So This is the NFL, Part II

AURORA, Ohio — The players are exhausted on all fronts. Some are even annoyed.

This has been the message for as long as there’s been a rookie symposium in the NFL: Odds are, you won’t make it in this league.

It’s Day 3 of the league’s annual orientation in Aurora, Ohio, and Niners VP of Football Affairs Keena Turner can see the mental fatigue setting in: “Players get tired of hearing that the average career only lasts three years, but it’s like my kids; I can’t just tell them something once and expect them to get it.”

Says former player J.R. Tolver, a Tuesday panel speaker, “You hear that three-year thing and you say, That's them, not me. After a while they keep saying it and you're like, Next.”

From the time they arrived Sunday, one rookie estimates he’s heard the three-year stat no less than 30 times. There’s good reason: These four days are up against, in some cases, a lifetime of poor mentorship and the impending summer of idle hands and fat checkbooks.

DAY 3

So This is the NFL, Part I

Second-year stars talk groupies, Eddie George talks life after football, and Donte Stallworth talks about avoiding the tragic mistake he made. Check out Robert Klemko's account of the Rookie Symposium's first two days. FULL STORY

Money is a constant theme here, whether it’s the earning, saving, investing or spending. In a morning session on media relations, Tucker tells the rookies a normal 30-second radio commercial costs $5,000, but players get interviewed on the radio for free. They ought to take advantage of the free marketing. NFL Vice President of Football Communications Michael Signora joins Tucker onstage, unintentionally alternating pronunciations of “media” when reading off a teleprompter and not.

“Remember that you’re talking to fans,” says the Long Island native, “not the medi-er.”

After the morning session the rookies pile onto buses for their first trip away from the Bertram compound. Traditionally, the third day of the symposium is spent at an NFL Play 60 event hosted by the Browns at their Berea practice facility. Reminded by observant NFL staffers to flip their backwards and upside down visors to the proper position, the rookies join about 100 elementary school kids on the practice field for a series of improvised football drills hosted individually by each team. The results were fantastic.

You know those Play 60 commercials with exuberant kids and grinning football players running around in slow motion as if they’ve never been happier? It was like that, but in real life… for two hours. Chris Borland, the 49ers’ fourth-round linebacker, dazzles a group with a tumbling routine including three backflips. Vikings rookies take turns placing playful jams on mini-receivers. Washington rookies bash children with orange handheld pads, looking sheepishly back at NFL chaperones for approval as the kids tumble to their bellies.

Cardinals quarterback Logan Thomas and the rest of the NFC rookies had the chance to play around at a Play 60 seminar. (Tony Dejak/AP)

Some 20 reporters wait for Michael Sam to submit to an interview, one of few since his coming out prior to the 2014 NFL draft. Yet none of the assembled scribes work up the nerve to ask a question overtly related to his sexuality, much less mention the word “gay.”

Local media swarm Teddy Bridgewater, who is asked to defend comments that he’d told his agent Cleveland was not where he wanted to go on draft night.

When the interviews are done and the children have had enough, a BBQ awaits at the end of the field. The kids have a chance to sit and admire players up close, but halfway through lunch the long-posturing clouds open up and the party’s over.

By 2:30 p.m., the rookies are back in the big room. Dr. John York, co-owner of the 49ers, is talking about the NFL’s expansive efforts to track injuries and make the game safer. It’s the first time in 17 years they’ve had an owner at the symposium. To the chagrin of several organizers, a restless rookie shouts “What’s up Doc!” when York takes the stage.

A lack of couth is nothing new at the symposium. Many on the production crew have been working the audio and visual components of the event since 1998. They can recall, from nearly each symposium, the players they thought would suffer in the NFL based on behavior here. Sean Taylor, who was fined for leaving the 2004 symposium, was an obvious choice. When he wasn’t skipping sessions, Pacman Jones actually turned his back to the speakers and slept for some of the symposium.

At the 1998 symposium in Denver, Ryan Leaf stretched out across three chairs and slept, then left. Meanwhile, a few seats away Peyton Manning filled his notebook. Guess which one is a Super Bowl champion and which one currently sits in a Montana prison.

