I’m Not Russell Wilson, But I Play Him on TV

SEATTLE — Players stretch on the sidelines under the lights at CenturyLink Field. They toss footballs and trade wisecracks and tug helmets over heads. They wear eye black and wristbands and full uniforms.

The game starts. The hometown Seahawks break the huddle. Their quarterback spies a large defensive lineman from Green Bay just over the ball.

“Who are you supposed to be?” Russell Wilson says.

“I’m the guy who’s tackling you,” the large defensive lineman responds, then cackles.

The quarterback laughs back. Nervously. He calls the play, drops three steps, evades defenders and launches a deep pass, which a receiver snags between safeties in the end zone. It’s the same kind of pass, to the same corner, that Wilson threw to Golden Tate for a last-second game-winner in 2012 against the Packers, the so-called Fail Mary.

Wilson trots to the bench. Another quarterback trots on to the field. He does the same stuff as Wilson, except this time the quarterback gets tackled. Repeatedly. Hard. This QB looks like Wilson. Same build—low to the ground, thick. He is dressed like Wilson. Same No. 3 jersey, same white towel tucked into his pants, same lime-green cleats.

The other quarterback is not Wilson. Nor is this a real game. The play never changes. The stands are empty, the din of the crowd piped in. A small city of producers, directors, makeup artists and the like stand near midfield. It’s July.

The other quarterback is Randall Bacon. He played high school football in Sacramento, setting all sorts of records, as he bounced among the homes of relatives. Poor grades forced him to play in junior college, then at Texas A&M Kingsville, rather than Division I, but he performed well enough to draw Boise State’s attention, at least until he suffered an injury in 2006 at Kingsville.

