The Secret to Being a Good O-Line Coach is C.O.O.L.

CINCINNATI – It’s nearly 2 a.m. on a Friday night in May. There aren’t many people left in the closed down bar/restaurant that inhabits the top floor of the past-its-prime Millennium Hotel. The skyline of the Queen City twinkles in the background. You can see Paul Brown Stadium.

A circle of about eight chairs has formed in one corner of the room. Legendary retired offensive lineman and coach Howard Mudd is seated in one. Dan Dorazio, the offensive line coach for the B.C. Lions of the Canadian Football League, is in a chair near Mudd. They are discussing the finer points of the silent count, of which Mudd is the godfather from his days as an assistant coach with the Colts and Peyton Manning.

“Did you rely on a guard to tap the center?” Dorazio asks Mudd. In the offensive line world, it’s like asking Michelangelo how he went about painting ceilings.

“No, we didn’t do that,” Mudd says. “I’ve seen that done, people are doing it. It seems like it slows it down to me. We did the silent count under center and from shotgun. [Center] Jeff Saturday would either look through his legs for the indicator, or feel a tap on his ass [from the quarterback]. Then the center would lift his head and have a count in his head. He couldn’t even start counting until his head stopped. The other guys could see his head come up. They didn’t have to see the ball go.

“Now this thing about tapping. If I’m the guard, first of all I can’t be in a stance—I want my guards in a stance—and I have to look at the quarterback, see [the indicator], tap the center, then I have to come back and find my guy. Why are we making one guy blind when we don’t have to? I’m concerned about that.”

Dorazio nods.

“We have the guard extend his elbow and just touch the center on the hip, so he doesn’t have to take his eyes of his guy,” Dorazio says.

“He still has to look at the quarterback to get the indicator, right?” Mudd replies.

“Initially, yes,” Dorazio says.

“Most of the time the center isn’t covered [i.e. doesn’t have a defensive player in his face],” Mudd says. “My concern is you’re asking a guy who is covered, to go look back here, hand out, not hand out, so I didn’t do it. The guards could help the center, if the [middle linebacker] was moving around, tell the center where he was.

“We just didn’t have any problems with it. None. There were never any problems. I tried to get them to try other stuff like that, but Peyton and Jeff would freak out. ‘Noooo! What’s wrong with what we’re doing, there’s nothing wrong with it!’ We were so good at it that Peyton wanted to use the silent count at home—we had less problems with it than a cadence. I still think there’s a risk turning around with a man in front of you."

Dorazio tries explaining his rationale again, in a different way. This goes on for another 10 minutes.

“To me, it overly complicates it,” Mudd says. “That’s my two cents.”

Welcome to the Coaches of Offensive Linemen (C.O.O.L.) clinic.

* * *

For as long as anyone can remember, offensive line coaches have been in the sub class on coaching staffs. If you’ve ever attended a training camp practice, you've seen the big hogs practicing off by themselves in some far-flung corner, doing their own drills against each other. Before the advent of million-dollar training facilities that now dot the NFL, the offensive line was often relegated to the worst field, one that was barely maintained. They only get the call to work on the main fields during 11-on-11 work, or the occasional middle run drill. After that period is over, they trot back to their corner. Half the group picks up a blocking bag and imitates a defensive lineman. The other half goes through the reps of blocking a particular play.

Howard Mudd coached the Colts offensive line from 1998 through 2009, helping keep Peyton Manning protected. (Al Pereira/Getty Images)

There aren’t coaches for each place along the line—like one for tackles, another for interior linemen, etc.—as with just about every other position. There is one coach, and he might be lucky to have an assistant, for the five starters plus several backups.

When it comes to formulating play books and game plans, the offensive line coaches also get the short end of the stick. They’re often taken for granted. Bob Wylie, who has instructed at all levels of football from Pop Warner to the NFL and now the CFL, recalled once flipping through a playbook and seeing that the five circles for his unit had been replaced by one horizontal line.

“What the hell is this?” Wylie asked the coach.

“You’ll get it blocked up,” he replied.

“How do you want it blocked?” Wylie asked.

“You figure it out,” the coach said.

It’s no wonder, then, that the logo for the annual C.O.O.L. clinic, is a mushroom. It’s on everything: the overhead projector, golf shirts, Mudd’s T-shirt, travel bags and even cookies.