There are sleepers in 2014, too. One observer counted three snoozers during the 8 a.m. media session. And while a rules session with Dean Blandino brings excitement over highlight-reel hits, a dozen questions and some dry wit from the NFL’s officiating boss, there are more sleepers by the time Tolver, Ryan Mundy, Jordan Palmer and Deion Branch step up for a panel on life after football.

Tolver, whose wife and young daughter listen in the green room, describes how he turned earnings from six pro football seasons into a successful Panamanian commercial recycling business. Branch describes his experience shadowing a homicide detective in Albany, Ga., in 2004—and the subsequent realization that he never wanted to be a homicide detective.

All talk about the importance of networking, with Palmer clarifying: “The bottle service guy is not part of your network.”

Not surprisingly, Michael Sam was a popular man during media availability during Tuesday's outing. (Tony Dejak/AP)

As the panel wraps up, the league’s breakout facilitators prepare their conference rooms for the second-to-last session of the symposium. Donovin Darius, an NFL safety for 10 seasons who was hired by the league a year ago, lights a Yankee candle and plays A Tribe Called Quest’s mellow classic “Check The Rhime.”

The lights are on when the Rams and Buccaneers rookies arrive in a room with about 15 chairs arranged in a semicircle facing inward. There’s no sleeping here. The conversations in the private setting are engaging and informative. Panel speakers occasionally drop in to answer questions, but this is about the players figuring it out for themselves.

“I just facilitate,” Darius says. “As they come out of here they’re going to have a game plan for success, not because I gave it to them, but because they learned and listened.”

Taped up on the walls of the room are seven large pieces of paper with categories of challenges the rookies will face: Family, Friends, Financial, Character, Relationship, Rookie Year and that all-important Next Month. By the end of the session, the pages will be filled with specific challenges, solutions and resources.

Near the end of his second symposium, Darius rattles off the most consistent concerns of players:

How do you deal with females understanding that you’re now a target?

How do you deal with the entitlement of family members who now see you for what you can give them?

Who can I trust to support my interests in the NFL?

Everyone is TMZ,” Carter tells them. “Even the ones in your crew,” adds Sapp.

“This generation is much more aware than we were,” says Darius. “They’re more confident than we were, because of technology and everything available to them. The danger is too much information. You can get paralysis by analysis.”

Dinner is Bubba Q’s boneless ribs, a revelation to the SEC rookie contingent. Bubba (former NFL defensive end Al Baker) has developed a way to remove the bone from the rack of ribs without damaging the integrity of the meat, an innovation that landed him on the reality show Shark Tank and propelled his Avon, Ohio-based business into a regional power.

But Bubba is just an appetizer for the symposium’s main course. Hall of Famers Cris Carter and Warren Sapp have agreed, for a small fee, to lead the last panel discussion. They are introduced on the big screens with a video montage; each of them watches from the green room. There’s a clip from early in Sapp’s career, a Bucs-Vikings game with the pair going head-to-head. In it, Carter sidles up to a corn-rowed Sapp after a play and says, "Big fella, I'm gonna give a you a little bit more time to use what God gave you. You a leader. God wanna’ use you. You ain't get all that talent for yourself!"

Watching the clip from a green room couch, Sapp bursts into laughter and falls to his side as if he’s been shot.

The longtime friends take the stage as the rookies applaud. Carter, wearing black and white dress shoes, lays his Hall of Fame jacket across the back of his chair. Sapp wears a polo and jeans, sans jacket. They spend about 30 seconds in the chairs before advancing to the edge of the stage. Before they were legends, both stumbled on and off the field. Tonight, they deliver a message of practicality.

“Do not believe them when they tell you [your team] is a family,” Sapp says. “When you go to Disney World with your family and the baby is falling behind, everybody stops for the baby. That’s what a family does. But this is a brotherhood of men. You’re going to have to be accountable to the men that you line up with.”

Sapp’s delivery is understated. He clenches a fist, pounding it into an open hand with a fatherly look on his face. Carter is animated, pacing and shouting with the cadence of a Southern Baptist preacher. He brings up Rams rookie Lamarcus Joyner, whom Carter mentored in high school, and invites him to try on his Hall of Fame jacket to the oohs of the crowd.

