The Rivers Rumors

I’ve learned a lot about the passion of football fans in the past couple of days. I’ll explain how, and why, in a couple of paragraphs. But first, I want to weigh in on a story that won’t go away: the future of Philip Rivers with the San Diego Chargers.

I wrote Monday that the Chargers would be crazy to trade Rivers. For the past nine seasons, Rivers has started every one of San Diego's 153 games. He is 92-61 overall, including playoffs, with a 95.7 regular-season passer rating and a plus-130 touchdown-to-interception differential. He will be 33 on opening day. The Chargers are in the horns of a dilemma with Rivers, because he’s entering the last year of his contract and has rebuffed efforts by San Diego GM Tom Telesco to sign an extension. Rivers hasn’t said why, but it seems pretty obvious. He has seven children, is happily married, and is worried about the franchise relocating to Los Angeles.

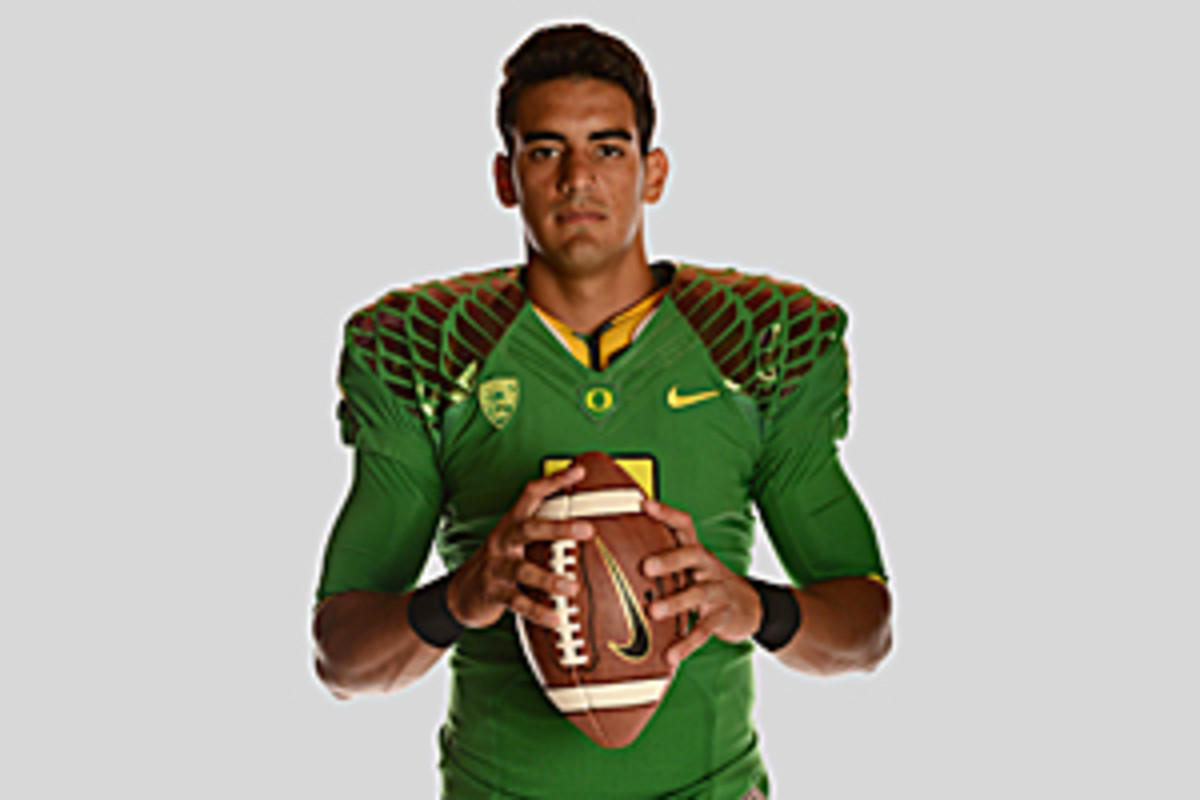

Rivers is from Alabama. He went to college in North Carolina. He’s a homebody type. Nashville is less than two hours from where he grew up. The second pick in the draft is held by Tennessee, and a big contingent of Charger people was in Eugene, Ore., on Tuesday to work out Marcus Mariota. Makes sense: After the Bucs pick Jameis Winston number one—which is the most likely scenario—San Diego could deal Rivers to Tennessee for the second pick in the draft (with other picks thrown in to equalize an odd trade, though I have no clue which side should throw in other picks) and choose Mariota, giving the Chargers their presumptive quarterback of the future.

