyn Dodgers. It’s hard for me to go back in history, but that is astounding—an African-American player in pro football 94 years ago. The next year Pollard became the team’s player-coach. A year before Robinson played in Brooklyn, two more pro football teams—the Los Angeles Rams and the Cleveland Browns—signed African-American players.

From the Akron Pros to the Seattle Seahawks: Race and the NFL

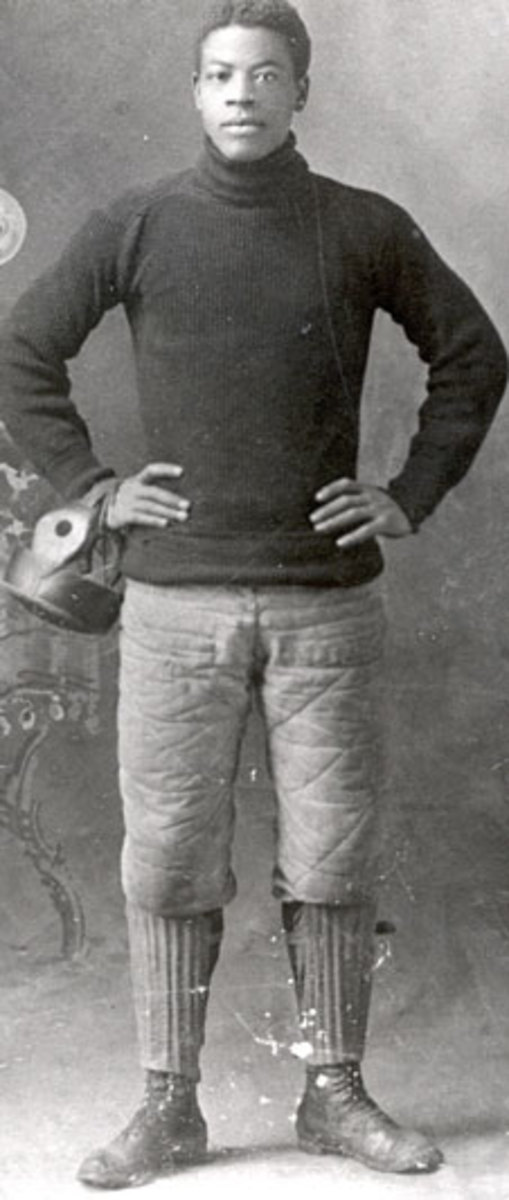

Nearly 100 years ago, and 27 years before Jackie Robinson broke baseball's color barrier, Fritz Pollard (seated, far right) was a key member of the Akron Pros. (Pro Football Hall of Fame)

The reigning champions. Russell Wilson is seated in front row, far left. (Rod Mar)

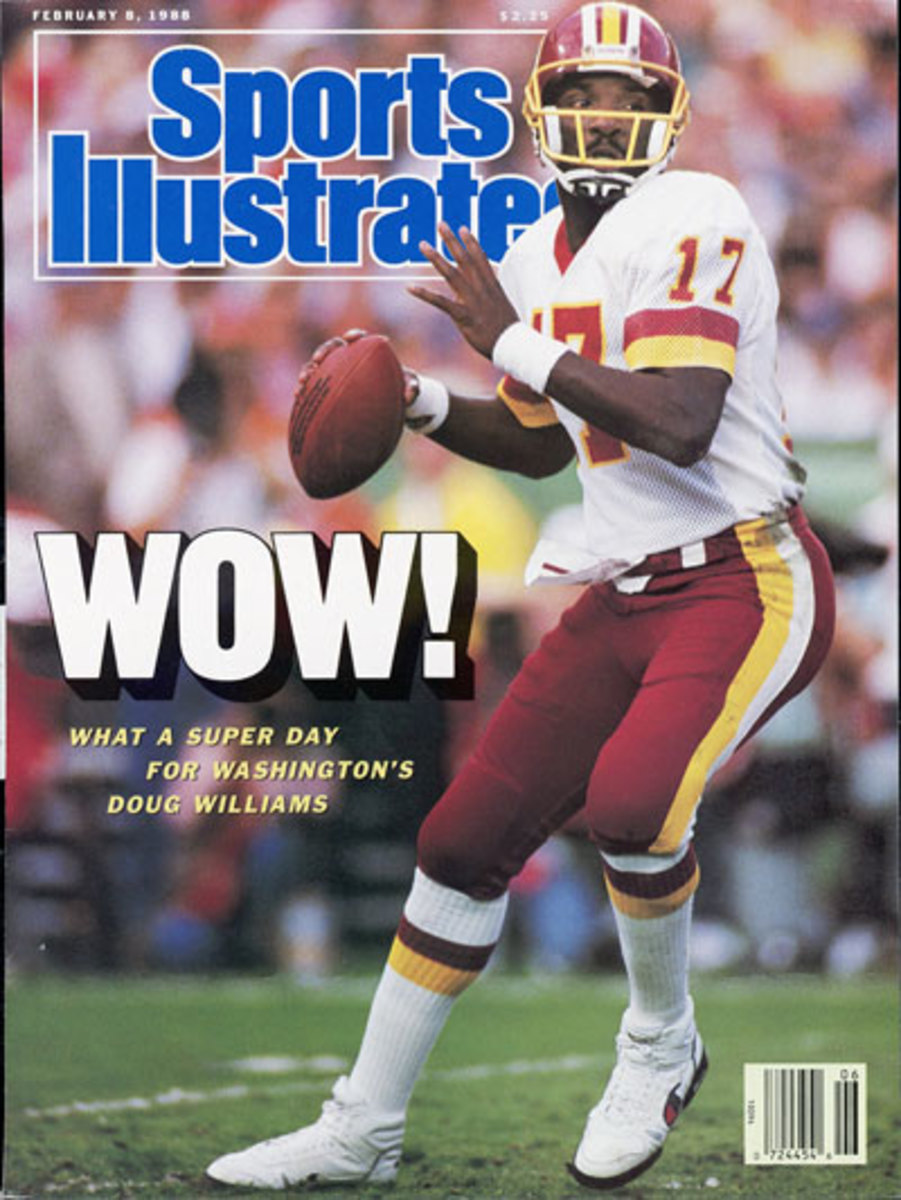

Since then it’s been a struggle at times, but we’ve seen the Rooney Rule make every team have to interview an African-American candidate when there’s a head-coach opening. We’ve seen teams like Pittsburgh, Oakland and Kansas City scout the predominantly black colleges to give some Hall of Fame players a shot at making it great. One of those players, Doug Williams from Grambling, turned out to be the first African-American quarterback to win a Super Bowl. That was 27 years ago, in Super Bowl XXII. What a trailblazer he was for all the minority quarterbacks who came after him: It’s the mark of a great player that he can have a great game in the biggest game of his life, and he threw four touchdown passes that day to beat Denver 42–10.

To get to where I’ve gotten, I’ve had so much help from standing on the shoulders of people like Doug Williams, James Harris, Randall Cunningham, Warren Moon, Donovan McNabb, Michael Vick and so many others.

But I also think in my case, my background and my family is so vital in getting to this point. That’s probably similar to a lot of players.

