Why London? And Can It Work?

LONDON — “Welcome to the ninth International Series game,” the British host said, “and that in itself, deserves a round of applause.” He paused, and applause ensued.

This was Saturday night, at London’s Natural History Museum, on the eve of the Raiders-Dolphins game at Wembley Stadium. The NFL was feting the city, in the same way that it usually fetes a Super Bowl host.

Inside the entrance on Cromwell Road, lit up with a projection of the NFL shield, waiters stood at the ready with trays of champagne flutes. A sit-down five-course meal was served, with lamb two ways, corn-fed roast chicken and halibut with a watermelon glaze. British singer Natasha Bedingfield crooned in front of the massive Diplodocus skeleton.

The 240-person guest list included team and league executives, and representatives of many sponsors. Microsoft. Budweiser. Xbox. McDonald’s. Pepsi. Papa John’s, which is growing its international presence. Jeep, which is not a sponsor of the NFL in the U.S., but is one in the U.K. Host Vernon Kay, who anchors an hour-long NFL highlights show on one of the major U.K. networks, read some facts off cue cards written by league staffers.

We have three regular-season games in London for the first time … We have a new opportunity with the early viewing window for the upcoming Falcons-Lions game [which will kick off at 1:30 p.m. London time; 9:30 a.m. Eastern] … We’ve sold out all three games, demonstrating fans’ insatiable appetite for the NFL. Kay looked up after this last line, and scanned the crowd for Mark Waller, the NFL’s executive vice president in charge of the league's international initiatives.

“Corporate speak, Mark,” he said, jokingly.

NFL branding, like this logo displayed on the Natural History Museum, was ubiquitous in London last week. (Jenny Vrentas/The MMQB)

The NFL is selling London. To sponsors. To fans. To the team owners who will ultimately determine how far the league’s stake overseas goes. Since 2007 the NFL has been steadily building its presence in London, and Waller now believes there will be a franchise there in seven to eight years, with home games most likely played at Wembley. Games in London have been successful for the league—all three this year sold out in a few weeks, including about 34,000 three-game ticket packages—but the NFL has been testing, researching and planning with a London-based team in mind.

“The heart of sports fandom is loving a team,” Waller said Sunday afternoon on the Wembley pitch, near a giant inflatable Raiders helmet. “The idea of playing eight games, with 16 different teams, is a really interesting thing at the moment, but I am not sure it is ultimately as compelling as having your own team to root for. It’s probably an easier solution, logistically, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it is a better one.”

The NFL’s international future comes back to one question: Could an NFL team in London really work?

* * *

The NFL banners, spaced neatly between pairs of Union Jacks, were hanging above Regent Street in central London at least a week before the game, announcing the American sports league’s return. On Saturday afternoon the NFL took over this shopping corridor—akin to New York’s Fifth Avenue—between Oxford Circus and Piccadilly Circus, and a crowd reported at more than a half-million filled the streets, decked in NFL gear that represented all 32 teams. Among the jerseys spotted: Tim Tebow. Tony Boselli. Walter Payton and Dan Marino, fan favorites from the 1980s, when Channel 4 in the U.K. launched with a weekly NFL highlights show and Payton’s Bears played a preseason game against the Cowboys at the old Wembley Stadium. When Marino walked out onto a stage on Regent Street mid-Saturday afternoon, the crowd roared, no introduction needed.

Over the past few years the NFL has focused a large part of its international efforts on a marketing and fan-engagement plan in the U.K., to grow the kind of sustainable fanbase centered on London that could support a local franchise. The first International Series game, Giants vs. Dolphins in 2007, tested whether a regular-season game in London could meet the league’s competitive standards. The second game, Chargers vs. Saints in 2008, tested the viability of bringing over a West Coast team for the entire week.

