The Franchise Backup

On his last legs, the 34-year-old Michael Vick has embraced the no-pressure role of backup QB with the Jets. (Brad Penner/USA TODAY Sports)

Jets coach Rex Ryan has a favorite Michael Vick story, though telling it makes him cringe. His 2006 Baltimore Ravens defense was perhaps his best ever, but the coordinator barely slept during the week leading up to a November game against the Falcons. Vick was 26 and in the midst of becoming the first NFL quarterback to rush for 1,000 yards in a season. He was in the sweet spot of his prime, still a year away from having his career interrupted by felony charges for his connection to the Bad Newz Kennels dogfighting ring.

Searching for a solution late one night, Ryan designed a blitz to beat Atlanta’s pass protection, but the execution hinged on one defender being wide enough to turn Vick back inside if he took off running. Ryan harped on the player all week: Not wide enough!Run to the numbers! That’s the only way to be sure! Get wider! The Ravens actually did a good job of containing Vick, except for when that specific blitz was called. The crucial defender didn’t run to the numbers—didn’t think he needed to—and Vick blew past him and around the corner for 17 yards, all the way to Baltimore’s 5-yard line.

“Man,” the defender told Ryan on the sideline, “that dude is way faster than I thought.”

“Really,” Ryan replied in his habitual deadpan. “Imagine that.”

I had some great years and played in some great games and went through a lot,” says Vick, the Jets’ backup QB. “Now it’s an opportunity for me to refresh myself and take a step back away from the game.

When Vick signed with the Jets this March, adding another chapter to his comeback story following a 23-month prison sentence and five seasons in Philadelphia, Ryan made sure to relay that story. It was the coach’s way of expressing to his new quarterback why he wanted him on his team. When asked about it recently, Vick flashed a knowing grin and said, “I think that guy ended up getting cut, too.”

But Vick is no longer the transcendent athlete who once drove a generation of defensive coaches to insomnia, nor is he simply a humbled ex-con who sought reclamation in the City of Brotherly Love. With the Jets, he is in his third and perhaps final act, a 34-year-old injury-prone quarterback backing up a 23-year-old who threw nearly twice as many interceptions (21) as touchdowns (12) last season. And even though the 12-year veteran says, “I would be sick if I had to retire tomorrow,” he seems resigned to the fate of no longer being a franchise quarterback.

JETS PREVIEW:It’s Geno Smith’s job to lose

“The last five years I spent in Philly, I had some great years and played in some great games and went through a lot,” Vick says. “Now it’s an opportunity for me to refresh myself and take a step back away from the game.”

He pauses, letting those words sink in.

“I don’t want that. It’s just—I’m kind of relishing the moment that I’m in right now,” he says. “I am not required to have to do a lot. Preserving my body right now is very important to me, and making sure I can make a strong push late in my career in case I am needed.”

No one, of course, really expects that he is the Jets’ quarterback of the long-term future. But if he can’t beat out Geno Smith for a starting job, then what has become of Michael Vick?

* * *

The Franchise Backup

Vick signed with the Jets for one year and $4 million, but the deal came with non-financial provisos, too ... (Julio Cortez/AP)

... including standing by while Geno Smith takes the majority of reps in training camp. (Julio Cortez/AP)

Despite a petition that circulated in an attempt to keep Vick off the college campus of SUNY-Cortland, the 12-year veteran has been a fan favorite at training camp. (Frank Franklin II/AP)

From top to bottom, people within the Jets organization use the same word to describe Vick: quiet. That can be a good trait for a backup quarterback, a role Vick knew he was inheriting when he made the trip north on the Jersey Turnpike to join his new team. Smith, the Jets’ second-round pick in 2013 and their answer to Mark Sanchez, is the starter in every way except for an official announcement having been made by Ryan.

