Joe Greene, and the Three Who Aren’t There

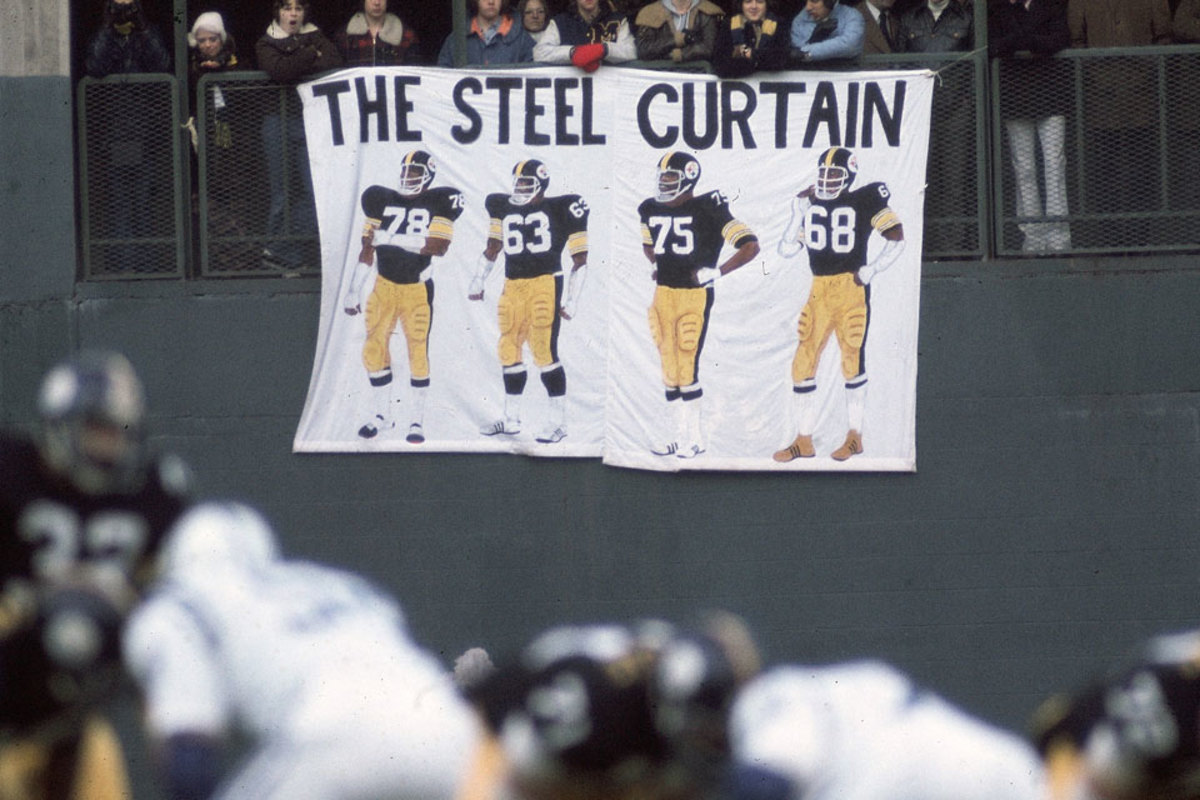

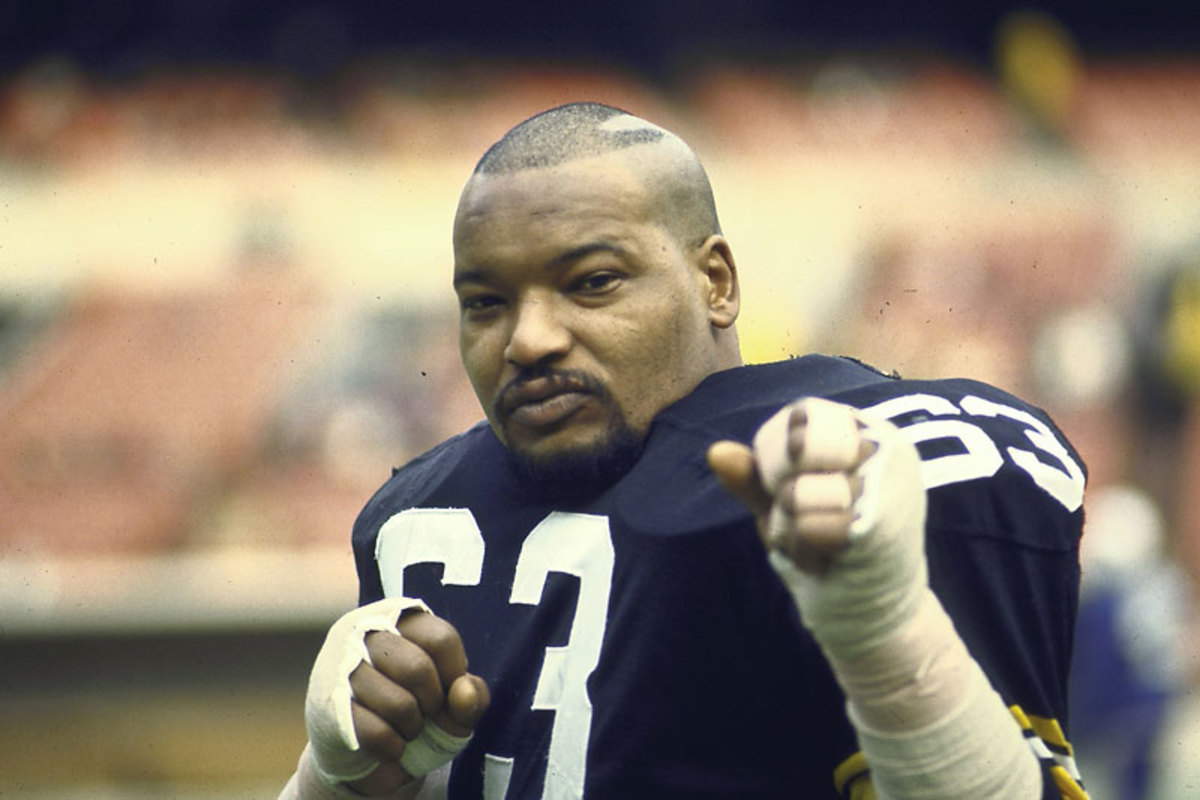

The ’70s: Banner years in Pittsburgh. (Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated)

By Gary M. Pomerantz

From Their Life’s Work, by Gary M. Pomerantz. Copyright © 2013 by Gary M. Pomerantz. Published by Simon & Schuster, Inc., and reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. Follow on Twitter @GaryMPomerantz and on Facebook.

The members of the Steel Curtain front four got another chance to be together more than a decade after they’d broken up. They joined forces in the early 1990s on the card show/sports memorabilia circuit, signing autographs and posing for photos with fans, each man sometimes earning $10,000 or more for appearing. Individually their names still carried strong recognition, but together as the famed Pittsburgh Steelers’ Steel Curtain, they drew even bigger crowds.

Mean Joe Greene, Ernie Holmes, Dwight White and L.C. Greenwood met several times each year at signings in convention centers and hotel ballrooms in Colorado, Florida, Virginia, Chicago, Cleveland, Edison, N.J., Los Angeles, San Diego. They shared breakfasts and dinners in each city, and there was joy in being together again, telling old stories and old jokes, and in watching Fats Holmes eat, as Greenwood said, “a steak, two steaks, and then everything on the table.” Once he became ordained as a minister in 2006, Holmes prayed for the group at each meal they shared. “I’m gonna pray for you, Greene,” he said. “You go ahead and pray for me then, Ernie,” Greene answered. They talked about their kids, Greene talked about his NFL coaching and scouting, Holmes talked about Jesus, and in his hotel room he worked on his sermons. White discussed the business at hand, their group signings. White had good business sense, and an ability to pull the four together. He discussed future possibilities for the group, money to be earned.

They assumed their old roles, and inevitably old tensions cropped up, usually between Greene and Holmes. “Ernie was just different people,” Greenwood said. “Joe was always trying to get things right, as they should be. Ernie didn’t want to listen. And Dwight would say, ‘Screw it,’ and get out of there.”

* * *

Available now in paperback. Click image to purchase.

The lives of Mean Joe, Mad Dog and Hollywood Bags had been relatively straight lines: Greene as a football lifer as Steelers assistant coach and scout; White in the investment business in Pittsburgh and actively involved in his city’s philanthropic life (he and his wife Karen helped raise more than $36 million as co-chairs of a capital campaign for the August Wilson Center for African-American Culture in Pittsburgh); and Greenwood running an electrical supplies business with a storefront set up in nearby Carnegie.

“I happen to think that the ultimate test is not to play football, but to be something after football,” White said. “It’s a real challenge to wipe out that image, that stereotype.” Perhaps because he had managed to do this successfully White added, “I’m more impressed with Wall Street than Three Rivers Stadium.”