The Prospects

Marcus Mariota: The Oregon QB’s game is being scrutinized more than any other prospect’s.Michael Bennett: Detailed, inside look at how the Ohio State DT has prepped for the NFL draftNick O’Leary: The grandson of golf legend Jack Nicklaus, the throwback tight end made his own name at Florida State.MORE PROSPECTS

Two and two is being put together all over the planet. Longtime Charger follower Kevin Acee of U-T San Diego wrote this week: “They need to trade Rivers. … This is not for effect. This is best for all involved.” Acee is close to Rivers. Acee is tight with the Chargers. And he’s right that the deal makes sense, but only if one very important condition is met. Only if San Diego coach Mike McCoy and GM Tom Telesco are convinced—not just have a feeling—that Mariota can be a very good long-term quarterback.

Otherwise, I don’t like dealing Rivers. At all. The Chargers haven’t won more than nine games over the past five seasons, but that’s not Rivers’ fault. He’s a 66-percent passer over those five years. He’s had some bad days. Good quarterbacks do. But every year you have Rivers as your leader, you enter the season with a chance to play deep into January. Not to say you couldn’t do that with Mariota eventually, but very likely not right away.

Rivers is healthy. My guess is he’d have five good years left, barring injury. If he’s told the team flat out he won’t go to Los Angeles, then Telesco has to do what he’s got to do. But as of a month ago, Rivers hadn’t said that. All he said was he wasn’t signing long-term—right now. Will he sign with San Diego after the 2015 season? Or would they risk putting the franchise tag on him when he clearly wouldn’t want to be there?

It’s a dilemma. I just know this: Unless Mariota was the object of my dreams, I’d rather have Rivers for one more year and take my chances on him signing one more Chargers contract. If he doesn’t, they can worry about that next March, with a new crop of quarterbacks coming out of college. I’m not a fan of giving away a very good player just because you’re not sure if you can sign him.

A few smart people around football don’t think Telesco will have the stones to deal Rivers. We’ll see. Telesco’s a smart guy. He’ll do what’s best for the franchise. I don’t see how trading Rivers is the best thing, but then again, I don’t know all that Telesco knows right now.

* * *

Before we start with the email, a strong recommendation to read Jenny Vrentas’ story today at The MMQB (and in Sports Illustrated) on the bitter end of Rex Ryan’s reign with the Jets, and his sunny new start in Buffalo.

Now onto your email:

Eagles great Brian Dawkins, who retired in 2011, is one of a glut of game-changing safeties hoping to one day make it to Canton. (Hunter Martin/Getty Images)

Let’s start with your nominations for safeties for the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The response to my Monday column—the crux of which was about the retirement of Troy Polamalu, and how the safety position has been mostly ignored by Pro Football Hall of Fame voters, with only one career safety being enshrined among the last 147 Hall of Famers—was surprising to me. So many of you felt passionately about various names on the safety list. So I opened the floor to you, asking for nominations, and you delivered. I’m using the best ones I received here.

The case for Rodney Harrison, from Nick V.: First safety to ever have 30 sacks and 30 interceptions, ushering in an age of the ‘new’ safety. A physical presence in a defense leading to two Super Bowls, also having the championship-clinching interception in one. Rodney Harrison is the ultimate example of stats not telling the whole story. He wasn’t voted to many Pro Bowls in part because he didn’t get those stats, but also because he was generally viewed as a dirty player. While I’m not going to advocate dirty play, Dick Butkus could be considered a dirty player, Deacon Jones made use of the head slap until banned. There couldn’t be a Hall of Fame without those two players, and there shouldn’t be one without Harrison. He was considered All-Pro twice as many times as he was a Pro Bowler, and I think we can agree which one is the more prestigious accomplishment. Rodney was everything a safety should be. He was a leader in the secondary, could stuff the run, and was an intimidating force that offenses needed to take into account on every down, even if he couldn’t dislodge a ball from a helmet.

The Polamalu Problem

The Pro Football Hall of Fame does not have safety in numbers; only one has been elected in the past 26 years. Troy Polamalu’s retirement shines a glaring spotlight on the issue, Peter King points out as he remembers the Steeler legend’s career (with help from a rival Raven). FULL STORY

The case for Kenny Easley, from Shane: What’s the biggest knock against Kenny Easley getting in? His career lasted seven years, and during those years he was the most dominant, game-changing and fear-inducing safety in the league. The other great safety of his time, Ronnie Lott, feels the same way and has said as much in various interviews over the years. Easley was nominated to five Pro Bowls, was first-team All-Pro three times, was first-team all-decade safety for the ’80s, and was the Defensive Player of the Year in 1984, all while toiling away in the relative anonymity of the Seattle market. The reason his career was cut short was simply due to the reckless abandon with which he played. He fearlessly used his body as a tool to wreak the most havoc possible on opposing offenses during his time on the field, and paid the price for it with kidney disease stemming from his willingness to ingest ridiculous amounts of ibuprofen to stay on the field. Easley’s candle may not have burned the longest, but it burned with a blinding and peerless ferocity. The best way to gauge a player’s value has always been to compare it to his contemporaries of the same era. Kenny Easley was the best. Just ask Ronnie Lott.