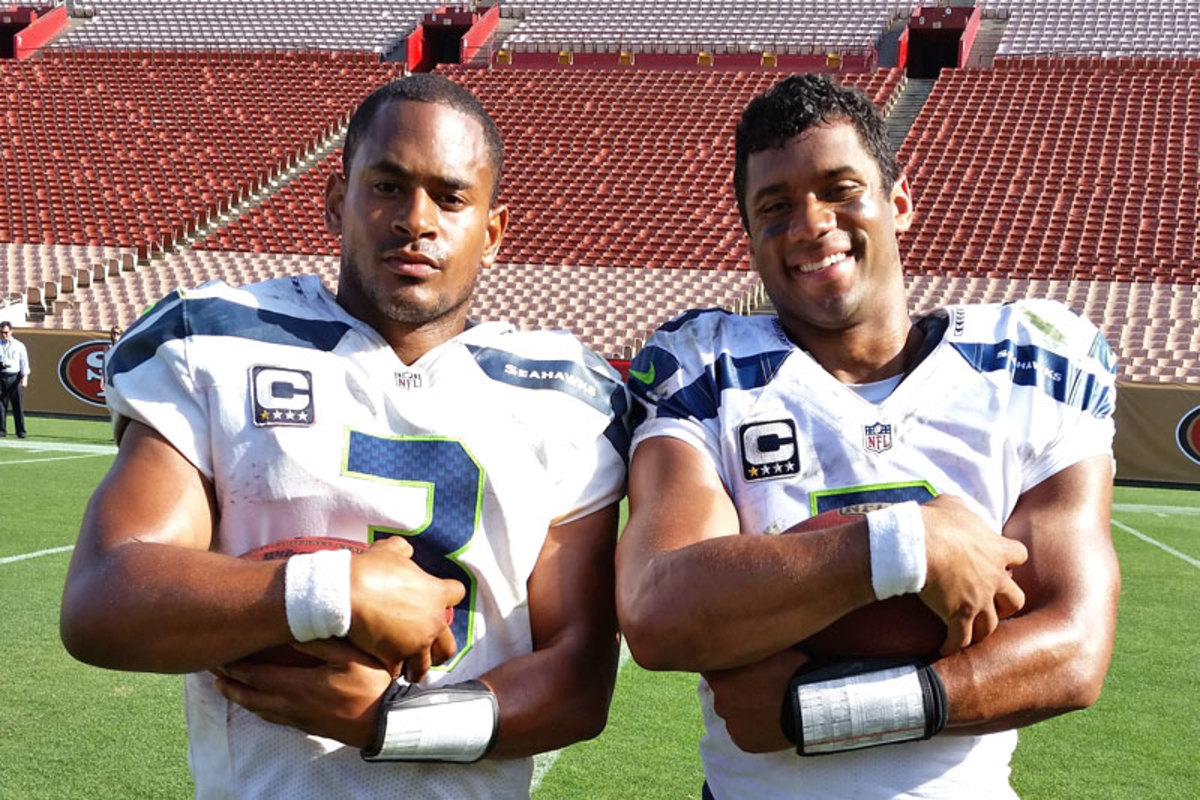

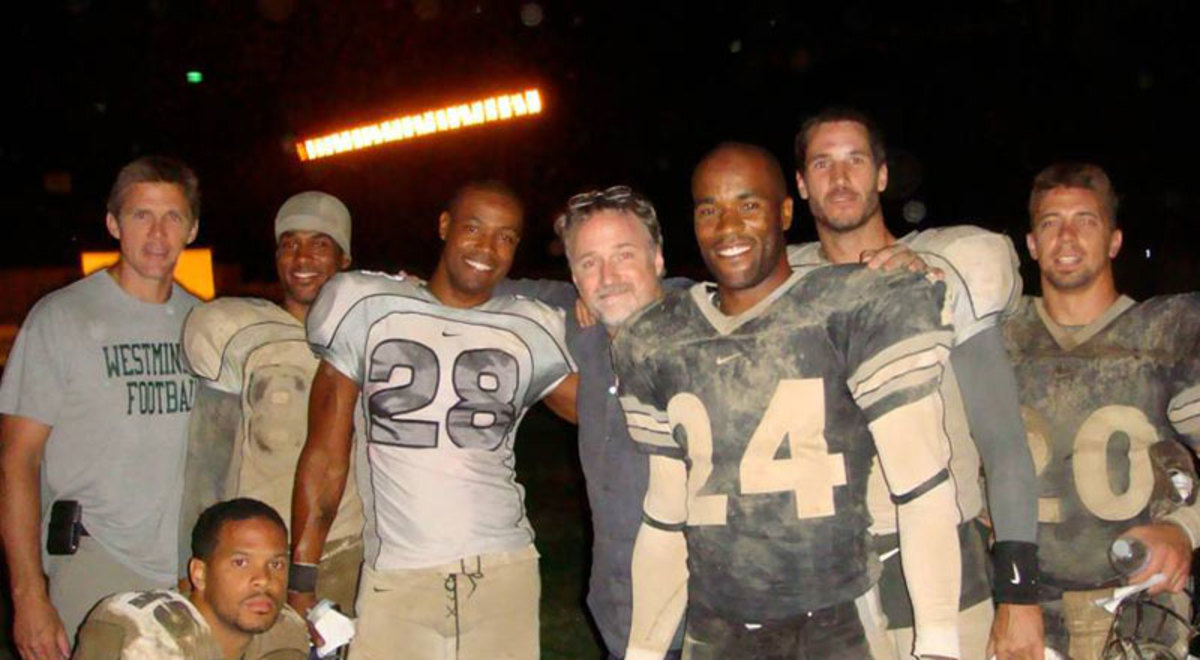

Randall Bacon (left), who played junior-college ball and at Texas A&M Kingsville, alongside Wilson during the filming of a commercial. (Courtesy Randall Bacon)

While still there, Bacon visited his girlfriend, a model, in Los Angeles. At her test shoot for a print advertisement, the photographer asked him to step in.

He never returned to Texas. Bacon became a model and an actor and a stuntman. He slept on friends’ couches and borrowed the $2,600 he needed for a Screen Actors Guild membership. He did dozens of football commercials and worked for companies such as Nike and nabbed a part on The Young and the Restless.

Bacon recently landed the gig as Wilson’s stunt double, and because Wilson won the Super Bowl last season and snagged myriad endorsements, both men have been busy. Bacon estimated that in 2014 he earned more than $100,000 as Wilson’s double.

When he moved to Hollywood, Bacon discovered a subculture filled with others like him. Most had played Division I football, or had the talent to, and suffered an injury or fought with a coach or failed a drug test—only to discover that they could still don pads and clown teammates and play football. Commercials, movies and video games are their way back in, another chance at gridiron glory. Just as in real football, the goal is to stick to the script. Bacon sees the same guys over and over. They're the same guys viewers see on television during commercial breaks—stand-ins, like Bacon for Wilson. As the Seahawks marched into the NFC Championship Game with a victory over Carolina, Bacon also survived another week. Those Bose ads playing on seemingly endless loop? That's Wilson. And Bacon, too.

“This,” he says, as he gestures about the field, “is my new team.”

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZQAANmSEGxs&w=800;h=450]

* * *

Athletes want to be actors. Actors want to be athletes. Those who do the football movies and commercials are sort of both and sort of neither. They’re not like Alex Karras, the Detroit Lions great who later landed roles in Blazing Saddles and Porky’s and starred on Webster for seven seasons; or O.J. Simpson, the Hall of Fame running back who appeared in Roots and The Towering Inferno and the three Naked Gun movies. But they’re also not like Isaiah Mustafa, who did football commercials until he landed an Old Spice campaign and became a sensation, or LaMonica Garrett, who transitioned into Sons of Anarchy and Transformers. Not yet, anyway.