Holmes’ life continued to be as colorful and dramatic as his NFL career. He was traded to Tampa Bay for two lowly draft picks before the 1978 season, Noll explaining, “Ernie is very much like Pittsburgh—much better than its reputation,” and then, in short order, his football career was at an end. For a time he lived out west in California. He became a wrestler and shaved his hair again into the shape of an arrowhead. He made an appearance in Wrestlemania 2. He worked as a bodyguard; when the Rev. Jesse Jackson came to Jasper, Texas, in the summer of 1998 to officiate the funeral of James Byrd, a black man dragged to his death along an asphalt road from the back of a pickup truck by three white men, Holmes, seemingly as immovable as a mountain, stood beside the Rev. Jackson. Holmes also became a bit actor, seen in an episode of television’s The A Team and on the big screen as a bouncer in the horror movie Fright Night. In that film a vampire grabs Holmes by the neck and throws him across the floor, a scene that, back in Texas, reportedly made his ex-wife cheer. Near his small East Texas ranch in Wiergate, he opened a nightclub known locally as The Yellow Banana. His club was little more than a roadside shack with thin walls, a strobe-lit dance floor and lengthy bar, and painted bright yellow on the outside; ergo, The Yellow Banana.

Later Holmes became a 688-pound Baptist minister. “That’s what he told me on the phone,” Greenwood said. “He said he weighed ‘Six-Eight-Eight.’” Greenwood didn’t believe it until he saw Holmes. Fats developed troubles with his legs, had a knee replaced, and walked with a cane. Later, he told Greene, he lost two-hundred-fifty pounds, the majority of that after gastric bypass surgery.

“It shocked me, too,” Roderick “Byron” Holmes said when he learned that Ernie Holmes, his father, was becoming a minister. Byron Holmes earned a doctorate as a mathematician, and became an assistant professor of Mathematical Sciences at Texas Southern, his father’s alma mater. Raised by his mother (Holmes’ first wife), Byron Holmes likened his father’s complexity to that of the late rapper Tupac Shakur: “It’s like Biggie [Smalls] said in the movie Notorious, ‘You ask 10 people about Tupac and you get 10 different answers.’ ” Ernie Holmes was like that, his son said. “He had his crazy moments,” Byron said with a laugh. “But that same zeal he had toward football he showed toward the church. He talked about Jesus all the time.”