From that point the NFL has worked on building a more permanent presence. There are about 15 league employees in the NFL U.K. office, just off Oxford Circus, which last week hosted meetings with such sponsors as Bose and cordoned off conference rooms for “data capture and social media”—their eyes on the fanbase. There are also two Jaguars team employees who now work out of the London NFL office, since the Jaguars began a four-year stint of London “home games.” The pair run the Union Jax fan club started by NFL UK (22,500 members had signed up by the end of last season) and plan community events. Whether or not the Jaguars consider relocating down the line—Jacksonville owner Shad Khan purchased the London soccer club Fulham F.C. in 2013—their long-term presence serves a purpose.

London Monarchs fans, 1991. Previous failed efforts in Europe make some fans wary of a franchise in the U.K. (John Iacono/Sports Illustrated)

“The concept of the Jags returning is really to test whether, for the new people who are coming into the sport, if you have a returning team, do you become more familiar as a result?” says Alistair Kirkwood, the managing director of NFL UK. “Can existing fans adopt them as their second favorite team, or new fans adopt them as their first team?”

The fanbase in the U.K. is a newer one, averaging around 26 years of age according to NFL UK research, compared to around 45 for the average fan in the U.S. The MMQB surveyed 50 fans on Regent Street on Saturday and at Wembley on Sunday to get a sense of who the NFL’s overseas fans are and what they care about. Thirty of those polled considered themselves fans of one specific NFL team, while the other 20 said they were fans of the league overall. About 60 percent would prefer a collection of games in London featuring different teams, and about 40 percent want a permanent London-based team. Thirty-six of the 50 fans surveyed said they believe there is enough support in the U.K. for a franchise to survive here.

Andrew Kinsman, 49, of Epsom, 15 miles southwest of central London, and Rob Phillips, 47, of Crawley, about 20 miles further south, were debating whether a London team would be successful as they walked around Regent Street on Saturday. The two have been friends since 2000, when they met at Gatwick Airport en route to NFL Europe’s World Bowl in Frankfurt, Germany. (Kinsman was in a Browns jersey, Phillips a Giants shirt.) They discovered that they lived near each other and have been watching the NFL together ever since, along with Kinsman’s sister and Phillips’ wife.

The two have attended all nine International Series games since ’07. But Phillips, who became a Giants fan because he figured a New York team was bound to be good, is longing to root for his own team. A London team. Kinsman is more tentative about the idea, recalling the failed London Monarchs of the World League/NFL Europe. “There would be enough support initially,” Kinsman says, “but if they’re not successful, they may not stay here. I’d rather have some games in London than a franchise that might not work out.”

* * *

The Dolphins landed at 7 a.m. Friday and had a walk-through at the home of rugby club Saracens that afternoon. (Tim Ireland/AP)

The Miami Dolphins landed at Gatwick at 7 a.m. GMT Friday morning, held meetings around 11 a.m. local time, as they would do back in South Florida, then did an afternoon walk-through at the home base of the Saracens rugby club. By 3 p.m. coach Joe Philbin was already looking ahead to an afternoon nap.

The Raiders had arrived five days earlier, on Monday morning, straight from their game against the Patriots in Foxborough, and set up mobile team headquarters at Pennyhill Park Hotel in the town of Bagshot, a base for the England rugby team. Their first practice on the Pennyhill pitch was at noon GMT Wednesday, or 4 a.m. back in Oakland. Many players said they felt like zombies, but they still had four days to adjust.

“If there was a team in London,” defensive tackle Antonio Smith said, “I’m gonna come be on the team in London, so I don’t have to acclimate.”

Through the eight-year history of the International Series, there is no real correlation between when teams arrive, how far they’ve traveled and who wins. Four winning teams have arrived on Monday or Tuesday and stayed the whole week; the other five winners arrived on Friday. In four of the nine games the team that traveled more time zones won, including the 49ers twice.

But if there were a London-based team, the competitive balance would be different. Only the visitors would be making the five- to eight-hour time zone adjustment, depending on where they were coming from in the U.S. Since (under current rules) byes can only come from Week 4 to 12, teams would no longer be guaranteed a bye week on the back end of trips across the Atlantic. And divisional games would have to be played in London, something not permitted under the current international resolution.

