A Rookie All Over Again

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Chris Carr never used to dream about football, but that changed when he stopped playing. After nine years in the NFL, he started having vivid dreams around the time his wife threw him a retirement party in March. And though they were all different, they all centered on the same theme.

In one dream, he was back at Robert McQueen High School in Reno, Nev., loafing in an afternoon practice. “I don’t know if you love football,” his old coach challenged. Carr fired back, “I’ve been playing for 20 years! Put yourself in my shoes!” In another, his college coaches at Boise State were gently telling him he wasn’t going to start at cornerback, but he could still return punts. “But I played in the NFL,” Carr shot back meekly, his ego crushed.

Sigmund Freud would have a field day interpreting these dreams, but they demonstrate what most retired NFL players know: Moving on from the game isn’t just about picking a new path in life.

Carr found new direction rather quickly. He’s a first-year law student at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. His days now revolve around a schedule of five classes: torts, contracts, civil procedure, constitutional law and legal writing.

Knowing that he’ll finally be in one city for an extended period of time—Carr played in Oakland, Tennessee, Baltimore, San Diego and New Orleans—he and his wife, Sarah, did something they’d never done before: they bought a home. Carr hasn’t played football in about 10 months, the longest he’s been away from the game since age 8. He and his former agent, Buddy Baker, last spoke three weeks ago, the longest gap since 2005, when Carr entered the NFL. The transition he’s going through is one that hundreds of players make each year, usually quietly and behind the scenes. Carr allowed The MMQB to follow his journey into life after football, a quest fraught with growing pains and uncertainty for even the most prepared individuals.

* * *

During the mid-August heat of training camps, Carr wandered around the Foggy Bottom area of Washington, D.C., a rookie again. He asked an undergraduate for directions to the law school building, at the intersection of 20th and G Streets. He took a tour of the on-campus gym, during which a cheery student manager asked him if he was a teacher or a student, and wondered if he would be interested in intramural sports? Orientation began a few days later.

“I’m not wondering what camp would be like,” Carr said that day. “There’s a mental relief of being done. There’s always a little stress that’s there. You love football, but it’s always stressful. New year, you want to perform well; a new spot; free agency coming up. This is the first time you take a breath of air.”

Carr walking around the campus of GW, where he’s enrolled in law school. He wanted to be in Washington, D.C., he said, because of the city’s energy. (Jenny Vrentas/The MMQB)

But Carr had an early reminder that the next phase of his life would bring stress of its own. He attended an admitted students’ day in the spring, which included a mock class in an auditorium. The professor presented a sample case, dealing with property, and other students’ hands shot in the air to answer questions. In the NFL, Carr was always known as a smart football player who picked up information quickly. But how would that translate here, he wondered?

Though Carr made roughly $15 million in the NFL, he began planning for a new career more than a year ago. Before going to training camp with the Saints in 2013, Carr wrote a personal statement for law school applications. He solicited letters of recommendation from outside the football realm—his constitutional law professor at Boise State, and one of the partners at the Baltimore law firm where he interned one offseason.

During the Saints’ bye week, he submitted applications to seven law schools. He later narrowed his choices down to three—George Washington, UCLA and Arizona State—but when it came time to decide, he hesitated. He waited as long as he could, until June, to secure his spot at George Washington. He ultimately picked Washington, D.C., he said, because he wants his family to be around the city’s energy. (A portion of his first year’s tuition will be covered by the NFL’s Player Tuition Assistance Plan, which helps players go back to school, contingent on passing grades.)

Carr last played an NFL game on Dec. 15, 2013, a road loss at St. Louis. He was cut two days later, and mentally, he knew he was done. And he meant it: When the Bengals called his agent a few weeks later, inquiring about adding him to their playoff roster, Carr turned down the offer.

As he walks around campus, Carr’s Saints backpack might be the only tell that he once played pro football. He’s 5’ 10”, about 161 pounds, some 25 pounds lighter than his playing weight. He eats about 1,000 fewer calories per day, and he’s abandoned the power lifting that allowed his smaller frame to go up against the NFL’s best receivers.

In August, he posted an ad on Craigslist: Future law student, 31, seeking someone to help me put outfits together. He had only a few T-shirts and shorts that fit his new physique. Excluding game day, Carr points out, “When you play football, you can show up in whatever.” A few days later, he and his new stylist went shopping for a business casual wardrobe, chinos and blazers, all law-school appropriate.

Carr even wrote a farewell letter to the game. It was primarily a thank you note to Rob Ryan, the defensive coordinator who gave him his first opportunity in the NFL, as an undrafted free agent in Oakland, and his last one, in New Orleans last season. Typed, one page, about 700 words, the message was: Thanks for noticing me.