“If somebody told you right now, at the end, you could be in the Hall of Fame,” Carter says, “what would you do? Because you need to answer that question in five weeks. If somebody had told me what that jacket would mean, I wouldn’t have gotten in trouble. I wouldn’t have been suspended. I would be a better teammate. I wouldn’t have been doing that dumb s--- if somebody had told me what this jacket would mean.”

Their advice is visceral and blunt.

Carter: “There's no hiding crimes anymore. Everybody is TMZ.”

Sapp: “Even the ones in your crew.”

Carter: “Say that again, bro.”

Sapp: “Even the ones in your crew.”

Carter and Sapp’s formula of braggadocio as motivation works well with this audience. They talk about their jackets and their rings, how their mothers are permanently retired, how Carter has never made less than $250,000 a year since ’87. Sapp once had “as many cars as the garage would hold.”

“These grown men in the league,” Carter warns, “aren’t trying to give that up.”

Carter (left) and Sapp were seated when their talk started. They didn't stay seated for long. (Courtesy of the NFL)

They start the Q&A right away, and Redskins rookie Lache Seastrunk asks a question that riles up the speakers: “What made you push every day?”

Says Sapp, “Boy, do you know they’re out there striking over $10 an hour?”

Carter: “What more motivation do you need? I want you to imagine being at Cowboys Stadium, back at home, and they say starting at running back: YOU. Back at home? Imagine how you’d feel! That’s the way you need to feel every morning. Because you’re blessed to even wear that logo, to even have your butt here… There’s only a few of us who’ve ever did this.”

Michael Sam asks for advice in conquering training camp, and Sapp delights in the opportunity to provide confidence.

“I watched your tape all day long,” Sapp says. “You know how to rip. I’ve seen you rip to the sky. Trust me, it still works. Go in with the same thing every day, and get a little bit better.”

Panthers first-rounder Kelvin Benjamin asks about dealing with family demands, and Carter takes the opportunity to call him out. He brings Benjamin on stage and attempts to slip the jacket on, but the 6-5 Benjamin is too long to get the second arm in. Carter drapes it over his shoulders instead.

“I’m gonna tell you,” Carter says, “you’ve got rare ability. You need to love the game, like when you were a boy. I didn’t always see that at Florida State. You might love your mama, but you don’t love football like I love it.”

Vikings rookie quarterback Teddy Bridgewater asks the best question of the day: “For many of us, football was the only way out. Do you have any advice on transitioning out of the game?”

Carter’s advice seems to contradict that of previous panelists.

“This is the best job you’re ever going to have,” he says. “I don’t like to get too much into your second career, because this is the hardest career you’re ever going to have. They can bring in somebody else to talk to you about your [next] career.”

They go on for an hour and a half, at times speaking to individual players as if they are the only ones in the room, at times screaming at the top of their lungs. They finish to a standing ovation. This is as honest and energetic as the symposium gets.

Carter sums it up, stomping and wild-eyed: “Do what the next man won’t.”

Green Bay Packers first-round pick Ha Ha Clinton-Dix snaps a picture of Deacon Jones' Hall of Fame bust. (Phil Long/AP)

DAY 4

The final day is Hall of Fame day. The rookies clear out of the Bertram at 7 a.m. and load onto five charter buses headed down the Ohio turnpike for Canton. A marching band from McKinley High greets them at the entrance, playing a rendition of Waka Flocka Flame’s “O Let’s Do It” that delights Lions tight end Eric Ebron.

The 10th pick of the draft is the most visible rookie at the NFC symposium, with an auburn-frosted mohawk fade and a constant, magnetic grin. The Lions’ resident rookie storyteller puts the homie in bonhomie. If there was an NFC symposium prom king vote, he would win in a landslide.

The rookies hear a message from HOF president Dave Baker before embarking on tours. The Lions and 49ers are paired together as one of the final groups.

Niners third-round center Marcus Martin, the youngest member of the team at 20 years old, arrives as the tour begins at 9:04 am. He overslept and had to catch a ride with NFL staff. The group passes an exhibit featuring an archaic football helmet from 1901 featuring a nose protector that is said to have done more harm than good.

"I swear on everything,” says Ebron, “I'd have been playing basketball."

They happen upon a mural boasting Art Shell as the first black head coach in the NFL’s modern era, in 1989. The rookies are incredulous.

“That’s crazy,” mutters one. “1989?”