Teams scheduled to play in London begin planning their trips in February. How would opponents make preparations for a playoff game in less than a week? The NFL is still working through such complications.

“That’s a competitive issue,” says Cardinals president Michael Bidwill, who used his team’s bye week to observe the operation in London. “Is it a competitive disadvantage to be in a division where you have to travel that many time zones? It’s really the time zone issue; your body clock is way off. We fight it with the three-hour time difference between Arizona and Eastern time. Travel is going to be a factor, and we have to make sure it doesn’t adversely impact the teams that are competing.”

There’s another complication that the NFL has only begun thinking about recently, as the push for London has heated up. Teams scheduled to play in London begin planning for their trips in February. They take two reconnaissance visits overseas in the spring. In August they send a shipment of bulk supplies by boat to save money and space on the team plane. Included in the Raiders’ shipment: 10 cases of 8.5 x 11-inch computer paper for play sheets (standard paper is a different size in the U.K.), a couple hundred cases of Gatorade (teams are superstitious about flavors) and 600 outlet plug converters.

Darren McFadden at a Play 60 event in Surrey. The U.K. fanbase is much younger than that of the U.S. (Lefteris Pitarakis/AP)

If a London-based team earned a home playoff game, how would the opponent make preparations for an overseas trip in less than a week? “We don’t have an answer to that,” Waller says. “We always planned these as regular-season games. So now we are having to work through, how would that work?” Other issues the league is studying include where a London team would hold training camp, and if it would have a base in the U.S. for the offseason program.

The International Series has been a testing ground for the logistics of basing a team abroad. The plan for next season is to again play three games in London, two on back-to-back weeks, to see how Wembley’s pitch, built for soccer, holds up to that wear and tear. The reason: A team based in London would likely play in two- to three-game blocks, home and away, modeled after the University of Hawaii’s football team. Back-to-back games were discussed when the NFL’s International Committee met two weeks ago, along with the possibility of having one team play in both of those games, once as a home team and once as an away team (something that the current resolution and scheduling restrictions might not permit). They also talked about the process for getting volunteers to play “home” games in London.

That hasn’t been a problem yet, but Waller reasons, “The more games you play, the more likely you are to find there aren’t enough teams to volunteer.” Some teams—Kirkwood estimated around a dozen—aren’t able to serve as the home team because of their own stadium leases or other legal considerations. Others are reluctant to give up home-field advantage and a week of gate revenues, though the NFL gives them the average gate revenue they’d receive at their home stadium in the U.S. Wembley gate revenue is typically higher than a U.S. game, given the capacity of the stadium and premium pricing on a par with soccer’s Champions League or F.A. Cup—and the difference gets split among the 32 teams. (The Jaguars, in exchange for their four-year commitment, receive the full Wembley revenue.)

Khan owns London soccer club Fulham as well as the Jaguars. His NFL team gets some breaks thanks to its four-year commitment to the International Series. (Joe Toth/BPI/Icon SMI)

Bidwill’s Cardinals were the host team in Mexico City in 2005 against the 49ers, the first regular-season game played outside the U.S., but that was the season before their new University of Phoenix Stadium opened. He told a forum of U.K. fans on Saturday morning that he’d love to play in London, but, to the chagrin of Waller, only as the visiting team. “The financial consequences to the team,” Bidwill explained to the fans, “could hurt us competitively.”

From the beginning the league has gone out of its way to encourage teams’ participation in and satisfaction with the International Series. It pays for five-star accommodations for 140 traveling members of each franchise and picks up the tab for the international charter, usually a 747 or 777, which has a base cost of $600,000. Responding to feedback from teams, the committee is now discussing some way to compensate teams for the time and effort it takes to plan and pack for an overseas game.

