That ’70s Strike

That ’70s Strike

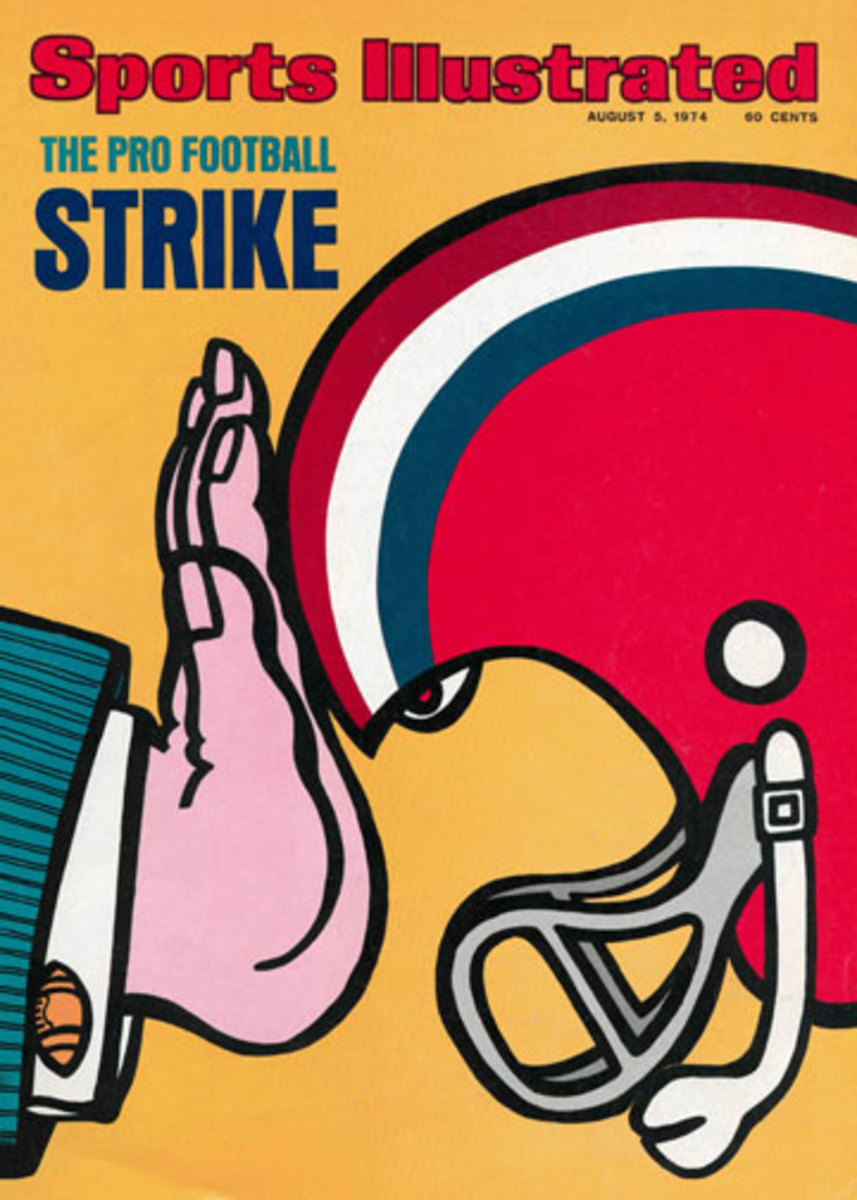

The ’74 Hall of Fame Game between the Bills and Cardinals featured teams of rookies, free agents and nobodies. The game’s best back, fresh off the first 2,000-yard season, was a no-show. (John Iacono/Sports Illustrated)