* * *

Joe Greene, and the Three Who Aren’t There

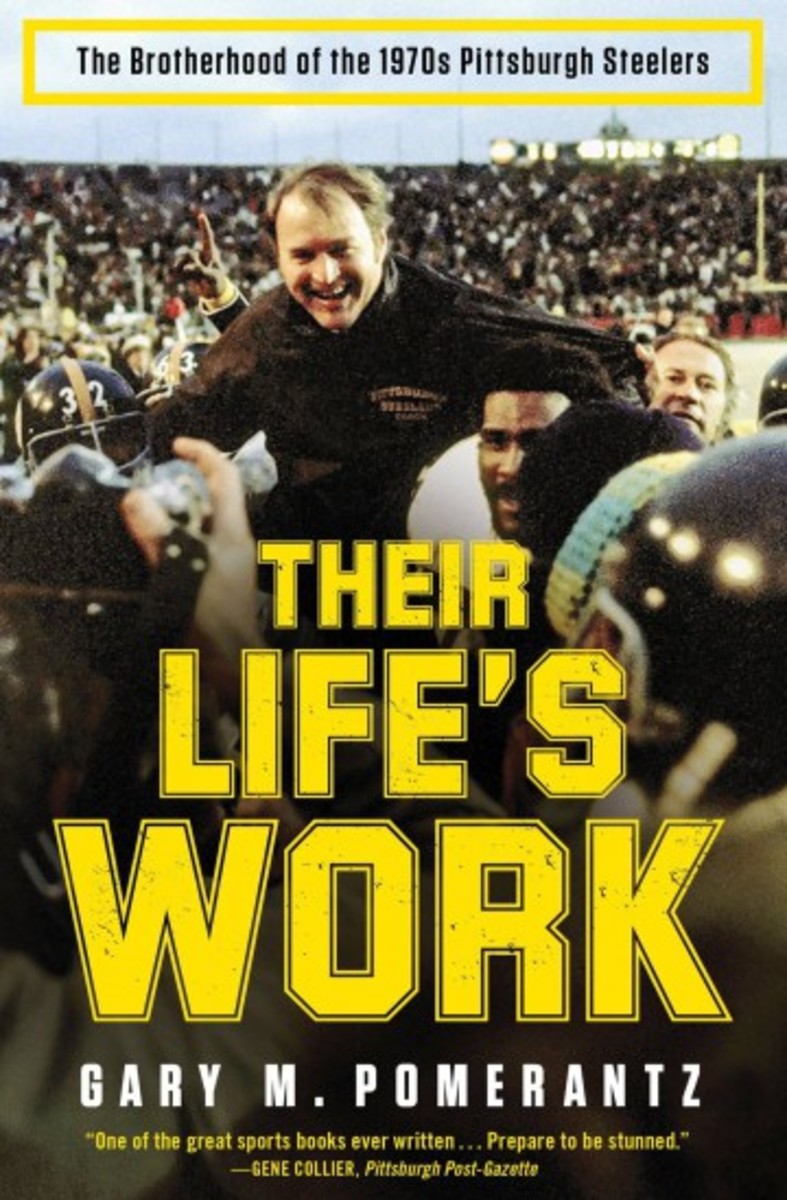

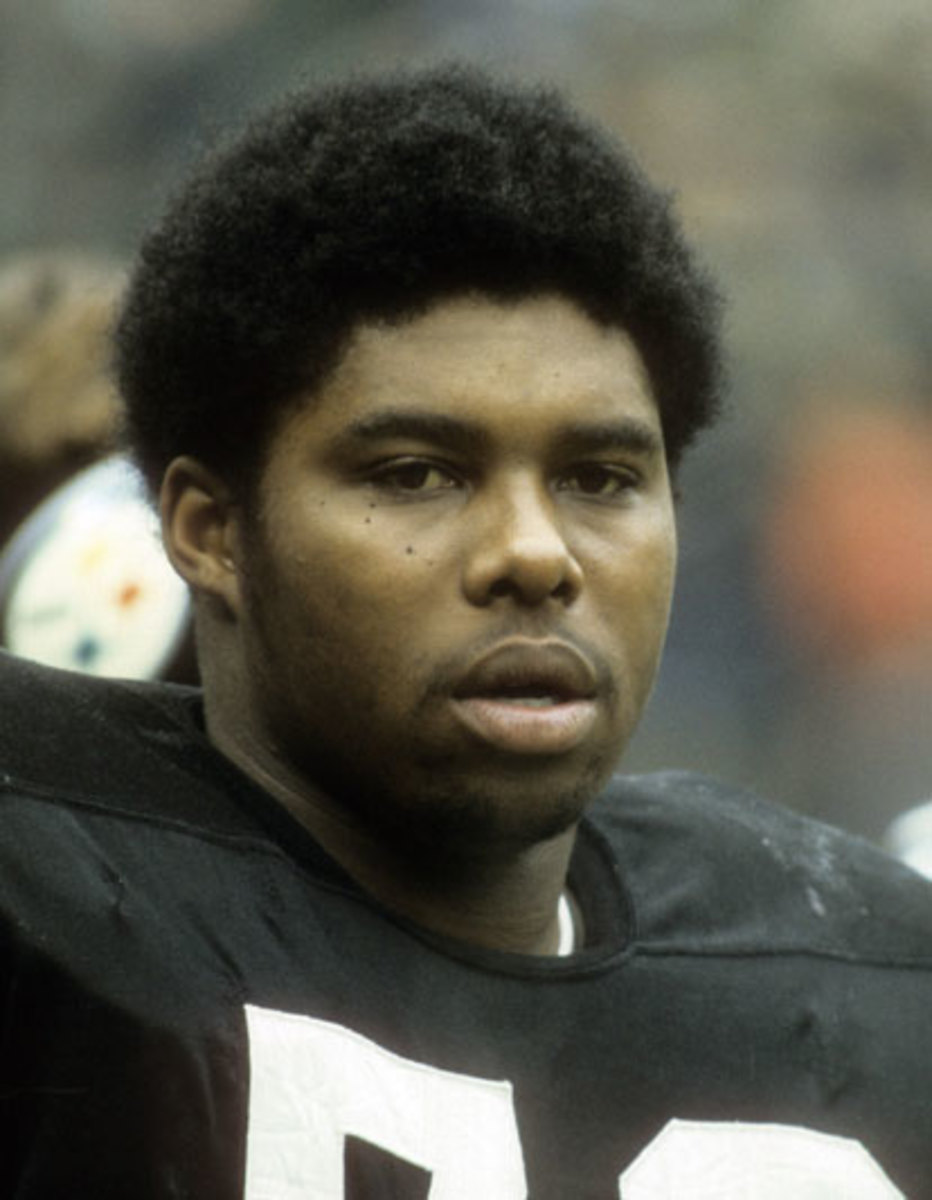

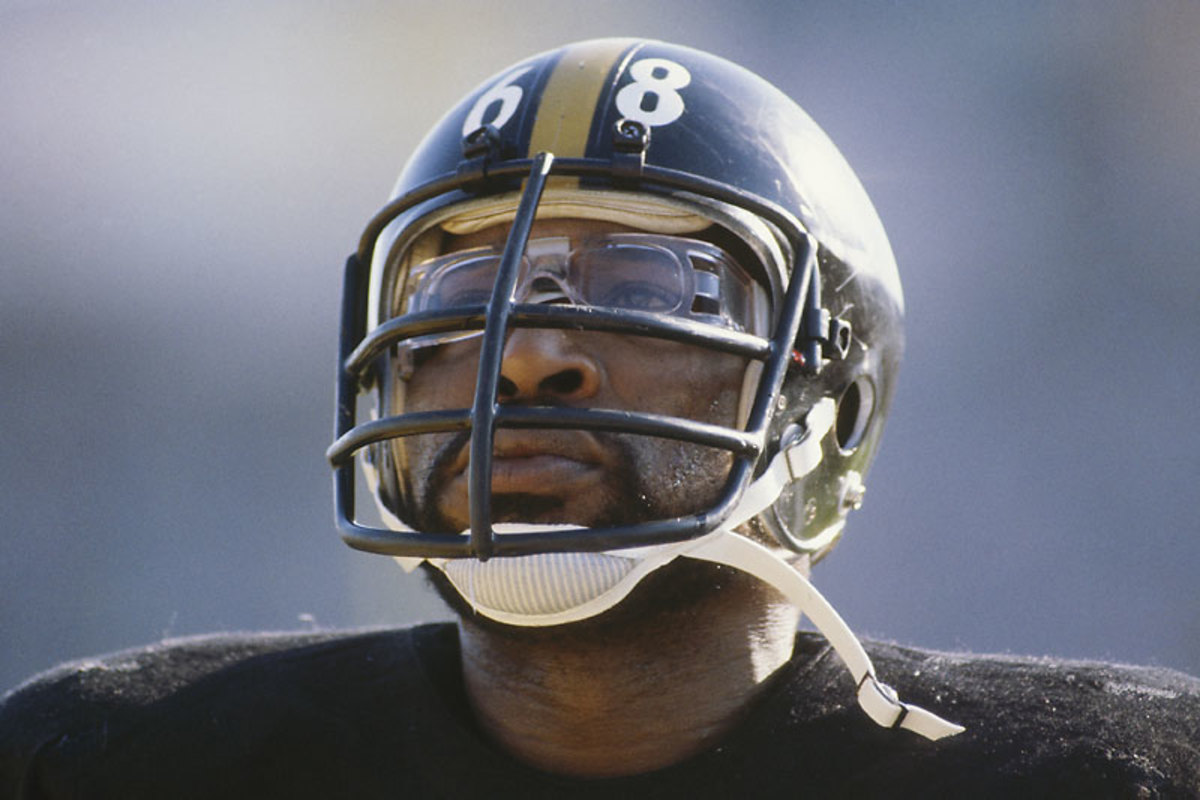

Holmes was nicknamed Fats, though his listed playing weight of 260 would be more fit for a linebacker than a defensive tackle these days. (Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated)

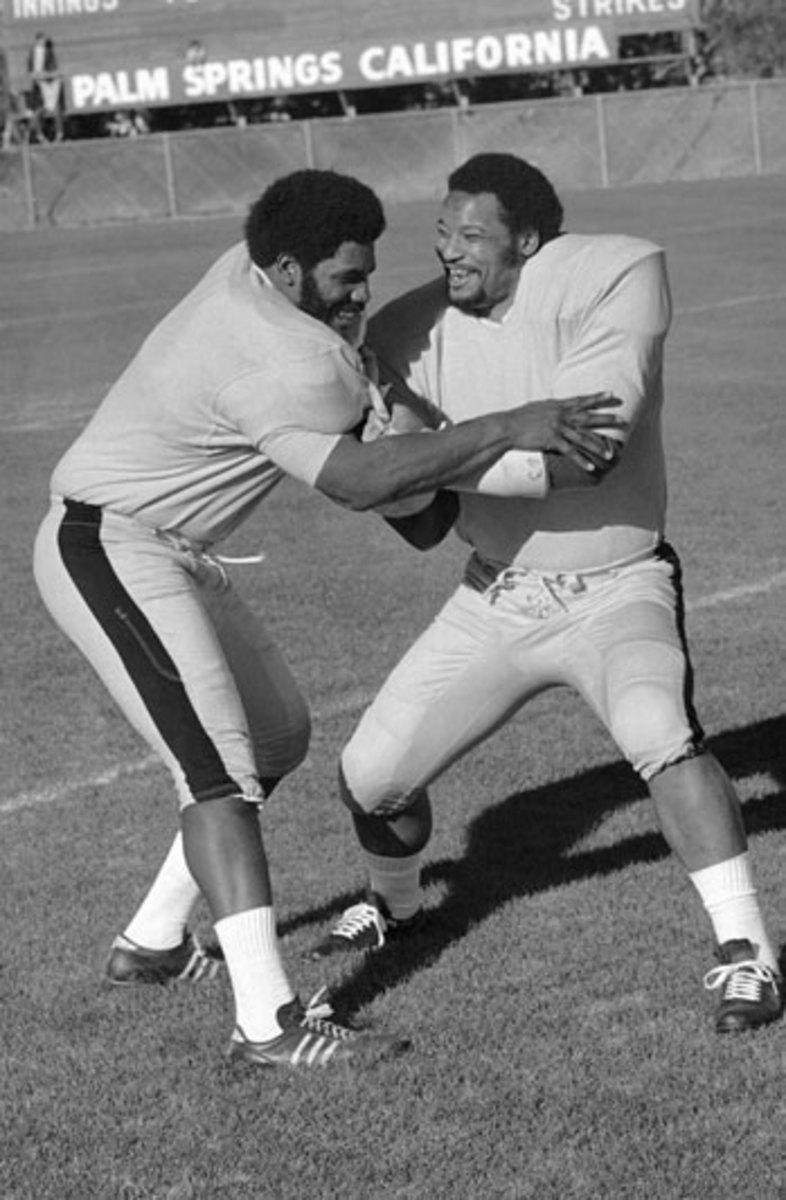

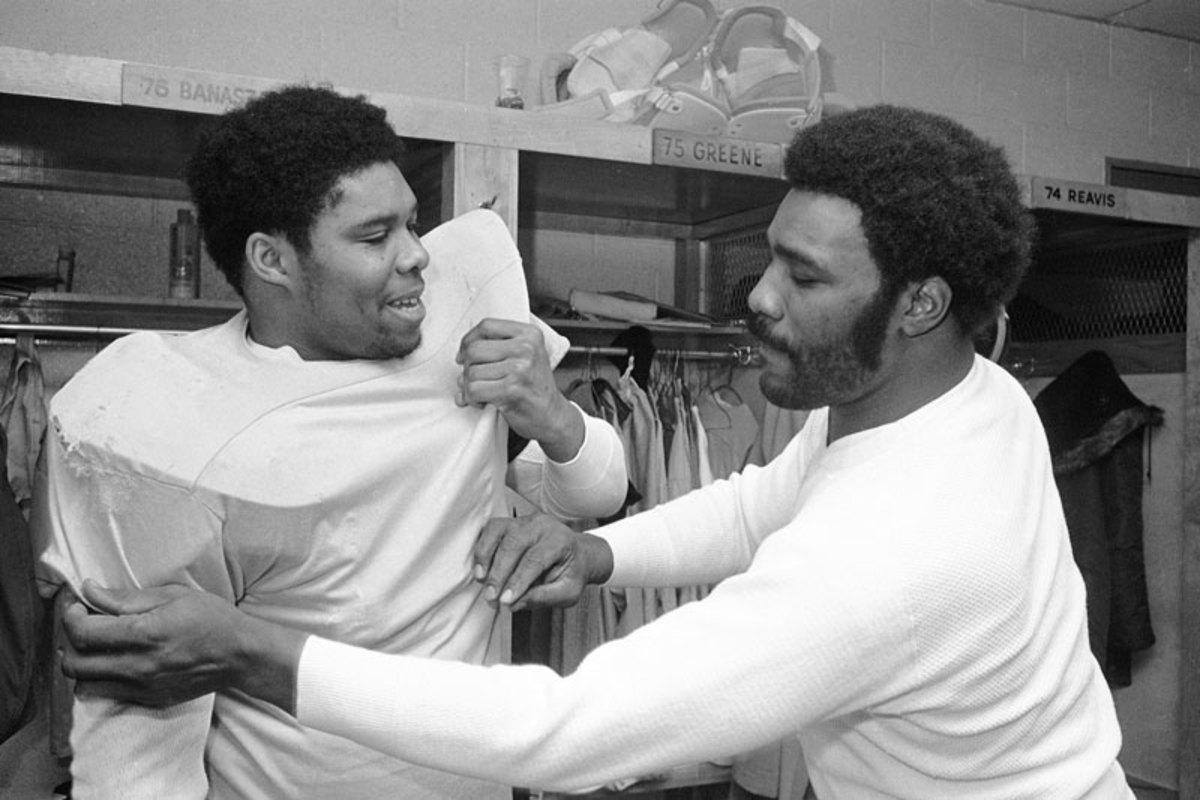

Greene and Holmes jostling in 1973. Greene was the fourth overall pick in the 1969 draft, out of North Texas State; Holmes was a 1971 eighth-rounder from Texas Southern. (AP)