Nine teams are represented on the NFL’s international committee, and only three have not yet hosted or played in London—the Chiefs (Clark Hunt is the chairman), Eagles and Bills—so look for them to be considered for the next cycle. A team like the Vikings that is playing in a temporary stadium could also make sense as a home team in London, although Minnesota just gave up a home game last season to play in the U.K.

An eight-game schedule in London with different teams each week would require eight teams per season surrendering a home game. A team in London, however, would sidestep that issue.

“As long as they get their paychecks,” Bills Hall-of-Famer Andre Reed assured the forum of local fans, “players would play in Alaska.”

* * *

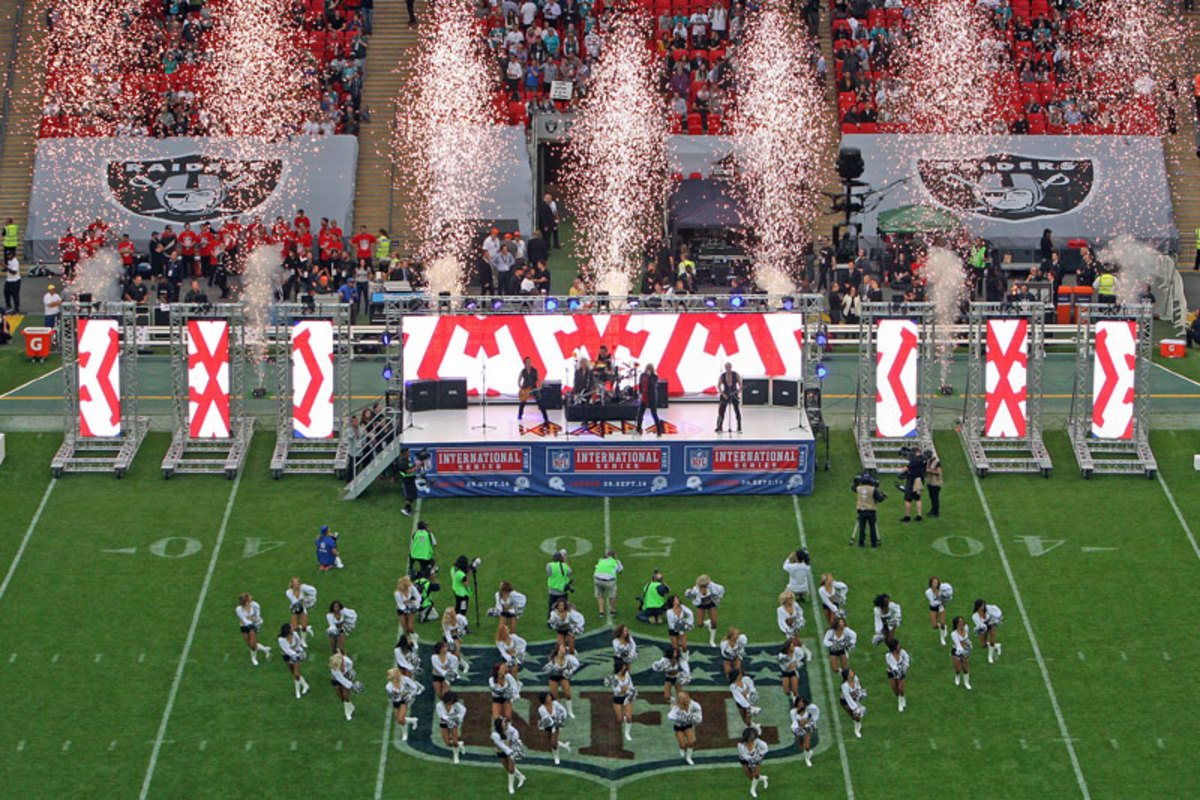

“The spectacle of it all, it’s over the top,“ says one English critic of the NFL who doesn’t go in for cheerleaders, explosions and Def Leppard at his sports events. (Nicky Hayes/NFL UK/Getty Images)

On the eve of Dolphins-Raiders in the U.K., a major football rivalry was being played out in London: Arsenal vs. Tottenham (the “North London derby”). Emirates Stadium, Arsenal’s eight-year old home, springs up out of the densely populated Holloway neighborhood a stone’s throw from the former site of the team’s venerated old ground, Highbury—a reminder that soccer allegiances have deep geographic and familial roots.