“They keep us in the dark, feed us s--- and expect us to grow,” Wylie says proudly. He has run the clinic since 1995. “We’re fungus, basically.”

And here, in the expansive ballroom of the Millennium, the mushroom assemble to grow together. They don’t get much help from their own staffs, so they congregate to share the techniques they’ve tried that have led to great success, and also some failures. It’s a support group, and one that’s damn proud.

“I don’t know if you appreciate this,” FSU offensive line coach Rick Trickett tells the crowd. “This is a hell of a get together. If you don’t find somebody to latch onto here, find somebody. This is what we do. We help each other.”

* * *

What now draws more than 400 coaches started in the Bengals offensive line room in the early 1980s when Jim McNally, the noted retired line coach who had success with the Bengals, Panthers and Bills, hosted about six other coaches (including future Cincinnati line coaches Paul Alexander and Wylie) to talk about and draw blocking schemes. The next year there were 18 in attendance. It didn’t take long for owner Mike Brown to frown upon the idea of the Bengals’ secrets being given out, so the get-together was taken off campus.

We all learned things from someone else, and I think it's a duty of a conscionable human being to give back," Bengals line coach Paul Alexander says. "And I think offensive line coaches, by and large, are more conscionable than others.

McNally is a bit of a guru in line circles. When Dante Scarnecchia became a line coach in 1989 with the Colts, the first thing he did was make a pilgrimage to Cincinnati to pick McNally’s brain. McNally, who’s 70 but is still in fantastic shape and enthusiastically demonstrates blocking techniques, hosts an offensive line retreat annually for those interested in further study.

Normally, the C.O.O.L. clinic reserves the anchor speaking position each day (Friday for college coaches, Saturday for NFL) for the coach of the reigning champions. Florida State line coach Rick Trickett gave an outstanding and often hilarious dissertation on the Seminoles’ stretch runs from different formations. Unfortunately, with the NFL draft pushed back this year, Seahawks line coach Tom Cable could not follow through on his previous commitment because of rookie camp. So it was legends Saturday at the clinic: Dante Scarnecchia (Patriots), Tony Wise (Cowboys), Wylie, Mudd, Jim McNally (ex-Bengals), Paul Alexander (current Bengals) and Dan Radakovich (Steelers).

From February through March, coaching clinics are held throughout the country. There are big, multi-city clinics like Nike Coach of the Year and Glazier, along with regional migrations like the Big New England. Attendees ranging from top high school coaches to NFL assistants get together to share their honed tricks of the trade. These sessions, normally conducted out of sight of media and very much off the record, are like traveling carnivals. You’ll smell cookies being baked in the hallway, bait to get a coach to hear a sales pitch on uniforms, pads, game-film programs, books, etc. A lot of networking happens. But at the heart of these clinics is a shared love of the game and commitment to learning how become better coaches.

All these tips, all these tricks, all this wealth of knowledge and years being shared—you don’t see offensive coordinators getting together to swap secrets, that’s for sure.

“We all learned things from someone else and I think it's a duty of a conscionable human being to give back," Alexander says, adding with a laugh, "and I think offensive line coaches, by and large, are more conscionable than others."

I’ve attended my share of coaching clinics the past four years, strictly to educate myself on the game and what’s next. Stanford offensive coordinator Mike Bloomgren told me a year ago that I had to go to the C.O.O.L. clinic.

“It’s the best, by far,” he said.

* * *

Bloomgren was right. To know line play is to know football. The game is won and lost there. And I’m guessing most fans have little idea the intricacies of what goes into line play. The players might look like dancing bears on the line, but every movement is choreographed for the feet, hips and hands. One false move can blow up an entire play, ruin a series and lose game.

Dante Scarnecchia worked for the Patriots for 30 seasons, including a 15-year stint as offensive line coach from 1999-2013. (Elise Amendola/AP)

It’s enlightening to hear coaches talk (mostly over my head) about the training and techniques that go into line play. Most fans only know the offensive linemen if they do something bad. But, when performed correctly, line play is a work of art. A guard on the playside (where the play is going) needs to know what to do if there’s a defensive player in front of him (covered) or not (uncovered). If he’s covered, he has different techniques that are dependent on which way the defender moves. Then he might have responsibility for a linebacker after the initial push. And the rest of his linemates have to know exactly how he’ll react and block his own responsibility as well. It’s no wonder offensive linemen routinely have the highest Wonderlic scores of any position except quarterback, and go on to be coaches. These are not just giant slabs of beef.