My family pushed me on the football field, on the baseball field, on every field. I had two very purpose-driven, faith-based parents, put on earth for a specific reason. They raised me to believe that it doesn’t matter where you come from; it matters where you’re going … and can you produce when you get there?

The MMQB’s special offseason series tracing pro football’s rise through the artifacts that shaped the game.

Week 7: The Arthroscope: The Little Tool That Saves Careers

Week 6: Television: Better Than the Real Thing

Week 5: Paul Brown and Cleveland’s Forgotten Dynasty

Week 4: The Day the NFL Died in L.A.

Week 3: Bill Walsh’s Enduring Genius

Week 2: Artifical Turf: Change From the Ground Up

Week 1: Steve Sabol’s Office: Where Legend Lives On

The word “color-blind” throws me off a little bit. My family definitely educated me about the world and what it was like out there. Education was always crucial to our family. My grandfather was a military guy who was an educated man and went on to be the president of Norfolk State University for 22 years. My grandmother was a professor at Old Dominion University. My grandmother, who was from Jackson, Miss., used to have to read old and outdated textbooks at school. At night she would bring home the more updated textbooks from the white schools and study those—then bring them back to their places in the morning. That’s how my mom and dad grew up, with the idea that education was the most valuable thing you could have.

But “color-blind’’ is not the right term. I certainly realized people’s color. My parents told me, “Don’t judge people based on their color. God created everybody.” I wasn’t naïve. I was educated on being African-American. I knew everything about Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King. I grew up in Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy. You realized it was … a little bit different. The way I was raised, though, was about treating people the right way. Yes sir, no sir, work your tail off. It didn’t matter if I was black, white, Latino—and when some people meet me they think I’m Latino.

When I was really young, I knew this was something I wanted to do, and hopefully somebody would give me a shot. But I didn’t stress about it. God put me on earth to be the best person and best player I could be, and I was raised to understand that if I had the ability, I would get a shot. I have had people say derogatory things to me. I heard degrading words on the road in college, in both baseball and football. Most of it came from the opposing fans. But it was nothing that any other player didn't hear. Did I let it get to me? No. Others before me—civil rights leaders, other quarterbacks—fought for my right to do what I am doing, and they had to take far more abuse than I did. I am grateful for them.

Today, I don’t look at myself as a black guy, or a black quarterback. I look at myself as a person, and a quarterback. My attitude is if I want to be the best, I’ve got to beat the best. And it has nothing to do with color.

Milestones in the History of Race in the NFL

From the Akron Pros to the Seattle Seahawks: Race and the NFL

1904: Some 20 years before the birth of what would become the NFL, a 25-year-old from Cloverdale, Va., nicknamed “The Black Cyclone” is the first African American to play football professionally. As a halfback for the Shelby Athletic Club in Ohio, Charles Follis endures regular cheap shots from opponents, and the same taunts he’d endured playing for the Wooster College baseball team. In college he’d crossed paths with Branch Rickey, who played for a rival school and went on to sign Jackie Robinson. Follis’ career would end in 1906 because of injury, and he died in 1910 of pneumonia, his place in football history obscured for half a century. (Pro Football Hall of Fame)

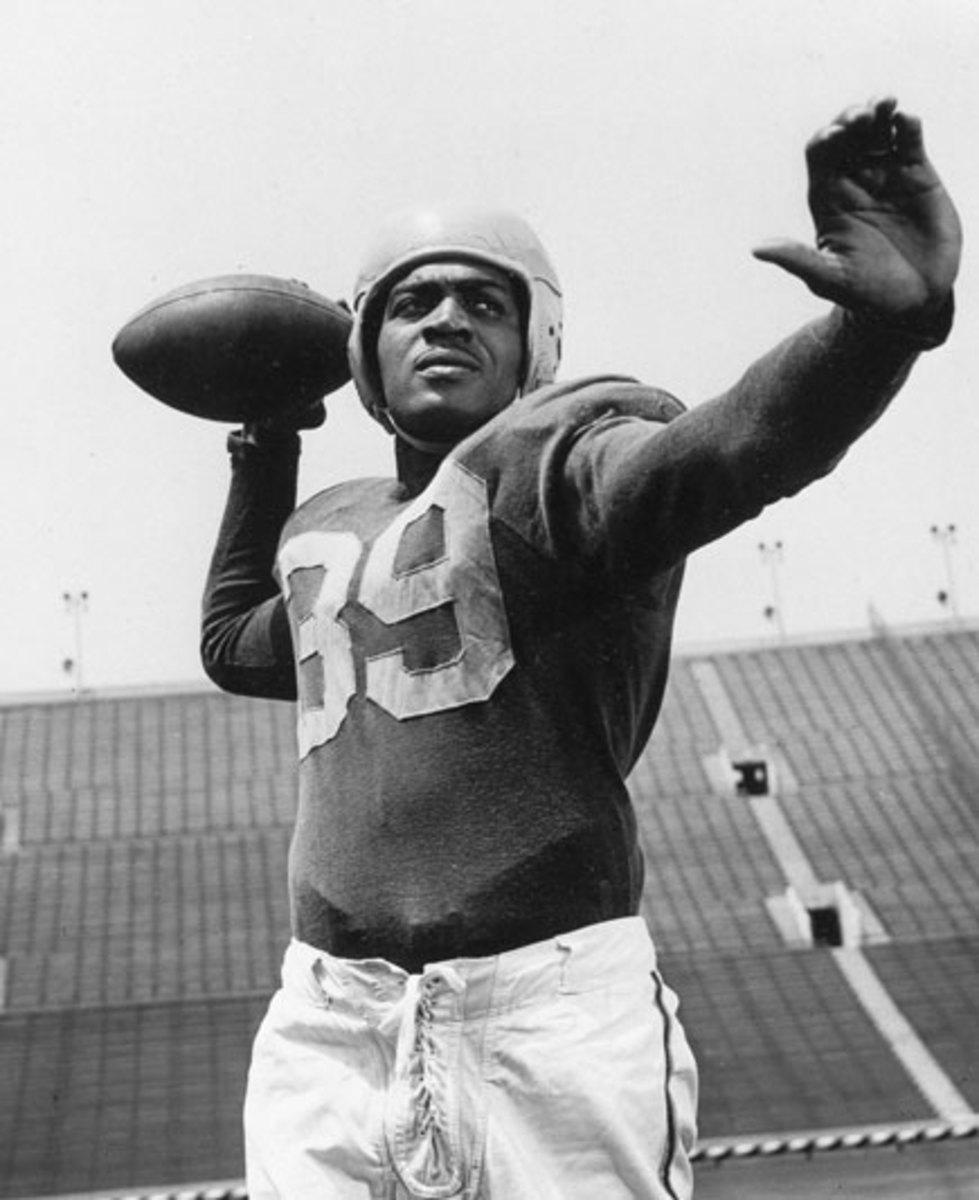

1921: One of two African Americans to play in the first year of the American Professional Football Association in 1920, Fritz Pollard (far left) one year later becomes the first black head coach in the league, now called the NFL, when the Akron Pros promote him to player-coach. The 165-pound Pollard served in WWI after starring at Brown, then led the Pros to the league’s first title with an undefeated season (8-0-3). Almost 100 years later the modern watchdog organization that oversees the NFL’s efforts to ensure hiring diversity bears Pollard’s name. (Pro Football Hall of Fame/AP)

