‘Everything You’d Want for a Franchise, This Man Represented’

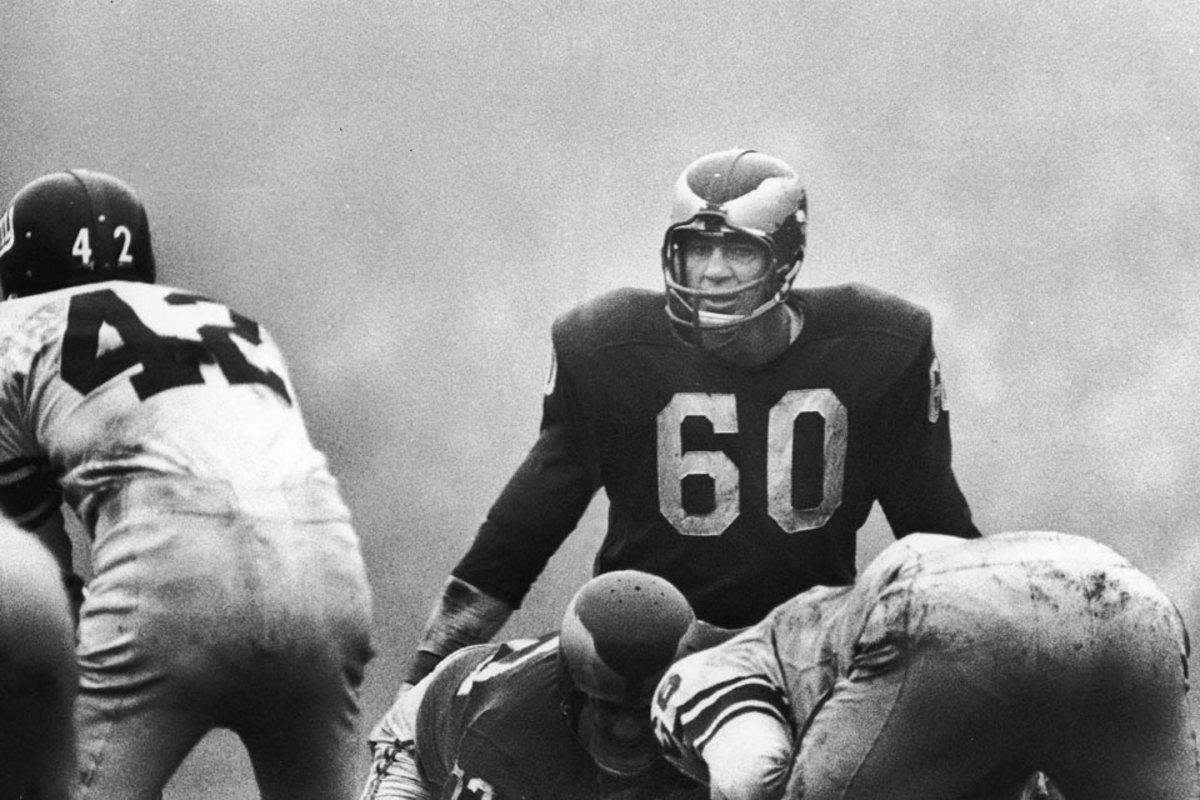

BETHLEHEM, Pa. — They will bury Chuck Bednarik in his Hall of Fame blazer and a bolo tie with a pendant of an Eagle spreading its wings. They will bury the Philadelphia 60-minute man exactly as he was remembered, with hands that looked like gnarled tree limbs and a face distinguished by a razor-sharp jawline and a slight smirk.

On Thursday, mourners said goodbye to Bednarik, the NFL’s last great two-way player, who passed away at age 89. At a public wake, in the historic steel town where he was raised, Bednarik lay in an extra-long casket. A bouquet from the Pro Football Hall of Fame was on display by his feet, a wreath of red roses hung over his heart, and his widow, Emma, a petite blonde with the handshake of a salesman, stood by his side. “It’s been humbling to see how Chuck has touched so many,” she says, her voice calm and earnest. “I think he would have liked to see that.” Everything about the day seemed fitting, right down to the weather: an endless gray sky, unrelenting rain and occasional cool gust swooping in like an unexpected hit.

For nearly seven hours, Emma, her five children, 10 grandchildren and one great-grandchild greeted dear friends, Eagles royalty, and dozens of fans, some in kelly green No. 60 jerseys. A man who named his racehorse “Concrete Charlie” showed up, as did one man who said he attended the iconic 1960 game at Yankee Stadium where Bednarik cemented himself into NFL folklore with a knockout hit on Giants halfback Frank Gifford. Pete Retzlaff and Tommy McDonald, Bednarik’s teammates on the 1960 Eagles, the last Philly team to win an NFL championship, paid their respects, as did the former Eagles coach Dick Vermeil and current owner Jeff Lurie, fresh off a plane from the NFL meetings in Arizona. Lurie, in a suit and flanked by team president Don Smolenski, spoke of Bednarik with superlatives: “Everything you'd want for a franchise, this man represented.”