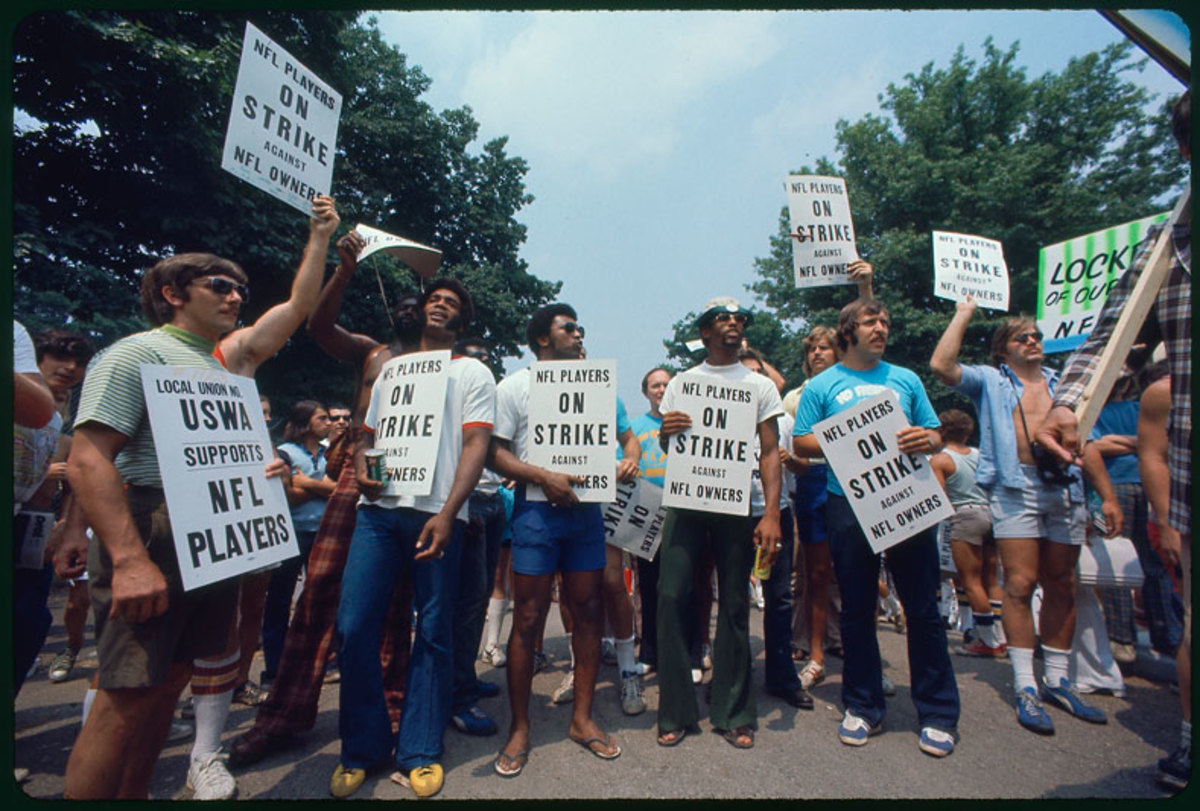

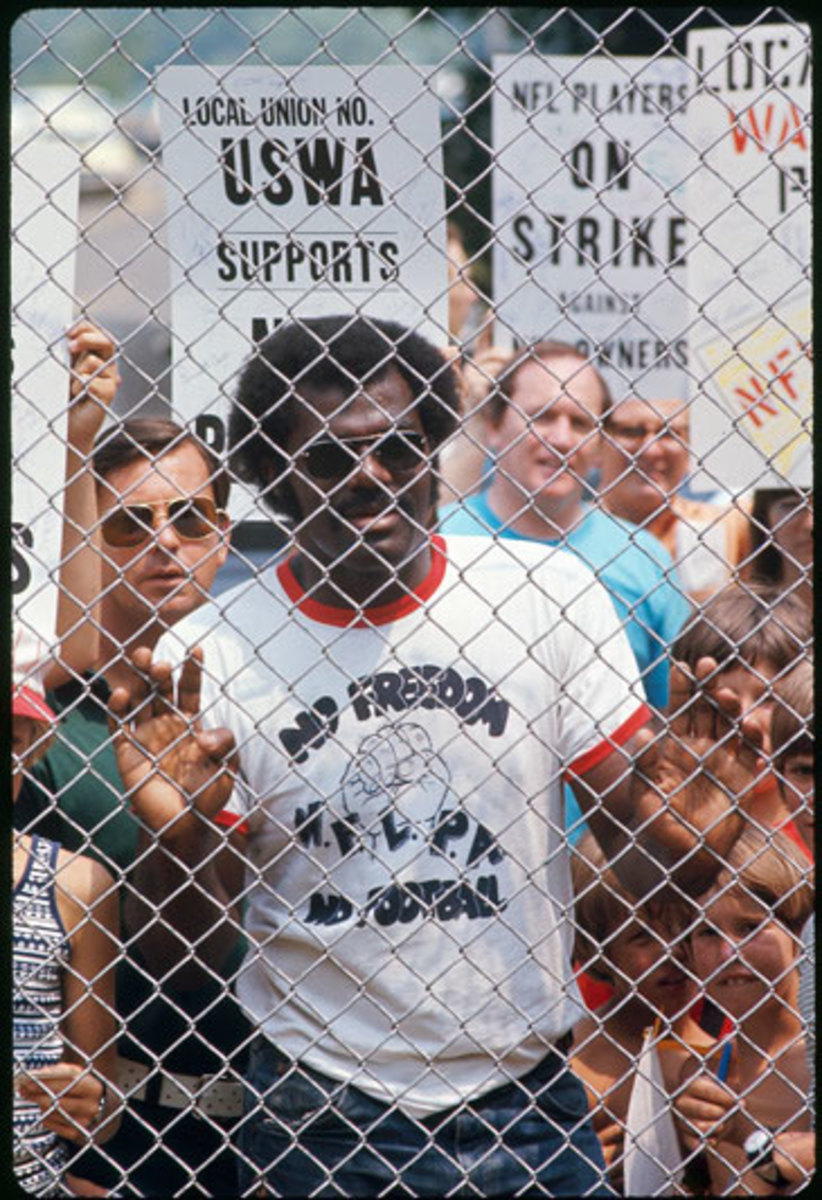

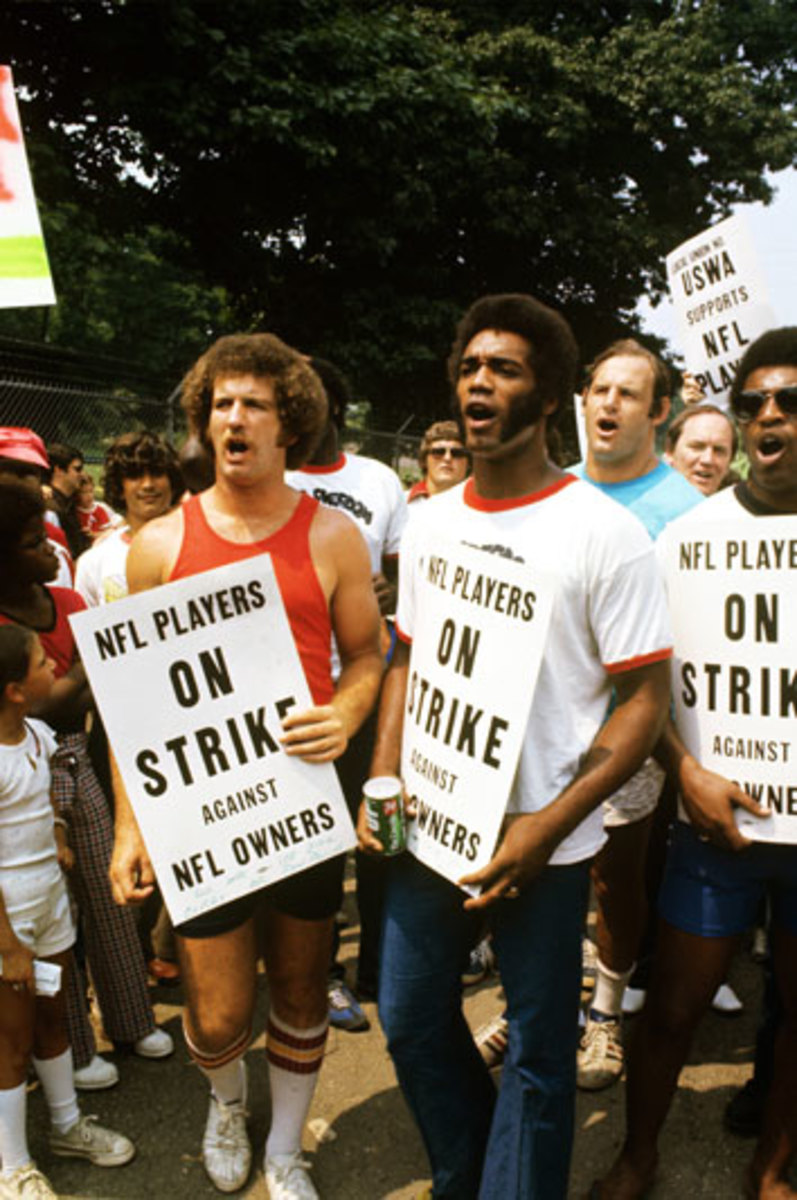

Under the slogan “No Freedom, No Football,“ players were seeking an end to the Rozelle Rule limiting their free agency, among 63 demands. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

Vikings defensive tackle Alan Page, NFLPA president Bill Curry and Oilers quarterback Dan Pastorini were among the striking players. (John Iacono/Sports Illustrated)

One young fan stood in shirtless solidarity. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

Though the players preached unity, several hundred had already crossed the picket lines and joined their teams a month into the strike. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