These guys fall somewhere in between. They’re good enough at football to make it appear realistic but not good enough—or lucky enough, or healthy enough—to make it as pros. They’re handsome enough to be on television but struggle to find jobs beyond the football gigs. Many work as insurance salesmen or policemen or bartenders or personal trainers, taking time off to shoot commercials and make some extra cash. They want flexibility. Many of them drive for Uber now.

Chauncey Washington, here in a shoot for SI’s 2007 college preview cover, is another in a long line of USC Trojans who’ve found football work after football. (Peter Read Miller/Sports Illustrated)

The money can be solid or life-changing, depending on the number of gigs they get and what kind of role. Principal actors are the ones in the shot, taking the hits for Wilson, or delivering them for Patrick Willis. They’re classified as body doubles, and they often earn twice the regular day rate.

That means between $650 and $800 a day on set, and if they’re also classified as principal actors, they receive residual payments from larger media markets (around $5,000) and Internet buyouts (about $3,000) for each 13-week commercial cycle. If the commercial gets picked up for additional cycles, they make all that money again. And again. And again, for however long the ad continues to be aired. They can even negotiate higher rates between cycles, depending on the popularity of the spot. Background actors, by comparison, make between $300 and $350 a day, without residuals.

The most visible commercials, the ones that play constantly in lead-ups to various seasons, can net an actor $50,000 for two days’ worth of work.

As in real football, competition for jobs is stiff, and career windows are limited. Younger actors replace older ones and injured ones. The coordinators who work with the players expect them to be punctual, cooperate with directors, synchronize with wardrobe, give full effort. Players hope for regular work. Some won’t tell their friends from real football about the opportunities that exist. Omar Nazel, a defensive lineman on USC’s 2003 national championship team, did that once, and his friend landed a gig as Brandon Jacobs’ body double, an act of kindness that Nazel thinks cost him $40,000.

USC, thanks to its Los Angeles location and proud heritage, produces more football actors than any other school. The latest: Chauncey Washington. For years he kicked around NFL practice squads, trying to latch on at running back. Now, he plays a running back on TV.

* * *

These players didn’t plan to act like they play football. They planned to actually play it. They looked forward to long NFL careers, Pro Bowls, lucrative endorsements. The only commercials they would film would be the ones they starred in.

Then life happened …

Dionté Holloway sensed a breakout season in 2006. He had transferred to Utah State from Fresno State, became the kick returner, earned reps at receiver. Then, he says, a teammate who had been accused of sexual assault brought some marijuana to his room. Police knocked on the door. Coaches kicked him off the team. He played arena football, stumbled into modeling, then commercials. One director asked him about his comfort level with all the repeated blows he received during shoots. “S---,” Holloway told the director. “I used to get hit for free.”

Omar Nazel actually started off as an actor. He performed at his church as a mime in a group called the Silent Prophets, but later switched to football and played at USC. He loved the interviews, loved the camera, loved to act, and he considered a career in sports broadcast journalism. Then he did a commercial that starred Peyton Manning. Then a movie, The Comebacks. The director: Tom Brady. No, not that Tom Brady. “I’m like, wait a minute,” Nazel says. “This is a real thing?”

Former USC Trojans Mazio Royster, Sandy Fletcher, Sunny Byrd, Troy Polamalu, Omar Nazel (kneeling), Gerald Washington, Sulton McCullough and Lee Webb, on the set of a Head & Shoulders shoot. Only one of them is a real Steeler. (Courtesy Sunny Byrd)

Lee Webb spent time on the Jacksonville Jaguars’ practice squad, and when that stint ended—locker-room politics, he says—he had no plan, no idea what to do. He became a coach at Palos Verdes Peninsula High, tried to latch on to the staff at his alma mater, USC and, in his spare time did a Verizon commercial that starred Clay Matthews. He made $30,000 for 10 hours of work. He decided not to coach last season.

Kenny Bell’s career at Hofstra fizzled because of injury. But he hung on to football, first in tryouts for NFL teams, then with the Evansville BlueCats of the United Indoor Football League. He does motion-capture work on video games, takes thousands of hits, runs hundreds of sprints and performs everything from juke moves to touchdown celebrations. One time a tackler cracked him on the head and his right foot went numb.

Michael Jordan—no, not that Michael Jordan—played at Michigan State. A broken foot derailed his pro prospects. He became an investigator for child protective services, an experience he describes as “traumatizing.” Then a friend recruited him to Los Angeles to box. He moved on a whim and won 10 amateur bouts. After all those blows to the head, he turned to acting—and more blows to the head. “I’m living both dreams,” he says. “My plan is to retire Denzel.”

