My Big Fat NFL Career

SAN DIEGO — It’s a typical Friday afternoon in Southern California. A man with spiked blonde hair and sun splashed across his pale complexion walks into an organic salad joint, his gray T-shirt tightly hugging his toned and tattooed arms. As he surveys the menu, he feels a tap on the shoulder.

“What’s up? How’s it going?”

It’s someone from yoga class. The men exchange warm smiles and chat about the weather, the nearby studio and the neighborhood. Then orders are placed.

“Well,” the tattooed man says, “see you around town.”

“For sure.”

Six months and 85 pounds ago, Nick Hardwick was the center of the San Diego Chargers, tasked with fending off beastly linemen. It’s unclear if the other man knows this, or if he just recognizes the tattooed man from the neighborhood—a guy who otherwise blends in by ordering a kale salad and lemon water.

“It’s kind of crazy,” says Hardwick, his Midwest accent drawn out into a relaxed SoCal cadence. “But this is my life now.”

* * *

This is not the new Nick Hardwick. This is more like the old one.

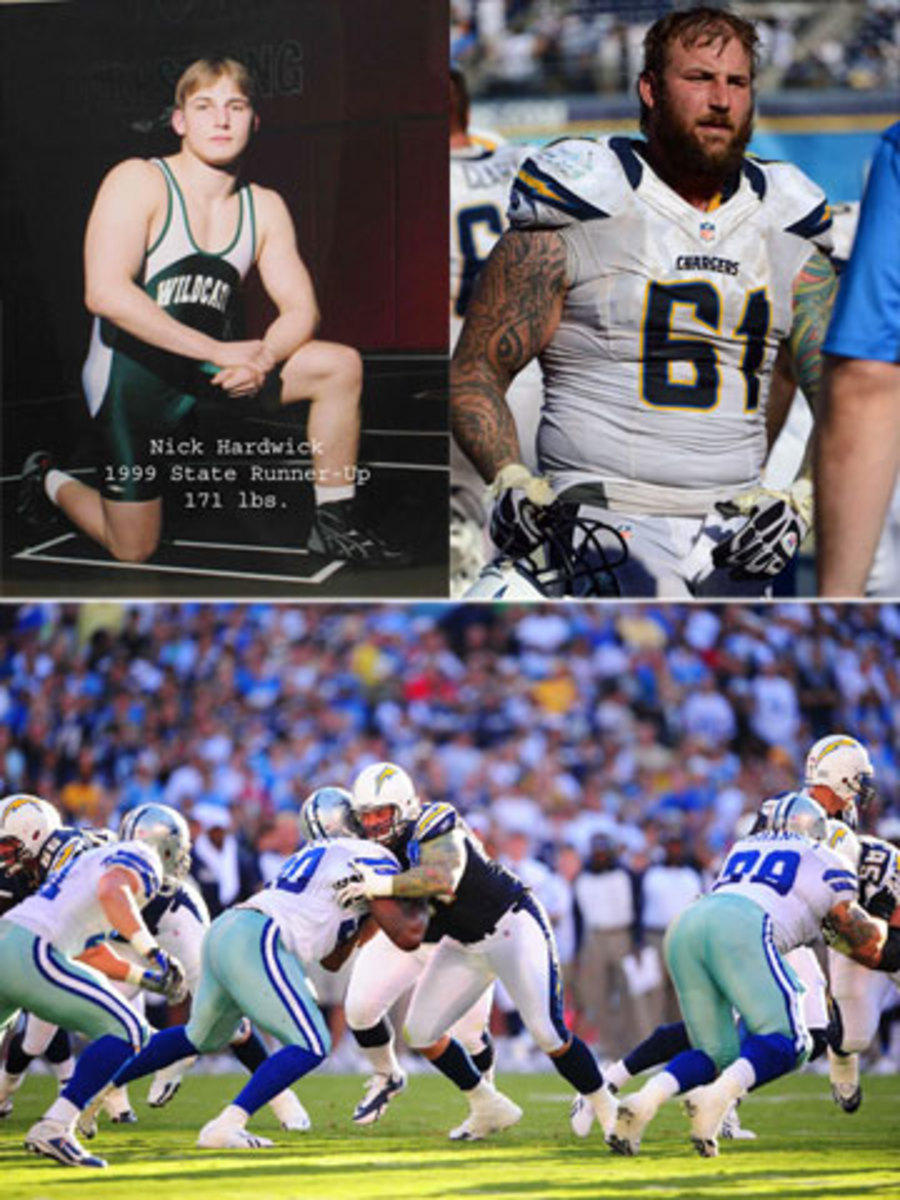

Before he became a 6-4, nearly-300-pound behemoth taken in the third round of the 2004 draft, he was a standout high school wrestler in the 171-pound weight class in Indiana. Hardwick enrolled at Purdue in 1999 on an ROTC scholarship and became obsessed with training to become a Marine—and with unlimited cafeteria pizza. After he bulked up to 230 pounds, friends urged him to go out for the Boilermakers’ football team. Even though he hadn't played football in high school, he made the team and ballooned to 295, packing on muscle and even more fat.

Hardwick wrestled in the 171-pound weight class in high school. (Courtesy and SI photos)

Big 10 football requires a certain body type, so Hardwick would eat a gigantic Jimmy John’s sub for breakfast and another for lunch. At dinner he slathered two pounds of ground beef on multiple tortillas. He consumed a 600- to 700-calorie protein shake before bed—and always set his alarm so he could down another at 3 a.m.

“I’m not naturally a big person,” he says. “So it took a lot of effort for me to sustain that weight.”