* * *

Sitting in Section 128, in seats he purchased, Carr was able to shout out the Bengals’ tendencies and accurately predict plays. (Jenny Vrentas/The MMQB)

On the opening weekend of the 2014 NFL season, Carr was back in a familiar place. He played three seasons—his best seasons—at M&T Bank Stadium with the Ravens. Before kickoff, as he walked underneath the stadium toward the field, a walk he’d made nearly 50 times before, he paused.

Carr had been given a VIP sideline pass, but wasn’t quite sure if he should fill out the blanks on it. What should he write under “affiliation”? The stadium security guards didn’t even glance at it. When they saw him, they yelped out greetings.

“Just watching,” Carr said a few times, smiling. “Not playing.”

Carr wanted to go to the game for his son, Octavian, who turns 3 this month. He is starting to understand that his dad used to be a football player, but mostly, he just likes watching football—and the blimp that flies over the stadium. On the Sunday morning of the Ravens’ opener against the Bengals, the whole family made the hour-long drive from Arlington, Va.: Chris, Sarah, Octavian, 1-year old Scarlett, and Sarah’s mother, who was in town helping them set up their new home.

Octavian rode on Carr’s shoulders as they walked onto the field during pregame warm-ups. Spotting familiar faces, Carr lit up. Lardarius Webb, a position-mate. Steve Smith, Sr., a fellow player rep for the union. (Both current players complimented Octavian’s curly head of hair). Todd Heap. “Octavian,” Carr told his son, “this is one of the best players in Ravens’ history.” He asked Heap how he is feeling, and they exchanged the knowing glances of two veterans.

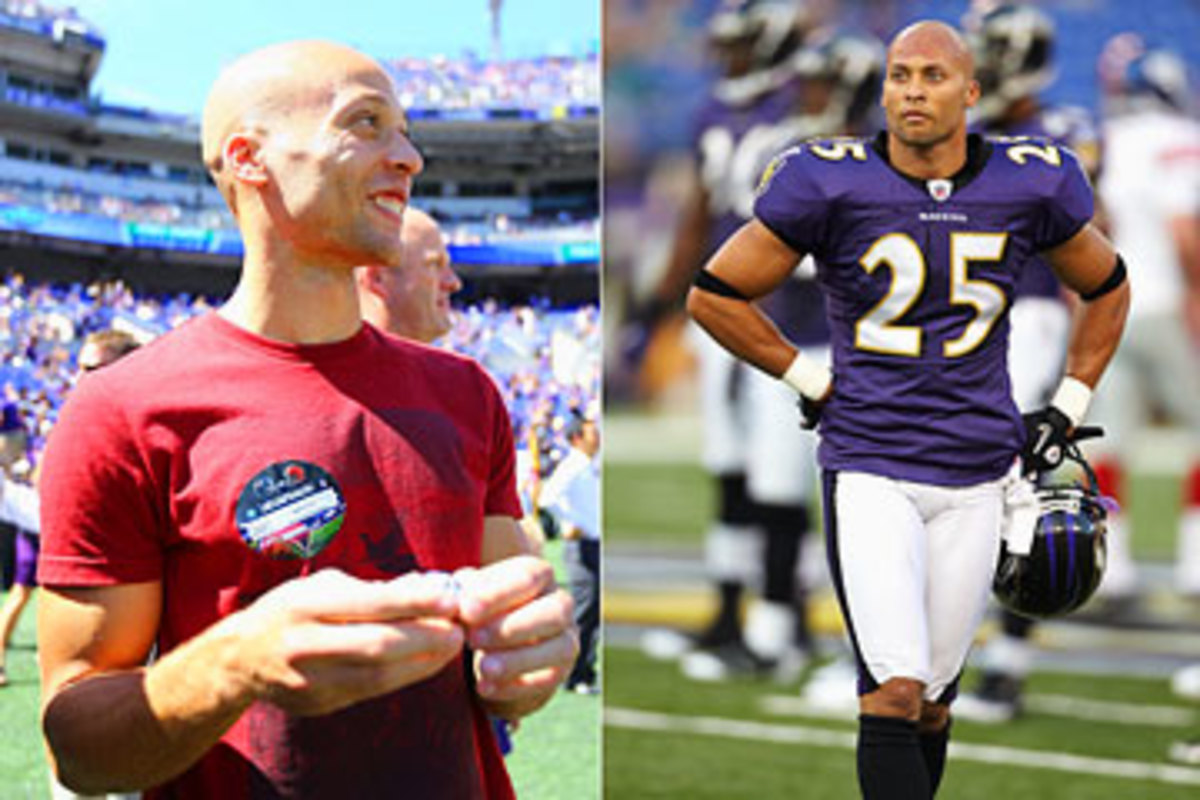

Carr, who stands a mere 5' 10", has dropped nearly 25 pounds from his playing weight since leaving the NFL behind. (Simon Bruty/SI/The MMQB and David Bergman/SI/The MMQB)

Carr’s last year with the Ravens was 2011, which means he missed Super Bowl XLVII by one season. One member of the team’s digital media staff showed him the ring, white gold with diamonds and purple amethyst. Carr wasn’t too bashful to ask, “Can I hold it for a second? Since I never got one.”