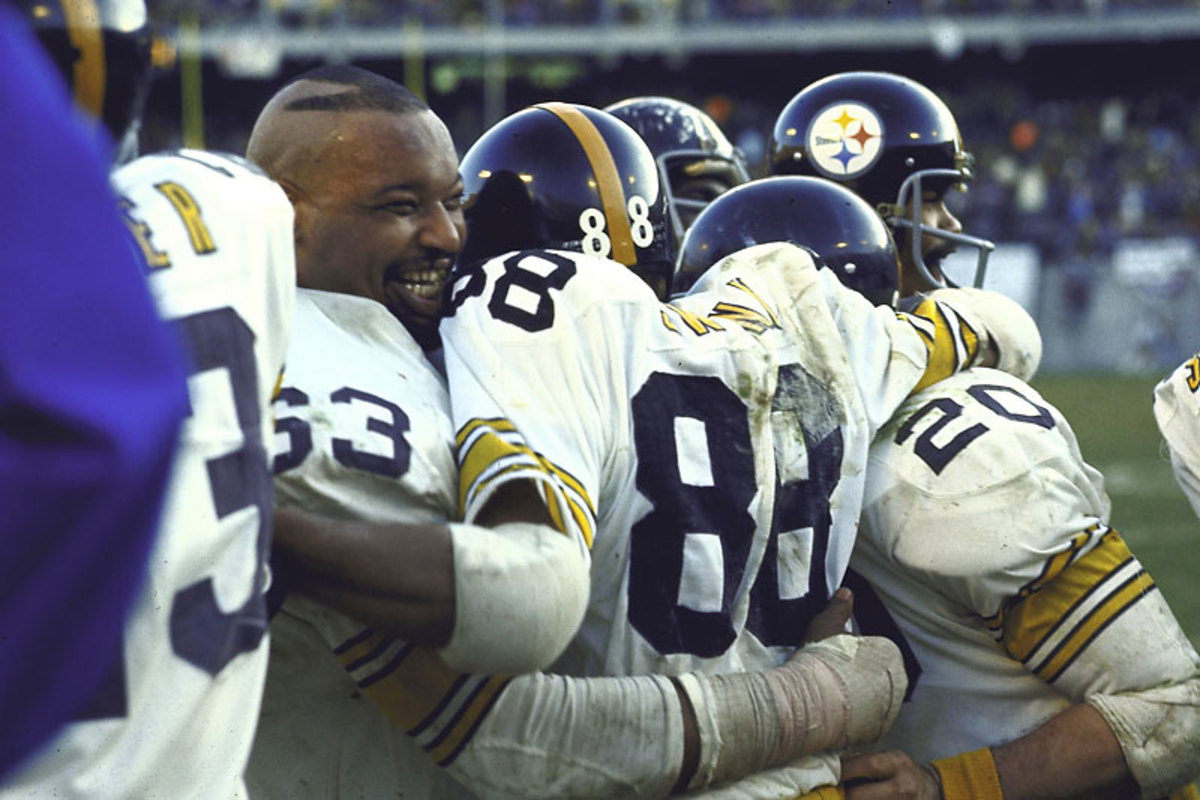

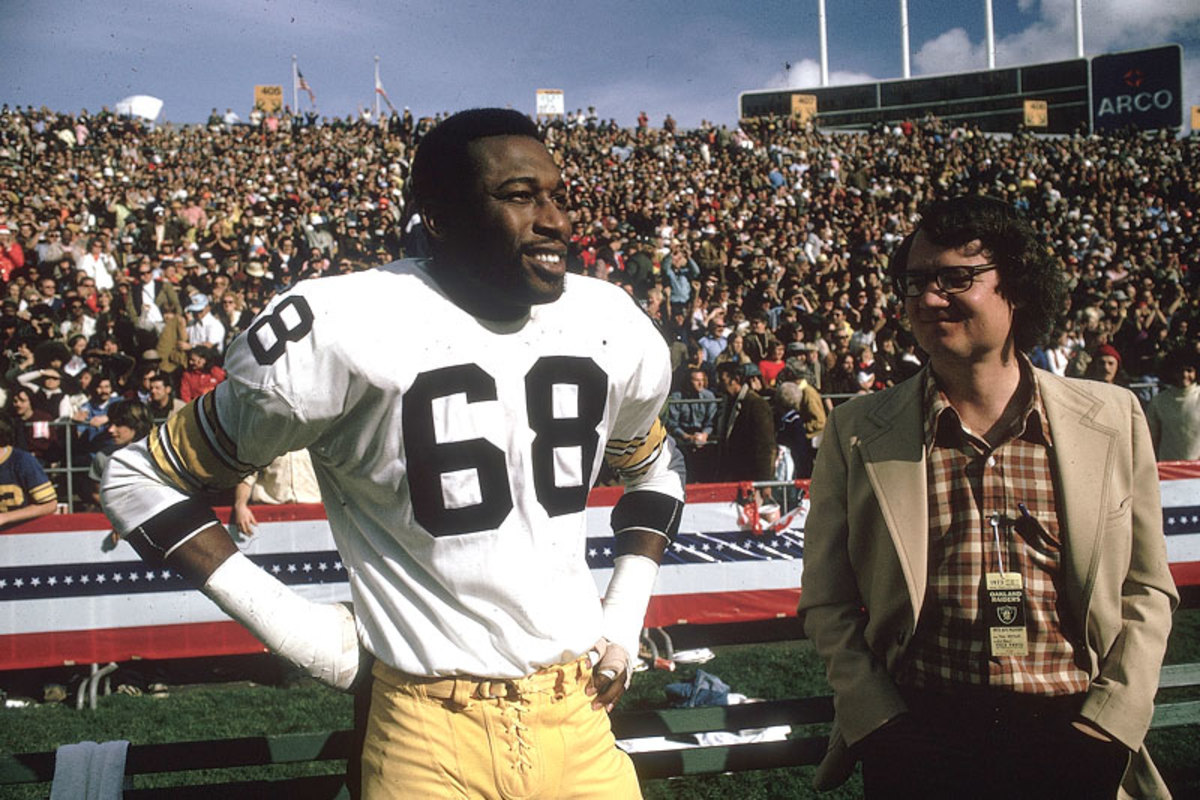

Fats, Lynn Swann and the Steelers enjoy a victory in the 1974 AFC Championship Game, and the Steelers’ first trip to the Super Bowl. (Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated)

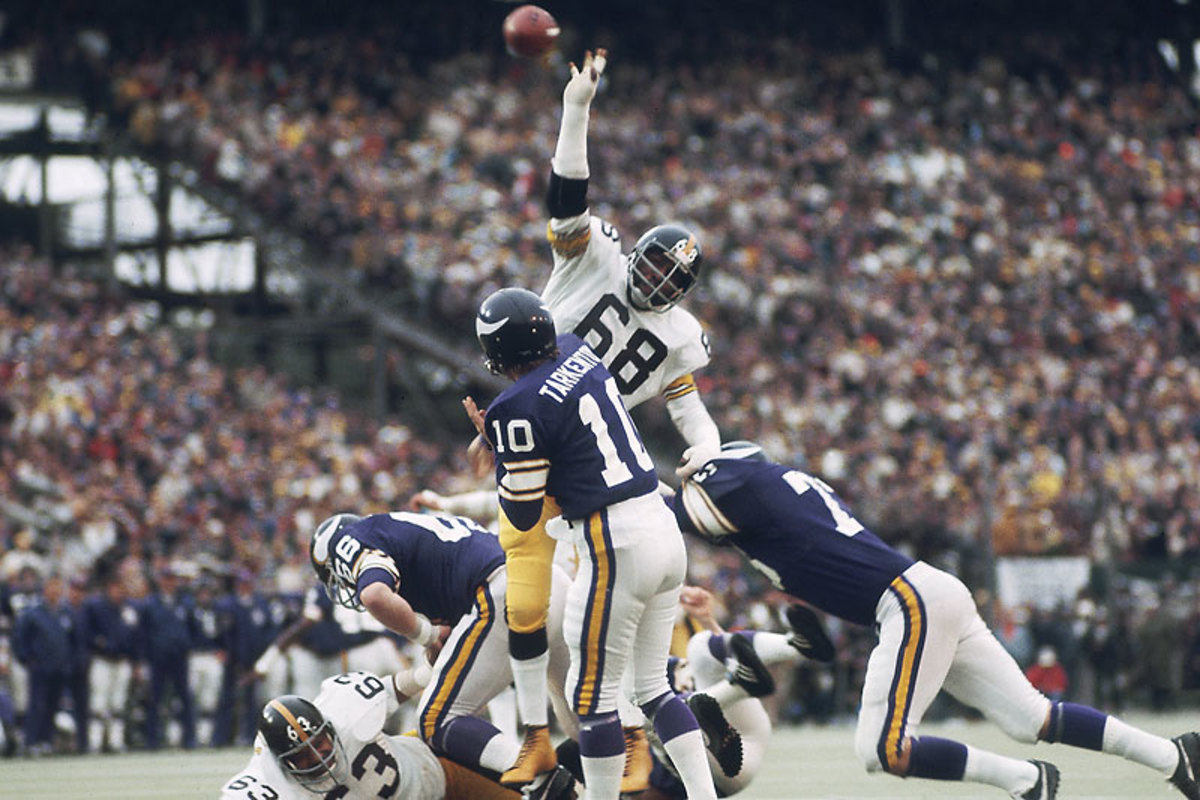

Wrapping up Minnesota’s Dave Osborn in Super Bowl IX. The Vikings gained just 17 yards on the ground. (James Drake/Sports Illustrated)

