Mike Holmgren is Retired

By Greg Bishop

KIRKLAND, Wash. — Mike Holmgren settled into the stands at CenturyLink Field last September. Nothing felt familiar, even there, in the stadium he helped build, with the team he helped save from relocation, with the organization he helped lift from the NFL’s basement to the Super Bowl.

He parked with the masses instead of in his old spot, the one nearest to the elevators. He fought traffic where a police escort once cleared the way. He met with fans in the hours before Seattle kicked off against San Francisco on a Sunday night in September, hours that for decades were whittled away in meetings and strategy sessions, football his lone focus.

He was there—and he was not.

“All of a sudden, I hear this big cheer,” he says. “This roar. And here comes Pete Carroll running out of the locker room.”

The roar bothered Holmgren more than he expected. It bothered him not because fans seemed excited to lose their voices for Carroll, the man with Holmgren’s old job title, that of Seahawks coach. It bothered Holmgren because for all the years he spent immersed in professional football, he could hardly remember a crowd reacting that way for him.

He’s sure it happened. He can recall the first time he jogged out of a tunnel to cheers that vibrated his eardrums. That was 1992, in Green Bay, against Kansas City in the preseason opener, his first game as an NFL head coach. His whole life pointed toward that moment. He bathed in the applause. I made it, he told himself. Only each subsequent roar registered a little less, until Holmgren ceased to hear them, until obsession overwhelmed moments that are supposed to be remembered.

What, then, when the career ends, when the grind stops, when years blend into decades and all that’s left is … something else? Holmgren is not the first coach to confront that question. Nor is he the first coach to react the way he did that night. He wanted to run down the aisle and climb over the railing and stand there on the sideline, his sideline, any sideline. He wanted that as much as he ever wanted anything. But his roar was gone.

Midway through the first quarter, he turned to his wife.

“Kathy, you want to go?” Holmgren said.

She nodded. They left. They went home. They watched the rest of the game, a 29–3 Seahawks rout, on television.

“You have these little epiphanies,” Holmgren says.

He knew that he missed football. On that night, at that moment, he knew how much.

* * *

Mike Holmgren is retired. He says that flatly, firmly, without hesitation. “I’m 65 years old,” he says. (In mid-June, he turned 66.)

