Why a Pit Crew Looks a Lot Like a Football Team

CONCORD, N.C.—Before the most popular racecar driver in America called him a teammate, before the rumbling of stock cars and the roaring of tens of thousands of NASCAR fans filled his ears on weekends, all William Harrell could hear was the ticking. The clock on his football life was about to strike triple zero.

This was in the spring of 2013, after Harrell, 25, had devoted a lifetime to the game and defied every expectation. A standout defensive end at Hale County High in the small west central Alabama town of Moundville, Harrell had passed on offers from Memphis and Western Alabama to walk on with Nick Saban’s Crimson Tide. Looking back, that final whistle probably should’ve blown the moment the 6-foot, 213-pound Harrell set foot on the Tuscaloosa campus. “At a school like that,” he says, “you’re not a necessity. Day one I walked on, I want to say there were around 40-something guys. Every day after that, I watched them drop like flies.”

How Harrell wound up the last man standing is a testament to the hard work he put in and the nagging feeling that he could always put in more. Eventually he settled into a niche as middle linebacker, excelling on special teams, as a tutor to underclassmen and as a scout team player. In the run-up to the 2012 national championship game he was charged with impersonating Notre Dame’s Manti Te’o—a bit of trivia that could well serve as a litmus test for Bama fandom. Ask Harrell how many SEC and BCS titles he won during his time in Tuscaloosa, from the 2009 through the ’12 seasons, and he will roll back his shirtsleeves and proudly flex tattoos of the five diamond-encrusted rings on his biceps. The last bauble was etched on after the Tide pummeled the Irish in Sun Life Stadium.

Harrell celebrated Bama’s national title game win over Notre Dame; a few weeks later he was contemplating a new sport. (Damian Strohmeyer/Sports Illustrated)

The ink, which is fitting for a guy who’s better known by his middle name, “Rowdy,” after the character Clint Eastwood played in Rawhide, definitely catches the eye. But there’s a reason it escaped the notice of pro football talent evaluators as Harrell was wrapping up his college career. Most wrote him off as too small and too slow to hack it at the next level.

And Harrell had pretty much conceded the scouts’ take. The best-case scenario he had envisioned for his immediate life after football was landing work as a strength coach, a trade he’d spent the tail end of his playing career studying under Bama conditioning coach Scott Cochran. “I still didn’t really know what I was going to do or if I was going to get a job doing that or what,” Harrell says. His sense of uncertainty deepened when Cochran sat him down and asked him if he’d be open to considering a career in … NASCAR? Harrell’s reaction: Doing what?

* * *

Cochran, Bama’s strength coach, has helped players make the transition to NASCAR. (Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated)

It was a fair question. NASCAR, after all, isn’t any easier to break into than the NFL. Harrell was not a driver, not an engineer, not a deep pocketed patron with the resources to put together a team or—failing that—to advertise himself on someone else’s car. Harrell didn’t need a BS in education—which, incidentally, he had just earned that spring—to know that stock car racing was not the sport for him.

Still, Cochran and Saban thought he might find a niche, just as he had in Tuscaloosa. They recommended him to Chris Burkey, an emissary from Hendrick Motorsports, one of NASCAR’s top teams, whom they knew from a past work life. Burkey coaches the band of brothers that hurdles the wall and services a car throughout a race, that braves the ever-present threat of being run over or set ablaze: the pit crew.

How many people does it take to change a NASCAR vehicle? Six: one to prop up the car, one to top her off, two to change the tires and two more to deliver the fresh rubber and remove the spent wheels. An ideal stop lasts around 12 seconds, or about as long as the average football play.

Why the rush? Because just as in football, every second on the track counts—for about 61 meters of position, according to David P. Ferguson, a researcher at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston with a deep curiosity about motorsports. That distance, he posits in a 2015 paper he co-wrote in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning called “Optimizing the Physical Conditioning of the NASCAR Sprint Cup Pit Crew Athlete,” is often the difference between finishing a race first or 10th.

Put another way: The pit crew is essentially a NASCAR special-teams unit, able to swing the outcome on field position alone. In fact, pit stops have exerted such an influence on races that, this season, NASCAR introduced an NFL-style video monitoring system to police crews and their cars more closely. It shouldn’t be much longer now before these men who don helmets and firesuits and move about in a blur are completely stripped of their cloak of anonymity.

Based on the rave reviews Harrell received from Saban and Cochran, which strained to note—you guessed it—the linebacker’s big motor, Burkey thought Harrell could be a difference-maker. The pit coach encouraged the football player to come out for a summer combine at Hendrick headquarters in Concord. “Look,” Harrell told Burkey, “I couldn’t change anything on the car if you asked me to. I’m not a mechanic by any stretch of the imagination.”