Soccer is, of course, the No. 1 sport in the U.K., the standard by which some British fans pooh-pooh our American game. “Don’t take this the wrong way,” says 26-year-old Simon Burgess, an Arsenal fan at Saturday’s game, “but American football seems very … American.”

Asked to explain, he says, “The spectacle of it all. It’s over the top. Thirty, 40 players, each with a specific role. The blazing music. Here, all the noise is from fans. The game is exciting because of the sport.”

Smallwood, at the Arsenal match, sees the growth of American football in the U.K. as a good thing, like MLS in the U.S. ‘And I’d rather watch American football than rugby.’

There is a different momentum to soccer, which doesn't stop and start in between plays. At the Emirates, the scoreboard calmly displays only lineups and an occasional replay, and fans fill the venue with chants and songs passed down for generations. But appreciating this atmosphere doesn’t mean there isn’t space for American football among the 13 million people in the London metropolitan area and, more broadly, in the U.K. sports market, second largest in the world behind the U.S.

Dave Crowhurst, 39, of Dorset in southwest England, attended the Arsenal game Saturday night and the NFL game Sunday. Steve Smallwood, 49, of Eastbourne, on the Channel coast, sees the growth of American football in the U.K. as a good thing, the same way he views the growth of MLS in the U.S. “And,” he offers, “I’d rather watch American football than rugby.”

