Stem Cell Treatment: Out from the Shadows, Onto the Cutting Edge

New Jet Chris Johnson had stem cells from his bone marrow reinjected into his knee to augment January surgery for a torn meniscus. The hope is that it would boost healing and perhaps rebuild cartilage. (AP)

He’s 28. He has five 1,000-yard NFL rushing seasons to his name, one 2,000-yarder and a burning desire to prove he’s the same speedster he’s always been. So when Chris Johnson visited orthopedic surgeon James Andrews in January to fix his ailing left knee, he liked the sound of two intriguing words: Stem cells.

The veteran running back tore the meniscus in that knee in Week 3 of the 2013 season—his last with the Titans before being cut—but never missed a game. The injury to the knee’s natural shock absorber also caused other damage in the joint, and Andrews presented an option that might augment what surgery alone could do. The plan: Take stem cells, the body's universal building blocks, and deliver them directly to the construction site.

“When I tore my meniscus and played the season out, through the wear and tear, I lost a lot of cartilage,” says Johnson, who was signed by the Jets to bring explosiveness to their offense. “When you put the stem cells in, it might be able to help rebuild that cartilage in your knee. Hopefully, it makes your knee better for even more years.”

On the day of his surgery at the Andrews Institute in Gulf Breeze, Fla., Johnson had a small amount of his bone marrow—60 milliliters, or the volume of a shot glass—siphoned out of the iliac crest of his pelvis with a long needle pushed through a tiny incision in his skin. Less than an hour later, at the end of the arthroscopic procedure to repair his meniscus, a concentrate of thousands of stem cells from the bone marrow was injected directly into Johnson’s knee joint.

Instead of the usual four-to-six-week recovery time from the scope, Johnson stayed off the practice field for the rest of the offseason, giving the stem-cell treatment maximum time to work. At the least, stem cells are a powerful anti-inflammatory. But the hope is they may also play a role in boosting the healing of injured tissues, including stubborn ones like the meniscus, which lacks a robust blood supply, or cartilage, which has long been irreplaceable.

Stem cells are far from mainstream—NFL teams will often not pick up the bill, and the overseas market for treatments not approved in the U.S. makes the whole field seem somewhat taboo.

