Where Pride Still Matters

Wellesley (in white) played Needham for the 127th time. (Winslow Townson/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

NEEDHAM, Mass. — The tables were set for the annual Tuesday dinner leading up to the Needham-Wellesley Thanksgiving Day football game, and the Rotary Club organizers had a surprise in store. Each player, coach and administrator was there to celebrate the oldest public high school rivalry game in America, but this year the teams were instructed to commingle at tables.

Boys from Needham and Wellesley, neighboring suburbs to the west of Boston, eating together? Making small talk? In the spirit of Thanksgiving?

The horror.

“We had kids asking us to overrule it,” a Wellesley assistant coach says. “They were desperate.”

“It was probably the most awkward dinner I’ve ever had in my life,” Needham senior Josh Celado says.

“It was a great night and we were appreciative,” Wellesley coach Jesse Davis says, choosing his words carefully, “but maybe those kind of ideas were thought up by people who’ve never played in the game.”

This rivalry is among the hundreds of games played on Thanksgiving morning in Massachusetts and elsewhere throughout the country. To outsiders, there’s little difference between these two affluent towns, where the median household income is more than double the national average. But Needham kids say their counterparts from Wellesley are snobbish and overwhelmingly white collar; Wellesley students label their Needham rivals as “fake tough guys.” Most of them played youth football together until the program split six years ago, only deepening the rivalry. The old-timers feed into it, too. At the Rotary Club dinner, alums from the 1960s and ’70s bragged about who won the game as seniors in high school.

“You look forward to it every year,” says Wellesley senior TJ Noonan, a fullback. “We’ve known every single player on that team since we were kids. It’s not just a game. It’s something that defines our communities.”

* * *

Frustrated by NFL players’ misdeeds and fueled by personal experience, fullback TJ Noonan started a domestic violence campaign at Wellesley in September. (Winslow Townson/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

Noonan began going to the Thanksgiving Day game when he was in fifth grade at a private school. In 2010, when he was in eighth grade, Needham beat Wellesley, 20-17, on an improbable overtime touchdown throw. Needham students rushed the field. Noonan was hooked. No way he was going to go to private school for high school and miss out on the rivalry.

Wellesley’s football team soon became a family to him, sometimes replacing the real thing and giving Noonan an escape. “Domestic abuse has directly affected my life,” he says bluntly, sharing few specifics other than his parents’ split. “It altered my family structure. The first thing I did was look to the football program, and I think it created a stronger bond with my teammates. It’s not about what happened, it’s about the response.”

In early September, the Baltimore Ravens cut Ray Rice after the elevator video of him knocking his fiancée unconscious surfaced. Noonan decided to take a stand. He wanted to wear a purple bandana around his leg during Wellesley’s next game as a tribute to domestic violence awareness, so he called his friends and fellow captains to seek their input. They loved the idea. He called his coach to make a formal request the Wednesday night before Friday’s game. Jesse Davis, a short and stocky former Marine with a fierce glare, doesn’t shine on whimsy or individual flair. His motto for the season: One Heartbeat.

“I asked my coach if I could wear something purple,” Noonan says. “And he said, ‘Anything you do, we have to do as a team. The whole program’s going to wear it.’ ”

The next morning, after Noonan and his mother combed the town for purple bandanas, the school encouraged Noonan to announce the team’s plan to the student body on the intercom. “People started asking me for purple bandanas to wear,” he says. “The business department got involved and bought a bunch of purple stuff to sell to the students.”

Everyone wore something purple to the game instead of the school’s colors—black, white and red. “I just wanted to wear a bandana,” Noonan says. “Before you knew it, you couldn’t get a purple bandana in Wellesley, Needham, Framingham or Natick. A.C. Moore must’ve had a really good week.”

The effort raised $300, and Noonan had a charity in mind for the proceeds: He once worked with a shelter for family victims of domestic violence, the Bristol Lodge Women’s Shelter in Waltham. The team plans to make the donation after the season.

“Watching all of the arrests and suspensions for NFL players really struck me,” Noonan says. “Everybody can say it’s an NFL problem, but it’s not even a football problem; it’s a cultural problem. It gets amplified because these guys are stars, but it happens in countless homes all over America. It’s our problem and our responsibility.

“I think with domestic violence you can feel alone. That week made me feel like I wasn’t alone and other people understand.”

While there is probably nothing that can stop the boys from Wellesley and Needham sniping each other across town lines, they had more in common than they realized when they sat down together for dinner. With every Thanksgiving class they share the same memories, the same heroes, and even the same tragedies.