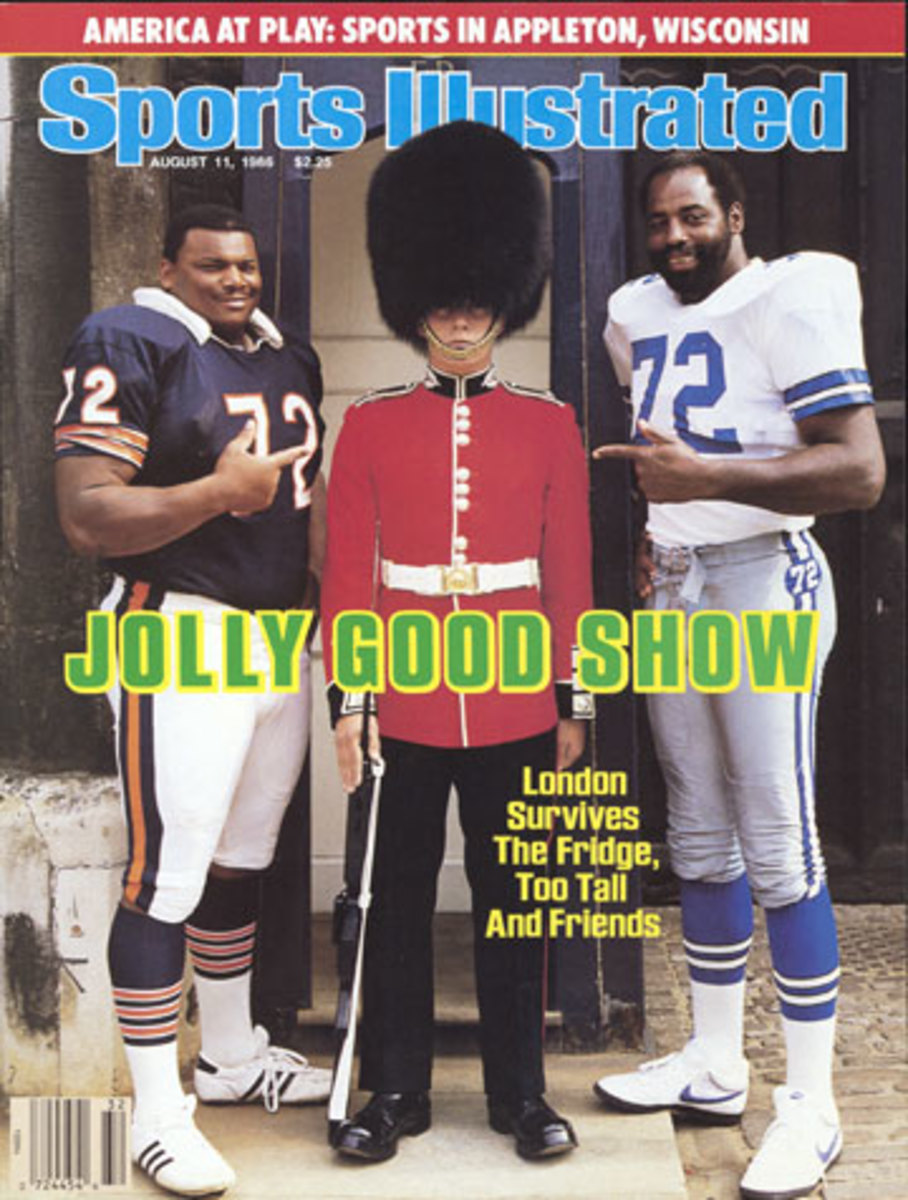

The American Bowl games in London and elsewhere did not necessarily showcase the league at its best. (Ken Regan/Camera 5/Sports Illustrated)

The NFL has looked into establishing a permanent base in conjunction with a Premier League club, but the infrastructure and scheduling restrictions have likely ruled out that option. In addition to Jacksonville’s Khan, two other NFL owners also own soccer teams in England: Tampa Bay’s Joel Glazer (Manchester United) and St. Louis’ Stan Kroenke (Arsenal). “But it’s very tough to see how that would help,” Waller says. Fulham’s stadium seats less than 30,000, and the NFL wants to be in London, not Manchester.

The failure of the American Bowls and NFL Europe came down to the fact that they offered fans a lesser version of the real product—exhibition games or a developmental league. There is evidence now that American football has gained a stronger foothold in the U.K. since the beginning of the International Series in ’07. The NFL has jumped from the 18th to the sixth-most watched sport during football season on Sky Sports, Britain’s subscription sports channel. Last season 13.8 million U.K. viewers watched NFL programming, an increase of 60 percent over the previous year, and the NFL also says more than 12 million people in the U.K. identify themselves as NFL fans. Amateur football participation has grown an average of 15 percent each year since ’07, and there are now 77 university teams playing American football.

In 2012, American football became recognized as an official sport by the British Universities & Colleges Sport organization, the U.K. equivalent of the NCAA. The local instructors for the Play 60 community event in which the Raiders took part on Tuesday, with kids from a local primary school in Surrey, were players from the University of Birmingham Lions, who won the national championship in 2013. “I first saw it on Sky Sports,” said A-Jay Crabbe, 23, a Birmingham defensive back. “It was Eagles-Patriots, and I remember watching Larry Izzo run some special teams stuff for New England. The commentator was talking about how it’s his job to run down the field and tackle the other guy, and I thought, You know what, that’s not a bad way to spend your Sundays. I’ll give that a go. I’m no Larry Izzo, but…”

Some British fans feel more welcomed by the NFL than by big Premier League clubs. Ten members of the DolFan UK fan club were invited to watch the team’s Friday afternoon walk-through; in 2007, when the Dolphins were the host club in London, the fans attended a breakfast with coaches and players and a team reception at the Tower of London. Says one of the club’s leaders, Brian Tennent, from London, “If you lived in Miami, called a Premier League team and said you formed a fan club, they’d say, ‘Yeah, and?’ ”

* * *

Fans of all colors show up for the games in Wembley, but can they be converted into supporters of a single club in London? (Richard Heathcote/Getty Images)

Alan O’Donohoe, 48, from Ashbourne, Ireland, has been to every NFL game played in London since the 1980s. That includes the American Bowl preseason exhibition games, part of a series held in cities around the world from 1986 to 2005. For Raiders-Dolphins, O’Donohoe, a business consultant and 49ers fan, flew in and stayed in a hotel room that he’d booked as soon as he got home after San Francisco’s blowout of Jacksonville last October. Yes, he booked every weekend in September, October and November, until the schedule was announced.