“That’s like when Tupac got shot,” says another (he’s only seven years off).

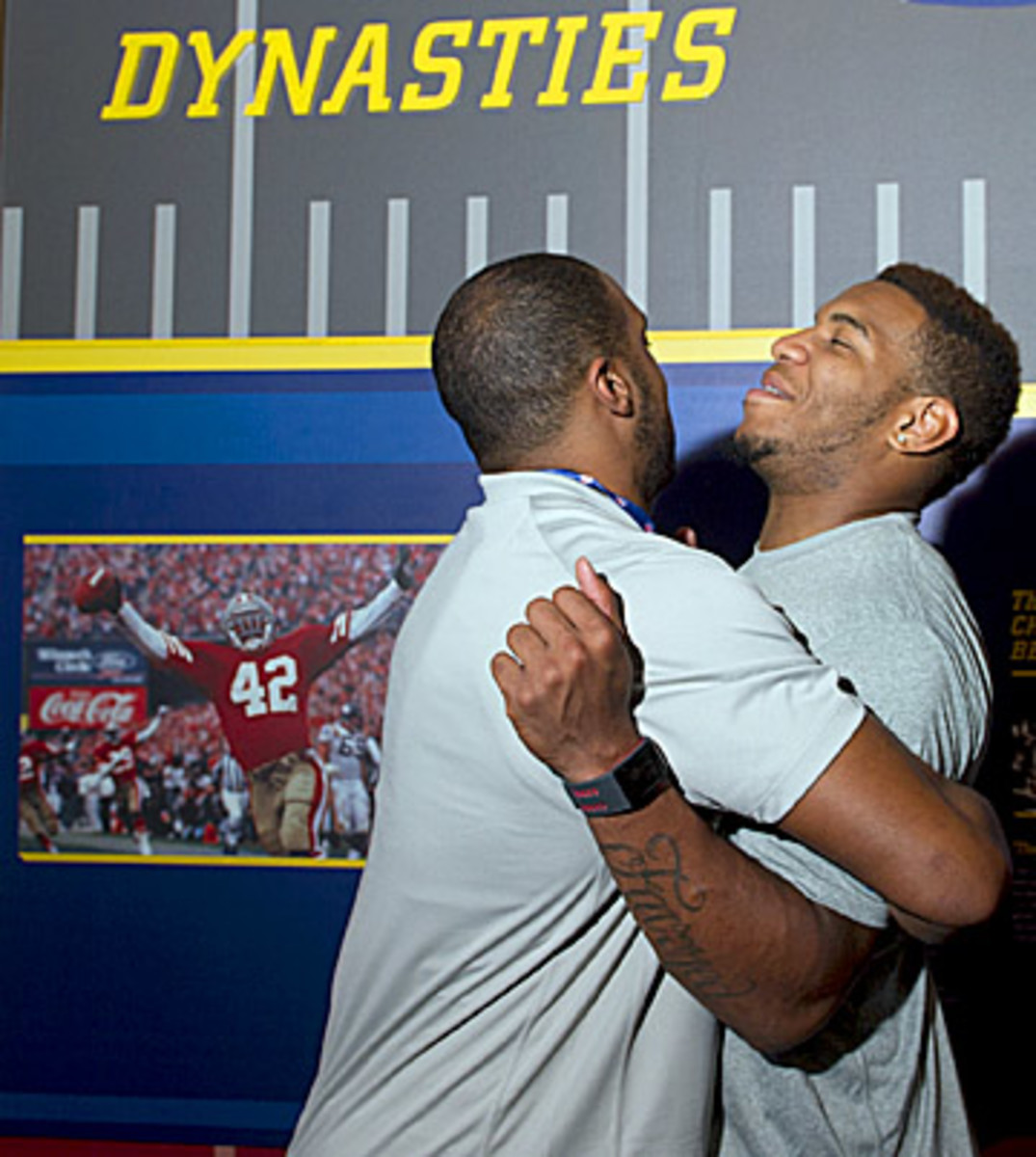

Ebron, the most outspoken rookie in the NFC group, is on the receiving end of a hug from fellow Lions rookie Larry Webster. (Phil Long/AP)

The tour moves slowly as the groups ahead create a backlog, but soon the Lions and 49ers enter the Hall’s holy grail—the dark, dome-roofed room filled with the bronze busts of every man enshrined. Most of the players skip the 1930’s, 40’s and 50’s and go straight to Lawrence Taylor, Class of 1999. A few hang back and click through the video boards showing highlights of every enshrinee. Lions defensive lineman Caraun Reid zooms to Colts legend Art Donovan, who attended his high school in the Bronx. In another group, Panthers defensive end Kony Ealy paced his teammates and supplanted the tour guide, rattling off positions and college and statistics for Hall of Famers going back to the 60’s.