(Robert Riger/Getty Images)

The son of Slovak immigrants, Bednarik didn’t speak English until he was 6, and had World War II not broken out, he would have joined his father working the open hearth furnaces at Bethlehem Steel. Instead, Bednarik flew 30 bombing missions over Germany as a B-24 waist gunner, then enrolled at Penn and became the No. 1 pick of the 1949 draft. Few uniforms were dirtier than Bednarik’s; he played linebacker and center and virtually every snap, then spent offseasons selling concrete.

The Connell Funeral Home on East Broad Street felt like the center of Bednarik’s Lehigh Valley. The main drag of German colonial homes, antique stores and family-run pizza joints feels quaint, although it is now dotted with super-chain banks, a yoga studio and a cafe serving fair-trade coffee. Across the river you can see the shell of the once-massive steel mill, though the smokestacks are permanently extinguished and now serve as accessories on a 300-room Sands casino.

Throughout the day, cars splashed by and umbrella-doting mourners trickled inside the funeral home. They mingled inside two rooms, both full of collages of Bednarik’s military, football and family life. Among the decorations: a bouquet of white lilies from Bengals owner Mike Brown, representative of Bednarik’s impact in the NFL community. Gifford sent flowers earlier in the week; the Bednarik family was told Broncos quarterback Peyton Manning planned on writing them a letter.

During a speech at the unveiling of his statue at Franklin Field, Bednarik began speaking Slovak. Everyone thought it was profound, says McWilliams, but “actually he was just cursing. He did it to make us laugh.”

While Bednarik has been memorialized as a paragon of old-school football, his toughness rubbed many the wrong way. He was unapologetically profane and held grudges, including one against Lurie—allegedly because Lurie declined to buy 100 copies of Bednarik’s book—that led the Hall of Famer to root against the Eagles for many years.

When he could no longer deliver hits, Bednarik would deliver diatribes about how the sport had changed; how players were soft and overpaid; how few people appreciated the past.

His family remembers Bednarik in a different way: fiery and passionate, yes, but cheeky too. They spent Thursday afternoon telling stories, like the time Bednarik accidentally set off a two-alarm blaze with a fluky leaf blower, or when Andy Reid claimed he feared for his life as Bednarik gave the coach a tour of Philadelphia, driving “100 miles per hour.”

(Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated)

Becky McWilliams, 23, Bednarik’s youngest grandchild, remembers when a 7-foot bronze statue of her grandfather was unveiled at Franklin Field in 2011. During his speech, Bednarik began speaking in Slovak.

“Everyone thought it was so profound,” says McWilliams, now an intern at NFL Films. “Well, he was actually just cursing. Our whole family knew it. I think he did it to make us laugh.”

Another Bednarik secret: He loved music. He was known to come out of the shower and, while still in a towel, play a song on the accordion while dancing with Presleyesque hip thrusts. Bednarik adored polka music and attended countless performances by the Tamburitzans, the famed Eastern European folk music company, all over Pennsylvania.

Bednarik relished it anytime he was recognized in public. “He loved the attention,” McWilliams says. “Because he was really, really proud of his career with the Eagles.” While he was fond of his past—nearly ever inch of his living room was crammed with NFL memorabilia—Bednarik had a complicated relationship with the sport. Most of his grandchildren have never attended Eagles games; Bednarik didn’t watch much football in person or on TV, later in his life. He preferred golf and took pride in making his lawn to look as pristine as a course. He also developed an affinity for reality TV, “especially the trashy stuff,” says granddaughter Lauren Davis, who lived with her grandparents for the past seven years. Among Bednarik’s favorites: “Jerry Springer,” the “Maury Show,” “Cheaters.” “One time my grandma went off to get her hair done, and then errands,” Davis recalls, laughing. “And grandpa goes, ‘That’s it! She’s cheating on me!’ I was like, ‘Grandpa, I think you need to lay off the daytime talk shows.’ ”

Bednarik had a zest for life itself. During one of his missions during the war, he made a pact with God: If you bring me back home alive, I will go to Mass every day. He made good on his promise. “He’d go every single day until he could not drive anymore,” Davis says. “And when he couldn’t go, then he would watch a live stream from home.”

The last few years were difficult. Alzheimer’s began taking his memory; he became forgetful, and sometimes abrasive. In the last few months, he was only a shell of the man they loved. Chuck Bednarik will be buried this week, but everything else about the man—his relentlessness, his complicated politics, his spirited personality—will leave a legacy that is concrete.

(Mel Evans/AP)

Follow The MMQB on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]