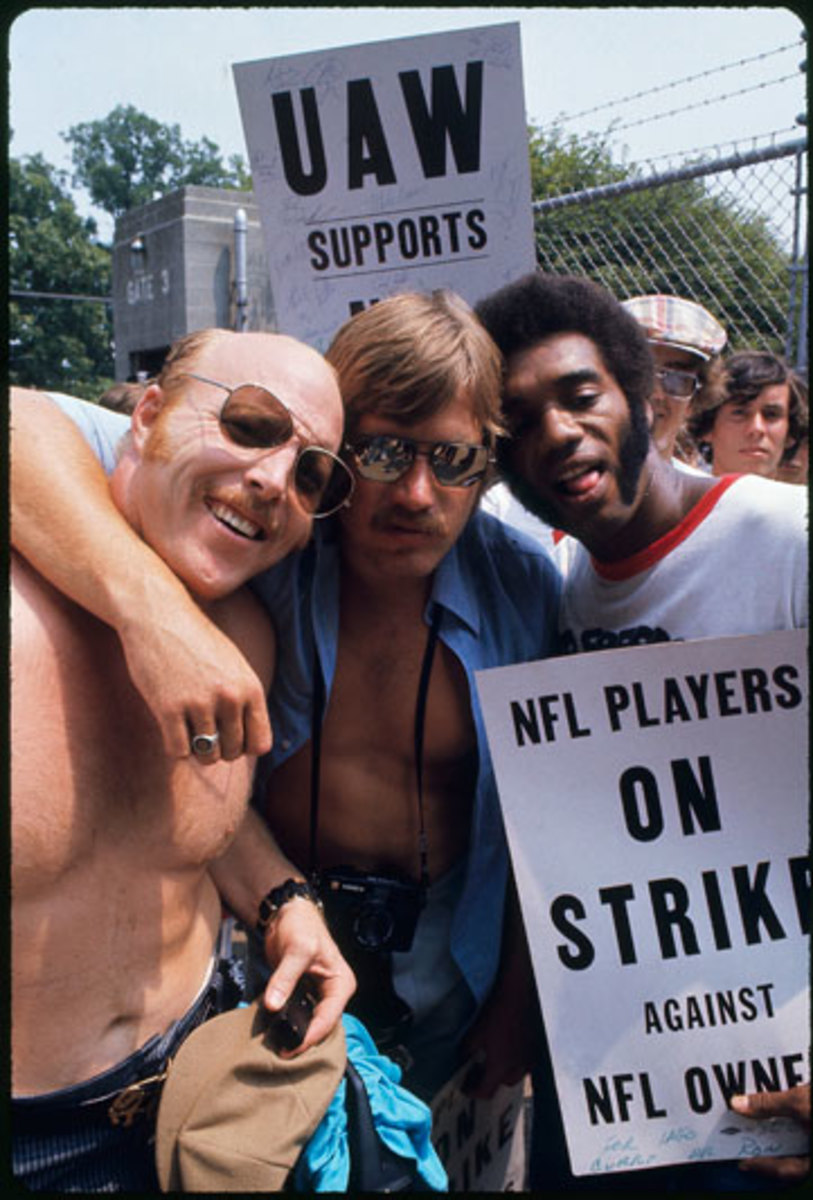

Members of other unions turned up in support of the players. (John Iacono/Sports Illustrated)