That’s how this team that never plays was put together—by chance, mostly, with players who wanted to act and who never considered acting, whose college careers ended by force or by choice, with the injured and the lucky and the aimless. They arrived in Hollywood like so many others. They knew somebody. They dreamed big.

Take Chris Robbins, who, after quarterbacking at Clemson in the ’90s, tried out for Any Given Sunday, doubled Keanu Reeves in The Replacements and worked on Remember the Titans and Friday Night Lights. He became a pastor and a stuntman and a coordinator for all these football shoots. “The process is almost like group therapy,” he says. “It gave me a lot of closure, a lot of peace when I walked away.”

* * *

Football players turned football actors gather for a team photo. Seated from left: Dionté Holloway, Mathew Childers, Mazio Royster, Travor Turner, Randall Bacon, Jeff Sanders, Brandon Jefferson, Omar Nazel, Kenny Bell. Standing: Arden Banks, Jason Scott Jenkins, Sunny Byrd, Ross Bacon, Chris Robbins, Michael Jordan, Damion Owens, Michael Craven, Sandy Fletcher, Derek Graf. (Joey Terrill for Sports Illustrated/The MMQB)

The Team That Never Plays has a fluid roster. It changes constantly, based on the actors’ availability, the number and type of players required and the whims of various casting agencies. Estimates vary, but hundreds of ex-jocks look to supplement their incomes with commercials and movies and video game jobs. Some do multiple sports, but for football specifically, maybe 40 get regular work. Of those, fewer than half, maybe a quarter of them, make six figures. It’s always hardest to find linemen.

The Team That Never Plays has coaches. They’re called coordinators, and they’re responsible for making fake football appear as real as possible. They also often pick the players, which makes them general managers and scouts.

The Team That Never Plays has a season. Two, actually. One comes in July, before the college and pro teams kick off, when the work is constant. The commercials filmed in July begin to air before those seasons start. There’s another run of new commercials that you’re seeing now. Those were filmed before the bowl games and the NFL playoffs, to run during the big postseason games. Otherwise, work is scarce.

I’m Not Russell Wilson, But I Play Him on TV

Former Trojans D-lineman Nazel (left) has the build to double any number of players—including Megatron. (Courtesy Omar Nazel)