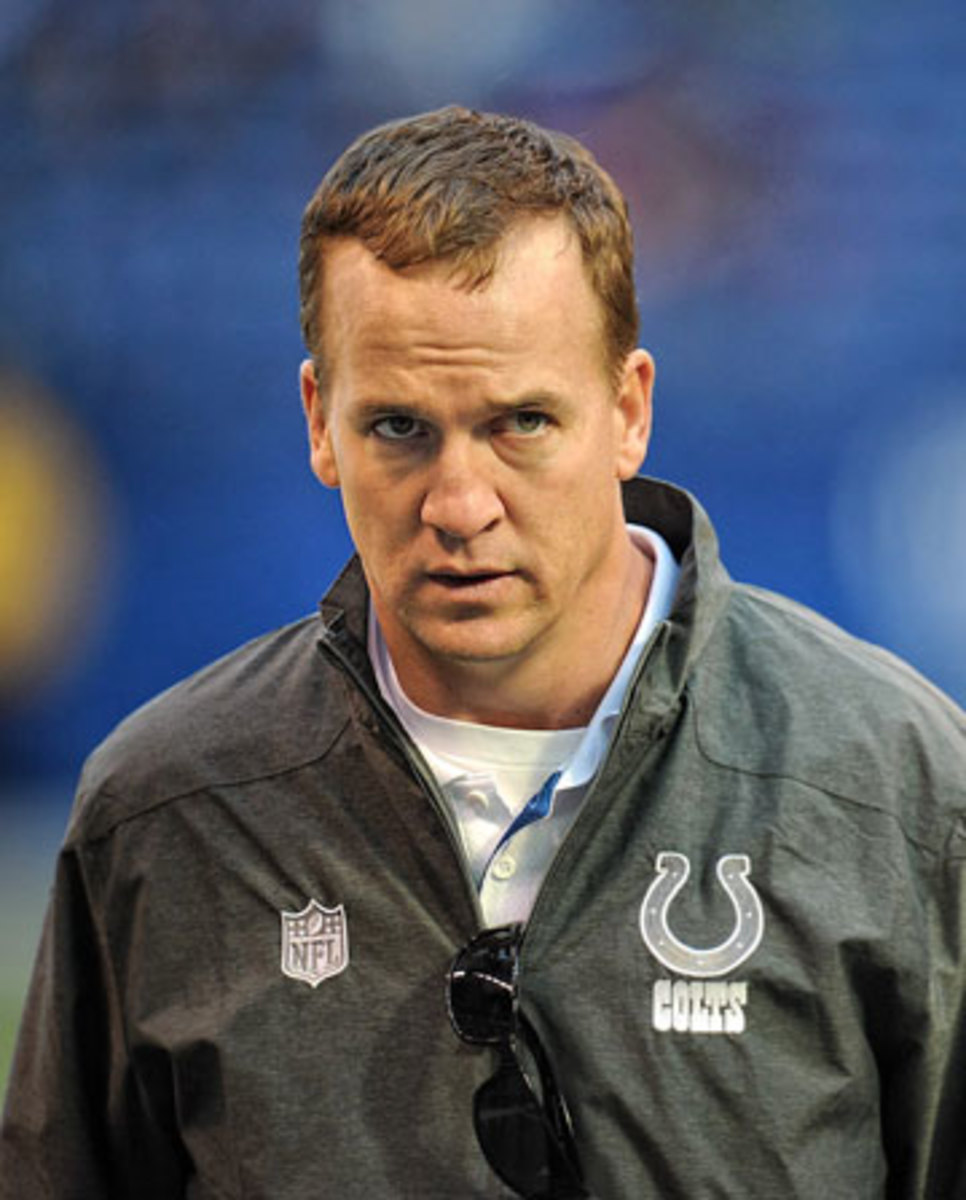

Johnson is one of hundreds—yes, hundreds—of NFL players who have invested in the promise of stem cells in the past few years. Peyton Manning reportedly tried a stem-cell treatment in Europe in 2011, his final year with the Colts, to fast-track his recovery from neck surgery. Giants cornerback Prince Amukamara had a slow-healing broken metatarsal treated with stem cells by a foot specialist in North Carolina after his team’s Super Bowl XLVI run. One NFL linebacker paid $6,000 a pop for a 1-milliliter vial of donated placenta tissue containing stem cells to be injected into each of his beat-up knees this offseason—but asked for his name not to be used in this story because he didn’t tell his team’s medical staff.

Such treatment is more common than you might realize among NFL players (hundreds of players across 32 teams averages to at least six players per team), but it’s also far from mainstream. Stem cells are still somewhat in the shadows—evidence of their usefulness in treating athletes’ injuries is so far largely anecdotal, NFL teams often will not pick up the bill for players, and the overseas market for treatments not approved in the U.S. makes the whole field seem somewhat taboo.

There’s a push to change that, though, and Andrews is an important figure at the forefront. His group is currently building a laboratory at its Florida facility specifically dedicated to biologics—the term refers to substances that are produced in living systems such as humans, animals and microorganisms, rather than manufactured like drugs—to be able to offer their star-studded clientele more of these treatments more effectively in the U.S. The agenda includes a research study with retired NFL players on how well stem cells work in treating arthritis of the knee; a trial of a Malaysian technique for regenerating cartilage by using stem cells from the blood after microfracture surgery; and exploring whether torn ACL tissue can be repurposed to help the new ligament graft heal more quickly.

“We have had one big revelation in sports medicine over the last 50 years, and that was the arthroscope,” Andrews says. “I’ve been looking for the next wave, and I think the biologics, particularly stem-cell therapy and enhancement of the healing properties, will be it.”

But, he adds with frustration, “We’ve been saying that since the new decade of this new millennium, so we’re already behind.”