“That’s what I want,” Burkey told Harrell. “Come in with a blank slate, and we’ll mold you.”

In Concord, Harrell found the scene to be quite similar to the one at his walk-ons in Tuscaloosa: about 40 or so football types, all of them possessing a particular kind of athleticism—the kind that needs ferreting out. The vetting process, too, was familiar. There were shuttle drills, jump measurements, a bench-press station—obstacles Harrell knew how to navigate.

Harrell (left) earned a spot on one of Hendrick’s four Sprint Cup crews—the big leagues—for 2015. (Courtesy Hendrick Motorsports)

The difference in the case of these tests was that Harrell’s results (which were strong) didn’t so much reinforce the position he would play as determine it. His raw strength (as measured in the bench press) and explosive power (as measured in the jumps) pegged him for a tire carrier, a position that calls for lugging around 80-pound Goodyear slicks.

After a subsequent interview and another tryout—one that actually incorporated a car this time—Burkey offered Harrell a two-year contract with a third-year option, effectively starting in the 2014 season. Optimistically, he’d watch and learn the first year, wet his feet in year two and become a gainful contributor by the end of term at the sport’s highest level, on one of Hendrick’s four Sprint Cup teams: Jeff Gordon, Jimmie Johnson, Dale Earnhardt Jr., and Kasey Kahne.

In every sense, it was a competitive offer. Yet Harrell had his doubts. “I debated it for a while,” he says. “I talked to a lot of people about moving up to Concord. That was a huge move for me. I’d never had to leave Alabama. I was balancing whether it was worth it, and whether I was going to be good at it. I had no idea what I was getting into.”

* * *

What Harrell was getting into was one of the best-kept secret careers in pro sports, something any overachieving athlete transitioning out of college would be foolish not to explore. Along with a competitive salary (top service members bank upwards of $100,000 a year), a career as a tire carrier offers the potential for real professional growth—something the NFL explicitly does not promise with every reminder of the average player’s shelf life: just 3½-years.

A pit crew athlete? He can keep his job for as long as he can beat the clock. For the mean that’s five years. For the exceptional that can be 15 years or more. And when he can’t beat the clock anymore, or wearies of the 36 weeks of travel and 49 weeks of constant aerobic and strength training, he’s well positioned to segue into a slower gig inside the race shop, helping to build racecars from the ground up.

• Also on The MMQB: Read more about former players in our After Football series

When presented this information, Harrell adjourned his internal debate and accepted Burkey’s offer. Before he could appreciate the fact that he was just one of six to make the final cut and now part of an elite group of 24, he second-guessed himself. “I wondered what I was doing here for the first three months,” Harrell says. “It was really, really tough. You don’t grow up learning how to carry a tire.”

Still, if four years as a walk-on in a Saban-run program taught Harrell anything, it was how to compete against his betters. Immediately he singled out the most competent person at his position, a racing lifer named Clay Robinson who toted rubber for the Hendrick team fronted by Earnhardt Jr., the Dallas Cowboys of racing drivers, and studied his every move. Harrell availed himself of the terabytes of race and practice video at Hendrick HQ, from the bird’s eye perspectives to the helmet cam views. Sometimes he watched from his coach’s office, other times right on his smartphone. “I studied [Robinson’s] tendencies,” he says. “I watched film tirelessly, over and over. That’s what I’ve always done to get better. I have to watch myself do it, watch somebody else do, and then compare.”