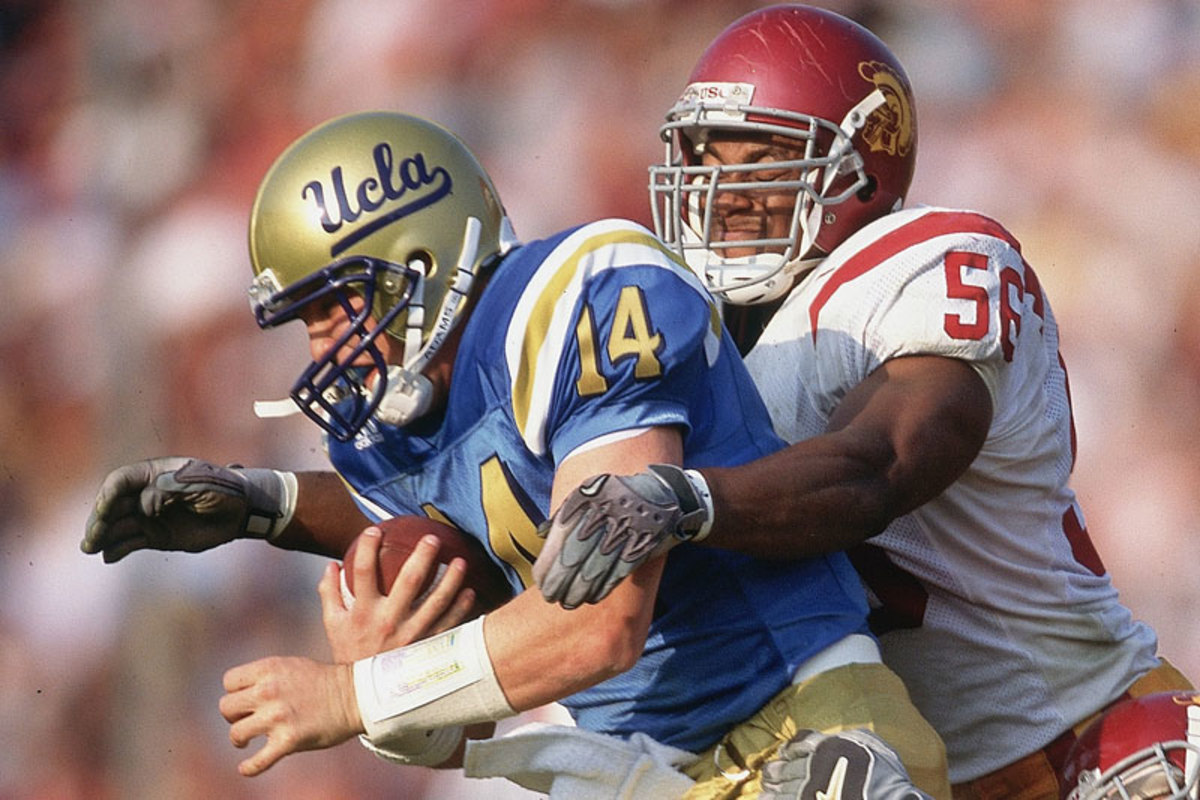

Nazel making a tackle with USC in 2002. (Peter Read Miller/Sports Illustrated)

An undrafted free-agent in 2004, Nazel made it to the last round of cuts with the Seahawks. (Chris Bernacchi / SportPics)

Nazel says he scouts up-and-comers whom he might double someday. He’s got his eye on Jameis Winston. (Courtesy Omar Nazel.)

The Team That Never Plays does scout work. The players scour college football rosters, looking for future stars with similar body types and complexions—guys they can someday stand in for. Nazel is 6-5 and weighs about 240 pounds. He has doubled Calvin Johnson and Cam Newton and Larry Fitzgerald, and he keeps an eye on Dolphins defensive end Dion Jordan should his play ever match his draft status (third overall, 2013), and Jameis Winston, the former Florida State quarterback and potential No. 1 draft pick this year, who is about Nazel’s size. Coordinators, meanwhile, look for players who flirted with NFL rosters. One coordinator, Jeff Sanders, finds guys at the mall. Some reach out to sports information offices at major West Coast schools. “You have to recruit, just like college coaches,” Sanders says.

The Team That Never Plays trains as if it will. The players lift weights and box and do CrossFit. They run and sprint and repeat the agility and footwork drills they learned in school.

The Team That Never Plays deals with injuries. Bacon, for instance, doubled Wilson for a Duracell commercial, where he was met—and crunched—by the body double for linebacker Patrick Willis. The spot required 25 takes—25 straight head-on collisions. Bacon thinks he suffered a concussion but says, “It’s OK. I don’t have to get cleared.” Shoulders have been separated, collarbones broken, fingers jammed, ankles twisted, bodies flipped, kidneys torn. Football, basically. Availability, as in the NFL, is as important as ability. Play hurt in one area, act hurt in another. But it’s not an act.

The Team That Never Plays could beat some teams that do. “We would crush semi-pro teams,” Robbins says. “If we had the resources and the time, I guarantee we’d beat a college team, too.”