Vick has seemed simultaneously amused and annoyed by all the quarterback competition rhetoric since he arrived at team headquarters in Florham Park, N.J. The worst-kept secret in the NFL has been driven by general manager John Idzik’s beliefs that competition is good and transparency is bad. But the depth chart was plain to see during a July practice in which Vick got zero 11-on-11 reps with the first team. Afterward, a beat reporter asked Vick if a decision had been made already. “Decision about what?” Vick said, chuckling and patting the reporter on the backside as he left the interview tent.

Some Jets coaches have privately expressed disappointment that Vick didn’t show up more hell-bent on winning the starting job.

He might be an injury or an early losing record away from seeing the field, but Vick’s primary 2014 mission is clear. “He’s here to push Geno, to compete with Geno, to make Geno the best quarterback he can be,” offensive coordinator Marty Mornhinweg has said.

Entering free agency, Vick thought he would be a Week 1 starter this season, somewhere. But he ultimately accepted the Jets’ one-year, $4 million offer that came with non-financial terms, too. Reps with the first-team offense during most training camp practices were divided about 4:1 between Smith and Vick, and sometimes none at all for Vick. He’s almost like a one-on-one teacher’s aide for Smith, who is still learning the offense that Mornhinweg ran in Philadelphia for four seasons with Vick. The Jets also want Smith to use his legs more, and Vick has always been the maestro of that skill.

MORE JETS:Rex Ryan’s last stand

No one is intimating that Vick is washed up, which is why some Jets coaches have privately expressed disappointment that Vick didn’t show up more hell-bent on winning the starting job, or at least a little more vested in making Ryan lose sleep again as he agonized over a difficult decision. His physical gifts—firing a mid-range out-route with the mere flick of his left wrist, and bursting with what he claims is still 4.4 speed in the 40—have always looked so effortless that onlookers have trouble discerning any sense of urgency in Vick’s play. Nor does there seem to be any in what Ryan has called Vick’s “cool customer” persona, either.

“I’m at a very good place,” Vick says. “Very relaxed. Things are more laid back right now as far as football, and off the field. No stress, no pressure. Even though, when you play football, there is always some sort of pressure. But at this stage of my career, I’m just trying to refresh and regroup and see where it takes me.”

* * *

The Franchise Backup

The first overall pick in 2001, Vick became the first QB to have a 1,000-yard rushing season, in ’06. (Simon Bruty/SI)