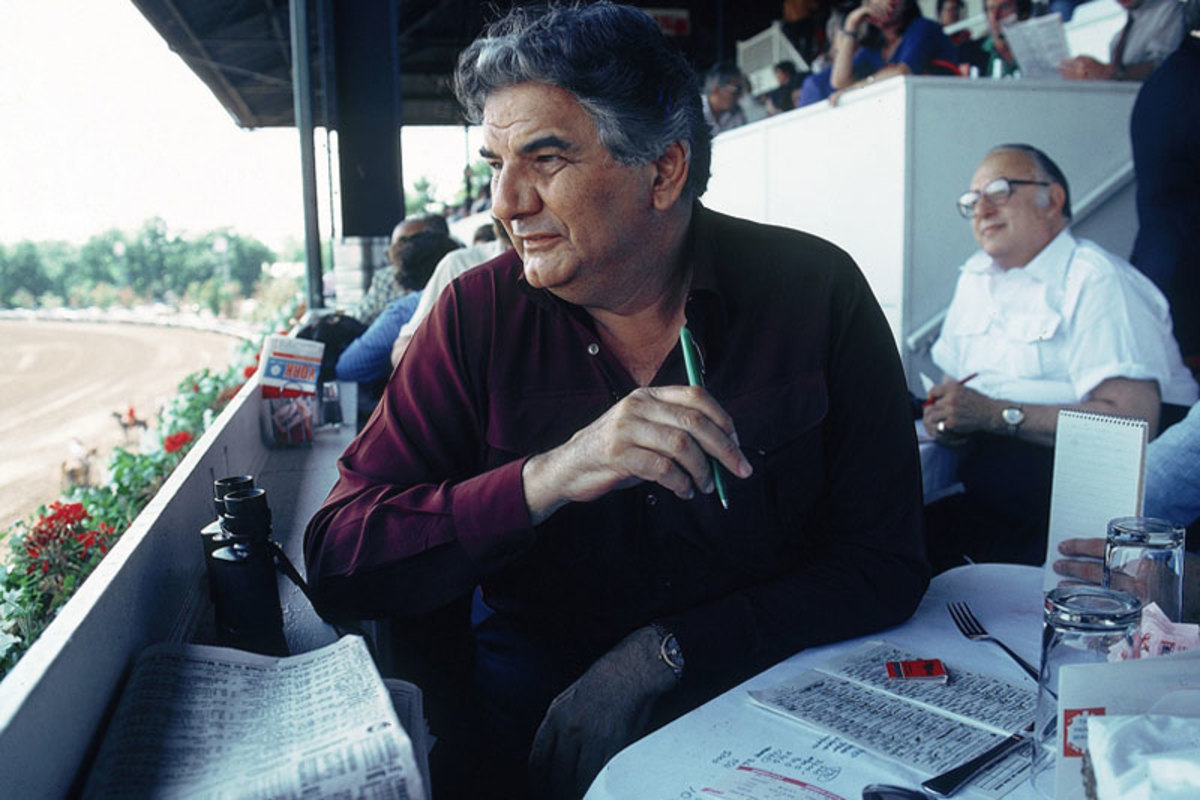

1933: Following the lead of Washington owner George Preston Marshall, NFL teams impose de facto racial segregation. Marshall (above) wielded significant influence after bringing success to the league by suggesting division realignment and a championship game, and when he moved his Boston franchise to the segregated city of Washington he insisted his team represented the South and “Old Dixie.” The few African Americans in the league were not brought back, and the NFL would be all-white until after World War II. (AP)

1946: The color barrier is broken for good when the Rams, newly arrived in Los Angeles from Cleveland, sign Kenny Washington, six years after Bears coach George Halas had lobbied owners to no avail to let him sign the UCLA standout. Joining Washington (above) on that ’46 Rams team is end and future Hollywood star Woody Strode. That same year the Cleveland Browns of the AAFC sign future Hall of Famers Marion Motley and Bill Willis, and the Montreal Alouettes sign Herb Trawick, the first black man to officially play in the CFL. (AP)

1948: The New York Giants continue to chip away at the color barrier by signing undrafted free agent Emlen Tunnell, who will play 11 seasons for New York. In 1959, Packers first-year head coach Vince Lombardi would trade for the safety nicknamed “offense on defense.” Tunnell, who would become the first black Hall of Famer, is told he has doubled Green Bay’s black population; the other black man in town shines shoes at the Hotel Northland. Tunnell’s response, unearthed by the New York Times decades later: “Well, I’ll live there, then.” (AP)

August, 1957: Art Rooney (center) takes a stand. When the Steelers travel to Jacksonville for an exhibition against the Bears, Pittsburgh’s black players are told they must stay at a segregated hotel and are barred from participating in a welcome parade. Steelers owner Rooney flies in from Pittsburgh and tells the black players, “I promise you, this will never happen to one of my teams again.” A year later, when the Steelers couldn’t secure accommodations for their black players before a planned exhibition in Atlanta, Rooney would cancel the game. (AP)

1962: To George Marshall’s chagrin, Washington is the last team to integrate pro football with the drafting of Syracuse running back Ernie Davis first overall. So upset is Marshall with the commissioner’s insistence upon integration, he orders coach Bill McPeak to make the selection in his place. Davis is traded before suiting up in Washington, but the team yields to pressure from the Kennedy Administration and signs five black players for 1962. Future Hall of Famer Bobby Mitchell (49, above) is among the group that endures numerous indecencies, including Marshall’s tradition of playing “Dixie” before games. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