* * *

I’m Not Russell Wilson, But I Play Him on TV

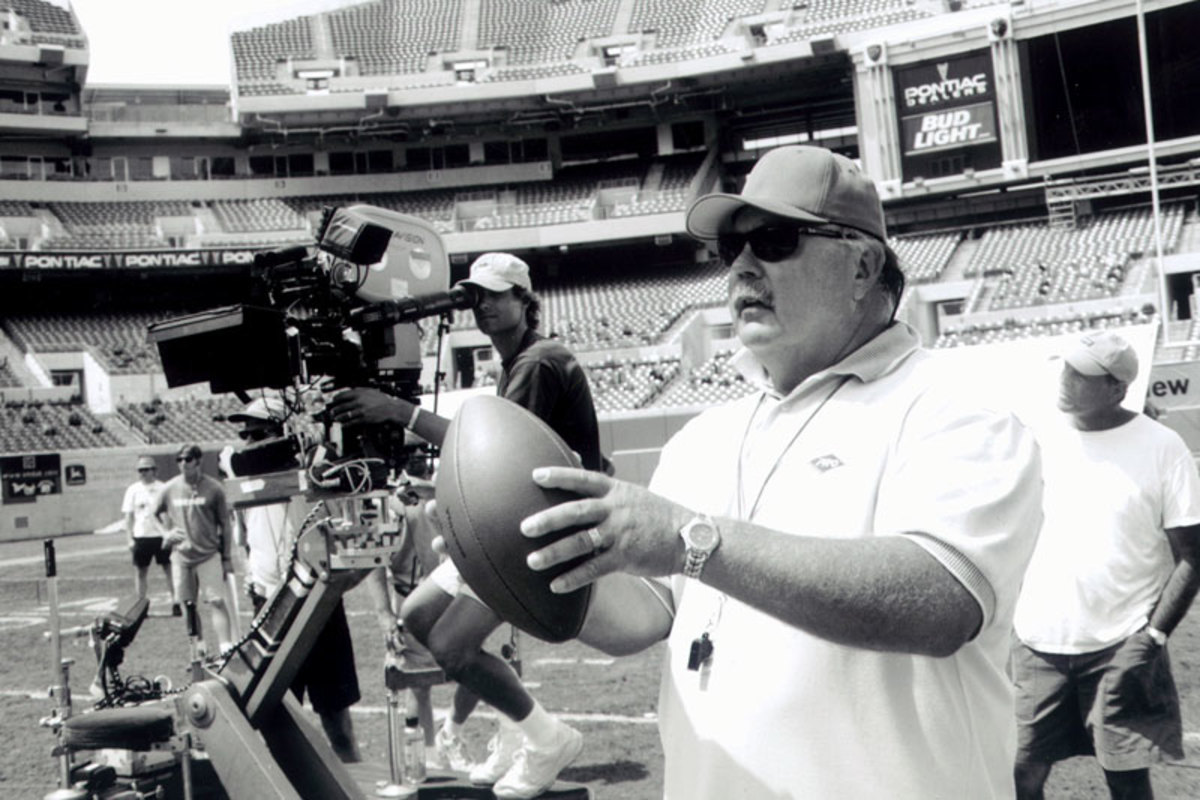

Allan Graf, a former USC offensive lineman who coordinates football scenes in movies, has helped up the realism in big-screen gridiron action. (Ron Phillips)

Graf (61) with his USC teammates in 1972. (Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated)

Allan Graf stands between aspiring football actors and screens silver, large and small. His IMDB page reads like a history of football movies. His credits include Any Given Sunday, Friday Night Lights, The Waterboy, Jerry Maguire, The Replacements, and, most recently, When the Game Stands Tall, along with more than 400 football commercials.

Graf was a starting guard on USC’s undefeated 1972 national championship team, and he later became a stuntman, sliding cars and falling from great heights. He doubled Dick Butkus in Gus, a movie about a mule that kicks field goals. Back then, the “football” in football movies looked little like what unfolded on Sunday afternoons. That’s how Graf’s workload increased. “They knew I wasn’t some Hollywood Jabroni,” he says. “I actually played football. That’s why everyone calls me Coach.”

As the person who coordinated football sequences, he helped push the industry toward realism. He hired a staffer from NFL Films. He researched the time periods for specific movies like The Express, about Syracuse running back Ernie Davis in the late 1950s and early 1960s, to find the right helmets, uniforms, pads and cleats. He used motorcycle cameras to capture the speed and violence.

“Realism is the thing now,” Michael Fisher says. “They want raw, in-your-face football.”

Such verisimilitude requires more than ex-players who look good in pads. Graf needs guys who can give and take hits. Real hits. “This is fake football, but there’s no way you can fake football,” he says. “Everybody’s all-world when they’re in shorts. My guys have to tackle. They have to block. The only difference is we never tackle the actors.” (The stars—the Jamie Foxxes and Keanu Reeves and Adam Sandlers—are basically like red-jersey-clad quarterbacks in practice.) Graf’s son, Derek, also a former USC lineman, has followed in his dad’s footsteps in Hollywood. He's a stuntman and played an undead clown in Zombieland.

What Allan Graf is to football movies, Michael Fisher is to football commercials: a gatekeeper. He has coordinated hundreds of Nike spots in all sports, worked with Michael Jordan (yes, that one) and LeBron James and Emmitt Smith, filmed in freezing rain and extreme heat and sludge. “Realism is the thing now,” he says. “They want raw, in-your-face, real football.”

Another coordinator, Mazio Royster, says that trend escalated about five years ago. It helps someone like him to find work, because he played at USC and in the NFL—three seasons as a running back with the Bucs—and he understands the game. He thinks the rise in football’s popularity in general is the reason directors demand more realistic shoots. There are more commercials about football than about all the other sports combined. The less time spent on technique, the fewer takes that are required, and the less spots are panned on social media as unrealistic junk. “That’s why I became a coach,” he says. “I live through these guys now.”

