Everything’s There But the Fire

A version of this story appears in the Sept. 22 issue of Sports Illustrated.

EUGENE, Ore. — Marcus Mariota looks as if he’s been designed by a franchise-quarterback computer program. Oregon’s redshirt junior is 6-4 and 219 pounds, runs a sub-4.5 40 and has all the other measurables any NFL team would want, from arm strength to elusiveness to a remarkably quick mind.

He also has a bulletproof work ethic and a desire to be great. Raised in Honolulu, he’s kind and humble and soft-spoken and has never been linked to any sort of off-the-field trouble. At the VIP entrance to a Las Vegas club, he’d more likely hold the door open for someone than use it himself.

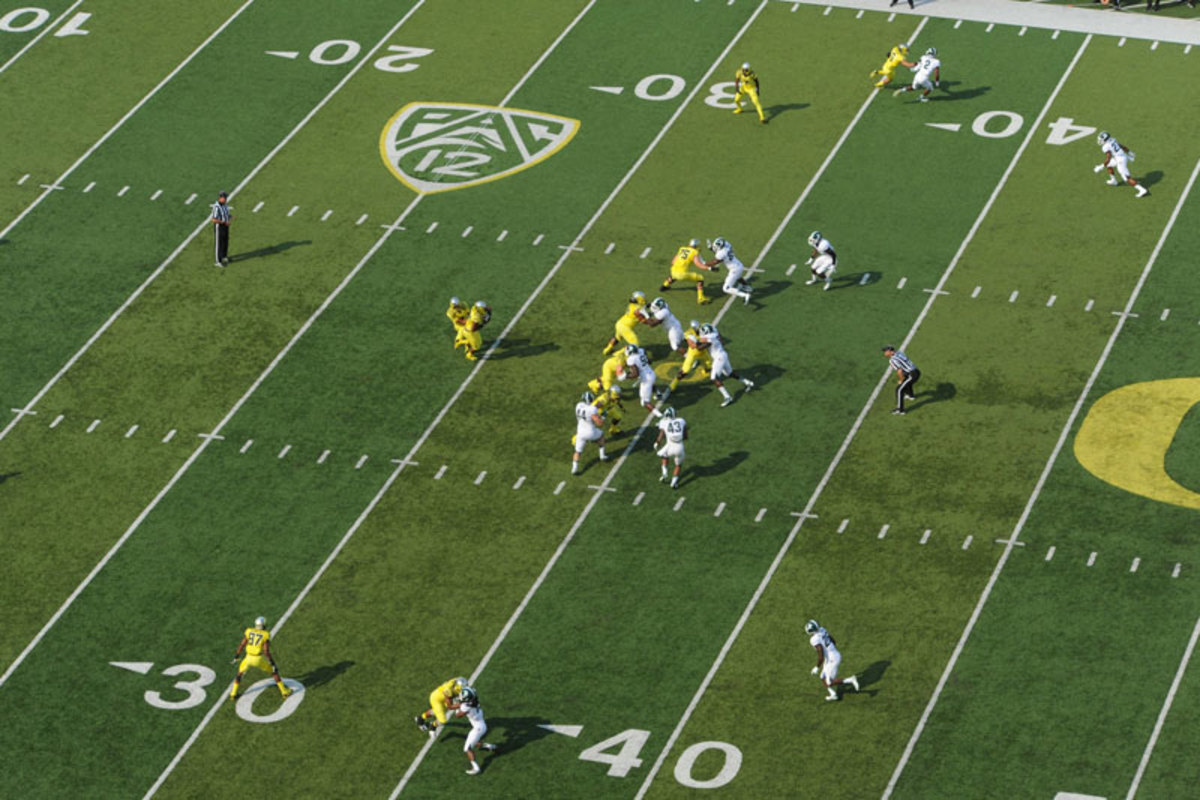

After his 318-yard, three-touchdown, come-from-behind- performance in a 46–27 win over a rugged Michigan State squad on Sept. 6, Mariota is the odds-on favorite to be the No. 1 pick in the 2015 NFL draft, if he leaves school early. (He’ll graduate with a general science degree in December.) But as they do with any prospect, teams will find something to pick apart, and Mariota raises two questions in particular: Can he flourish outside the Ducks’ quarterback-friendly system? And is he . . . too nice? I watched Mariota’s performance at Michigan State—which might be the toughest defense he faces this season—to gauge his NFL potential.