And the level of their instruction matches their intelligence, especially if they have a coach like Trickett. He makes players flip positions for a few days to rejuvenate them.

“Those tackles do not like going back in to guard, I can promise you that,” Trickett says. “They think they have their stuff down. They go inside and they say, ‘Stuff happens a lot faster.’ Well, no s---. Try playing center. They like it outside. Of course they do. Any moron can play tackle. It’s all man on man out there. How complicated is that?”

Scarnecchia gave a dissertation of the Patriots’ wham/blast/bong power running game. He noted that the wham play started when he, Charlie Weis and Bill Belichick arrived at New England and married the Ron Erhardt and Joe Gibbs schemes.

Scarnecchia also gave a piece of advice that runs counter to the popular opinions that you run to se tup the pass, or pass to set up the run. What the good teams do—particularly noticeable with Peyton Manning or Tom Brady at quarterback—is run play-action not off runs, but instead to protect core runs. As soon as an offense sees the linebackers running down hill quickly to stop the runs, Scarnecchia says to hit them with the play-action. Not only will it likely result in a big play, but those linebackers will not be playing as fast the rest of the game.

Mudd, who demonstrated techniques despite being hobbled by injuries from his playing days with the 49ers and Bears, laid out many of his proven beliefs. For instance, he believes in blocking every play like a play-action pass with short sets by the linemen. And that “character and intelligence separates the players.”

They keep us in the dark, feed us s--- and expect us to grow," Wylie says proudly of the way teams treat O-line coaches. "We're fungus, basically.

Even the older offensive line coaches never stop learning. Scarnecchia sat with Bloomgren and Bob Connelly (Oklahoma State) while Mark Staten (Michigan State), Josh Henson (Missouri) and Trickett explained their view and how they teach zone runs. “I don’t think we said 20 words to each other in three hours listening to those guys,” Scarnecchia says. “You may not agree with everything, but you’re picking up certain things here and there. This is what it’s all about. That’s what these clinics are about.”

Most know that offensive line coaches love wrestlers because they understand leverage and are good athletes. That still holds true, but there is growing influence by the martial arts world on offensive line techniques. Alexander, whose Bengals have consistently been one of the NFL’s best units, teaches his charges to get their hands on the arms of defensive linemen to redirect them, or use a club move, instead of the time-tested punch at the point of attack. Alexander wants his guys to win before that point with their hands. When his players encounter a rusher who leads with one shoulder, Alexander wants them to get their arm extended on the outside to spin the rusher “like a top” by using leverage. Pushing just on the shoulder wouldn’t have nearly the same effect as a concentrated, angled blow. And the Bengals should never get stuck (held) by an outside rusher. They are trained, thanks to Judo techniques, to deflect the block and move around.

So much for the, “You block that guy,” from the old days.

Actually, there was a little of that, from Dan “Bad Rad” Radakovich, who was the Steelers’ defensive line coach for Chuck Noll in 1971, and O-line coach from ’74-77 (two Super Bowl titles). At 79, Radakovich is gruff, tough and intimidating. He’s a bit like Izzy Mandelbaum of Seinfeld fame—at any minute you expect him to point at you and ask, “You think you can lift more than me? It’s go time.”