Also at Wembley on Sunday: A group of four friends who drove eight hours from Germany. Two buddies who flew over from Belgium. A family of four that took a seven-hour train ride down from Glasgow.

One appeal of NFL games in London is that they draw fans from all over the U.K. and Europe—just as Saturday’s Arsenal game attracted fans from Beirut and South Africa. But to sustain a team playing a full slate of games in London, the NFL would need a strong base of local fans. According to the league’s research, 88 percent of the fans who attend the International Series are from the U.K., 6 percent are from elsewhere in Europe and 6 percent are American ex-pats or fans who flew in from the U.S. for the game. Of the 88 percent from the U.K., about 60 percent live within a three-hour drive of London.

Of the 50 fans The MMQB surveyed, 41 were from the U.K., and 30 of those fans lived within a three-hour drive. Perhaps most interesting were the stories of how they were drawn to the NFL. Most commonly, it came first through the highlights shown on Channel 4 in the 1980s. (Incidentally, that coincides with the worst period of hooliganism in English soccer. “With the benefit of hindsight,” Waller says, “We probably missed an opportunity there.”)

Fourteen of the 50 surveyed fans said they got into the NFL through friends or family. A few picked it up while on holiday in the U.S.—Miami, typically. Carl Kelly, 28, who is serving in the Royal Air Force, became an NFL fan during tours overseas with American troops in Afghanistan and Qatar.

Several had very specific memories of watching their first NFL game and latching on to a team: Super Bowl XXXV made one a Ravens fan, and Super Bowl XXXVI made another a Rams fan. Chris Perry, 29, from Lincoln, about three hours north of London, recalls falling asleep on the couch as a kid and waking up to see the Packers getting beaten badly. “I did the typical English thing,” he said, “and rooted for the underdog.” Other draws: Fantasy football, Bo Jackson, Colin Kaepernick.

It’s at the point,” says Reynolds, a Sky NFL anchor, noting how accommodating NFL teams have been, “where it almost feels like we are the 33rd market.

Some fans said they couldn’t see themselves abandoning their original allegiances if a team came to London, while others—including the members of DolFan UK—said they’d buy season tickets and back a London team. (Until they played the Dolphins.)

Kirkwood points to how the expansion Panthers carved out a fanbase in the untapped Carolinas when they joined the NFL in 1995. “You’ve got to start somewhere,” he says. “We’d actually probably be aiming more for the people who are still getting into the sport. We are a nation of 60 million, so there’s a lot of people still to work on, to convert.”

Raiders tackle Menelik Watson, a Manchester native, said he spoke to commissioner Roger Goodell at the 2013 draft about being a resource for growing the game in the U.K., and he’s working on organizing offseason camps to introduce local kids to the sport. While the NFL was in London last week, it finalized a new five-year agreement with Sky Sports, which will bring viewers more than 80 live NFL games each season. The International Series games are broadcast on both Sky and the free-to-air Channel 4, which is not done with Premier League games, to maximize viewership.

Neil Reynolds, one of Sky’s NFL anchors, traveled to the training camps of the six teams playing this year in the International Series. Because growing the NFL in the U.K. is important, he said, teams were generous with access to players like Dez Bryant and Matthew Stafford. “It’s at the point,” Reynolds says, “where it almost feels like we are the 33rd market.”