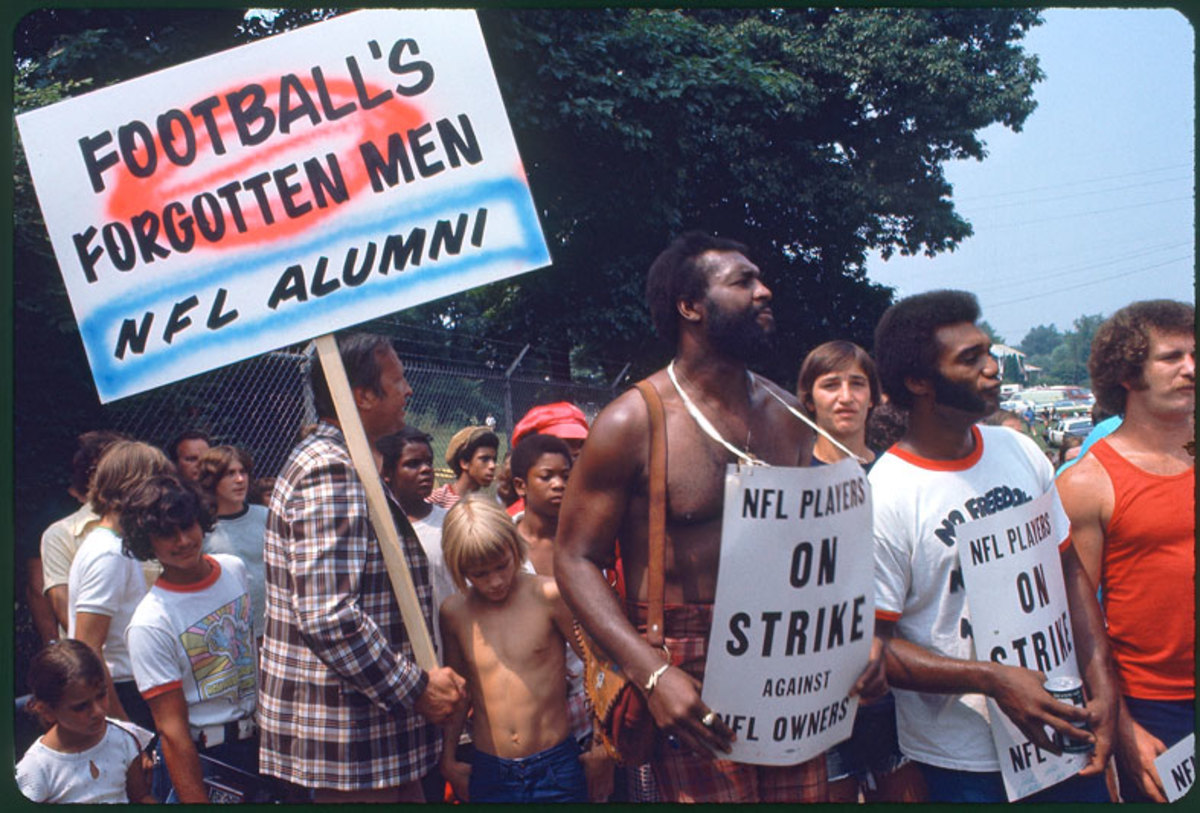

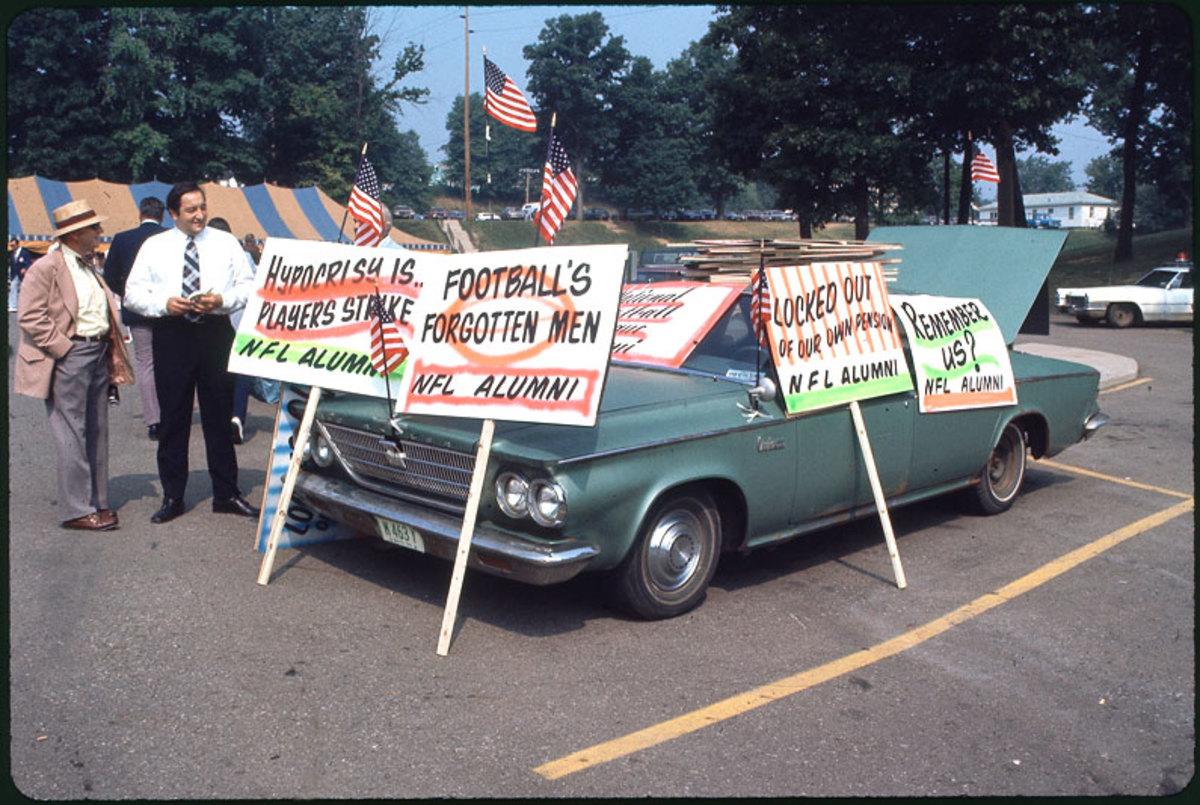

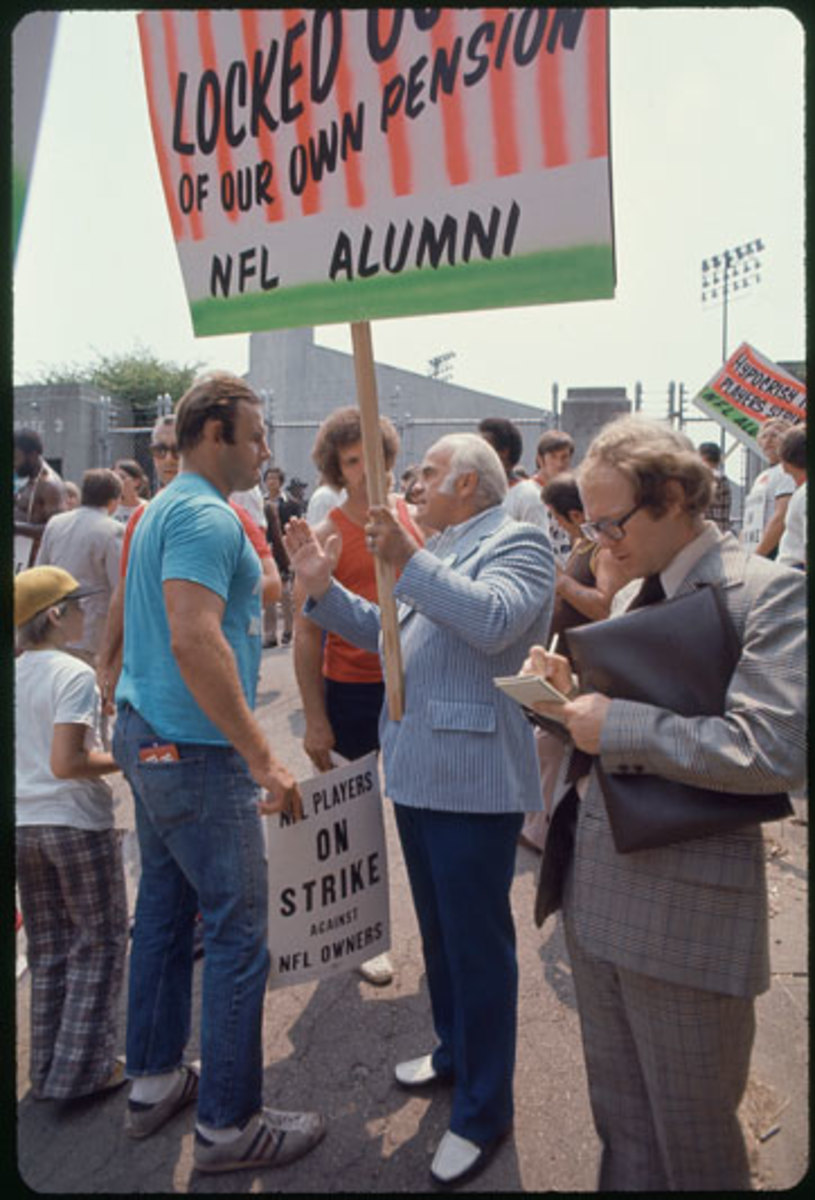

Alumni, however, felt the union was being "led astray" and set up their own pickets. (John Iacono/Sports Illustrated)

“Football’s Forgotten Men”? Many of the issues that day continue to resonate. (John Iacono/Sports Illustrated)