* * *

Needham coach Dave Duffy (l.) and Wellesley coach Jesse Davis. (Winslow Townson/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

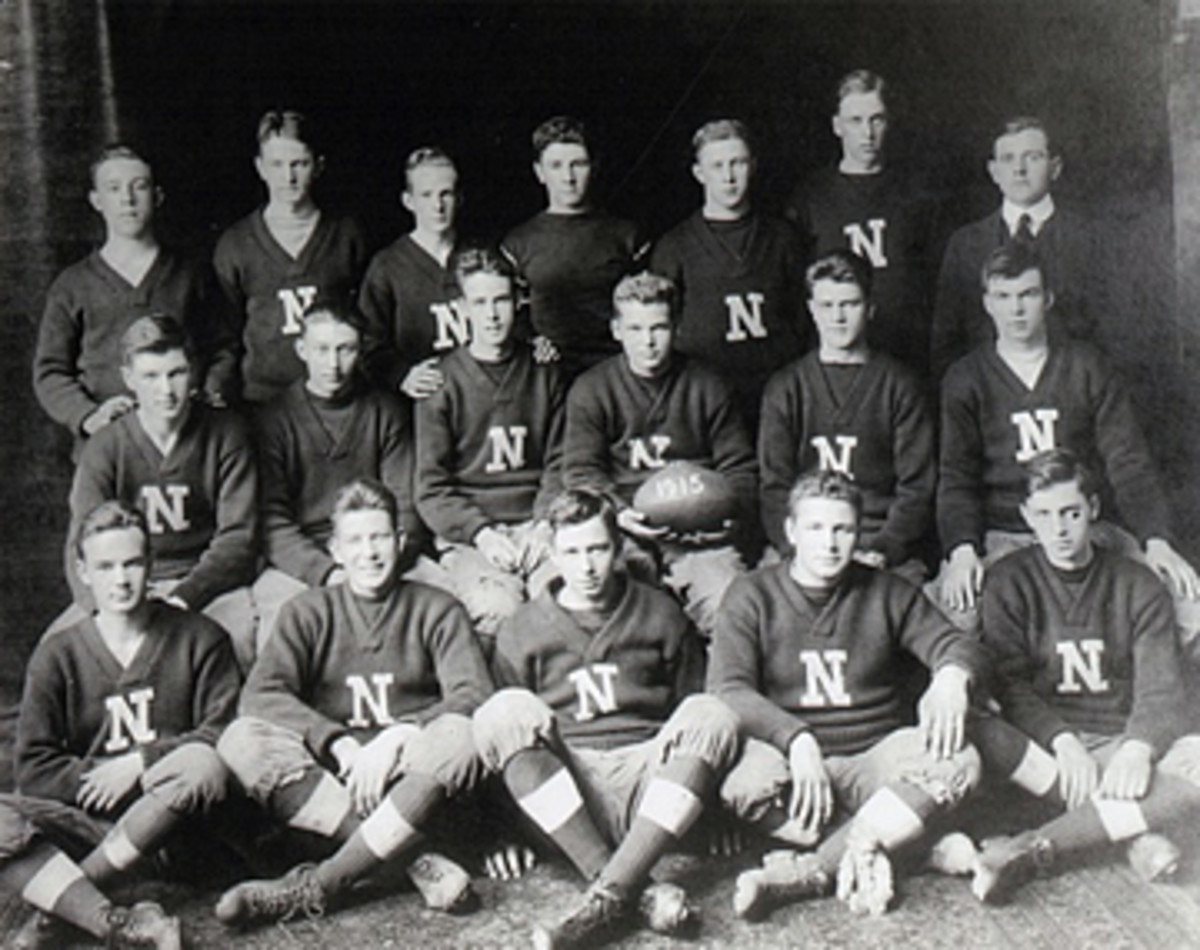

Duffy’s grandfather (front row, center) played for Needham on the 1915 team. (Courtesy photo)

Both head coaches played in the Thanksgiving Day game—Dave Duffy graduated from Needham in 1983 and Jesse Davis from Wellesley in ’99—and Duffy was a third-generation participant. His father graduated from Needham in ’52 and one of his grandfathers played for the school in 1915 and ’16.

Duffy, now in his 17th year as Needham’s head coach, keeps portraits of both men in uniform in his home. Smiling and perpetually in motion, he joined the program as an assistant 30 years ago and never left, reaching a Super Bowl in 2011 (a state championship game) and winning Massachusetts’s Coach of the Year award in 2012. One of his philosophies: set no rules in stone.

“I tell them on the first day, ‘When you screw up, my treatment of you is going to depend on how much I like you,’ ” says Duffy, whose team went to the playoffs this season. “What they don’t know is that I like them all. I feel like if you treat boys like adults, they act like adults, but if you treat them like little kids and set up a bunch of rules…”

Duffy’s willingness to adapt served him well in the case of Josh Celado, a brash senior who swears he saw one Wellesley kid raise his pinky while sipping a glass of water at the Rotary Club dinner. Celado was an unknown commodity last season, and his lack of experience was hurt by the fact that he kept missing practices on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. He eventually told coaches that he was responsible for watching his younger siblings and couldn’t stay after school on those days.