* * *

Dr. Josh G. Hackel of the Andrews Institute performs a bone marrow aspirate injection to an arthritic knee under ultrasound guidance. (Courtesy of the Andrews Institute)

The stem cells used to treat athletes’ injuries are not the same kind as those steeped in ethical and political debate in the U.S. The latter are the human embryonic stem cells derived from unused embryos at in-vitro fertilization clinics, whose use in research has been contested over the past decade, all the way up to the Oval Office.

Stem-cell treatments for athletes, on the other hand, use the adult stem cells we all have in our own bodies. These are unspecialized cells that have the ability to produce new cells, mature into a variety of different cell types and mobilize in response to an injury. Orthopedists have been particularly interested in mesenchymal stem cells, found in sources such as bone marrow and fat tissue, which can become new bone, cartilage, muscle or connective tissue—the cogs in the machines of athletes’ bodies.

Andrews quietly has been using these stem cells to treat pro athletes for about three years. The count of NFL players he’s treated with stem cells is a couple hundred, he admits, but, wary of sensationalizing, he adds quickly, “that’s not the right question for right now.” Some receive an injection to control swelling in a troublesome knee or shoulder as an alternative to a cortisone shot. A smaller number have had stem cell treatment in tandem with a surgical procedure on harder-to-heal injuries, like Johnson’s. (It’s not routine for ACL surgeries, so no, Adrian Peterson’s warp return wasn’t aided by stem cells). “Most of the athletes know about this, and they are coming in and asking for it,” Andrews says. Some teams send players to him for treatments.

It’s perfectly legal in the NFL and the other major professional sports leagues. The NFL considers stem cells a medical treatment—not a performance-enhancing substance—just as with platelet-rich plasma (PRP), the blood concentrate that advanced the biologics movement when Steelers receiver Hines Ward used a form of PRP treatment to come back from a medial collateral ligament sprain in time for Super Bowl XLIII.

But the kind of stem-cell treatments players are getting varies greatly. Andrews and his team of doctors have been limited in what they can offer by a strict adherence to guidelines from the Food and Drug Administration. So far, that’s meant sticking to one procedure: Harvesting cells from a player’s bone marrow and putting them back into his or her body, unaltered, at the site of injury.

Manning has never acknowledged whether he went overseas for stem cell treatment to address the neck injury that made him an observer for the entire 2011 season. (Andrew Hancock/Sports Illustrated)

In other countries, though, stem cells can be taken out of a player’s body and cultured over a 10-to-14-day period. The benefit? This procedure, illegal in the U.S., grows thousands more of these prized cells, meaning that one draw of bone marrow may yield around two million mesenchymal stem cells, instead of just 10,000. Steelers team orthopedic surgeon Jim Bradley, long a champion of biologics—he injected Ward with the PRP—presents this overseas option to players who ask about stem-cell treatment. He’s gone so far as to visit one particular international lab multiple times to feel comfortable vouching for it.

“This is why people go to the Cayman Islands, to Russia, to North Korea, to Japan, to Germany, because we can’t multiply stem cells here,” Bradley says. “When my NFL guys ask me, ‘Where would I go for this?’ I have a very good answer for them. I’m not going to tell you where I tell them to go, but it is not in the U.S.”

The enticement of next-level healing for million-dollar athletes has also spawned a cottage industry of biologics companies, each advertising products they claim are the best on the market. Here’s one example: Steven Victor, a dermatologist to celebrities, became involved with stem cells while seeking a use for discarded fat tissue from cosmetic procedures. He traveled to Greece for instruction, patented a technology in the U.S. that uses sound waves to isolate stem cells from the fat, and started the Park Avenue-based IntelliCell BioSciences. He’s treated current and former NFL players—Merril Hoge is a spokesperson—and, recently a Dubai businessman called about using the procedure to heal his high-priced thoroughbred racing camels.