Holmes, Greenwood and Greene celebrate the 16–6 win over Minnesota, and Pittsburgh’s first NFL title. (James Drake/Sports Illustrated)

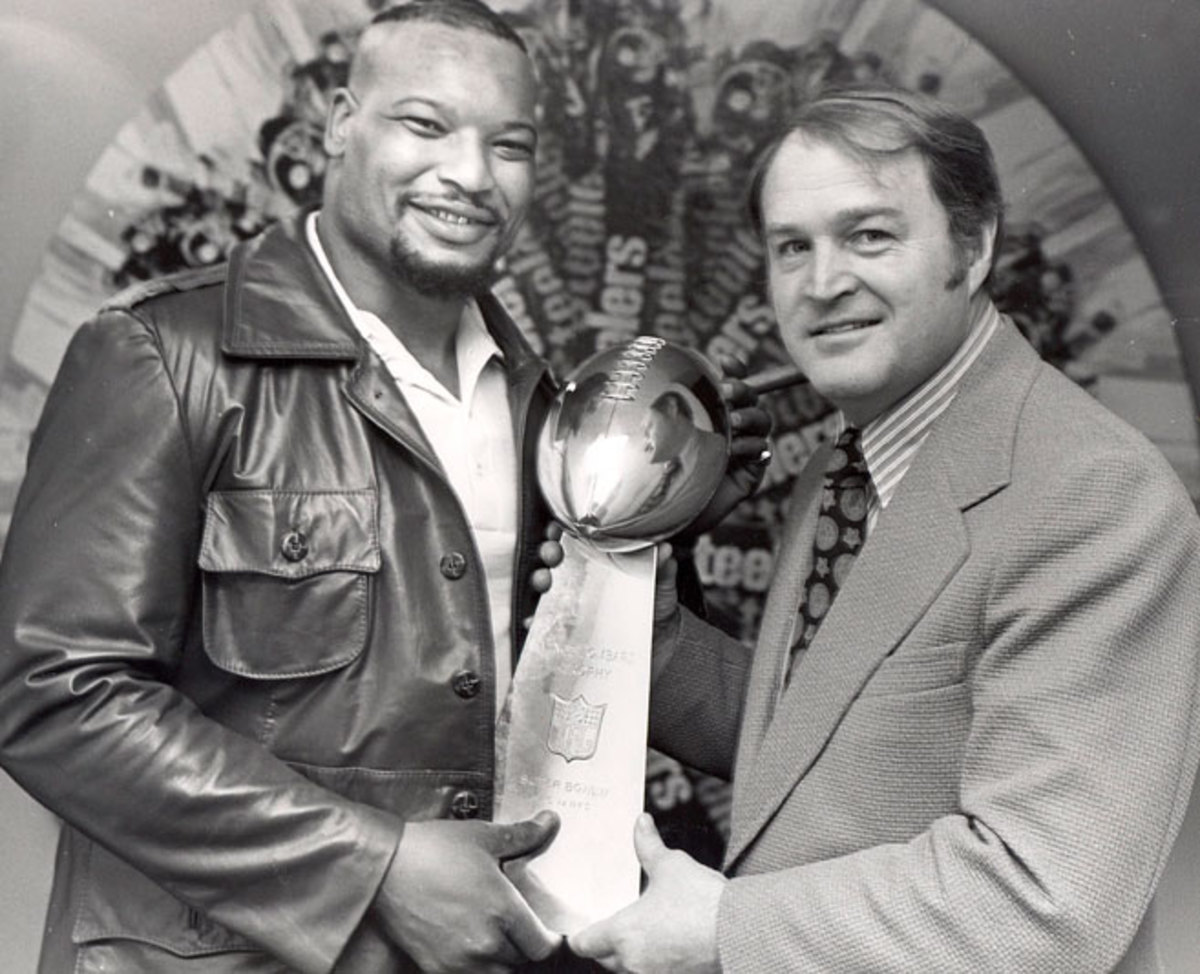

“Ernie is very much like Pittsburgh,” Chuck Noll once said. “Much better than its reputation.” (AP)

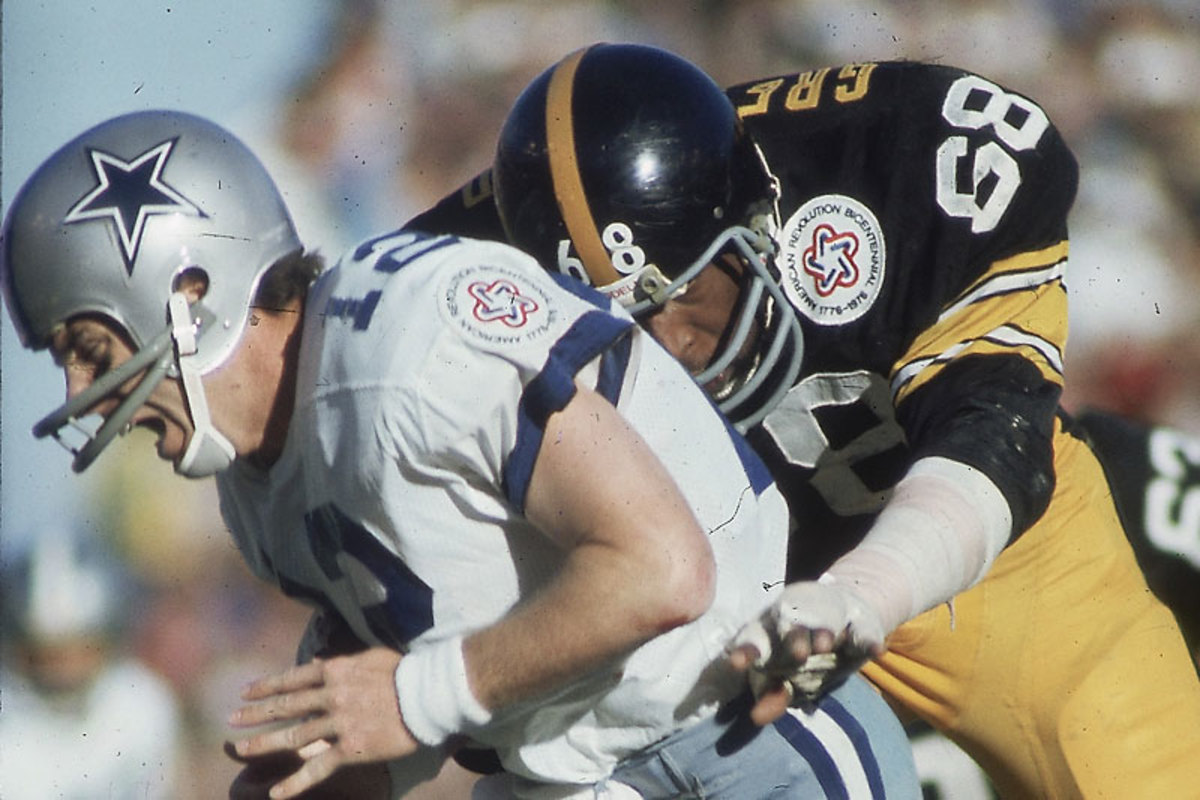

Holmes draws a bead on Robert Newhouse in Super Bowl X. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

By January ’76, Holmes had let his trademark arrowhead grow out. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

Ernie Holmes at a Steelers homecoming in 2007. (George Gojkovich/Getty Images)

Holmes preached sermons in small churches across Texas. Byron Holmes sent me a CD of one of his father’s sermons. On it, the Rev. Ernie Holmes’s voice explodes from the pulpit, and a small congregation calls back to him in the tradition of the southern Baptist black church. He cites biblical passages and defining moments in his life, including a day in March 1973 when he fired at trucks on an Ohio highway, and law enforcement chased him. He blew out a tire on his Cadillac, crashed, threw one gun out the window, grabbed another and some shells, ran through a field, and jumped a fence. Says the preacher, his voice strong and resonant:

“So I went out and set up camp to do battle with them … and then all the sudden this little kid called me and he said, “I’m cold.” I took my jacket off. I put it on him. … This helicopter flew over and I shot that helicopter. Now, look …I’m telling you the truth. I ran after I shot that helicopter, through some briar… And when I dove, a marksman shot at my head. … I put that barrel underneath my chin and rolled back and I shot at that marksman. … [But] the gun jammed. I threw the gun away and I sat [and called out] ‘Tell them to stop shooting’ … Then, all the sudden, I felt this guy [and he said], “Put your hands behind your back.” There was a state trooper standing behind me. And he said, ‘There are another 15 men looking at you with 12-gauge shotguns’ [and they were] pointing at the middle of my back. He asks, “Who else is out here with you?” I said, “That little boy.” He said, “What little boy?” I said, “That little boy that put my jacket on.” They went over there. He says he sees my jacket but there ain’t no little boy … Thank you, Jesus. The jacket was on this live oak tree with the limb sticking out. I said, “Thank you, Jesus. Thank you, Lord. You saved me.” They said, “How did he look?” I said, “I couldn’t tell you how he looked. The sun was so bright until I could not see his face but I put that jacket on him.” And that is the godforsaken truth. They wouldn’t put that in the paper. Because they ain’t gonna let you know how God saved [me]. … They ain’t gonna let you know that when you need somebody, you just say, ‘Jesus, help me!’”

In his sermon, Holmes talks about his Steelers teammates, too. “We loved each other,” he says.

“YEAH!” a man in church calls back.

“And that bond that you made,” the Rev. Holmes says, “is a bond between soldiers.”

“He loved those guys,” Byron Holmes tells me as we drive through East Texas, referring to the other members of the front four. “He talked about them all the time.”

On January 17, 2008, a Friday morning, Greene’s home phone rang in Texas, Steelers owner Dan Rooney on the line, saying, “Joe, I’ve got bad news for you. Ernie had a car accident and he’s gone.” On a dark night near Beaumont, Texas, Holmes’ SUV suddenly had bolted from the road, careened into a ditch and rolled over several times, killing him at age 59. Holmes had complained to family members recently about chest pains, and they were left to wonder if he had suffered a heart attack while driving alone in the night.

* * *

Joe Greene, and the Three Who Aren’t There

Dwight White on the bench in his rookie season, 1971. He was a fourth-round pick out of East Texas State. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

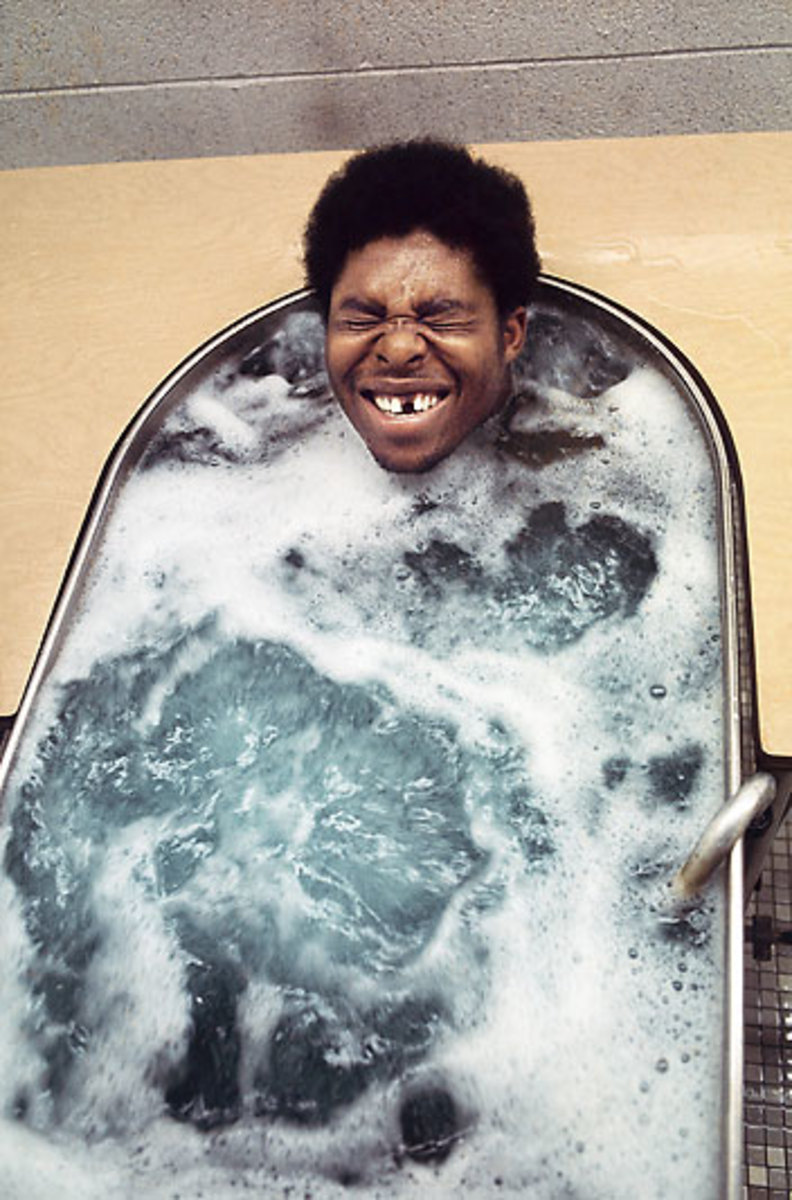

Chillin’ in the tub, 1973. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

Though hospitalized with pneumonia before Super Bowl IX, White was a force in the game. Overall, the Steelers held the Vikings to 119 total yards, still a Super Bowl record. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

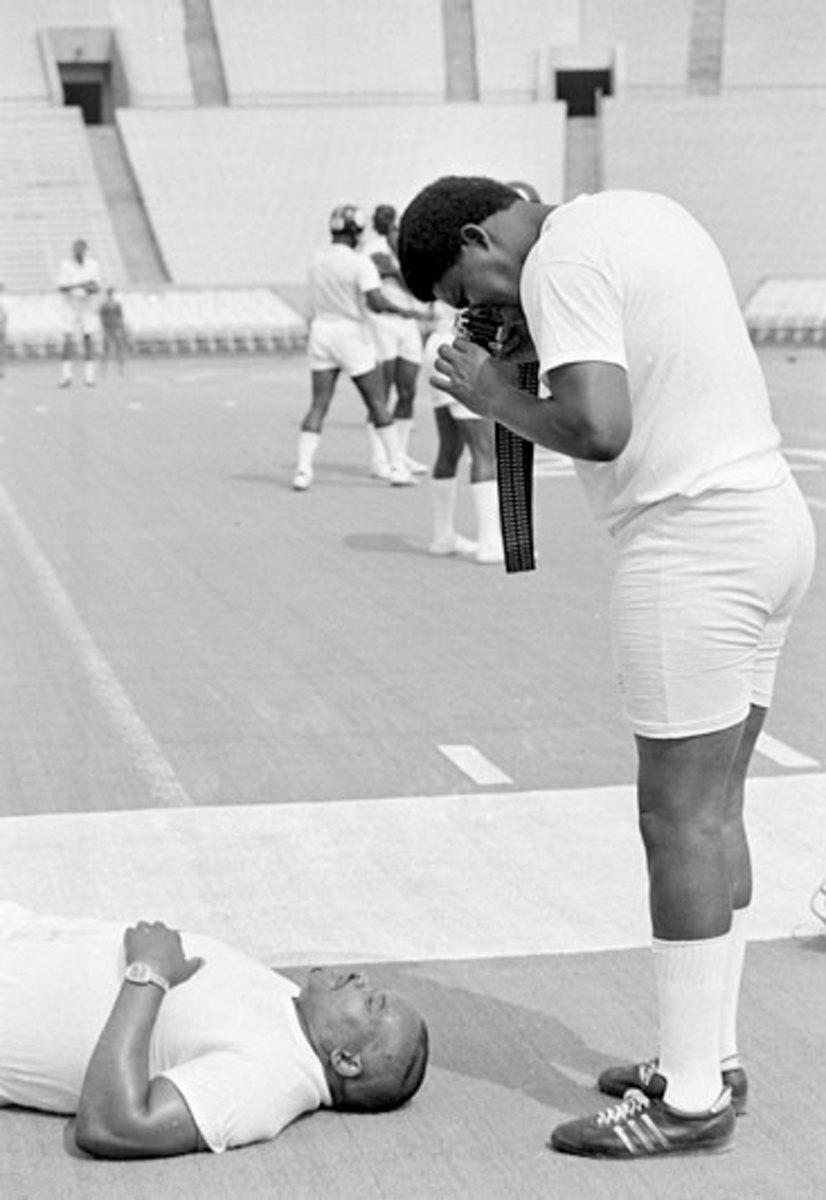

Mad Dog and Holmes goofing before the College All-Star Game in 1975. (AP)