In the NFL those efforts were only amplified. During his 4:45 a.m. drive to the Chargers’ facility, he consumed a 600-calorie protein shake and a bar that packed 20 grams of protein. After working out he grabbed a 300-calorie Gatorade protein shake. After showering he hit up the cafeteria to get a large smoothie “with everything imaginable in it”—plus five eggs, sausage, and 32 ounces of whole milk. He would snack on a bag of mixed nuts while watching film. Two or three hours into meetings, he’d down a 700-calorie protein shake. After practice, another protein shake. Lunch in the cafeteria meant a big salad, with as much protein as possible piled on top.

“A lot of bread on the side, too,” Hardwick says.

After even more meetings, Hardwick would go home and eat with his wife, Jayme. Dinner was always a normal meal—meat, potatoes, and vegetables—with normal portion sizes. “I didn’t to drag my wife down with me,” he says. But 90 minutes later the heavy eating resumed. Hardwick would eat cereal poured over a 32-ounce tub of Greek yogurt, the size most people buy to last an entire week.

The nightcap: a pint of Ben of Jerry’s, savored while lying in bed. Karamel Sutra was his favorite, with 1,040 calories, 104 grams of sugar, and plenty of other unsightly numbers that led to even more unsightly numbers on the scale.

Looking at old photos makes him cringe. “I was disgusting,” he says.

* * *

My Big Fat NFL Career

Taking on the Cowboys in a 2010 preseason game. (Robert Beck/Sports Illustrated)

Under center with Philip Rivers on the SI cover in 2010. (Bob Rosato/Sports Illustrated)

Snapping to Drew Brees, 2005. (Rick Stewart/Getty Images)

And that’s Doug Flutie in January 2005. ( John Cordes/Icon SMI)

Leading the way for LaDainian Tomlinson in 2008. (John W. McDonough/Sports Illustratetd)

(Robert Beck/Sports Illustrated :: Peter Read Miller/Sports Illustrated)

Placed on injured reserve with a neck injury early in the 2014 season, his 11th year with the Chargers, Hardwick knew he had reached the end long before his retirement was announced. While everyone around him focused on football, the obsessive personality needed a goal of his own.

“I had been overweight nearly my entire life, and I knew I could get skinny,” he says. “I wanted a magazine six-pack, to look like Brad Pitt in Fight Club. That’s never gonna happen, but I might as well try.”

Hardwick, 33, isn’t the first NFL lineman to drastically alter his waist size after leaving the game. Alan Faneca, Brad Culpepper, Matt Birk, Jeff Saturday and Jordan Gross all made similar changes, and Hardwick was aware of their stories. “They say if you don’t lose the weight right away, you won’t lose it,” Hardwick says. “Coaches say it, guys say it, everyone knows it’s true.”