The cost of one stem-cell treatment starts at about $5,000 in the U.S., and between $15,000 and $25,000 overseas. Athletes pining for a fix to the ailments threatening their careers are willing to pay that price, even if it’s out of pocket—as was the case for the linebacker who didn’t want his name used. Multiple surgeries left his knees chronically swollen and aching, so he turned to a treatment recommended by his orthopedic therapist and a handful of teammates.

“Body parts in a cryogenically frozen cooler,” he says. That’s not entirely accurate, but the treatment he received, from a Colorado-based biologics company, illustrates the wide spectrum of stem-cell therapies NFL players are using. The product in the vial didn’t contain the player’s own freshly harvested stem cells, but rather liquefied placenta tissue with stem cells and growth factors, donated by a new mom after childbirth and frozen at minus-80 degrees Celsius. (His orthopedic therapist says he has sent 150 NFL players to get this treatment in the past year and a half).

The linebacker didn’t tell his team mainly because he didn’t want to jeopardize his roster spot by arousing concern about the health of his knees. But he’s not alone in wanting to keep his stem-cell use private. Manning has never talked publicly about his reported trip to Europe for stem-cell treatment, and a team spokesman turned down a request for this article.

“It does kind of sound like you’re talking about illegal gambling or a pharmaceutical drug trade or something,” the player says. “You hear about labs being set up in Bermuda to avoid the laws here, and all these small companies claiming to have the best product. Guys are just looking for who is at the tip of the sword, and you don’t want everybody to know your secrets.”