* * *

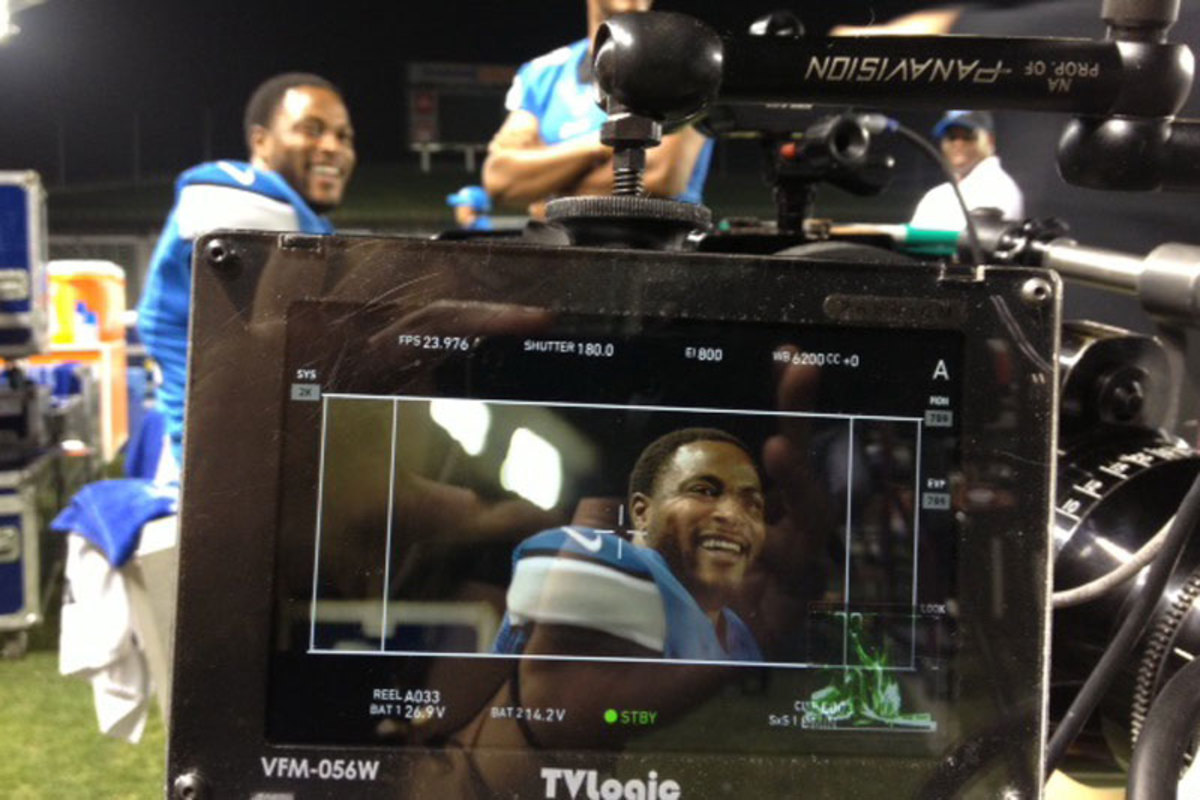

Coordinator Michael Fisher (far left) with Isaiah Mustafa (28, playing Adrian Peterson) and LaMonica Garrett (24) during a Nike shoot in 2009. (Courtesy LaMonica Garrett)

All the football actors want to be Mustafa. He played receiver at Arizona State and tried the NFL, but after practice squad stints with Tennessee, Oakland and Cleveland, he was cut by the Seahawks in 2000. He wanted to act, and he landed a job with Nike. Because of his size—6-3, 215—he could double receivers, running backs and running quarterbacks. He was Michael Vick and Adrian Peterson.

Mustafa did 23 takes for one scene as Peterson’s body double. The director didn’t think it looked real enough. “That’s about as real as it gets,” Mustafa says he told Fisher, the coordinator for that shoot. “I’m getting killed here.” Another time, Mustafa says he took issue with how Graf wanted him to drop back. “You do realize this is fake, right?” Mustafa told him.

Mustafa did maybe 20 football commercials, and he put the extra cash toward acting lessons and his SAG membership. He made between $30,000 and $50,000 annually, which was enough to fund his more serious pursuits. It felt like paying his dues, and the more football commercials he did, the less he wanted to. His shoulder still aches from one job. “I always knew I wanted something more,” he says.

Then he landed that Old Spice campaign. He’s the guy on the horse. Yeah, that one.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=owGykVbfgUE?list=PLB9F260CE56D04E73&w=800&h=450]

Mustafa’s best friend from his football commercial days is LaMonica Garrett, who would go on to a role on Sons of Anarchy and elsewhere. The two actually played football against each other in junior college, but while other football actors held onto their careers with the commercials, Garrett and Mustafa talked about acting and theater and everything but football. They saw football as their way out—of football movies and commercials.

Garrett did Bowflex ads and modeled and even worked for FedEx. He starred in SlamBall, the made-for-TV football/basketball/trampoline mashup. “But I knew where my heart was,” Garrett says. “I knew I wanted to act. You have to change the way these directors look at you. Then I saw Isaiah make it. I’m like, He did it. I can do it.”