Duffy looked into it and found it to be true. Celado had first transferred to suburban schools through METCO (Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity), which busses volunteer inner-city Boston students to suburban high schools. His parents had split when he was in fifth grade and living in Boston, and to escape his father, they lived on and off in a women’s shelter before finding government subsidized housing in a small corner of Needham. In high school, he was responsible for taking care of his five siblings, including now 6-year-old twins, a few days a week.

Needham’s Josh Celado often missed practice to care for his siblings last year. (Winslow Townson/SI/The MMQB)

“We live in Needham and everybody thinks we have perfect lives,” Celado says. “But you know, every family has their problems. Domestic violence is something I grew up with.”

Josh thinks of his siblings as his own kids. He and a brother who is 10 months younger would go home straight from school to supervise and feed the others—usually peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and fried plantains—while mom worked menial jobs.

“Unfortunately, Josh had to grow up fast,” his mother, Linda Garica, says. “He witnessed a lot of things, so he’s very protective of me. People ask him if I’m his sister and he gets very angry.”

His mom’s employment situation improved this year—she’s now a health care administrative assistant—and he’s been able to make every practice. He blossomed during the final month of the season and has played nearly every position on defense. “He was just learning on the fly, and you could see him pick up new things every day,” Duffy says.

* * *

Wellesley QB Jake Mohan throws against against Needham in the second half. Below, a Wellesley team photo during summertime training with former soldiers. (Winslow Townson/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB :: Courtesy photo)

Over the summer, Wellesley football boosters paid for the team to attend Camp Caribou in Winslow, Maine, where they trained on the water with The Program, a group of ex-soldiers who have also done leadership development work with Oregon and Nebraska’s football teams.

The regimen jibed with the coach’s personality and military background. Davis is described by players as having strict policies, including a curfew on game nights that he personally enforces with phone calls home. He also hands down suspensions for being late even by a matter of seconds. That’s just fine with senior wideout Jack Dolan, the Raiders’ emotional leader.

Needham’s Lucas Goldman couldn’t stop this touchdown pass to Wellesley’s Griffin Morgan. (Winslow Townson/SI/The MMQB)

“I unfortunately was 90 seconds late to a game and I was suspended for the first drive,” Dolan says. “I think it shows us that it’s about more than being an individual. Like Bo Schembechler said, No man is more important than The Team. The Team. The Team. The Team.”

Jake MacDonald, one of several former marines with The Program and a veteran of three overseas deployments, put the team through boat drills and awarded a paddle for excellence in leadership to Dolan, who carried it with him as he led Wellesley onto the on Thanksgiving morning. Before the game, MacDonald, a Massachusetts native, spoke to the team in the locker room.

“Think about the things you need to do to be successful. Being a good teammate, working hard, being physically and mentally tough. Will doing all of those things guarantee you a win? No, it won’t,” he said. “You do all those things and you are guaranteed an opportunity. Opportunity is knocking right now, men, I can hear it. How will you answer the door?

“I told you there were three kinds of people in this world: Losers, winners and champions. Men, when opportunity knocks, losers don’t even answer the door. They’re sleeping on the couch, drunk, high, whatever. Winners, men, they’ll answer the door, sometimes. But they’ll look through the peephole first to make sure it’s not too difficult. Too risky. Then they’ll open it, cautiously. But men, champions? When opportunity knocks, champions step up, kick that mother down, and start pulling triggers.”

Had there been a brick wall between the Raiders and the field, they would’ve pulverized it.

Jake Mohan, a junior quarterback playing in place of an injured senior captain, found Dolan in the end zone for a 12-yard touchdown, Dolan’s 16th of the season. Late in the first quarter, however, Dolan’s attempt to punt from his own red zone in a shotgun formation was blocked by Celado and recovered by at the 2-yard line. Needham’s Sam Hurvitz tied the game at 7 on a touchdown plunge. On the extra point, Dolan, Wellesley’s best player, rolled his ankle.

* * *

As the story goes, this rivalry began in 1882 when Wellesley schoolboy Arthur J. Oldham challenged a group of boys from Needham—the town from which Wellesley had seceded two years earlier—to a football game. Challenge accepted. The high school organized a fundraiser to pay for a ball, priced at $3.50. Wellesley won, 4-0.