* * *

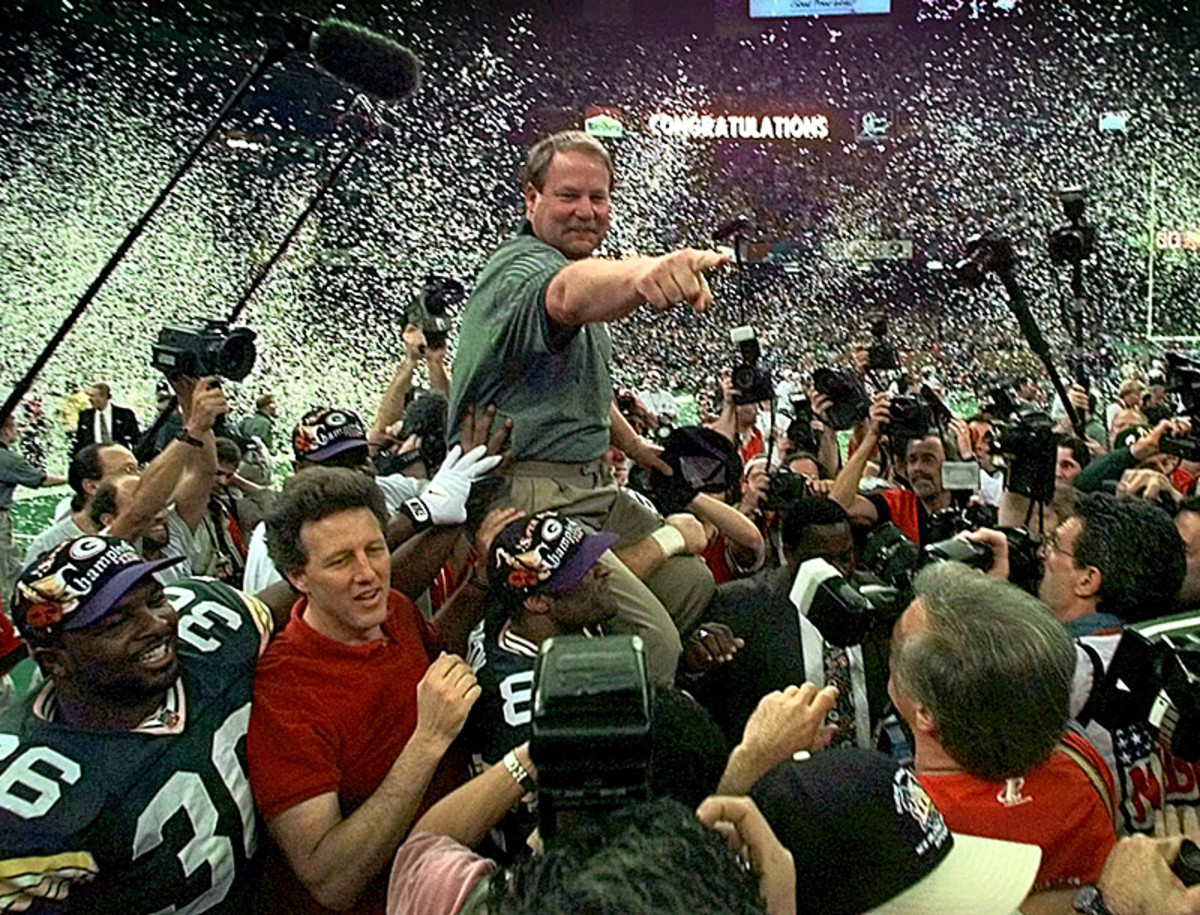

Holmgren reached the top of the football world with a victory in Super Bowl XXXI, leading the Packers to their first world title in 29 years. (Doug Mills/AP)

Mike Holmgren had never been fired. Not when he led the defense for a team—Sacred Heart Cathedral Prep in San Francisco—that lost 22 straight games. Not as he climbed from high school assistant to quarterback guru to mentor of Joe Montana and Steve Young and Brett Favre. Certainly not after he won Super Bowl XXXI with the Packers.