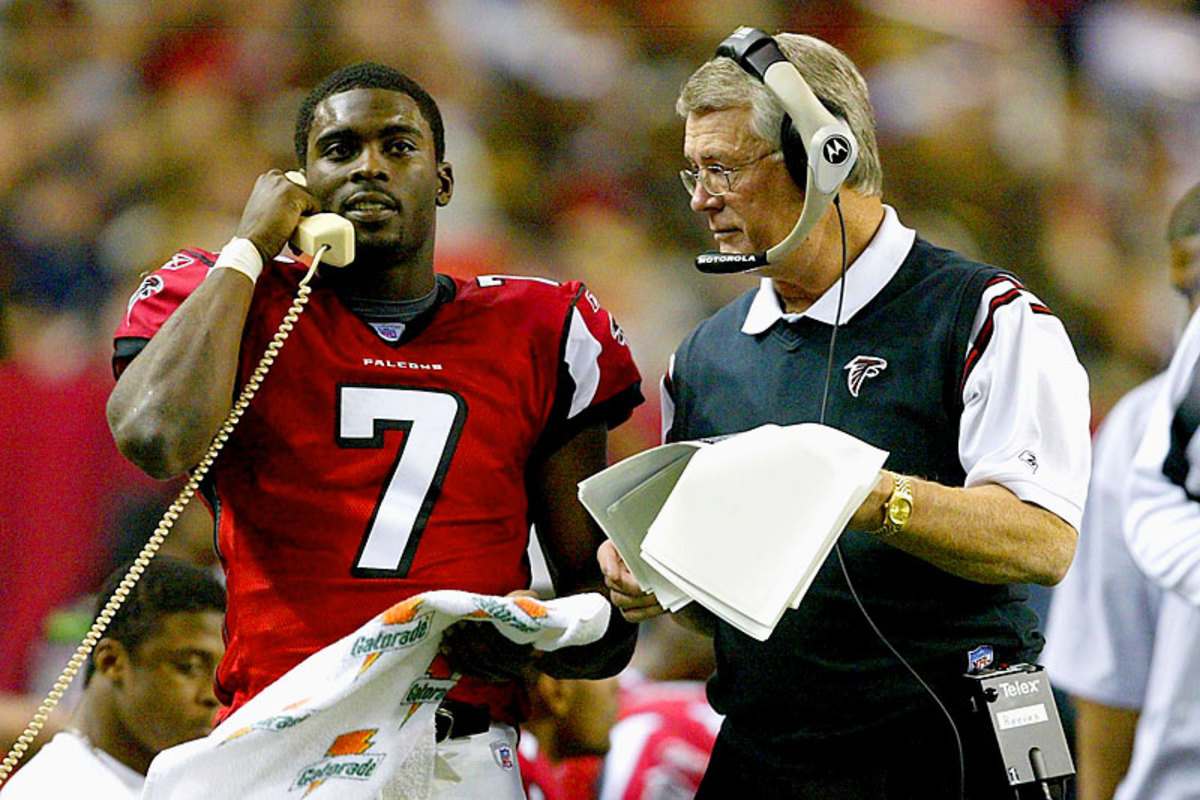

Vick’s first coach, Dan Reeves (r.), says his former QB is “still relying a great deal more on his legs than he needs to.” (Jamie Squire/Getty Images)

During his six seasons in Atlanta, Vick completed just 53.8% of his throws while averaging 643 rushing yards per season. (John Iacono/SI)

In five seasons with Philadelphia, he averaged 400 rushing yards and improved his accuracy as a passer, finishing with a career-high 62.6 completion rate in 2010. (Al Tielemans/SI)

Now with his third team and in a backup role, Vick says, “at this stage of my career, I’m just trying to refresh and regroup and see where it takes me.” (Al Tielemans/SI/The MMQB)

Dan Reeves, the Falcons’ head coach when Vick was drafted No. 1 overall in 2001, understands the career arcs of mobile quarterbacks perhaps better than most. He played with Don Meredith, played with and then coached Roger Staubach, and later coached John Elway. None had Vick’s speed, but they all learned how to run and pass smarter over time.

It’s an education Vick never received.

“He has been in so many different systems now,” says Reeves, who had hoped to make changes to Vick’s game but was fired during the quarterback’s third pro season. By the time Vick was suspended in ’07, he had already been playing for his fourth head coach in Atlanta. “He’s still relying a great deal more on his legs than he needs to,” Reeves says. “He should be at that stage where he feels comfortable and knows when to get rid of the football and not take some of the hits he has to take.”

The sad thing to me is I don’t think he’s ever been able to reach his potential,” Reeves says of Vick. “I think he had that ability, to be one of the best who ever played the position.

That’s always been the knock on Vick, who has played all 16 games in a season only once, in 2006, and who has had only one season in which he completed more than 60% of his passes, in 2010, under Mornhinweg.

“When I look at Mike’s career, the sad thing to me is I don’t think he’s ever been able to reach his potential,” Reeves says. “Whether it was me, or just one coach and one system, he would have had a heck of a career. He’s had a good career, but I think it could have been one of the best. I think he had that ability, to be one of the best who ever played the position.”

It makes you wonder about the up-and-coming generation of franchise quarterbacks, many of them mobile. If they don’t develop true pocket-passing skills, are they destined to become big-name, overpaid backups? Vick missed two seasons during his 548-day imprisonment at a federal penitentiary in Kansas, and he never mastered “old player skills”—the idea, for example, that a young baseball player can break into the majors hitting solely for power but won’t stick around as long as his peers who also learn to hit for average.