The case for Darren Woodson, from Thomas: Darren Woodson was the best defensive player on the best team of the 1990s. He's a three-time Super Bowl winner, three-time All-Pro, and he retired as the all-time leader in tackles for the Dallas Cowboys. Although Woodson might not have the jump-off-the-page stats that voters tend to gravitate towards, if you watched him play, you'd see a safety who could cover slot receivers and play in the box as a linebacker. Not many safeties have that on their résumé. Not many have three Super Bowl wins either.

The case for LeRoy Butler, from Marc: No question the HOF is behind on voting in the safety position. A handful of current and future candidates have similar stats and awards, but the one safety that sticks out to me is LeRoy Butler, who helped transform the safety position into more than just a defensive back. How defensive coordinator Fritz Shurmur used Butler, a four-time first-team All-Pro, on his 1990s Packer defenses modernized the safety position. With Butler, sacks at the safety position became a stat. (He was the first to 20 sacks.) A safety could now play in pass defense, play linebacker position in run defense, cover a tight end or blitz. The NFL Films stuff on Super Bowl XXXII sums up Butler’s abilities. Denver’s Super Bowl offensive game plan revolved around Butler, his capabilities and where he was going to line up. No question other safeties deserve consideration for busts as well, but without Shurmur using Butler to revolutionize the position, the safety isn’t what it is today. Please consider the 1990s all-decade safety and Super Bowl winner for Canton.

The case for Troy Polamalu, from Aaron: While the other safeties identified for enshrinement are each special in their own right, only Polamalu can truly be considered unique. I have often heard of two standards for enshrinement: (1) You cannot tell the story of the NFL without the candidate, and (2) a candidate was so transcendent that a coach could not game plan without taking particular account of the candidate, or simply could not game plan for the candidate at all. Polamalu’s role on behalf of the best defense in the NFL during his time on the team—not to mention Defensive Player of the Years and Super Bowl appearances—meet the first test. As for the second, Polamalu redefined the test itself. The QB always had to know where Polamalu was, as Joe Flacco admitted. (Polamalu’s strip-sack of Flacco in the December 2010 game also proved this point. HOW COULD HE MISS HIM? HE'S THE GUY WEARING "43" WITH THE HAIR!) But even more than that: Some coaches explained that the only way to know where Polamalu might be going was to completely ignore him and focus on the other 10 defenders. Only once the QB grasped the apparent gaps could the QB hope to figure out where Polamalu might end up. And good luck with that.

The Art of Picking Late

No pick in the top 10? No problem. Roster architects from two of the NFL’s most consistently successful franchises—Pittsburgh general manager Kevin Colbert and Baltimore assistant GM Eric DeCosta—share insights into their draft-day strategies for picking late in Round 1. FULL STORY

The case for Brian Dawkins, from Mark: As you mentioned, very few safeties have made it into the Hall of Fame. I believe that this is because many people in the past, regardless of statistics, saw the safety position as one that did not make an impact. Consider the term ‘safety.’ Reactionary.There only if needed. And perhaps this was true. In recent years the perception and the reality has changed. Witness Ed Reed and Troy Polamalu. And Brian Dawkins was the safety that more than any other stimulated this change. He was the engine that made Jim Johnson’s unique and esoteric defenses go; his skills and his play enabled Johnson’s freedom in schemes and blitzes, and made everyone else better. Dawkins could do it all—play in the box, blitz from the corner, cover man-to-man and cause fumbles. I never saw anyone better at causing fumbles. The stats on their own are on a par with the other great safeties, in my opinion. Add to this his consistency, the fact that he could do anything and everything asked of him, his beloved status on and off the field (to me as a fan this is important), and he is a sure Hall of Famer.

The case for Steve Atwater, from Lucas: Despite being a lifelong Cowboys fan, I have to go with Steve Atwater. From 1989 to ’99, no safety had more Pro Bowl selections than the Broncos legend, and only Deion Sanders and Rod Woodson matched Atwater’s eight nods among defensive backs. An absolute tank for his era in the secondary, the Arkansas product was responsible for some of the biggest hits of the ’90s, including a brick wall stop of Christian Okoye, the ‘Nigerian Nightmare,’ that has been replayed time and again. Later in his career, Atwater transitioned into a leadership role on back-to-back title runs with the Broncos. After his retirement in 1999, Atwater was again honored as a 1990s all-decade performer by the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Among the 22 first-team offense and defense selections, only three are not in the Hall of Fame (Tony Boselli and Kevin Greene being the others). Despite his career lasting 11 seasons, the impact Atwater made on every player he laid out, as well as the two championship teams he helped shepherd, will not be forgotten.