This is the part of his NFL career that Carr kept replaying in his mind after he announced his retirement. In newfound downtime, he found himself watching one of the online “Talks at Google” that featured Garry Kasparov. The chess Grandmaster was describing the challenge for humans, once you reach a peak in your career, to maintain the same edge and stave off complacency. Carr’s personal peak came in 2010, when he was a full-time starting cornerback for the Ravens, a goal that once seemed lofty when he entered the NFL as an undrafted free agent.

Carr didn’t slack off after achieving that role, but he wonders how his career arc might’ve been different had he allowed himself to aim even higher, to insist on becoming a perennial starter or a Pro Bowler. But injuries intervened, and nagging back and hamstring issues kept him off the field for all but nine games in 2011. He was caught in a cycle of pushing to get back on the field, returning too soon and missing more time. The following spring, one year into his four-year contract, the Ravens cut him.

“If I would have been healthy, I would have played that year, and I could have finished my career here,” he said. “But you know, it’s kind of cool that I was part of a team that eventually won the Super Bowl. You feel vicariously like you were a part of it, even though you weren’t.”

WHEN THE GAME MOVES ON WITHOUT YOU

Greg A. Bedard on NFL lifer Ken Flajole, a coach who’s watching from home for the first time in nearly four decades. FULL STORY

Those Ravens ties—he and Ray Rice were teammates for three seasons—have prompted questions from his law school classmates in recent weeks. Carr answered carefully, telling them that there’s no one-size-fits-all response. Carr has people in his life who have been victims of abuse, and he believes Rice’s original punishment should have been harsher. But he also believes Rice is the kind of guy who can learn from his mistake and rehabilitate.

Carr is considering writing a story for Nota Bene, the student-run newspaper of George Washington’s law school, and using his unique perspective to examine the way the NFL is governed. The starting point for law students is that laws should be fair, objective and non-arbitrary, something he doesn’t see in the league’s system.

“The NFL needs to have a predictable system to review player conduct, in which you know what is going to happen,” he said. “Even if sometimes you have punishments levied on people that the public doesn’t like, if you are consistent and you are really intent about justice, that’s how you should do it.”

* * *

Carr and Brigance before the Ravens’ season-opener. (Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Carr shook hands with nearly two dozen people on the Ravens’ sideline, but his most meaningful interaction came with O.J. Brigance, the team’s senior advisor to player development, who is confined to a wheelchair because of advanced ALS. When Brigance heard that Carr had just started law school, he had many questions: Where are you living? How many years until you graduate? What kind of law? An aide spoke Brigance’s words out loud, including his final message to Carr: “You make me proud.”

Carr felt a bit of pride, too, taking his family back to a place where he once played. But being there also felt like an out-of-body experience. As a player, walking out of the tunnel and running onto the field was one of the best feelings in the game. On this day, he paused before making the same walk as the memories rushed back. “Going out there, you still have those feelings, and it will never go away,” says Carr, who at one point heard his name being yelled from the stands. Incredulous, he asked a girl wearing a No. 82 Torrey Smith jersey, “You want my autograph?” He signed her game program.

Carr, who last played in Baltimore in 2011, was shocked that fans still asked for his autograph. (Simon Bruty/SI/The MMQB)

Sitting in Section 128, in seats he purchased, Carr couldn’t just watch the game. He analyzed each play as if he were still on the field. On one early drive in the red zone, the Bengals lined up in a 3 x 1 formation, out of which they had run a bubble screen earlier in the game. “Quarterback draw!” Carr called out, right before Andy Dalton took the snap and was stuffed for no gain on a quarterback draw. “That’s a tendency in the red zone,” he told Sarah, realizing as he spoke that he still remembers teams’ tendencies.

Carr didn’t stick around to see the Bengals pull off a 23-16 win. They left early because Scarlett needed a nap. And that game has been the only one Carr has watched this season. On the most recent football Sunday, he went to church with his family, around the time players were heading to the stadium; he had a study group at his house, around the time the early games kicked off; and he was at the law library turning in a legal writing paper while the Patriots were making a statement against the Bengals on Sunday Night Football.

He has distance from the game, but his subconscious is always trying to bring him back to it. There’s another dream Carr remembers. In this one, he was in two places at once: on the field, playing in an NFL game, and at home, watching himself on TV. The commentators on the broadcast were talking about him. “Carr had such a great game,” they said. And that’s when Carr woke up, blanketed in an old familiar feeling: the endorphin rush of having just played a spectacular game.

“Being away for 10 months, it feels a lot longer than 10 months,” he says. “It feels weird. I feel so removed. Kind of like when you think about high school. You have memories, but it doesn’t feel tangible anymore.”

But, he adds, “Those dreams are a reminder. It was a major part of your life. It was your life.”

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]