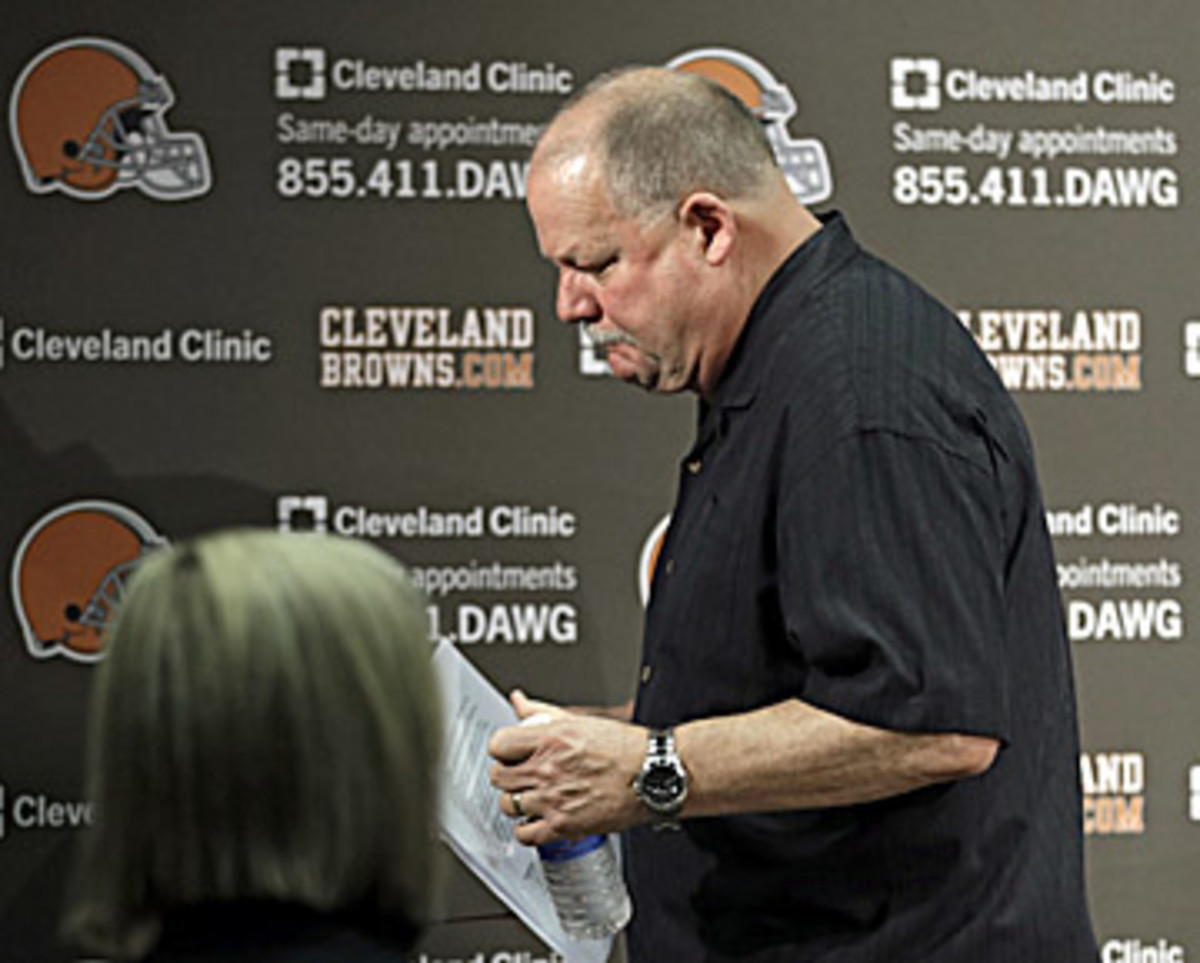

Then Mike Holmgren was fired, and by the Cleveland Browns, and after all of three seasons as team president. The Browns! Imagine that. A franchise mired in losing seasons and mismanagement, forever in search of its next quarterback. What a way for it to end.

He came back to the Seattle area in 2013, and the household that once bustled with four daughters now consisted of him, his wife and their dog, a Havanese puffball of white hair named Stella. Kathy had just returned from a mission trip to Uganda. Holmgren tried to settle in. He failed. “I was just a jerk,” he says. “Moping around the house.”

Kathy tolerated her husband’s mood for months. They share a desk in their office, and she listened to him on the phone, rehashing the whole Cleveland debacle, wondering what went wrong.

The Holmgrens start each morning the same way. They get up, work out at the small gym they built in a room in their condominium, read a devotional over coffee and plot the hours ahead. One morning after last Christmas, Kathy skipped the devotional. She had something else to say.

“It’s time,” she said. “I’ve given you your room, your space. Change the program. We have a lot to look forward to.”

“It probably happened about five times,” she says. “Then I’d hear him on the phone, and I’d sigh. Then he’s sensitive. It was like when he was having his hips operated on.”

Her: Do you have to tell everybody you just had your hips done?

Him: I don’t do that.

Her: Yes, you do.

She once heard that LeBron James called a childhood friend his Keep It Real Guy. That's what she is to Mike. They met at summer camp in Santa Cruz, Calif., at age 12. He first proposed at age 15. (Her response: “Nope.”) They went to different high schools and different colleges but saw each other every summer. He proposed during his junior year at USC, just a simple Will you marry me? and she said yes.

She laughs on the deck outside the condo as she relays all this, steps from the water, from the dock and her orange kayak and his powerboat. Stella barks at the strangers who jog the path nearby. It’s early June, the morning of their latest wedding anniversary. No. 43, or XLIII in football parlance.

“He got retired,” Kathy says. “If I used that word, it bothers him a lot. To think that he got fired.”

When Holmgren started coaching in the early ’70s, Kathy had no idea just how all-consuming football would become. They had twin daughters, and Holmgren, stuck in that big losing streak at Sacred Heart, wondered if his fellow coaches would gift him with a game ball. “Maybe you can win,” she quipped, and they lost that next game by what seemed like 50 points.

Holmgren earned higher-profile jobs. The salary increased. So did the perks. He guided the offense at Oak Grove High School in San Jose, with Marty Mornhinweg, now the Jets’ offensive coordinator, as his quarterback. He jumped from high school teacher who moonlighted as a football assistant into the college ranks, first at San Francisco State, then at Brigham Young.

The Holmgrens made time for each other, despite the job's demands: hot dog lunches on Tuesdays while he was at BYU, Thursday family dinners while he coached with the 49ers.