Through the years the rivalry saw the slimming of the regulation ball and the introduction of the forward pass, and survived a four-year hiatus during World War I. The history has its murky spots and ignominies. It’s been said that Needham called off the 1914 game rather than face sure defeat and potential bodily harm against the eventual state champions. Yet Needham backers are quick to remind critics of the lax age requirements and eligibility standards of the day. The 1887 game ended in a tie after fans from both sides swarmed opposing ball carriers just before they reached the end zone. In the 1980s, it became an unofficial tradition to stage a non-sanctioned powder puff game in which female students from both schools would gather at a discreet location and play an alcohol-fueled game that often devolved into violence. (The powder puff game became sanctioned and legitimized in the ’90s.) In 1991, the actual Thanksgiving Day game was delayed after it was discovered that students had buried a rocket beneath the field and planned to set it off after kickoff. (It didn’t go off and no one was hurt.)

But perhaps the best stories come from the 1970s, which Jason Hasenfus, a Needham police officer and the son of local legend Gigi Hasenfus, shared at last Tuesday’s dinner.

Legendary stories define the rivalry. Students once buried a rocket under the field. And fans have jumped into the fray to make tackles.

“My father was in his early 20s, back from Vietnam. He’s standing there in the back of the end zone while we’re playing Natick, a good football team,” Jason says. “Natick is marching and they’re kicking Needham’s ass. And my father turns to a cop and another guy and says, ‘Natick is not gonna score again. You watch.’ They say, ‘What do you mean, Gig?’ Naked bootleg, two linemen are free sailing, lead blocking. My father comes out of the back of the end zone, onto the field, blows up these two kids and tackles the quarterback.”

Hasenfus pauses, trying to catch his breath from laughter.

“The coach is screaming, ‘What the f---?! Are you f------ crazy?!’ And my father says, “Maybe I am a little!” The cops walk him down the dirt road to the cruiser. And he goes, ‘C’mon guys, I’m not a criminal. I’m a veteran. At least take the cuffs off.’ They take the cuffs off, and he takes off running, and that was that.”

A few weeks later, Needham was playing at Wellesley. Gigi’s cousin was the captain of Needham’s cheer squad. As Jason tells it, “His cousin says, ‘Gigi don’t do anything to embarrass me.’ Well, what do you know, Wellesley breaks around the end, they’re going for an 80-yard touchdown, and my father steps out from the sideline and puts a perfect form tackle on this kid. Boom! The crowd is in a hush. The announcer goes, I think a fan just tackled the runner! He gets up and before the cops could get him he disappears into the crowd. They didn’t give the kid a touchdown, they ended up spotting it where he got tackled. Many years later my grandma showed me the article from the Needham Times: Unknown Needham Man Tackles Schoolboy Football Player.”

* * *

With a 27-13 victory on Thanksgiving, Needham is two wins away from tying the series, in which Wellesley holds a 60-58-9 edge. (Winslow Townson/Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

After Dolan turned his ankle, nothing seemed to go right for Wellesley. The running game, led by Noonan, largely stalled. Mohan was sacked six more times, including a hit in the first half that caused him to bite down on both lips. He had to change his jersey at halftime because of the blood and go to the hospital for postgame stitches.

In the second quarter, Needham quarterback Sam Foley connected with Cliff Kurker for a 68-yard touchdown pass. Kurker, who wears the team’s only high-top fade and plans to play lacrosse at UMASS Lowell next year, wears an X under one eye and a dash of eye black under the other—a nod of respect to Tyrann Mathieu. Coincidentally, Dolan, Wellesley’s star, does the same. He even wears No. 7 to emulate his favorite NFL player, the tenacious Cardinals defensive back who, he says, “covers like Patrick Peterson and tackles like JJ Watt.”

After injuring his ankle, Dolan played only a few more plays in a 27-13 loss. Needham is now two wins away from tying the series, in which Wellesley holds a 60-58-9 edge.

At his brother’s house in Millis, Needham coach Dave Duffy wasn’t exactly greeted as a conquering hero. He shared the spotlight with his nephew, a coach at Millis who also won his Thanksgiving Day game, and with a stack of pies made painstakingly by wives and sisters who’ve seen enough football over the years to know they don’t have to pay attention until the final fives minutes of regulation.

Duffy avoids the pie and all the other sweets. He’ll soon be retiring from the Needham fire department after suffering a heart attack earlier this year. He was told the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery of the heart was 99% clogged when it happened. “It’s stress, but I can handle the football stress,” he says. “My first four years I lost the first four Wellesley games and my own friends were questioning me.”

In another town, over another feast, Wellesley coach Jesse Davis thought about the season as a whole—bouncing back from four straight losses to win six in a row—and came to roughly the same conclusion even though the Raiders didn’t make the playoffs or close out the season with a victory.

“We came together as a team, and it was incredible the way they rallied,” he says. “But you talk to alumni, fans, everybody, and nobody asks what your record is.

“They just ask, ‘Did you beat Needham?’ ”

Follow The MMQB on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]