The case for Sean Taylor, from Chris: It seems like a tough case to make for a man who only played just over three and a half seasons in the NFL, but it can easily be made. In 2007 when Sean's life was taken away too soon, he had five interceptions through nine games; Ed Reed, who was regarded as the best free safety in the game in his prime, had five through 11 games. Sean was the type of player who changed the way defenses played. Using him in a single-high look, the Redskins were able to play their strong safety as a fourth linebacker because Sean alone could cover the whole back half of the field. He was the favorite player of Gregg Williams, who has been in the league since 1990. Well-respected football mind Louis Riddick called him “THE greatest player I ever personally scouted.” In his second season he singlehandedly won the Redskins a playoff game with a touchdown return on a fumble. In today’s game Taylor would have been the best. Players like Kam Chancellor say they watch his highlights before every game. Chad Johnson (11 years in the NFL) said he was the player he most feared facing.

Thanks, all, for your contributions. Now for the final few pieces of email this week:

SOLUTION FOR THE HOF LOGJAM. Don't you think it is time for changes in the rules of inducting players to the HOF? With the expansion of the league and changes in roster size, it is only logical that there will eventually be a logjam of players deserving to be in the HOF if only five are selected each year. Once the list is narrowed to 10, it should be a simple yes/no vote with a requirement for the player to receive 75% or more of the vote. The voters should have no limit on how many of the 10 they vote yes. If there are years when more or less than five are inducted, fine. This would change the voting into a situation of, "Should this player be in, yes or no," instead of the current situation of, "Should this player be in instead of that player."

—Michael, Colorado Springs, Colo.

Problems and Solutions

NFL film maven Andy Benoit and college football expert Andy Staples combine their knowledge to peg which prospects fit best with which teams. AFC East | NFC EastAFC North | NFC NorthAFC South | NFC SouthAFC West | NFC West (4.21)

I think that makes a lot of sense, with only one asterisk. That would potentially lower the standards for what it takes. There have been years when I walked into the room the day before the Super Bowl and thought that 11 or 12 of the people on the list of modern candidates deserved enshrinement. Once you start electing more people, in comparison more and more candidates will begin to look like obvious Hall of Famers. I like what Rick Gosselin suggested in my column this week. He suggested one year of addressing the current logjam with 10 modern era candidates being enshrined and 10 senior nominees being enshrined. Maybe this could be done in conjunction with the NFL’s 100-year anniversary. I would be in favor of some sort of one-time cleanup class. I don’t think I would be in favor of electing up to 10 modern-era candidates every year.

WINSTON AND TAMPA. In regards to the comment about Jameis Winston—“He’s ready to be an NFL player on the field. But he’s not ready to be an NFL player off the field.”—so you think his agent is playing with the teams to get his client to a better team? It seems strange to say those things when your job is to sell your client. There must be a reason.

—Ray Ekness, Missoula, Mont.

David Cornwell is Winston’s criminal attorney. He is not his agent. I just think it was more a case of the attorney simply being frank and not believing he was saying anything really unusual. There’s no way he was trying to manipulate Winston to get picked by a team other than Tampa. Winston really wants to go to Tampa.

OOOHH, THAT SMELL. You called Lynyrd Skynyrd's “That Smell” one of the worst songs ever created. I urge you to listen again with the proper context, which clearly you don’t know. Ronnie Van Zant was inspired to write the song as a warning about the consequences of careless overuse of drugs and alcohol. Van Zant said, “I had a creepy feeling things were going against us, so I thought I'd write a morbid song [as a warning].” The lyrics cautioned that “tomorrow might not be here for you,” and that “the smell of death surrounds you.” Three days after the album was released, the band was devastated by a plane crash that killed several members, including Van Zant.

—Grant, Minneapolis

Thanks for the interpretation and clarification. But I don’t understand what possible connection there is about substance abuse by band members and a plane crash, unless the plane was being piloted by someone under the influence. I heard from a lot of Lynyrd Skynyrd fans, and I have respect for why the song was written. I didn’t know the meaning of the song. All I knew that is the words I listened to over the years didn’t seem to make any sense to me, and the song itself never appealed to me musically. We all have opinions about different songs. That’s never been on the list of my top 10,000.

Follow The MMQB on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]