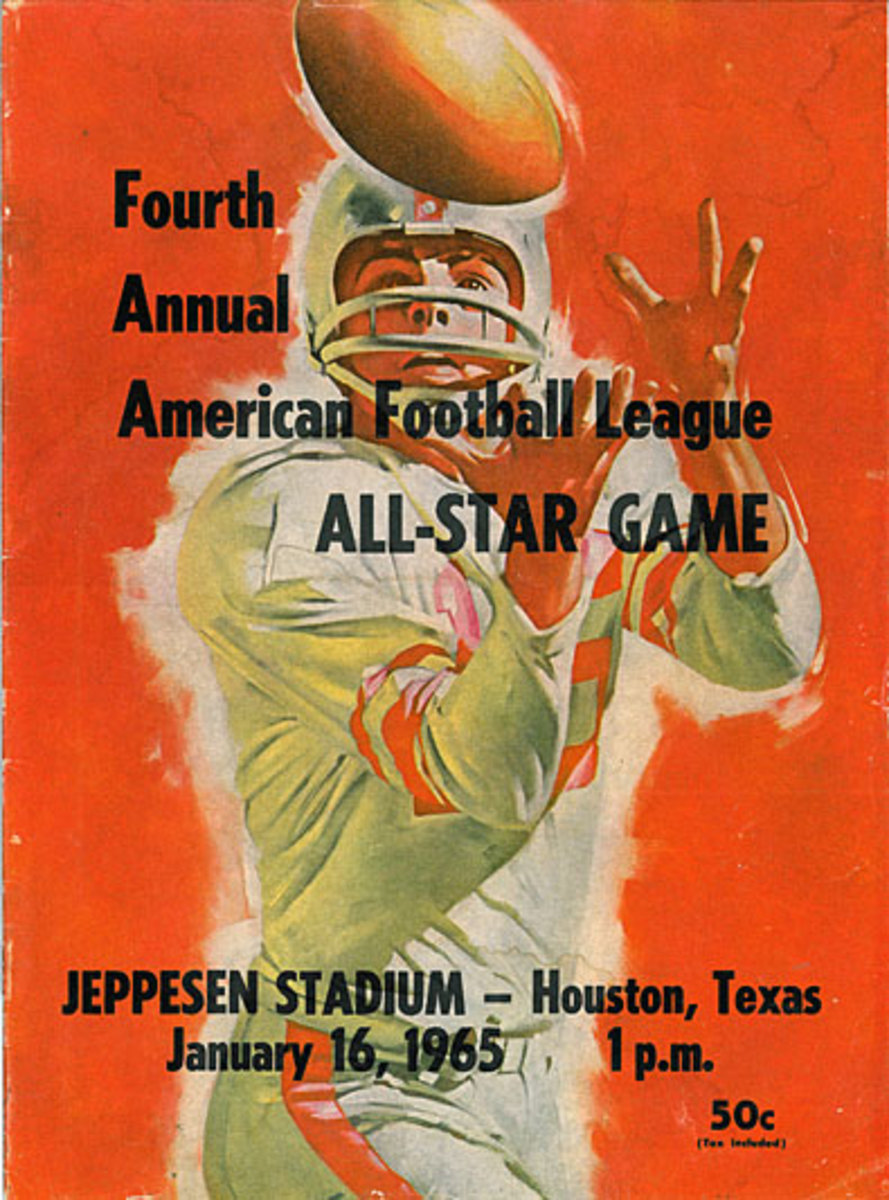

1965: Players stage a boycott of the AFL All-Star Game over segregated conditions in host city New Orleans, prompting the league to move the game to Houston. Upon arrival in New Orleans, black players are refused rides from the airport, denied service at restaurants and harassed in the streets. The 21 African Americans on the East and West rosters ultimately walk out, and they are joined in the boycott by white players including Chargers tackle Ron Mix. AFL commissioner Joe Foss ultimately announces the game will be relocated to Houston. (Pro Football Hall of Fame)

1965: The NFL hires Burl Toler as its first black game official. Toler would work 25 years in the league as field judge and head linesman and become the first black official in a Super Bowl when the Steelers beat the Rams 31-19 in 1980. Toler, who died in 2009, was a member of the 1951 University of San Francisco Dons team that went 9-0 yet were denied a bowl bid because of its two black players, Toler and Ollie Matson. Toler’s appointment in 1965 helped pave the way for Mike Carey to become the first African American to referee a Super Bowl, in 2008. (AP)

1966: Lowell Perry becomes the first African American to broadcast an NFL game to a national audience after CBS hires the former Steeler as a color commentator. Lowell was an eighth-round draft pick of the Steelers in ’53 but saw his career end that season due to injury. The team would bring him back as an assistant coach, then a scout, with Art Rooney backing Perry’s admission to Duquesne Law School. He would move on to pursue broadcast, law and business interests, and in 1975 President Ford would appoint him head of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (AP/Detroit Free Press/Eck Stanger)

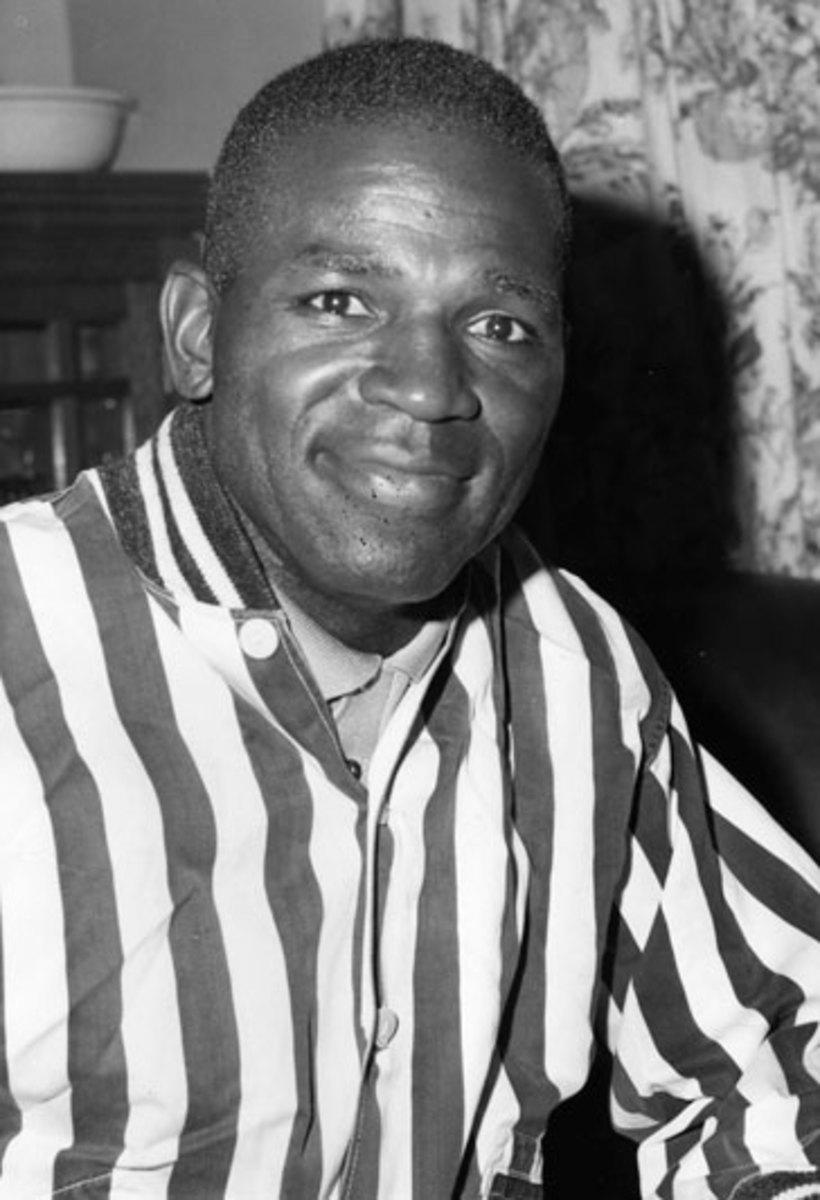

1966: The Chiefs hire sports photographer Lloyd Wells as a scout with a unique objective: mine historically black colleges, an untapped resource until then, for pro talent. On Wells’ recommendation, Kansas City drafted Morgan State middle linebacker Willie Lanier (above) 50th overall, pitting him against 47th overall pick Jim Lynch out of Notre Dame in a training camp competition. Lanier won the job, eight subsequent All-Pro nods and a Hall of Fame induction. The following year the Steelers would hire sportswriter Bill Nunn as a scout to similarly scout historically black schools, a key in building Pittsburgh’s ’70s dynasty. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