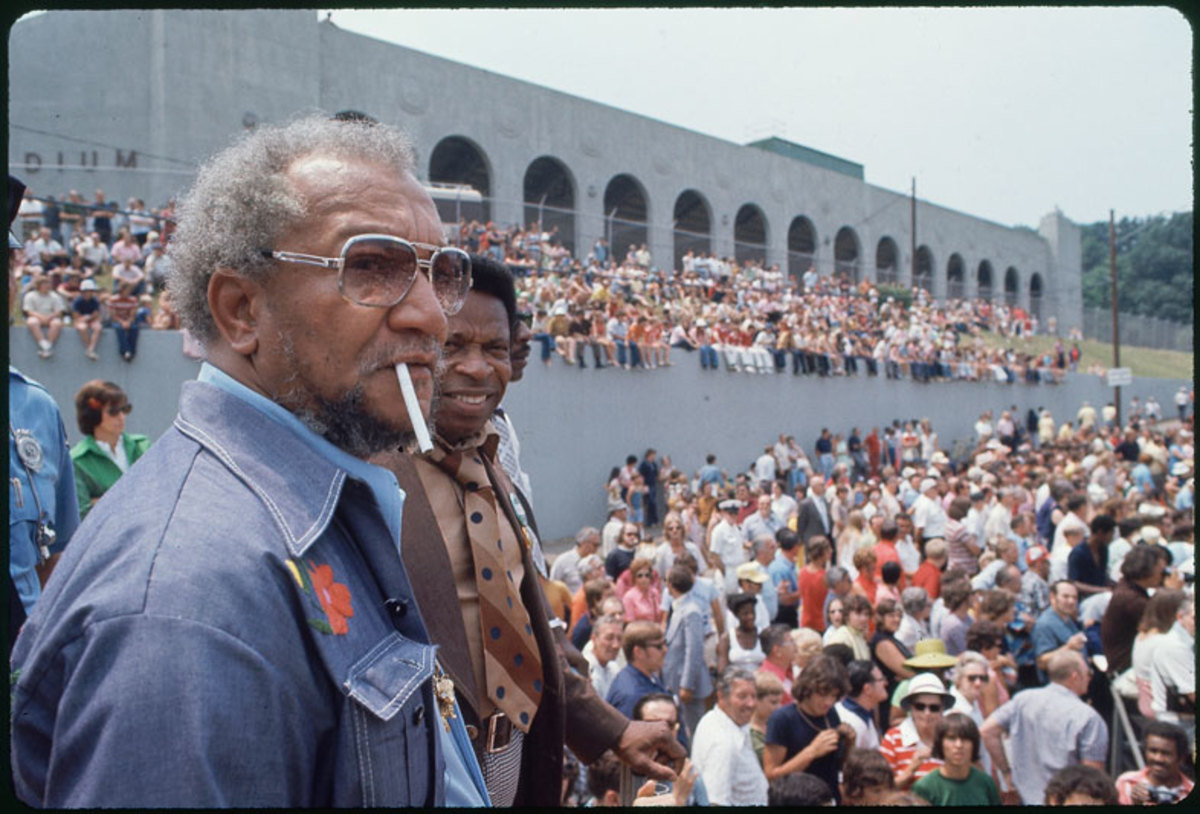

Comedian Redd Foxx was Grand Marshal of the 1974 parade; Night Train Lane, one of that year’s inductees, had served as Foxx's manager. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

A player and an alum debate the issues. (John Iacono/Sports Illustrated)

Despite being played by scrubs, the game attracted more than 17,000 fans. (John Iacono/Sports Illustrated)

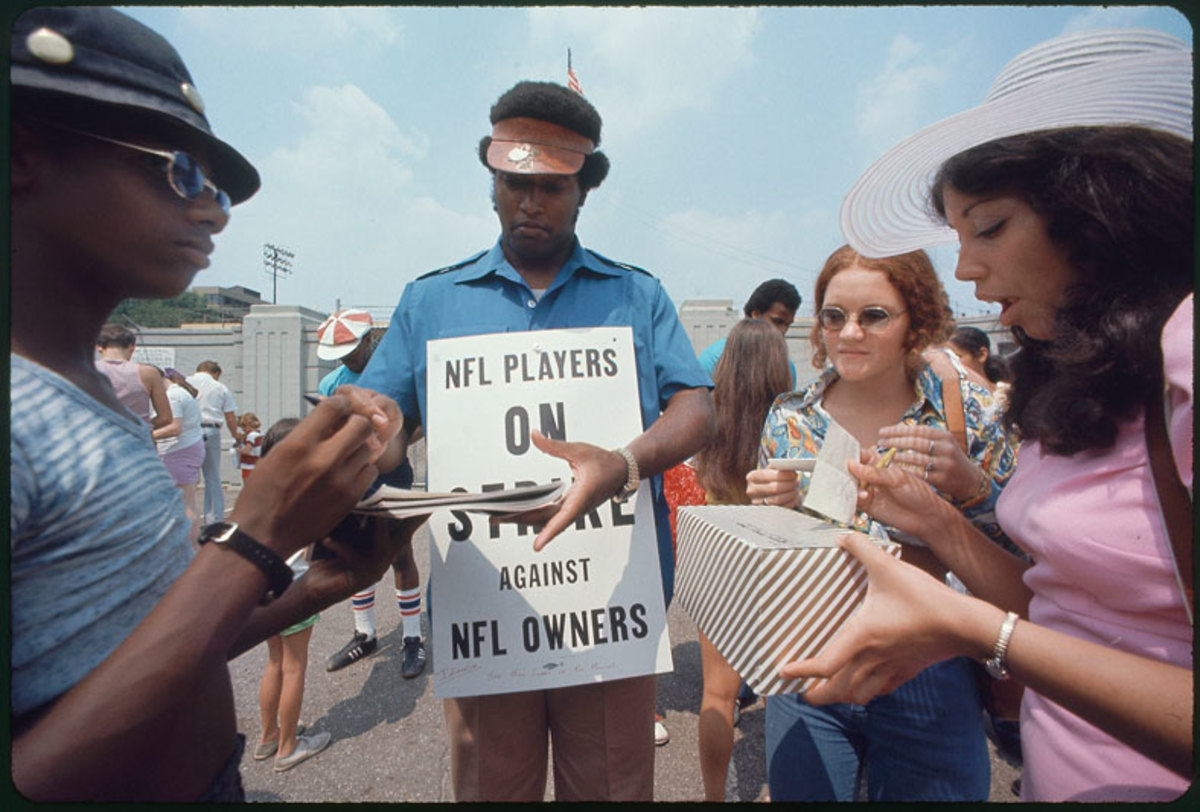

The crowd might not have been fully behind the striking players, but that didn’t mean an autograph was out of the question. (Neil Liefer/Sports Illustrated)