* * *

Cultures clashed in good fun in the stands at Wembley, but sporting differences between U.S. and U.K. run deep. (Lefteris Pitarakis/AP)

On a late September Sunday, Wembley feels like an American football stadium. It’s packed with nearly 84,000 fans who have paid between 17.50 pounds for a kid’s ticket and 440 pounds for a seat in one of the hospitality areas. They arrive several hours early for the NFL’s outdoor tailgate and even stay almost all the way through a blowout 38-14 Dolphins win.

The NFL has looked around but is planning for a future here, in London, and at Wembley. The stadium, which opened in 2007, is unusual in that it has changing rooms double the size typical for a soccer venue and large enough to house a 53-man NFL roster, and after the waterlogged International Series opener in ’07 it upgraded to a hybrid grass-turf Desso surface. As a national stadium (rather than the home of a particular club) it would host about three soccer games between September and December in a typical year, which is relatively easy to schedule around. For Sunday’s game, LED signage encircled the field at ground level, an additional opportunity for sponsors like Pepsi and Gatorade that is not available in the U.S.

This year, however, the celebration in London came at a strange time, with the league and commissioner Roger Goodell under fire for the handling of recent domestic violence cases. Early in the week Raiders players and coaches, none of whom are involved in the current incidents, were greeted by U.K. media with questions about players on other teams and their opinion of the commissioner. Goodell cancelled his attendance at the Saturday morning fan forum and did not travel to London.

Are we just going to be America’s Game?” asks Waller. “The world’s changing, and we are going to have to be more relevant globally.

“His focus has to be on the issues that are most important, and at the moment those issues are in the U.S.,” Waller said. There was no impact on the NFL’s sponsorships in the U.K. from the recent turmoil, he said, but league reps met with each of the sponsors during their visit to London to address the same questions and concerns expressed by sponsors in the U.S.

Growing the business in London, of course, requires the long view. Waller, who grew up in Kenya and Hong Kong and attended boarding school in the U.K., has brought that perspective since he joined the NFL in 2006. In one early meeting, he played the intro to NFL Films’ “America’s Game” series and asked the owners in the room, “Is that it? Are we going to just be America’s Game?”

“Because the world we live in at the moment, that’s probably not enough,” Waller said last week. “The world’s changing, and it’s global, so if we want to continue to be the No. 1 sport in America, we are probably going to have to be more relevant globally. The U.S. is not going to be the center of the world in the next 50 years. It is going to be China or India or Russia or Brazil. If you don’t change the nature of what you do, you are going to go through some very tough times.”

The MMQB This Week

KLEMKO: The Baffling Death of Rob Bironas. FULL STORY

BEDARD: Breaking Down Bridgewater and Bortles. FULL STORY

BENOIT: How to Fix the Pats, and More Tape Analysis FULL STORY

GALLERY: The Ref Who Raced Darren Sproles to the Goal Line. FULL STORY

The owners, ultimately, hold many of the cards for the league’s future in London. The current resolution to play regular-season games in the U.K. runs through the 2016 season, and Waller hopes owners will vote on a new resolution before this one expires. They’ll be asked to consider approving divisional games abroad and London trips without a bye week on the back end. At the moment the league does not favor expansion, so for the NFL eventually to live in London, an owner would have to decide to take his or her team there.

A handful of teams currently have expiring stadium leases—the Raiders, Rams and Chargers. The NFL has also long been trying to crack back into the Los Angeles market, and that alone is a reminder: Just because the league is eyeing something doesn’t mean it will happen.

NFL games in London are still elaborately staged by the league. Shuttles escorted media to team practices during the week, about 70 NFL staffers flew from New York to spend the week abroad, and several Hall of Famers and former Super Bowl champions dotted the festivities. But for London to work, eventually these games will have to start to feel less like an event—or a gimmick—and more like part of the mainstream of the league.

At the end of Sunday’s game, next to the tunnels where players filed off the field to the locker room, one stadium worker sidled up to a line of reporters.

“What’s the purpose of this?” he asked. “Is it a league match? Why is it in London?”

At some point soon, the NFL must hope, no one will be asking that question.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MMwPa1yegHQ&w=560&h=315]