Turner stops to admire the bust of Bill Walsh, the late 49ers coach. “I always have to see my guy when I go on,” he says.

Turner played linebacker for the 49ers from 1980-90, when Walsh and Dr. Harry Edwards started a resource for players’ lives off the field. At first, Edwards focused on degree completion, bringing in professors from the University of San Francisco to teach classes at the 49ers facility

“The whole idea of a resource at the club was Bill Walsh and Dr. Edwards,” Turner says. “At some point down the road the league adopted player programs, which became player engagement and spawned all of this.”

Ebron, relaying a story, is reminded not to say n——. Player Engagement reps gently remind players on their word choice dozens of times over the course of the symposium.

In another room, encased in glass, sits the next Lombardi trophy, which will remain in Canton until Super Bowl week in Arizona. Niners rookies agree to take a picture with the trophy, their team having been within a game of winning it in each of the last two seasons. Bruce Ellington thinks there in fact taking a video and breaks into a Nae Nae to everyone’s delight.

At Ebron’s urging, the Lions skip on posing with the trophy. “We don't even want to get near it,” he says. “We don't want to jinx it.”

They file up a curving ramp and into an amphitheater with two big screens and a rotating base of seats that spins the viewers 180 degrees as they take in NFL Films’ account of the 2013 playoffs, and the Seahawks’ domination of the Broncos in Super Bowl XLVIII. The Niners rookies file out uninspired. Someone else won the trophy half of them had just posed with. Why should they marvel again at the Legion of Boom four months after the fact?

Fourth-round cornerback Keith Reaser is especially annoyed: “I’m tired of hearing about the damn Seahawks.”

Back in the big lecture hall the players are getting antsy, wondering when it will all be over. Ebron, relaying a story to a fellow rookie 20 feet away, is reminded not to say n-----. In light of the league’s effort to eradicate the word, Player Engagement reps gently remind young black players on their word choice dozens of times over the course of the symposium.

“My bad,” Ebron says, “my brotha…”

The charter buses wait outside and several dozen autograph seekers have lined up along barricades guarded by smiling police officers.

Aeneas Williams ended the symposium with a speech that differed from those of his fellow Hall of Famers. (Phil Long/AP)

When Troy Vincent revamped the symposium, he brought in recent retirees who were his contemporaries. He also put an emphasis on men who shared his strong Christian faith. Hall of Famer Aeneas Williams, who will give the symposium’s final address, fits the bill on both counts.

“Think about how you want this thing to end,” says Williams. “Warren and Cris talked about making changes outwardly and not inwardly. When God changed my spirit, it wasn't that I was made perfect. The difference that Christ made is that there's now a thought before my actions.”

There are contradictions at work here, which Williams is bold enough to point out, and which seem to be inherent to the symposium. Beware of all women one speaker suggests, but treat all people as equals, says another. Do the right thing vs. Maintain the appearance of doing the right thing.

That the NFL has no problem with presenting these contradictions belies the homogenous reputation of the league. As the disparate career path of Hall of Famers Sapp and Williams will tell you, there's more than one way to skin a cat. And in putting both speakers in front of the rookies, the NFL recognizes the value of a shotgun approach in education, and concedes that asking this group to assimilate to one way of doing things is as arrogant as it is flawed.

He finishes with a request that all participants stand and chant after him, “Begin with the end in mind!” At his urging, it crescendos after a dozen repetitions, then fades as several in the back of the room begin to look at one another incredulously. Surely, this thing must end soon. It does, after maybe two dozen chants.

Four days after it started in a darkened hotel ballroom, the symposium ends at the doorstep of football's cathedral, under blue skies. The rookies file onto the buses, which will take them to the airport, which will lead to that critical month they've been talking about. They can smell what’s left of the summer.