Page, who would be inducted into the Hall himself in 1988, looks on. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

Bystanders and -sitters seemed more bemused than partisan. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

Bills legends, for a day at least. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

For some, it would be their only NFL action. But they made it to Canton! (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

The guys in red beat the guys in white 21–13, but the real losers were the striking players, who returned to work shortly afterward with none of their demands met. It would be nearly two decades before real free agency was achieved. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

Despite the failure of the strike, Roy Jefferson (right), then Washington’s player rep, believes the groundwork was laid for the massive contracts of today. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

It was one of the strangest and most fruitless labor stoppages in pro football history. Locked in a bitter contract dispute with owners, NFL veterans went on strike on July 1, 1974, and did not report to training camps when they opened later that month. “The passion was there,” says then-NFLPA president Bill Curry, who’d played center for the Packers, Colts and Oilers. “But the results … ”

Led by the rallying cry, “No Freedom, No Football,” players wanted the ability to switch teams when their contracts expired. Owners scoffed, saying this would lead to “anarchy.” Today, we call it “free agency.” Among the NFLPA’s 62 other demands were the ability to veto trades and the elimination of the draft. None of that was achieved in the 42-day strike.

The union, led by brazen 34-year-old executive director Ed Garvey, had little leverage (rookies and free agents weren’t governed by the CBA and had already reported to camp) and even less unity. Within a month of the strike’s start, nearly one-fourth of veterans had crossed the picket line. Disenchanted fans sided with owners, and even NFL alumni were irked by the union’s tactics.

It all boiled over at Hall of Fame weekend in late July. As Tony Canadeo, Bill George, Lou Groza and Night Train Lane were to be inducted and the Buffalo Bills were to play the St. Louis Cardinals in the traditional Hall of Fame Game, more than three dozen striking players arrived in Canton to make their case. “We wanted to make sure the NFL understood we were behind this 100 percent,” says wide receiver Roy Jefferson, Washington’s player rep.

“It was almost impossible to articulate to the public or the owners why this was important to us,” Curry says. “So this was our best way to get our message across.”

The method of delivery was a matter of debate among union members. “A few guys said, ‘Well, let’s be careful not to embarrass the Hall of Fame and the inductees; we have to be respectful,’ ” Curry recalls. “Then there were those who said, ‘Let’s go out there, make a statement and beat people up!’ I mean, it was the ’70s after all.”

Curry encouraged his crew to protest peacefully. But they were surprised to find a group of NFL alumni, spearheaded by former Lions end Leon Hart, picketing the picketers. The retired players believed Garvey was leading the NFLPA astray and had left the alumni out of its considerations. (Sound familiar?) The strikers did have local unions on their side—more than 100 members of the United Auto Workers turned out in support. Fearful of disruption, the league’s Management Council spread false stories of where the two teams were staying and when they were scheduled to arrive. The rookies, free agents and unknowns who made up the Bills and Cardinals flew into Canton just three hours before kickoff and were whisked from the airport to a back entrance of the stadium under tight security.

The game went off without a hitch, St. Louis defeating Buffalo 21-13. Perhaps most disheartening for the players, 17,286 fans turned out for the game, only a couple thousand fewer than the previous year. In fact, the most contentious moment of the weekend may have come at the airport after the game, in a dramatic scene between Curry and Vince Lombardi’s widow, Marie. “She storms up to me, stands maybe 50 feet away so everybody can hear, and yells: ‘Bill, what are you doing? Are you crazy? You’re killing me!’ ” says Curry, who was Lombardi’s starting center in Super Bowl I. ‘Now Marie is a saintly figure in football, and a good family friend. I just hugged her and said, ‘I’m sorry Marie. I’ll do better.’ ”

Curry and the striking players returned to work on Aug. 10, none of their demands having been met. It would take two more strikes, in ’82 and ’87—the latter featuring the travesty of “replacement players” in games that counted—and a series of court battles before the players secured liberalized free agency in the ’90s. “I hope that even with the mistakes we made, the things we did lingered with the league and set the groundwork for player rights and mobility,” says Curry, who retired from the NFL in 1975 and coached in the college ranks until 2012.

Adds Jefferson, now 70: “I have absolutely no grudge against players today making so much money. It’s a different game. I get that. But don’t you think if we hadn’t done something back then, if we hadn’t fought for our rights in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, taken it to the picket lines, taken it to court, those guys would have the free agent contracts that they get today? I just hope people recognize that.”