* * *

Through three games this season, Mariota has completed more than 70% of his attempts. (Jonathan Ferrey for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Up close Mariota, who won’t turn 21 until Oct. 30, looks a tad taller than his listed height, and, thanks to the 16 pounds he’s added since arriving at Oregon, he appears wiry strong and plays that way. He rarely goes down on first contact, even against 300-pound linemen, bringing to mind Steelers quarterback Ben Roethlisberger. Against the Spartans, Oregon trailed 27–18 in the third quarter and faced third-and-10. Mariota broke three would-be sacks to escape the pocket, then made an overhand flip to running back Royce Freeman for 17 yards. The Ducks scored five plays later to begin a streak of three consecutive touchdown drives that delivered the victory. (This was also an example of his ability to make clutch plays when the team needs them.)

Mariota throws the ball with a quick, smooth and quiet over-the-top motion. There’s a saying in baseball that a pitcher throws easy cheese—that is, he can bring the heat without taxing his body. Mariota doesn’t have a rocket arm (although he can make all the throws needed), but he generates excellent velocity without exerting much energy. And he doesn’t take a long stride when stepping into his throws, which is the foundation of a quick release.

There simply hasn’t been another guy with Mariota's athleticism who passes the ball as well.

Mariota showed his resolve, accuracy and ability to put a little zip on the ball when, with 10:29 left in the second quarter, the Spartans sent an all-out blitz with seven rushers. He carried through the play-action fake without a hint of stress and then whipped the ball to receiver Devon Allen on his front side before the safety could close the gap. The play went the distance, for a 70-yard touchdown and an 18–7 lead.

Then there’s Mariota’s speed. Even after Michael Vick, Vince Young, Cam Newton, Andrew Luck and Robert Griffin III, Mariota may project as the best dual-threat quarterback ever to come out of college. There simply hasn’t been another guy with his athleticism who passes the ball as well. Mariota reportedly ran a 4.48 40-yard dash at a high school all-star combine, and his 82-yard sprint in Oregon’s 2012 spring game, in which he outran all the defensive backs, is an often retold story.

The best comparison is with Colin Kaepernick of the 49ers. Taken 36th in the 2011 draft, Kaepernick measured 6-5 and 233 pounds at the combine, where he ran 4.53. Similar to Mariota’s role in Oregon’s spread, Kaepernick operated a cutting-edge scheme (Chris Ault’s pistol at Nevada) that’s designed to limit the quarterback’s reads on each play.

At the 2:41 mark of the third quarter, Michigan State’s pass rush broke through the Ducks’ protection on third-and-nine. Mariota escaped to the right and then outran four Spartans defenders to the first-down marker, a sprint of 18 yards after the dropback. Kaepernick is likely the only NFL starter who could have done that.

But that’s where the comparison should end. Mariota is a far more advanced passer. While Kaepernick has a stronger arm, he completed only 58.2% of his passes in college; after a 48–14 win over Wyoming last Saturday, in which he threw for 221 yards and two TDs while running for another 71 and two more scores, Mariota is at 66.2%. (In his first year as a starter, 2012, he connected on 68.5%.) That figure is certainly inflated by Oregon’s scheme, which springs receivers wide open by confusing the defense—five times busted coverages by the Spartans resulted in long gains for Oregon—but quarterbacks are either accurate or they’re not. Mariota has terrific ball placement.

* * *

Everything’s There But the Fire

Mariota faced possibly the toughest defense he’ll see this year when the Ducks hosted the Spartans on Sept. 6. (Jonathan Ferrey for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

At 6-4 and 219, the Hawaii native has the stature for the pros. (Jonathan Ferrey for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Mariota reportedly was clocked at a sub-4.5 40. What’s not in doubt is that he has the speed to outrun most defenders. (Jonathan Ferrey for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

As with all running QBs, Mariota exposes himself to tough hits when he tucks the ball and takes off. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Delivery: More “easy cheese” than cannon. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Though typically quiet, Mariota gets as pumped as anyone in big games. (Jonathan Ferrey for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Mariota’s running shows toughness and elusiveness in equal measure. (Jonathan Ferrey for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Another big plus for pro scouts: A football mind and work ethic that are unquestioned. (Jonathan Ferrey for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

His scrambling style evokes another West Coast QB from an unorthodox system: Colin Kaepernick. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Having developed in Oregon’s spread, Mariota will need some retooling if he’s drafted into a more pro-style system. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Mariota’s savvy play against Michigan State showed he has the ability to run a full-progression-read offense. (Jonathan Ferrey for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

A Pac-12 title—and college football playoff berth—would be a fitting cap to Mariota’s Oregon tenure. (Jonathan Ferrey for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Hard to argue with success. (Rod Mar for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

He’s not perfect, however. Mariota doesn’t have great anticipation on his throws, and he’s not smooth if his primary receiver is covered. Against the Spartans, he missed a wide-open receiver, Keanon Lowe, in the flat for a touchdown with 3:52 remaining in the first quarter because he didn’t anticipate how the coverage would react to the routes.