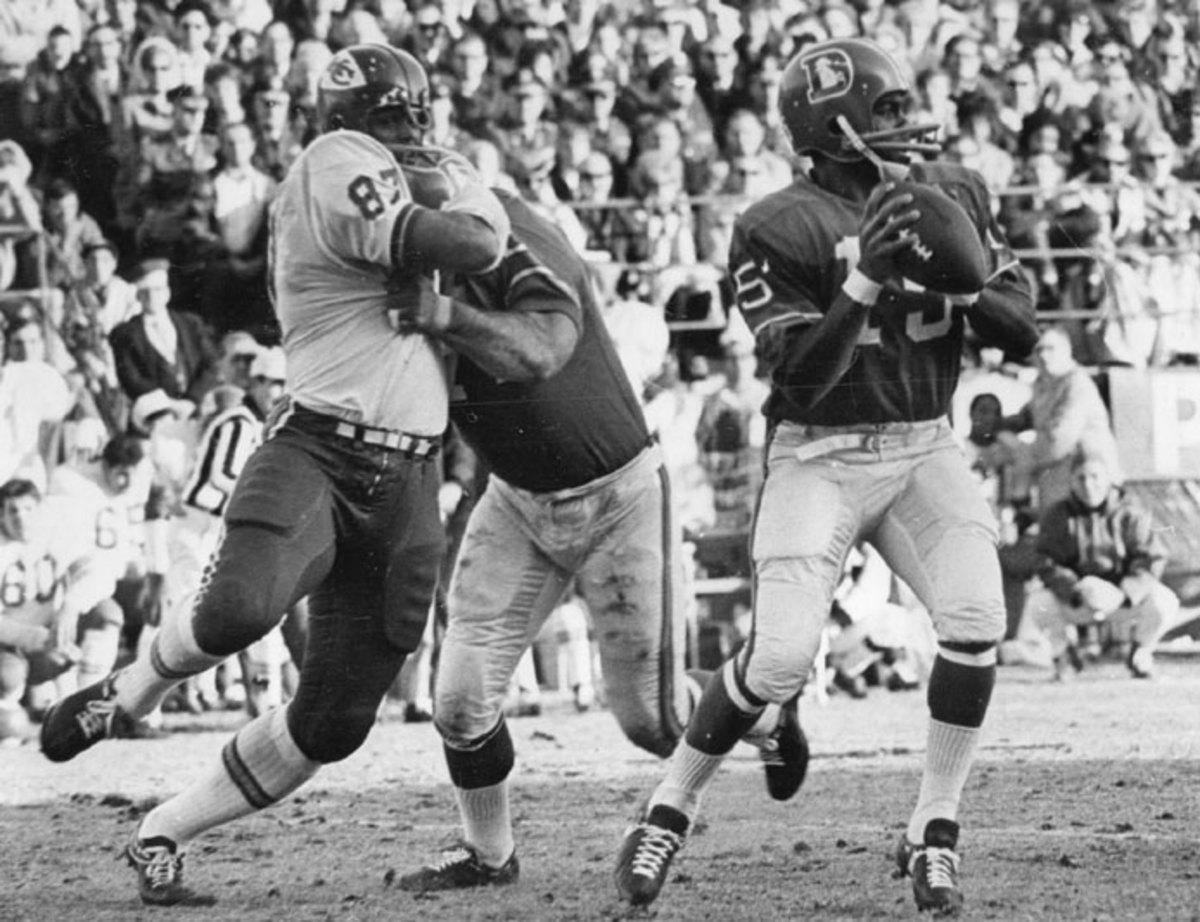

1968: Injuries compel Broncos coach Lou Saban to insert rookie Marlin Briscoe at QB against the Patriots, and Briscoe subsequently becomes the first black starting quarterback in the modern game. He would throw 14 touchdown passes that year, but as Saban had no plans to bring him back as the starter for ’69, Briscoe would leave the team and switch to wide receiver for the remainder of his career. (Bill Johnson/Denver Post/Getty Images)

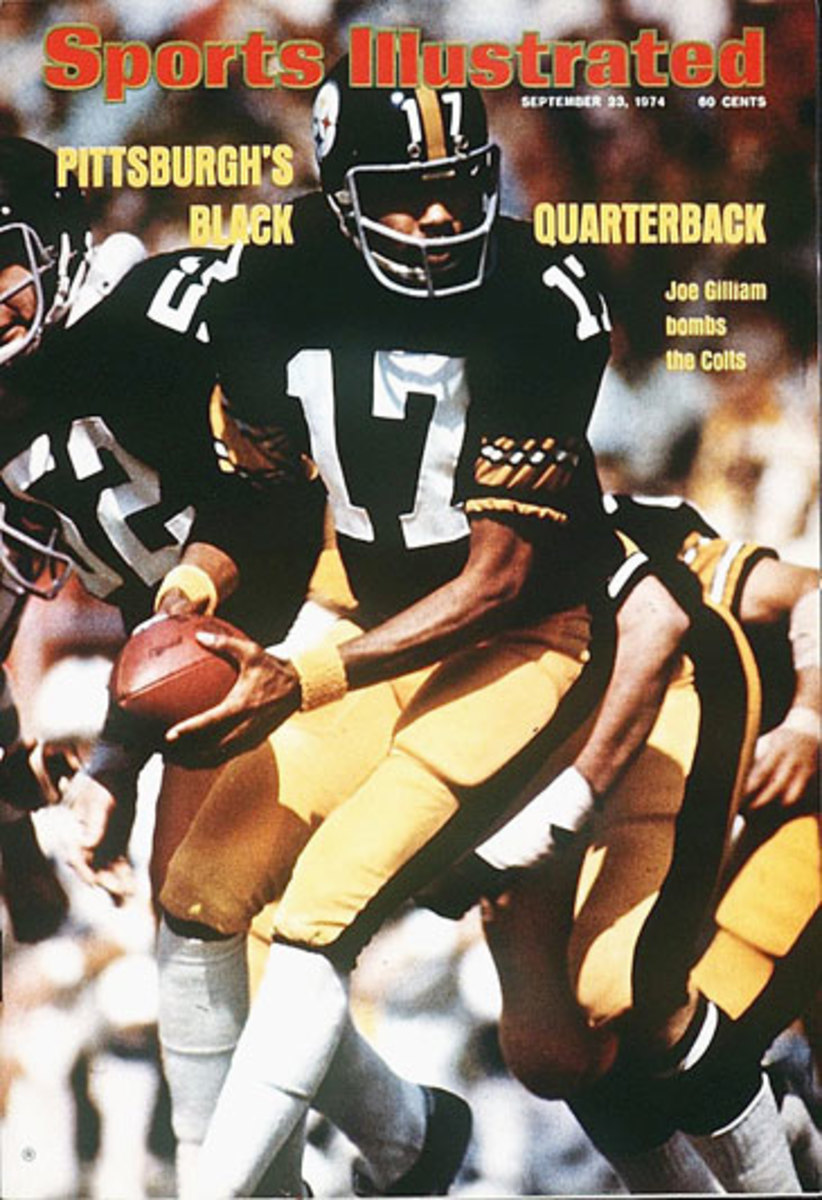

1974: Joe Gilliam temporarily supplants Terry Bradshaw as the Steelers’ starter and makes SI’s cover under the billing “Pittsburgh’s Black Quarterback.” (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