White and Greene share wardrope tips in 1976. (AP)

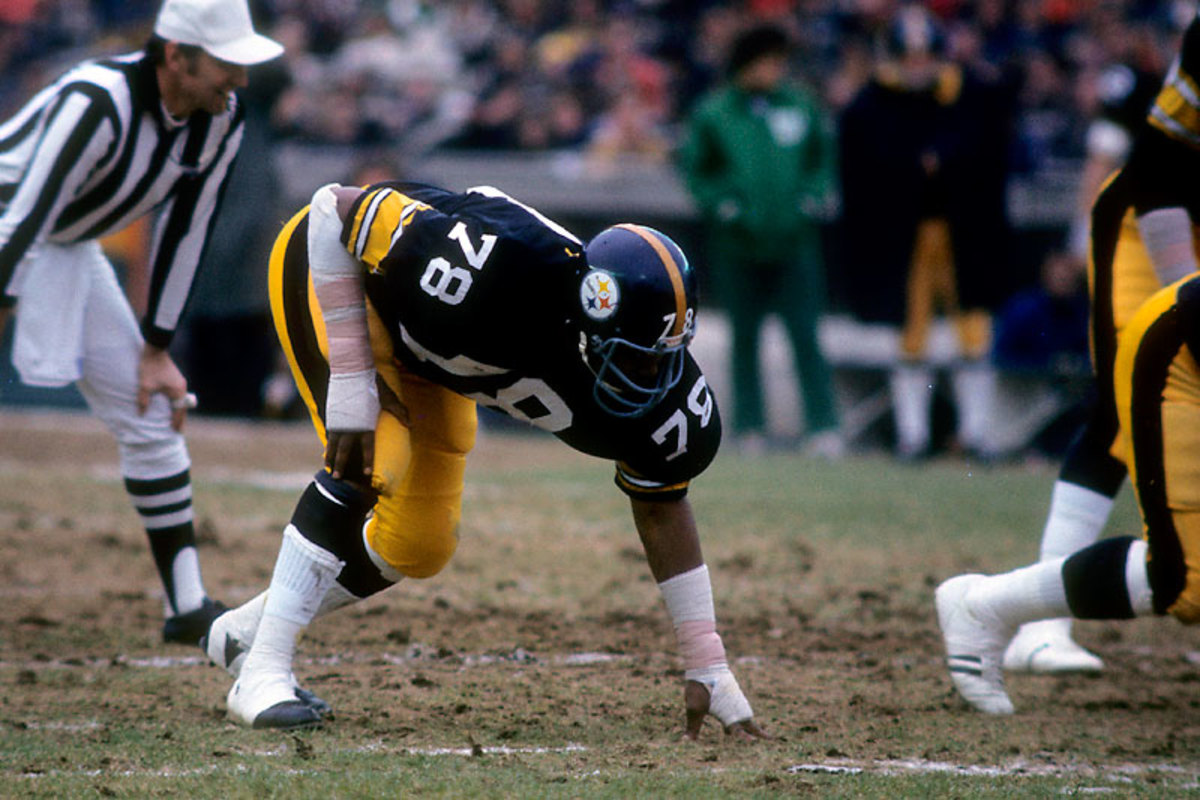

White manned the right side of the front four. He’s unofficially credited with 46 career sacks. (Focus on Sports/Getty Images)

Like Greene and Holmes, White was a Texas transplant who found fame in the ’Burgh. (Focus on Sports/Getty Images)

Pittsburgh Steelers were dying at an alarming rate. In July 2006, The Los Angeles Times reported that of the 77 NFL players from the 1970s and 1980s that had died since 2000, 16—more than one in five—were former Steelers. “I like us to have records,” Franco Harris told me, “but I don’t want that record. That’s very disturbing.” Of the 16, 10 were from the 1970s empire—Ernie Holmes became the 11th—and all died before the age of 60. The old whispers of rampant steroid use on those Steelers Super Bowl teams resurfaced. But John Stallworth brushed those away. “Fate,” was his explanation for the deaths. Stallworth noted the widely varied causes and circumstances of the deaths. A few died from disease: Ron Shanklin at 54 from colon cancer, guard Jim Clack at 58 from throat cancer and receiver Theo Bell at 52 from scleroderma and kidney disease. Defensive backs Ray Oldham and Dave Brown, single-season Steelers, died from heart attacks. The Old Ranger, Ray Mansfield, a bad-bodied center, had died even earlier, in 1996, from a massive heart attack while hiking in the Grand Canyon with his son. Mansfield, 56, was buried with a cigar in hand. Referring to possible steroid use, Stallworth said with a laugh, “If you saw Ranger’s body, you knew. Not him.”

“I don’t do funerals real well,” Greene said. “I’m an emotional person, you know? I care about people more than I let them know.”

Mean Joe, Mad Dog and Hollywood Bags sat together at the funeral for Fats in a high school gym that overflowed with more than 500 mourners, an old-fashioned home-going that lasted four hours and more. As the hearse carrying Holmes passed through the streets of Jasper, local police officers removed their hats and placed their hands over their hearts. Mel Blount and J.T. Thomas attended the funeral, too, and so did Art Rooney II, the Steelers’ president. In the front row, Greene, White, Greenwood, Thomas and Blount sat together in folding chairs, so closely bunched that their knees touched, and that closeness gave Thomas a heightened sense of comfort.

Mean Joe vs. Double-O

More from Their Life’s Work: In the 1974 AFC Championship Game, two all-time greats went nose to nose across the line of scrimmage. Steelers defensive tackle Joe Greene was at the peak of his power, Raiders center Jim Otto at the end of his career. Their showdown formed the centerpiece of the game that launched the Pittsburgh dynasty. FULL STORY

“You can see a person grow up,” Greenwood said, “and go from one extreme to another extreme. The transformation Ernie made, there was seriousness to it.” Greene spoke at the funeral, though no one had told him in advance so he hadn’t prepared any comments. He spoke briefly, from the heart, about the brotherhood of the Steel Curtain front four. Later, he told me, “I don’t do funerals real well. I’m an emotional person, you know? I care about people more than I let them know.” He sat in the gymnasium that day, head bowed, “just reminiscing about Ernie, about all of us. We won’t see him again. I’m sad for his family. I’m sad for myself.”

White returned to Pittsburgh from that funeral a changed man, a new and deep spiritualism flowing through him like music. He heard a church song at Holmes’s funeral, “I’m Just a Nobody Trying to Tell Everybody About Somebody Who Can Save Anybody,” by Lee Williams and the Spiritual QC’s. It affected him, played through his thoughts, and often in his car, too, on a CD. Greene noticed a change in White; they all did. “I get it now,” White told his wife, Karen. “I get this whole thing about life.”

On his trips to Pittsburgh, Greene nearly always paid visits to Mad Dog’s house. Together they grilled steaks, smoked Excalibur No. 1 cigars, had a few drinks and talked about the past, and now they reminisced about Fats, as well. They knew it wouldn’t be the same at card shows with the Steel Curtain front three. White broached the idea of leaving a vacant chair at future signings to honor Fats, or perhaps setting aside money to give to Fats’ church or Texas Southern or his children. They never got the chance to follow through on these ideas.

Several months later White underwent lower back surgery for a herniated disc. Greene phoned him from Texas a few days later to ask, “How you doin’?” Recuperating at home, White growled that he felt poorly and said, “Man, I’ve got to apologize. I can’t talk to you. I’ve got to go.” Greene went off to a NFL scouting event, where he received a call later from Greenwood. “Dwight’s back in the hospital,” Greenwood said, “and it’s not looking good.”

* * *

Joe Greene, and the Three Who Aren’t There

L.C. Greenwood corrals Roger Staubach in Super Bowl X. (Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

Greenwood with SI writer Roy Blount Jr., who chronicled the Steelers’ 1973 season. (Walter Iooss Jr./ Sports Illustrated)

Greenwood had one of the most memorable Super Bowl performances in history against the the Vikings, repeatedly swatting down Fran Tarkenton’s passes in his trademark yellow hightops. (James Drake/Sports Illustrated).