And for all his accuracy, he hasn’t yet been asked to throw the top-level NFL routes—the skinny post (between two closing defenders in the middle of the field) and the dig, in which a receiver runs 15 to 20 yards down the field and cuts in front of a hard-charging cornerback. The Ducks don’t even practice those routes in warmups because they’re so foreign to the scheme. Mariota will also have to learn to “throw receivers open” against tight coverage, which is to say he’ll have to put the ball in places that only the receivers can get to—the tight back-shoulder throw being one example. That’s a must in the NFL, but it can be learned. So if Mariota is drafted by, say, the Rams, Raiders, Texans, Titans or Cowboys, which use more of a pro-style system, he’s going to need some retraining.

For all his accuracy, Mariota hasn’t yet been asked to throw the top-level routes. It could be argued that Oregon’s offense has stunted his growth.

Of course, many NFL teams are adopting spread-offense principals now, so Mariota may not have a steep learning curve. Either way he should make a much better transition to the NFL than most college quarterbacks. From the looks of things, he can function in any scheme—in fact, it could be argued that Oregon’s offense has stunted Mariota’s growth. With his smarts, accuracy and physical traits, he appears capable of directing a much more complicated system.

The play against Michigan State that really teased Mariota’s potential was the 37-yard touchdown strike to Lowe that gave the Ducks the lead for good at 32–27, near the end of the third quarter. Lowe ran a looping vertical route to the outside from his slot position, and the Spartans had enough defenders to thwart the play. But Mariota looked quickly at the receiver in the middle of the field, which cleared out the safety, then threw a dart to Lowe before he was truly open. That’s graduate-level passing and indicates he is capable of running a full-field-progression NFL offense.

* * *

Mariota’s no firebrand on the field, but numerous top QBs—including Super Bowl winners Eli Manning and Joe Flacco—prefer to lead by example. (Jonathan Ferrey for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

When asked, five high-level NFL executives agreed that Mariota’s laid-back demeanor will be examined closely, though one of them admitted he didn’t think it was a fair question.

Fair or not, it has been asked about Mariota before. A New York Times story reported that when challenged by his coach at Saint Louis School in Honolulu either to be more vocal with his teammates or to run sprints, Mariota chose sprints. When he arrived in Eugene, some of the Ducks’ coaches doubted the quiet kid who took his cues from the upperclassmen could lead the team to great heights.

Outwardly, the concern is understandable. Before Michigan State, the biggest nonconference game in Autzen Stadium history, it wasn’t Mariota who stoked the flames by screaming encouragement at the team; it was senior cornerback Dior Mathis. And as the Spartans scored 20 straight points to take a 27–18 lead, Mariota was seen on the sideline only quietly clapping or giving players fist bumps.

At least one team didn’t see enough of a commanding presence in Teddy Bridgewater to draft him. That’s the landscape Mariota will be wading into.

Entering this season, Mariota admitted that he needed to be more of a leader to push the Ducks to a championship level. After all, they won the Pac-12 title in the three seasons before he took over the starting job. They have been championship-less in Mariota’s two seasons, thanks to back-to-back losses to Stanford.

Some, but certainly not all, NFL teams want a quarterback who will be the unquestioned leader of the team, an alpha male. At least one team didn’t see enough of a commanding persona from Teddy Bridgewater, taken 32nd by the Vikings in May, to consider drafting him. That’s the landscape Mariota will be wading into.

But what players such as Mariota and Bridgewater lack in volubility, they make up for in leading by example. Both players never stop working, and they possess a level-headedness that rubs off on teammates. People around Oregon football have no problem with Mariota’s presence; everyone knows when he’s in a room. Desire can speak louder than words.

Current NFL quarterbacks such as Eli Manning, Joe Flacco, Matt Ryan and Andrew Luck aren’t exactly known for throwing down in the middle of the pregame huddle, but all are bona fide franchise QBs. Manning and Flacco have Super Bowl rings.

Rather than emotion, Mariota will rely on his rare combination of throwing and athletic ability. He’s the next-level prospect whose gifts shout star, even if he speaks in hushed tones.

Selfie with Duck. (Jonathan Ferrey for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)