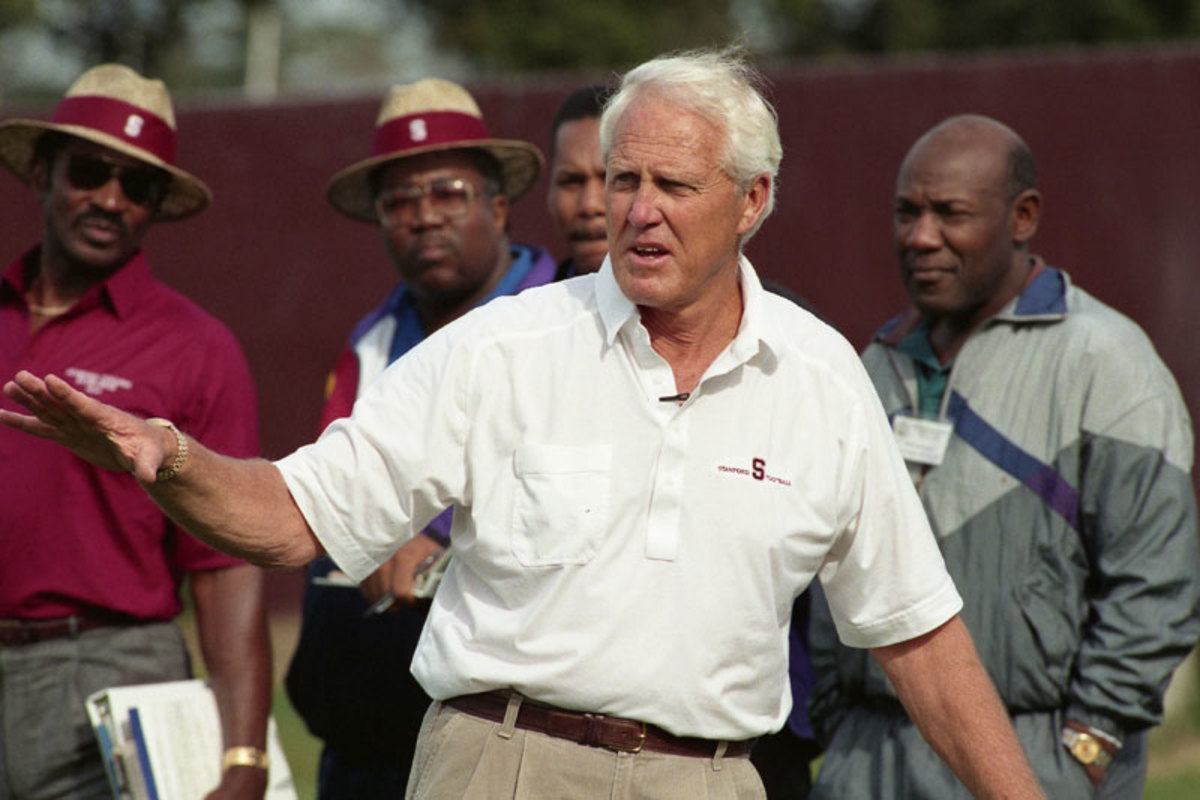

1987: Bill Walsh invites a small group of minority coaches to participate in 49ers training camp, spawning a league-wide program that has since given opportunities to nearly 2,000 coaching candidates. In 2012, the NFL established the Bill Walsh NFL Minority Coaching Fellowship Advisory Council, a 13-member panel of team presidents, general managers and coaches tasked with strengthening a program that boasts current head coaches Lovie Smith, Marvin Lewis and Mike Tomlin as graduates. (David Gonzales/Icon SMI)

January 1988: CBS fires oddsmaker Jimmy "the Greek" Snyder, a fixture of “The NFL Today,” for racially insensitive remarks made in an interview on the occasion of Martin Luther King’s birthday. Explaining the superiority of black athletes, Snyder remarked, "The slave owner would breed his big black to his big woman so that he could have a big black kid, you see." The backlash incites political pressure on the NFL to integrate its head-coaching ranks, and during Super Bowl week later that January, commissioner Pete Rozelle blames the NFL’s “good ol’ boy network” for the absence of a black head coach. (Lane Stewart/Sports Illustrated)

Jan. 29, 1988: Doug Williams doesn’t disappoint as the first black quarterback to start in a Super Bowl, leading Washington to a 42-10 win over John Elway and the Denver Broncos in Super Bowl XXII. Williams passes for 340 yards and four touchdowns in his second and final season as a starter in Washington. Sixteen years later, Seattle’s Russell Wilson would become just the second black passer to win an NFL championship. (John Biever/Sports Illustrated)