Eventually, every minute of his day was scheduled, even the family dinners. Before retirement, Holmgren could tell someone in June where he would be the next Oct. 7, at 9:20 a.m.—which room, which chair, which visitors.

In October 2012, Holmgren announced he would be retiring as the Browns' team president at the end of that season. It was not his choice. (Mark Duncan/AP)

Even if it took him longer to move on from losses over the years, Holmgren became intoxicated with the job and all the status that conferred, the private planes and handlers, the best tables in the best restaurants. For Cleveland, he often attended the owner’s meetings, billionaires all around, perhaps the most selective table in sports. Jerry Jones of the Dallas Cowboys passed him a note at one of those meetings:

If any of this stuff is over your head, just see me afterward, and I’ll clear it up for you.

Holmgren scribbled a response and passed it back.

You’re still trying to figure out what pass interference is.

Then it ended. “He didn’t choose to retire,” Kathy says. “He got retired. If I used that word, it bothers him a lot. To think that he got fired.”

* * *

Mike Holmgren is retired. He says that again, but adds, “I know guys who coached after 65. I thought I would. The more I’m moving away from it, it’s flattering when you get a call from somebody. It strokes your ego. Then you start to think, Hey, I could do that! I mean, I miss it. I miss the coaching. I miss it.”

“I’m quote-unquote retired,” Holmgren says later.

“I’m semi-retired,” he says after that.

* * *

Outside the Highland Covenant Church in Bellevue, Wash., on a Tuesday afternoon in June, a line snakes down the stairs and around the block. It’s 3:30 p.m. There are women with strollers, old men with teenaged grandsons and several families conversing in Russian.

They’re here for the Renewal Food Bank, a program started by Rich Bowen in 1997. Bowen is a lifelong Indianapolis Colts fan. He says he tried to convert Holmgren in retirement—and failed.

The food bank is open on Monday and Wednesday mornings and on Tuesday afternoon. It works like a grocery store, except it’s free food for the less fortunate. Families come in and select from certain donated items.

Holmgren volunteers there. He arrived that Tuesday in his new retirement uniform: blue cargo shorts, light blue Bermuda shirt, sandals. Like he’s headed for the beach.

His job is to replenish three bins set up on a folding table. One bin is for meat, another for dairy and another for fresh produce. Some of the items are frozen. None of the shoppers seem to notice that Holmgren went from the frozen tundra in Lambeau to the frozen food section here.

He’s into it regardless. He says things like “these are little yogurts” and “we have Jamaican style chicken, good stuff.” No one asks about Montana or Favre or his Super Bowl rings. And he jokes that this is the only job he’s qualified for now.

If they’re being honest, Holmgren thinks that coaches envy someone like Joe Gibbs. He went from football into auto racing. He can still experience the thrill. He can still hear the roar. He can retain what Holmgren lost, what all retired coaches lose. “Most of us fail at trying to duplicate that,” Holmgren says. “A better way to go is trying to be honest with yourself. Saying, I’m not going to find that anymore. I’m not going to find that again.”

Coaches exit those every-minute-planned orbits and need something else to do. Sherman Lewis coached with him in San Francisco and became his offensive coordinator in Green Bay. Lewis grew roses even while he was working. He would stop home during breaks in training camp to water flowers and spray for pests. When football ended, Holmgren needed to find his own hobbies, something like Lewis’s roses. He needed to fill the time that football once consumed.

Now, he plays spider solitaire. He spends time with his nine grandchildren and three of his daughters who live nearby. One grandchild took him to show-and-tell; another on a class field trip. He reads a lot of fiction, Daniel Silva and Nelson DeMille and John Sandford and Lee Child.

He visited Israel with Kathy and came home and re-read the Book of Exodus. He took a mission trip to Guatemala and built stoves and huts in the mountains. He wants to play more golf, after he recovers from two hip replacements done in the past year. Kathy even purchased him a book—about hikes for people with weak knees. “Walks for old people, basically,” she says.

A new Sunday routine replaced the old one. Holmgren attends church with his extended family—one son-in-law is the pastor at Highland Covenant—the whole lot of Holmgrens in the back three rows on the left-hand side. He’ll take them all out for burgers at Red Robin and return in time to watch the Seahawks. Then 60 Minutes. Then off to bed.