Typical of the savvy Steelers’ drafts of the day, Greenwood was plucked out of Arkansas AM&N in the 10th round in 1969. (Focus on Sports/Getty Images)

The old nemeses felt Greenwood’s force in an October 1979 rematch of Super Bowl XIII. This one, too, went Pittsburgh’s way, 14-3. (Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated)

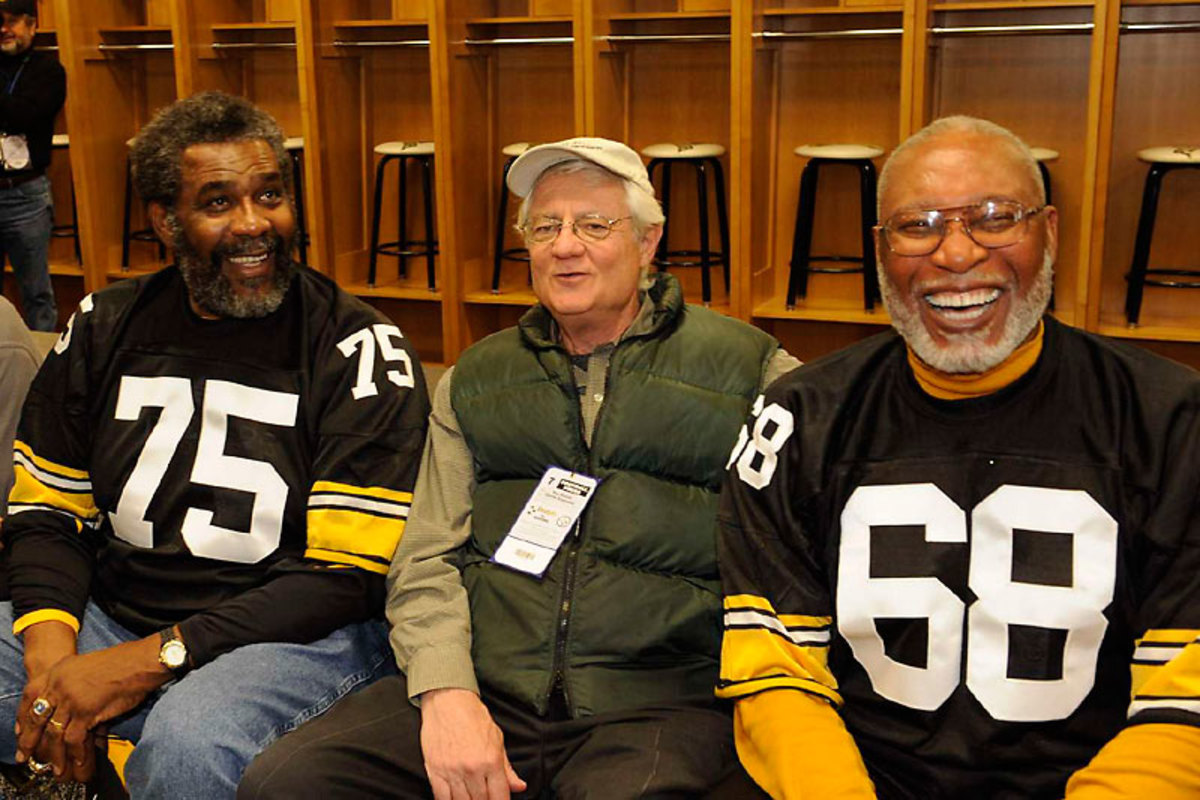

Greenwood, Mel Blount and Greene at a memorial for Dwight White after Mad Dog’s passing in 2008.

Greene, Roy Blount and Greenwood, November 2012. (Heinz Kluetmeier/Sports Illustrated)

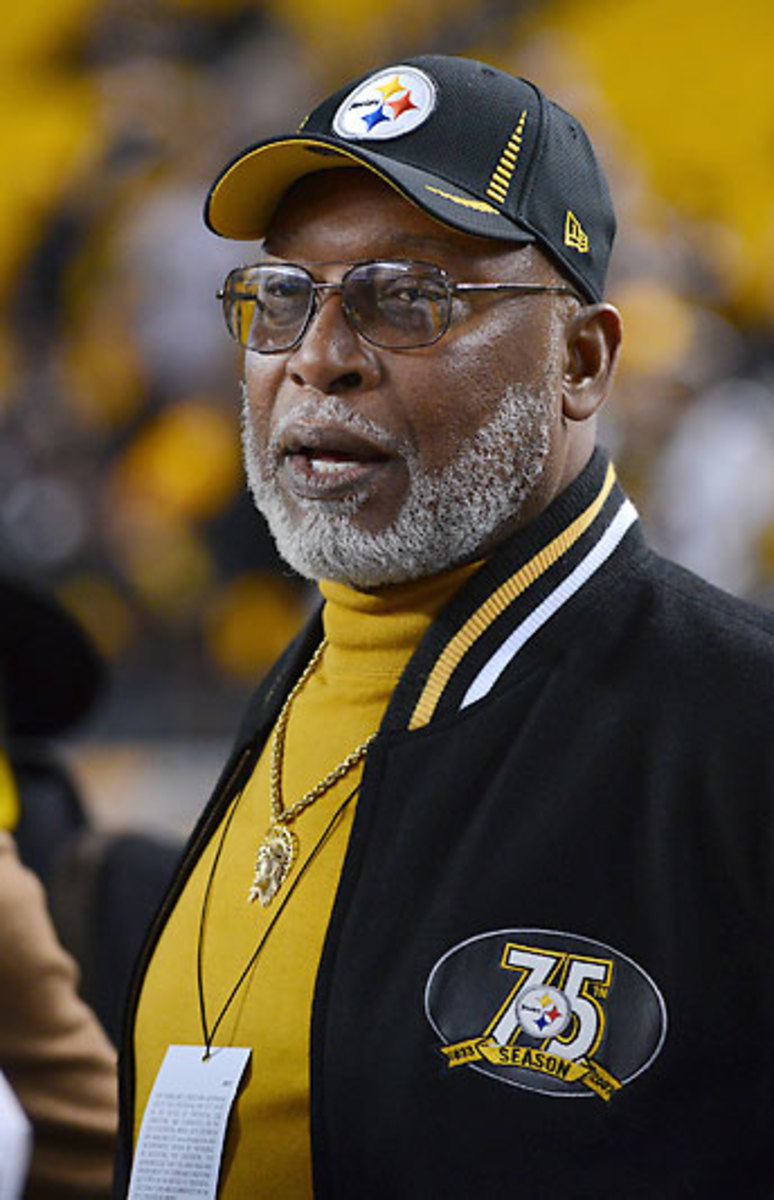

L.C. Greenwood, November 2012. (George Gojkovick/Getty Images)

Doctors diagnosed White with a pulmonary embolism, a blood clot in the arteries of his lung. Greenwood sat at White’s bedside in the intensive care unit of a Pittsburgh hospital. “Hooomes,” White told him, dragging out the syllable, “I’m in a lot of pain.” White always called him Home Boy or Homes or Hollywood Bags or H.B., but to Greenwood this sounded more dire than ever before, and it scared him. As White groaned, and faded into and out of awareness, Greenwood encouraged his old teammate, kept talking softly to him, to be sure he felt his presence. A nurse appeared. “Can’t you give him something,” Greenwood pleaded in a whisper, “for the pain?” She did, and White chattered on for some time, the meaning of his words not entirely clear, until finally he eased quietly into his medication. Greenwood waited another 10 minutes, watching over him, and then left.

Franco Harris became Greene’s information point man. Harris and his wife, Dana, as great friends of the Whites, visited the hospital daily. In the ensuing days there was hope that White’s condition might stabilize. Harris phoned Greene to say that doctors were about to remove White from a ventilator. Was it just a few hours later that Harris called back? It was, and his voice was pale and hollow as he told Greene, “He didn’t make it.” Dwight White was dead at 58, the 12th member of the 1970s Steelers Super Bowl teams to die before 60.

Greene at Dwight White’s funeral in 2008. Mean Joe is the last of the Steel Curtain front four remaining. (Keith Srakocic/AP)

Stunned, Greene phoned Karen White, and wept. In time his sadness turned to anger. How could this have happened? At Ernie Holmes’ funeral, Thomas had observed the new spiritual electricity in White. “Joe, you can be angry, but the Lord’s will is the Lord’s will,” Thomas said. “Dwight was ready.” But Mean Joe was not. He asked Thomas, “Do you think Dwight got in?” Thomas didn’t understand the question, so Greene clarified, “Did he get his act together with God?” Thomas said, softly, “I don’t know.”

More than a thousand people filled the church in Pittsburgh for White’s funeral—bankers, lawyers, politicians, and many former Steelers teammates, a testament to a full life. Gov. Ed Rendell spoke, and so did Greene. Delivering his second Steel Curtain eulogy in five months, Mean Joe spoke of his friendship with Mad Dog, just two ornery Texas guys, and about how his kids adored Uncle Dwight. White’s funeral was a respectful farewell, with less of the overheated emotion that charged Holmes’s funeral. “I guess there is a Texas way of doing things,” Greenwood said, “and a Pennsylvania way of doing things.” At one point during the funeral, Thomas smiled and whispered to Greene, “Dwight got in,” the notion of Heaven comforting to both.

Outside the church, Greene and Greenwood embraced. They felt more vulnerable than ever before. “We were the first to come,” Greenwood told him, “and we’re the last standing.” Much later, Karen White said, “Dwight’s death is really tough on Joe. He even has trouble talking to me. And I know what it is. He calls me and cries. He loved Dwight—and Dwight loved him—and he misses him.”

Editor’s Note: In September 2013, L.C. Greenwood died at 67 from kidney failure two weeks after back surgery. Joe Greene delivered a eulogy at Greenwood’s funeral. Today, the 68-year-old Greene is the only surviving member of the original Steel Curtain front four.