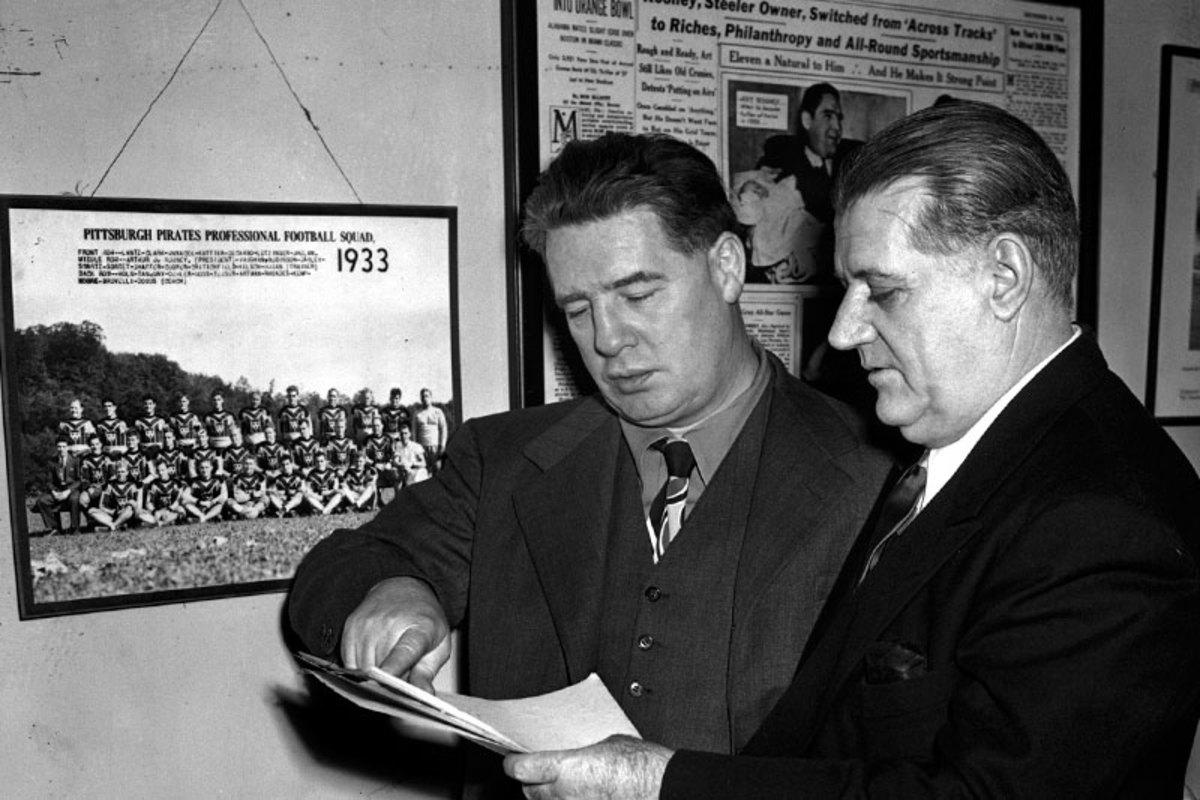

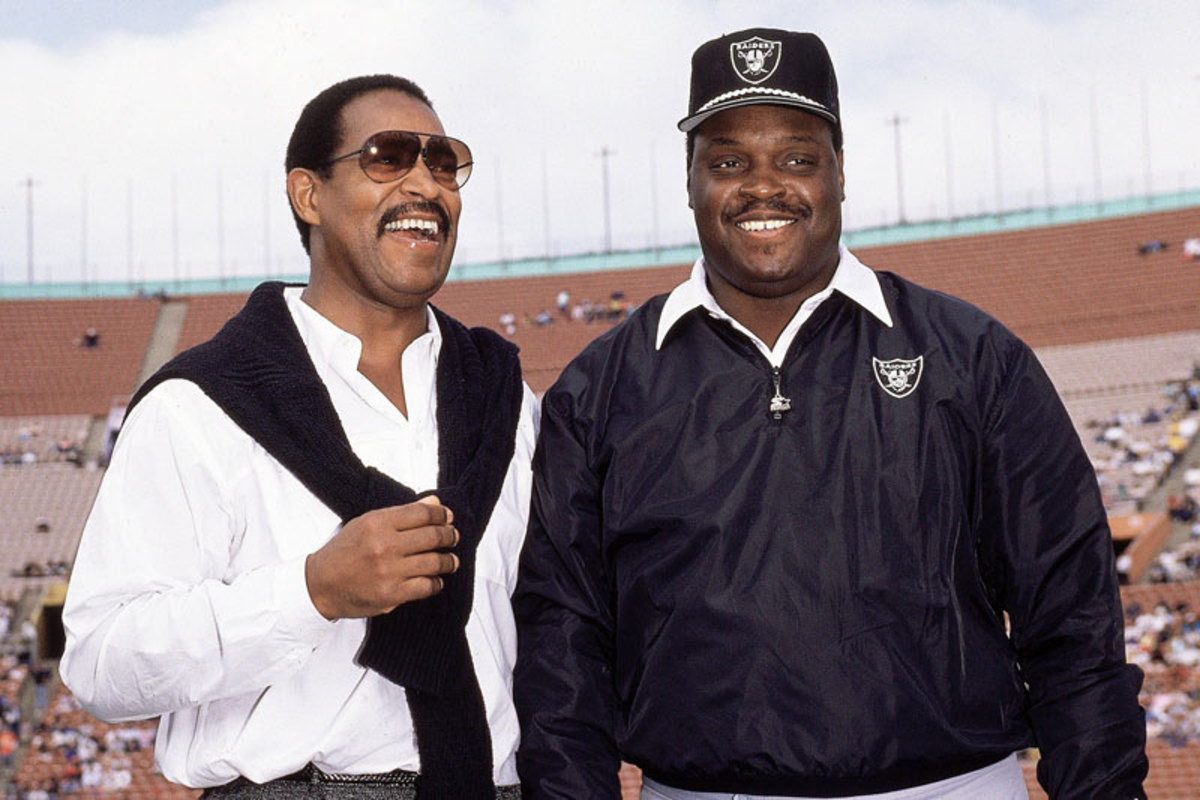

October 1989: Former Raiders offensive lineman Art Shell (right, with Gene Upshaw) becomes the first African-American head coach in the NFL’s modern era, setting off a string of minority hires over the next two decades. Raiders owner Al Davis promotes Shell from offensive line coach to replace Mike Shanahan midseason after a 1-3 start, commemorating the occasion in typical Davis fashion: “If this is an historic occasion,'' Davis says, “It will really only be meaningful and historic if he is a great success.“ Shell would last five seasons, earning an AFC Championship berth in 1990 before being fired after a 9-7 season in 1994. (Peter Read Miller/Sports Illustrated)