Holmgren thinks that coaches envy Joe Gibbs. He went from football into auto racing. He can still experience the thrill. “A better way to go is trying to be honest with yourself,” he says. “Say I’m not going to find that again.”

This is not the Mike Holmgren that we remember, stalking the sideline in coach-issued khakis, face red, eyes narrowed at some unfortunate soul who dropped a pass or missed an assignment, top forever blown. This Holmgren rarely watches game tape or highlight shows. He works in radio to fill the football void but turned down job offers to X and O for Fox Sports 1 and the NFL Network. This Holmgren picked family over football, for now.

And still, he cannot let go. None of them can. He doesn’t want to. Not yet. “I’m not just going to stop with football,” he says. “I don’t think that helps, either.”

Holmgren went to Canton, Ohio, to watch Bill Parcells go into the Hall of Fame last year. He will do the same this summer when Walter Jones, the great Seahawks left tackle, is inducted. He still talks personnel with old friends. Like Ted Thompson, general manager of the Packers.

“Ted’s the original Marlboro Man,” Holmgren says, his voice wistful. “Sitting on a horse. Out by himself. Love him! You have a conversation on the phone with him, and there’ll be these big pauses. He’s watching tape. Love it!”

* * *

Mike Holmgren is retired. Probably. Maybe. “If some unusual thing happened, Kathy and I would talk about it,” he says.

* * *

Inside the studio at 950 KJR in downtown Seattle, Mike Holmgren is easing into his new life, one toe still planted in the sports world. There’s that uniform again: cargo shorts, Tommy Bahama button down, sandals—beach ready.

He’s talking about that time he struck out in ninth grade, bases loaded, his father, the real estate agent who never had time for anything but work, in the stands. He cried for hours afterward.

“Were you fiery?” asks the host, Mitch Levy. “Were you fiery in ninth grade?”

“I was always fiery,” Holmgren says.

Everybody laughs.

He’s talking about sports, how everyone gets knocked down, how everyone gets fired. He’s talking about Steve Ballmer, who purchased the Los Angeles Clippers that week, and the world that Ballmer is stepping into, the expectations, the other owners, all that pressure to lead others to perform.

He’s talking about the NFL’s “marijuana problem.” He doesn’t think the league should be more lenient. He thinks maybe 20% of the players smoke pot recreationally. One of his former players, Cleveland wide receiver Josh Gordon, was suspended after a positive test for the drug, according to an ESPN story.

He’s talking about the Redskins. He thinks they should change their name. He’s talking about Johnny Manziel’s trip to Las Vegas, about how Manziel’s shrug of a response at a subsequent news conference bothered him the most. “You can think that,” Holmgren says. “You don’t have to say it.”

This process, for Holmgren, seems cathartic, a way to stay around football and around sports when the door he sort of wants back open—back to coaching, back onto another sideline—remains closed. He spent enough time at the forefront of professional football, of professional sports, that all roads lead back to him in some fashion. Ballmer is a Seattle guy; Gordon plays for the Browns, who drafted Manziel, who fired Holmgren; he knows how league executives feel about the Redskins. It’s like Six Degrees of Mike Holmgren. Only three would probably be sufficient.

Radio appearances are one thing that keeps Holmgren close to the sports world. (Rod Mar/Sports Illustrated)

Holmgren used to dismiss the notion of a coach’s shelf life. He loved the strategy involved, the day-to-day intensity of that existence. He would have done it forever if he could have. That’s all true, but his opinion has shifted. He’s not happy with all the rule changes, with how Commissioner Roger Goodell seems to dictate to the Competition Committee that Holmgren once served on. Holmgren says he likes Goodell, but he also says the commissioner used to make suggestions instead of mandates. He says that when you reach curmudgeon status, it’s probably time to go.

Kathy understands her husband, so she understands the longing, the need, at his core, to be needed. She reminds him of the two goals he stated he wanted to accomplish at the outset: to become an expert in quarterback play and to be respected by his peers.

Then she reminds him that his dad died at 48, her dad at 51.

* * *

Mike Holmgren is retired. He says he is one of the lucky ones, a man who did what he loved for a long time. He says the trend is to hire younger coaches now. His contract with Cleveland runs out next February.

“That will be it, pretty much,” he says. “Unless something big comes up.”