Vick has now taken a back seat to Geno Smith, the Jets’ second-round pick in ’13. (AP)

No doubt about it, Vick was still an electric player when he returned to the NFL for the second act of his career. In 2010, his second year back, he battled Tom Brady for player of the year, throwing a career-high 21 touchdowns (in just 12 games) and earning his fourth and final Pro Bowl nod. Vick by nature is a people-pleaser, a guy who can get easily distracted by friends, hangers-on and the demands of stardom. He was at his best, one Eagles source says, early in his comeback when all of that had been stripped away, when all Vick had was a tenuous second chance and few people penetrating his inner circle.

“He proved that year,” then-Eagles coach Andy Reid now says, “that this game is such a microcosm of life.”

When the Eagles took a chance on Vick, team owner Jeffrey Lurie tried to set a new standard by which his quarterback would be measured. “Frankly, the legend of Michael Vick will be determined as we go forward,” Lurie said at press conference announcing the signing in August 2009. “It won’t be determined on the field of football.”

Vick began speaking to thousands of at-risk kids on behalf of the Humane Society, sharing his cautionary tale, and he appeared on Capitol Hill in 2010 to support legislation creating tougher penalties for those who brought children to watch dogfighting. Last summer he helped establish Team Vick Field in the North Philadelphia neighborhood of Hunting Park, his $200,000 donation going a long way toward providing a youth football team its first home field in nearly two decades. “He’s done some things that no quarterback really ever did,” says Lurie, whom the Jets spoke with before signing Vick, “and turned out to be a quality person after having gone through everything that he went through. That’s a good combination.”

The quarterback’s foundation, Team Vick, vows to give “second chances” to those who need it most. Strictly in a football sense, Vick is now on his third.

* * *

The Franchise Backup

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated :: Bob Rosato/Sports Illustrated

Fred Vuich/Sports Illustrated

Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated

Before the Eagles’ playoff loss to the Saints in January, LeSean McCoy and DeSean Jackson were among the players who lingered near Vick’s locker during what turned out to be his last week of practice in Philadelphia. Vick is now a veteran cornerstone in the Jets’ locker room, and he commands respect despite not being in a position to directly help the team win.

Jets rookie Tajh Boyd, a quarterback taken in the sixth round this year, attended Vick’s football camp as a kid growing up in coastal Virginia, where Vick is from, and he sought out Vick’s advice when deciding whether to return for his senior year at Clemson or to declare for the draft. Young players go out of their way to tell Vick that they were always him when they played Madden growing up, and wore his Nike cleats before the shoe line was dropped. The Jets QBs voted Vick as their representative on the team’s 14-man veterans steering committee, which Ryan uses as a sounding board (one decision the committee made was not having joint practices with the Bengals before last week’s preseason game).

Young players go out of their way to tell Vick that they were always him when they played Madden growing up, and wore his Nike cleats before the shoe line was dropped.

Despite his gift of speed, however, Vick still hasn’t been able to fully outrun his past. This spring, a change.org petition collected thousands of signatures in the hopes of barring Vick from SUNY-Cortland, the college campus in central New York where the Jets hold training camp, because of his past connection to dogfighting. But you wouldn’t have known it by watching him interact with fans. “We want Vick!” chanted a small crowd after one practice. He signed autographs for at least 20 minutes, lingering until there were no more to sign.

It’s been five years since he left prison, and Vick wouldn’t be human if he didn’t occasionally consider, Is it over? Will the scrutiny disappear? Will people always be skeptical about the authenticity of my efforts to make amends? Not long ago these questions defined his life.

But now there is just one: Can Michael Vick still play quarterback in the NFL?

It’s a strange sight, watching Geno Smith lead the Jets’ offense in jersey No. 7, the number Vick wore in both Atlanta and Philadelphia. Stranger still, Vick seems genuinely happy to be backing up an unpolished, unproven quarterback whom ESPN analyst Ron Jaworski ranked No. 30 in the league.

“It’s kind of hard sitting on the sideline and watching your team play,” Vick says. “But at the same time, when I look around—I look at the stadium, I look at the crowd, I look at myself and see where I’m at—everything becomes irrelevant. I just appreciate the position that I am in.”