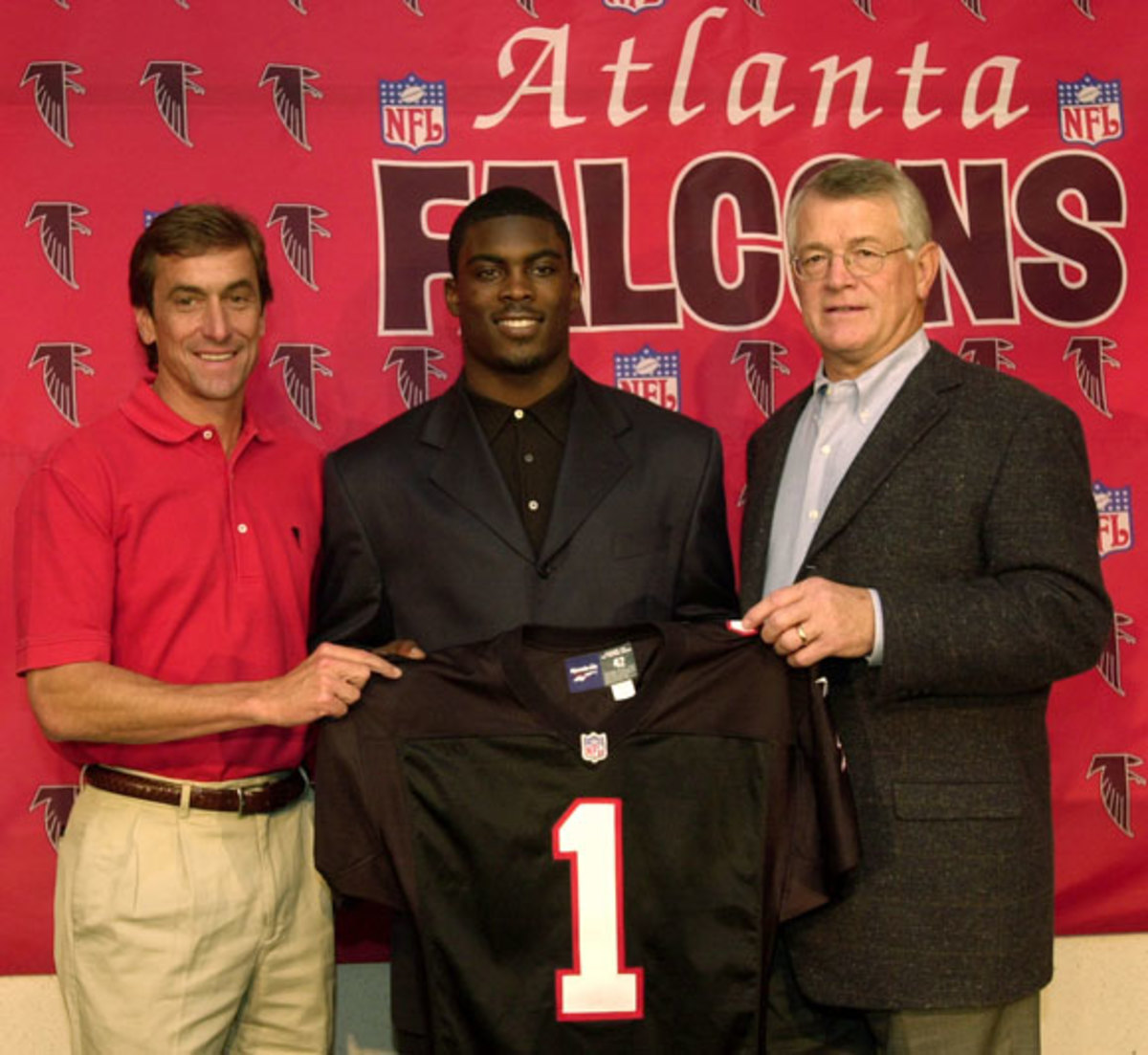

2001: The Falcons make Michael Vick the first African American quarterback to be drafted No. 1 overall. Over the next decade, Vick’s breathless escapability and cannon arm inspire a generation of young quarterbacks, and his illicit off-field interests eventually destroy potential that once seemed limitless. Two more black quarterbacks have since gone No. 1, Oakland’s JaMarcus Russell in 2007 and Carolina’s Cam Newton in 2011. (Gregory Smith/AP)

2002: Hall of Famer Ozzie Newsome is named general manager of the Baltimore Ravens. He’d been in a personnel role with the Browns since 1991, and in 1996, the team’s first since moving to Baltimore, he selected future Hall of Famers Jonathan Ogden and Ray Lewis in the first round, famously overruling owner Art Modell and coach Ted Marchibroda, who preferred troubled running back Lawrence Phillips to Ogden. Newsome has built two Super Bowl champions in Baltimore. (John Biever/Sports Illustrated)

2003: NFL owners vote unanimously to adopt the Rooney Rule, requiring teams to interview at least one minority candidate for head coaching and senior football operation jobs. Championed by former Browns lineman John Wooten (above) and named for the Rooney family and its legacy of hiring African Americans in leadership roles, the rule is often celebrated in offseasons when black head coaches are hired, and derided when they aren’t. Calls to strengthen or reform the rule intensified after the 2012 offseason, during which eight head coaching vacancies went to white candidates. Today, five NFL head coaches are black or Latino. (David Richard/AP)

2007: Two African American head coaches meet in the Super Bowl for the first time, with Tony Dungy’s Colts defeating Lovie Smith’s Bears 29-17 in Super Bowl XLI. Wooten, chair of the Fritz Pollard Alliance, calls the occasion not a milestone, but a meteorite. “I can‘t put into words what that actually meant,” he says. “It was the height of what we had been working for.” (David Duprey/AP)

When I joined the Seahawks, I remember walking into the huddle and seeing all the different faces. Here I am, 23, an African-American, a strong Christian. Our center, Max Unger, is from Hawaii. Our running back, Marshawn Lynch, is African-American, from the inner city in Oakland. Zach Miller, the tight end, is a white guy from Phoenix. I don’t care if they’re white, black, Christian, Jewish, atheist. It has no effect how I view them. They’re there for me, I’m there for them. All I want to know is: Are they great teammates? I think we’re all fortunate to have been picked by a team that’s shown over and over that only one thing matters: performance.

I’ll never forget Coach Carroll’s words the day I was drafted. We talked right after the pick. He told me that he believed in me and wanted me to come into camp and compete for the job. He promised me that that if I competed at the highest level I would have a chance to start.

These were his exact words: “I will play the best players. If you're the best quarterback, you will start.”

Isn’t that really what every football player wants to hear from his coach?

* * *

When I got to meet the President in May we talked for about 15 minutes, about leadership, about performance, about being able to affect people’s lives. It was pretty cool—not only meeting the President, but having him notice me trying to have an impact on people.

During the Seahawks' White House visit, President Obama pointed out what no one else had brought up in February: An African-American quarterback had won the Super Bowl. (Geoff Burke/USA TODAY Sports)

Obviously, he’s a very intelligent man. He’s not naïve about some of the barriers. Nor am I. But what is cool is that people don’t think of him now as the “African-American President” as they think of him as “the President.” At least that’s how I see it. I think that’s important for this country, whatever your politics are.

As I stood behind the President at the White House that day, I listened to his amazing speech about the Super Bowl and our team, and it dawned on me how special this moment really was. I realized then and there how the world is changing. I feel blessed to be a small part of that change.

I’m a quarterback. It’s not about color anymore. This off-season, I’ve worked as hard as I can to become a better player. I have to. I know what the situation is with coach Carroll: He’s going to play the best guy. But I wouldn’t have it any other way. The culture is going in the right direction, and the league is going in the right direction. The best player plays. So there is no time to sleep.

Week 8 Artifacts

The Super Bowl Shuffle The brash Bears released a ridiculous rap song and video during the 1985 season, then made up for it by storming, rather than shuffling, their way to a Super Bowl title. read more → |

|---|

Drew Rosenhaus’s Cell Phone For the man who embodied the new breed of super agent, the mobile phone became the primary tool in a billion-dollar business. read more → |

Don Shula’s 1972 Game Plans How do you plan out perfection? Shula’s offensive and defensive schemes for the ’72 Dolphins led to the league’s only unbeaten and untied season. read more → |

Frank Reich’s 1993 Wild-Card Hand-Warmer Jim Kelly’s backup mostly cooled his heels on the sideline during Buffalo’s Super Bowl years, but when called on he had the hot hand in the NFL’s greatest comeback. read more → |

Jimmy Johnson’s Super Spray His predecessor famously covered his bald pate in a fedora, but Johnson sported a magnificent, if immobile, coif as he led the Cowboys back to prominence in the ’90s. read more → |

Pete Rozelle’s 1989 Retirement Memos The man who guided the game to the heights of prosperity and success over three decades bid farewell in the simplest of ways. read more → |

NFL Draft Clock It’s down to the crunch time when a team is “on the clock”—decisions made in that brief period before a draft pick is made determine the fates of franchises. read more → |

Red Grange’s Barnstorming Tour Pro football was foundering before the Galloping Ghost left Illinois to join the Bears and bring the NFL to hundreds of thousands of fans. read more → |

The Wells Report A thorough investigation into the “bullying” of Dolphins lineman Jonathan Martin exposed the worst of the NFL’s locker-room culture and prompted calls for change. read more → |

Adam Vinatieri’s Tuck Rule Shoes The New England-Oakland playoff has gone down in history for a questionable call that prompted a rules change, but the Pats kicker was the real star in the snow. read more → |

Thelma Elkjer’s Vase Sometimes momentous decisions—like how the newly merged NFL and AFL will align itselt—come down to a simple solution. read more → |