Hardwick read a lot of nutrition literature and began experimenting. From years of manipulating his weight for wrestling and football, he had a good understanding of how his body would respond. Plus, he no longer had to chug protein shakes.

“I wanted a magazine six-pack, to look like Brad Pitt in Fight Club,” Hardwick says. “I’m no longer carrying all that extra weight. I stand taller. I feel better.”

First, he tried intermittent fasting. Four meals one day, two meals the next, then three, then one. Fifteen pounds melted away during that first week and a half. He eliminated carbs, which helped reduced the water he was retaining, and he began following what he calls a “Paleo-ish” plan. “Whole foods and as much organic as reasonably possible without being a pain in the ass,” he says.

After weaning off the intermittent fasting, Hardwick reintroduced carbs but began structuring carb intake around workouts so he could fuel up afterward. Many meals now look like this: a giant salad topped with a lean meat, two tablespoons of almond butter, mustard, oil, balsamic vinaigrette and hot sauce.

• ALSO ON THE MMQB: What the heck happened to Jordan Gross?

Hardwick picked up yoga—something he wishes he had done throughout his football career—and his weight-room workouts didn’t change except for higher reps with lower intensity. Though he has arthritis throughout his body, he no longer wakes up hurting everywhere. Part of that is because he’s no longer getting hit. “But it’s also because I’m no longer carrying all that extra weight,” he says. “I stand taller. I feel better.”

He began walking up to five or six miles a day. “Me being the obsessive guy I am, I’d also do weird things,” he says. One day he vowed not to sit unless he had to go to the bathroom or get in the car. There was also the time he visited his in-laws in Canada and challenged everyone to a burpee competition in the basement. Another night he wanted to burn off dinner, so he did 500 jumping jacks in his in-law’s driveway. It was an unexpected sight in the middle of the winter. A concerned neighbor called to say, “Uh, there’s some guy jumping around on your property!”

“You want the secret? It’s ultimately this,” Hardwick says, his relaxed demeanor sharpening into the focus of a fitness coach. “Reduce your calories to less than what you burn. Are you disciplined enough to go through this day in and day out?”

* * *

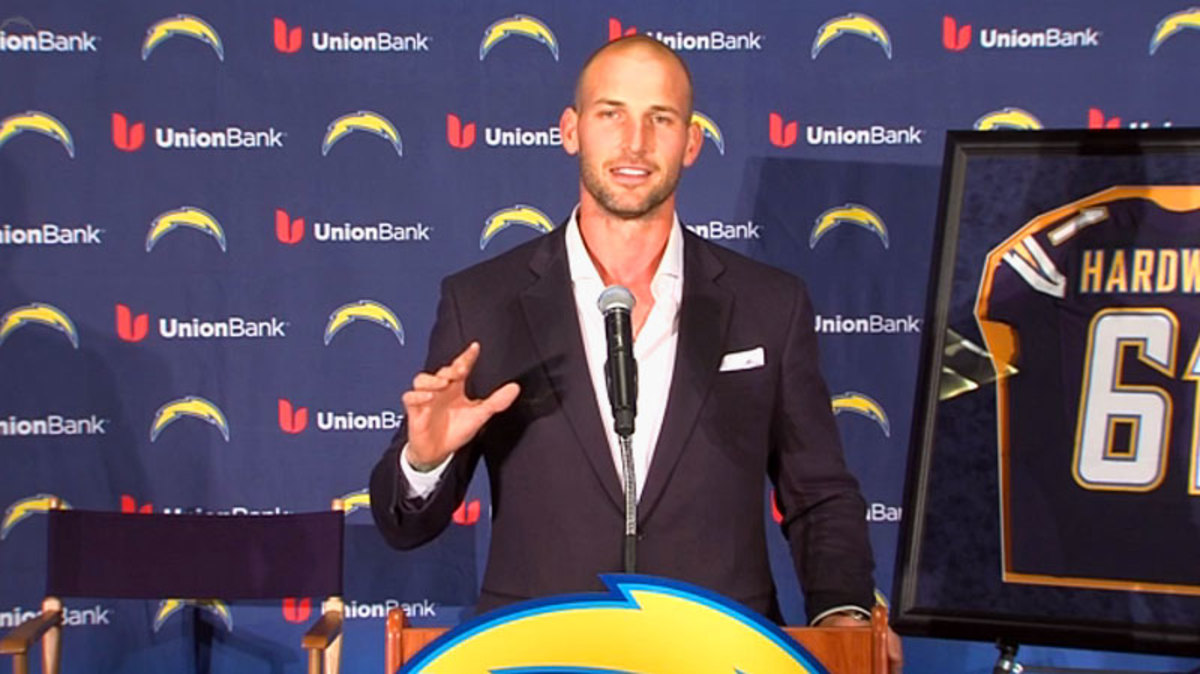

Hardwick at his retirement press conference in February.