I’m Not Russell Wilson, But I Play Him on TV

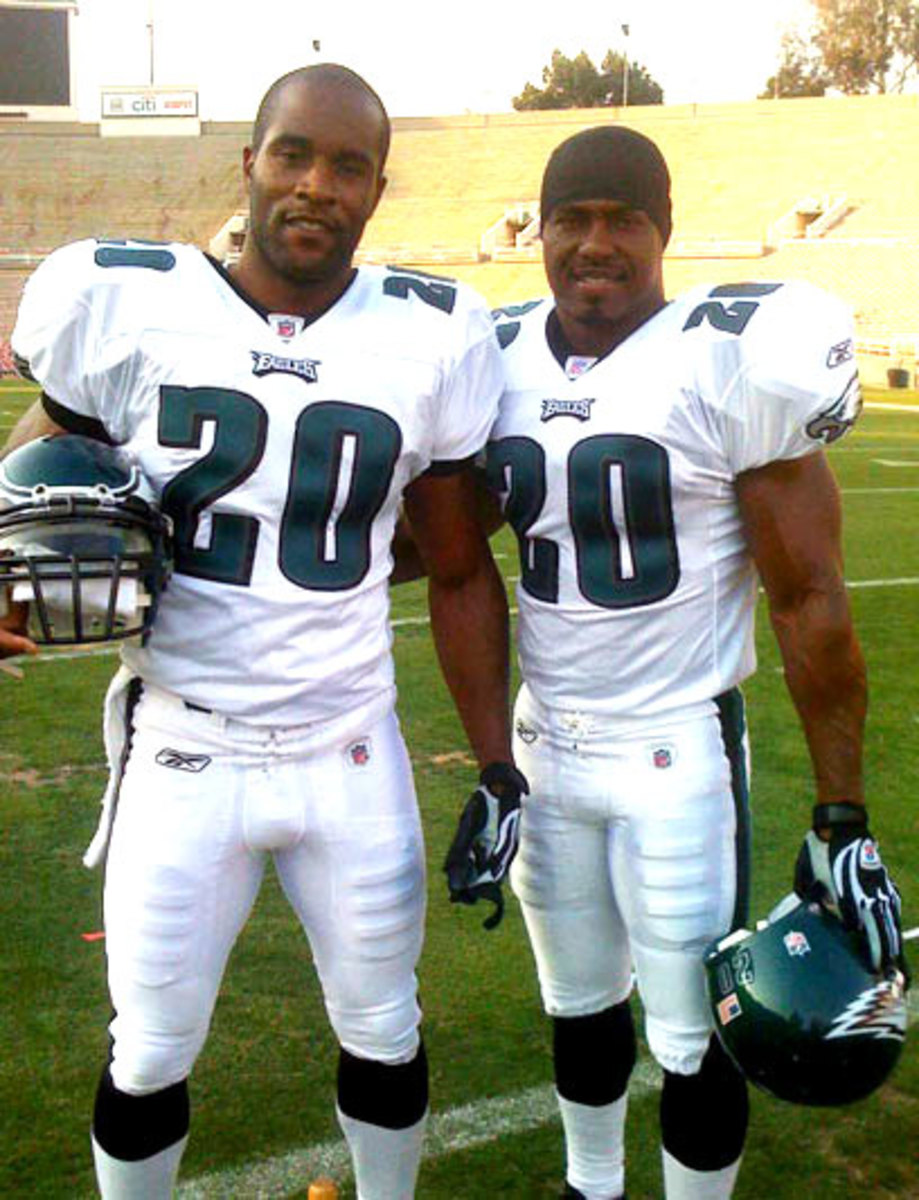

LaMonica Garrett with Brian Dawkins. (Courtesy LaMonica Garrett)

Garrett as Deputy Sheriff Cane in “Sons of Anarchy.” (Prashant Gupta/FX)

Garrett was the star of the trampoline-basketball hybrid “Slamball.” (Robert Mora/Getty Images)

Their advice: To break into acting, ex-players must treat acting seriously, as a craft; they must study, refine, apprentice; they cannot expect for their break to come in a year or even in five. Garrett bumped into Thomas Jones, the former NFL running back, at an audition recently. Jones told Garrett he loves him in Sons of Anarchy. Garrett looked at Jones, once the seventh pick in the NFL draft and still sporting those huge biceps. He figures it’s harder for someone like Jones to make it, because, he says, “Your ego takes a hit. You have to check it at the door. You have to be willing to learn from scratch.

Still, he says, “Now that my career has taken off, I miss the locker room, I miss those guys. Maybe I’ll call Fisher. Tell him I just want to be one of the guys again. Want those sweaty, musty locker room pads. I miss all of that.”

Sometimes Mustafa will catch a football commercial on television. That used to be him, but he often doesn’t recognize the ex-players turned actors who have taken his place.

That’s the other similarity to real football. The roster churns. There’s always a next actor up.

Follow The MMQB on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]