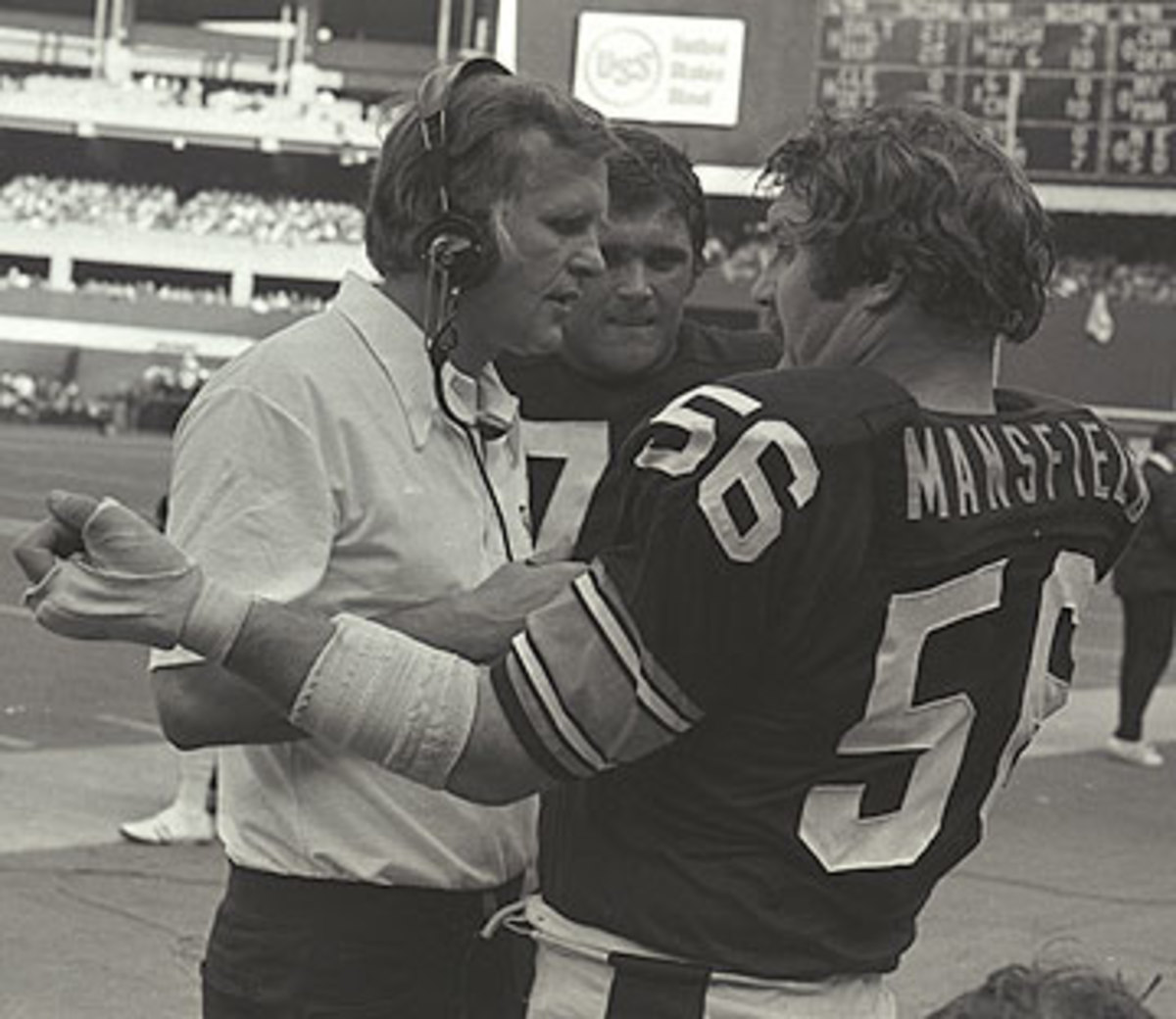

Dan Radakovich, here with Steelers center Ray Mansfield, coached football for 48 years before retiring in 2008. (George Gojkovich/Getty Images)

Radakovich, who showed some great old practice film of the Steelers, had two coaching interns run through drills just about at full speed. Radakovich was no fan of many of the new-school techniques taught at the clinic. “Just drive block them,” he says.

Just as he was finishing, someone told Radakovich he'd forgotten to show the door drill. He immediately walked quickly to the large and heavy doors to the side of the ball room.

“You want to try to break his nose,” Radakovich instructed, without the slightest hint of a joke.

An intern got into blocking stance with one hand on the ground.

“Ready, hut!” Radakovich barked.

The intern sat back into his blocking stance as Radakovich swung the door at full speed. The intern punched his two hands out to stop it, looking exactly as an offensive lineman should.

“That’s the door drill,” Radakovich grumbled.

And that’s the C.O.O.L. clinic. Offensive line coaches, whether they’re old school or new, are a different breed. Or maybe it’s a different species of fungus.