Two days after the Patriots beat the Seahawks in Super Bowl XLIX, Nick Hardwick attended what amounted to his football funeral. After 11 seasons with one team, he was entitled to a farewell press conference, and he couldn’t believe so many people showed up. The position he played was inherently thankless, but the offensive lineman was finally being recognized. The newspaper tributes, the calls, texts and media requests were overwhelming. The eulogies were sweet. But one thing really bothered him.

On ESPN’s Pardon the Interruption, Tony Kornheiser commented on Hardwick’s weight loss, saying, “It is eyebrow-raising. It’s a tremendous amount of weight that he has lost in a very short amount of time. and it leads anybody to reasonably conclude that this guy was artificially pumped up like a Perdue chicken. I mean, I understand that they lift a lot of weights in football and they eat a lot of food to maintain their weight, but you have to wonder at some point, with football players and all athletes, if there aren’t performance-enhancing drugs at work here that artificially build them up.”

“That hurt," Hardwick says. "I knew what I went through to get to that point. It wasn’t like I was 300 pounds of muscle before. I had fat on me. Not to mention, I got tested quite frequently. I don’t even know how it’s possible for guys to use steroids in the NFL today.”

“Everyone talks about how hard the transition can be,” Hardwick says of leaving football. “I was in a dark place I thought I was totally incapable of being in ... I had never felt so fragile emotionally.”

Hardwick kept working toward his six-pack, but the farewell glow soon faded. San Diego’s sports talk radio chatter shifted to the draft and Hardwick’s replacement. He stopped getting phone calls and social-media mentions. Football moved on, and he simply faded into the SoCal background.

“I got low, low. I got really low. I had bad thoughts,” Hardwick says. “After the big press conference, maybe a month and a half later, I didn’t want to get out of bed. I wanted to detach from society and go rogue.”

To regroup, Hardwick began focusing on the things most important to him: his sons Hudson, 3, and Ted 1; his wife; a potential career in broadcasting; and his role as a leader in the community. (He’s become active in the Save the Bolts campaign to keep the Chargers in San Diego.)

“Everyone talks about how hard the transition can be, and I thought that couldn’t be me,” he says over the kale salad. “I was in a dark place I thought I was totally incapable of being in. It’s a paradigm shift; it’s a hormonal shift. You’re not going out there and hitting people every day, releasing the same adrenal glands. You’re a mess.... I wouldn’t say I considered suicide. Ultimately, I'd say I had a nervous breakdown and felt quite vulnerable for some time afterwards. I had never felt so fragile emotionally. Thankfully and luckily I have an amazing wife to support me as I go through the transformation process. But by no means do I assume I've arrived in Happyville. I'm sure there are more troughs ahead to work through.”

Hardwick has normalized at 225 pounds, roughly his weight when he joined the football team at Purdue. He wants to help other NFL players transition into retirement. There were so many resources to help him become a football player, he says, but so few about becoming an ex-football player. He belongs to a group of former Chargers who call themselves the “Has-beens.” They meet once a month in San Diego and talk about what they’re going through, the good and the bad.

“It’s hard to get to guys,” Hardwick says. “The NFL doesn’t do a good job of it. It’s up to us on our own.”

As he gets up to leave the salad joint, the busboy comes running over.

“Mr. Hardwick! Mr. Hardwick! Do you mind taking a photo?” he asks. “I was always a big fan of you, and what I respected the most was you always represented the community. You are dedicated to the team and to keeping it here in San Diego.”

The tattooed man with spiked blonde hair smiles.

“Oh, and by the way,” the busboy says. “You look great.”

Follow The MMQB on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]