* * *

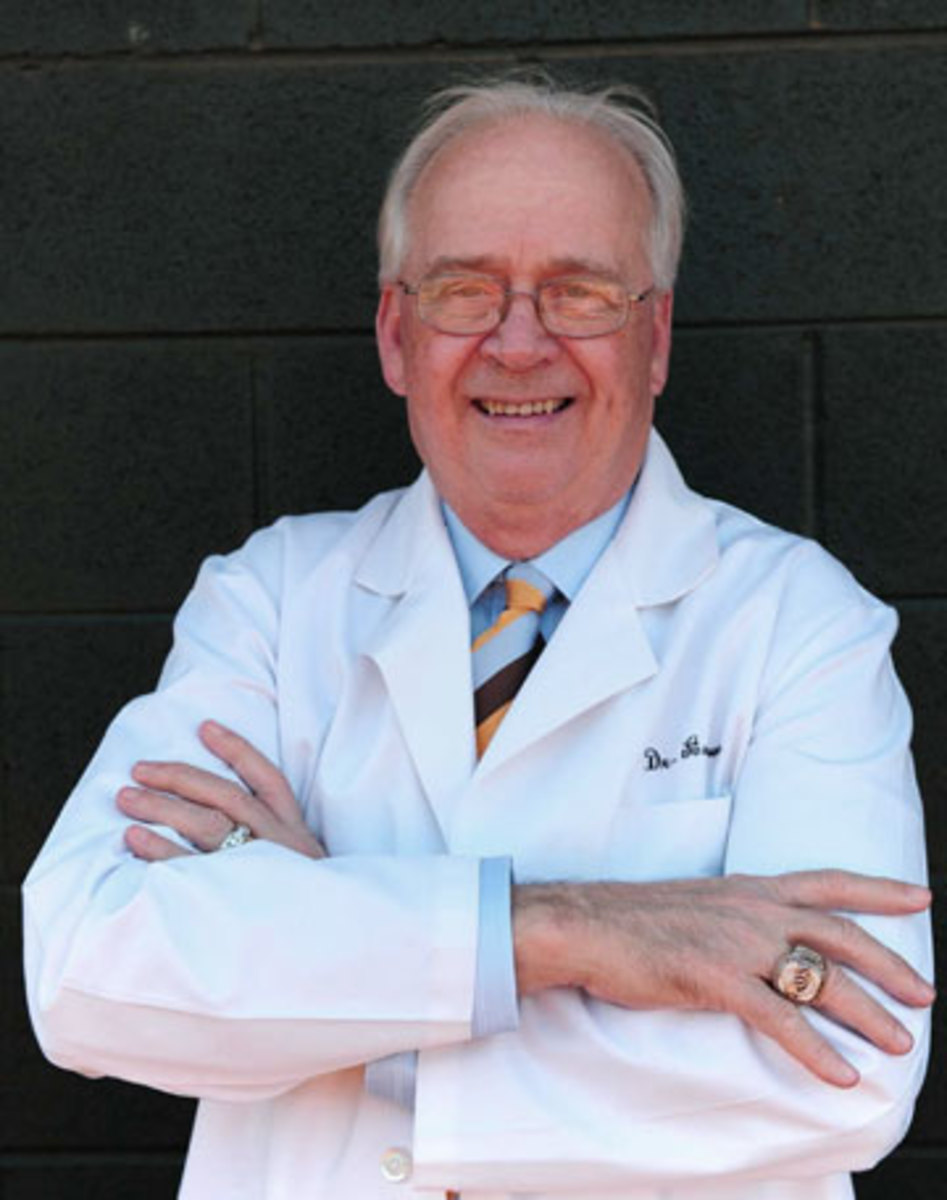

Andrews, a pioneer in sports medicine, and his team are looking toward clinical trials on retired players to better gauge stem cells’ real effects. (Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated)

Chris Johnson was ready to return to the football field when the Jets opened training camp in Cortland, N.Y., last week. He aced his conditioning test—“He was flying,” coach Rex Ryan told reporters—but the team will ease its prized free agent into a full workload. The true test will be how Johnson’s knee holds up weeks, months and years down the road.

Andrews speaks carefully about the potential of stem-cell treatments. He’s hyper-aware of the danger of sensationalizing among his clientele of elite athletes, particularly since many questions remain—not the least of which is how well the treatments actually work. But the early returns have motivated him, as has seeing his top patients go abroad for therapy. “They don’t really know what they are getting,” he says. “Are they getting illegal stuff? We don’t have any control over it, so it’s something we needed to bring back and do in a controlled environment here.”

His team of doctors is working on expanding and optimizing their stem-cell treatment options. Adam Anz, an orthopedic surgeon at the Andrews Institute, has traveled to Malaysia four times to learn from Khay Yong Saw, a surgeon who has had success repairing cartilage defects with the aid of stem cells harvested from the bloodstream. Josh Hackel, the primary care sports medicine physician who treats many of Andrews’ patients with stem cells from their bone marrow, has visited IntelliCell to learn more about its fat-derived stem cell technology. When Andrews’ biologics lab opens, clinical trials could begin on some of these new techniques with permission from the FDA—which Anz says he is close to getting for the cartilage innovation.

Andrews’ team is also actively recruiting retired NFL players for a study on the effectiveness of treating arthritis of the knee with stem cells from the bone marrow or with PRP. A longstanding challenge of proving how well stem-cell treatments work in treating athletes’ injuries is that no athlete with his career on the line wants to risk being randomized into receiving a placebo treatment. Retired players, who would receive the treatment at no cost to them, are the next-best patient population.

The end game? A toolbox of proven biologics treatments, each of which are specific to a certain kind of injury based on the source of stem cells, the amount, when they are administered, etc. “We’ve gotten really good at carpentry,” Anz says, referring to advances in arthroscopic surgery. “The thing we haven’t really been working on is the biologics.”

Here’s why the arthroscope analogy is a good one: That instrument, introduced to the U.S. in the 1960s, changed the outcomes and prognoses for a generation of athletes by making surgeries less traumatic and more precise. But recovery times and outcomes have still depended on the body’s own ability to heal itself. Once cartilage is damaged, for instance, it hasn’t been able to self-repair. And while athletes are restoring their muscles faster than ever following ACL surgery, their return to the game is still limited by how fast the new ligament graft heals and matures inside the knee.

“Instead of taking a year, a year and a half in order to get well, maybe we can cut that down in half,” Andrews says. “We have an old saying: ‘You can’t bargain with Mother Nature.’ The biologics, the stem-cell therapy, is the revelation that may change that."