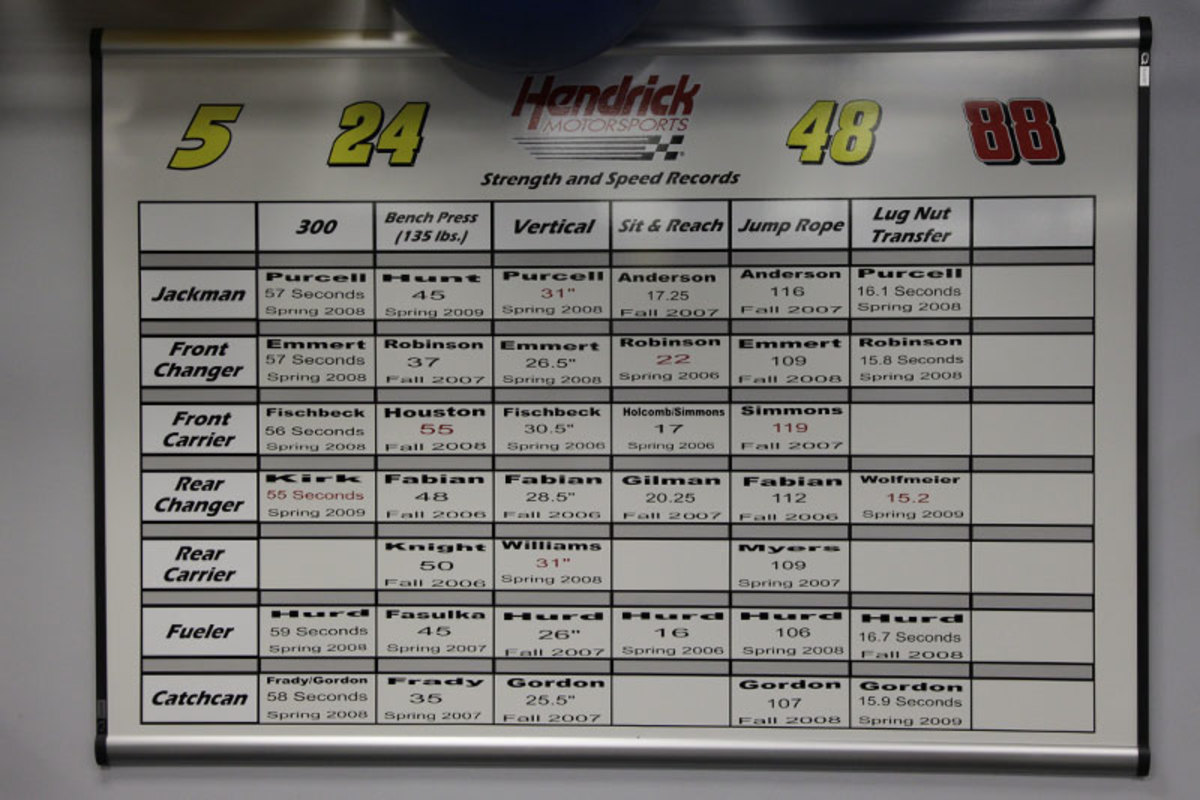

In Hendrick’s training facility (seen here in 2009), stats are kept for performance in various drills. (Michael J. LeBrecht II/1Deuce3 Photography/Sports Illustrated)

He obsessed over the number of steps he took to get back and forth around the aft of the car, with its spoiler jutting out like the arm of a would-be tackler. He strived for a parallel efficiency in the way he handled the tire and slotted it flush onto the wheelbase, allowing the tire changer to bolt it on easily with his air gun. Before he knew it, he found himself possessing a single ambition: to make it to the majors—the Cup series, where Hendrick crews have consistently proven to be the fastest.

After a thorough audit of the position, including a 2014 season as Robinson’s behind-the-wall go-fer and as a Hendrick carrier one rung down in NASCAR’s Xfinity series, Harrell says, “It got to the point where I not only felt that I could compete at the Cup level, but a lot of people around me did.” His opportunity finally came at the end of the 2014 season, when Hendrick lost one of its starting rear tire carriers—Matt VerMeer, a former Division III wide receiver—to another top-flight franchise run by Pro Football Hall of Fame coach Joe Gibbs. In yet another tryout, Harrell was pitted against a Hendrick carrier who had been at it for a decade.

It was your classic position battle, a protracted exercise in precision under pressure. And naturally, while all that waged on, Hendrick held separate auditions for potential free agents. Ultimately, Harrell performed well enough to earn the starting tire carrier job for the ’15 season on Earnhardt’s No. 88 car. The ex-linebacker was gobsmacked. “I had a lot of mental and emotional things going on,” Harrell says. “You never see somebody come in and do that after their first year. Usually there’s a long learning curve. But I just knew if I could go out there and not slack up at all, I’d get my chance eventually.”

Burkey, meanwhile, saw the potential years ago.

* * *

Like Harrell, Burkey, 45, came to the track from the gridiron. An offensive positions coach at Wingate, Tennessee Tech and North Carolina, Burkey left the college ranks in 2005 to become a scout with the Miami Dolphins. He worked for three coaches—Saban in ’05 and ’06, Cam Cameron in ’07 (a 1-15 disaster) and Tony Sparano (and, by extension, team vice president Bill Parcells) in ’08.

During his brief time as a pro football talent evaluator, Burkey never knew the personal satisfaction that drives every scout, which is to say he never bagged a truly brag-worthy prospect. “There were several that I brought in that got knocked down,” Burkey says with a chuckle. Among the rejects was a 5-10, 180-pound rookie free-agent kicker out of Central Florida named Matt Prater whom the Dolphins had claimed on waivers from the Falcons and added to their practice squad in the fall of 2007.

“I said, ‘This kid’s got a fantastic leg. And he can probably kick one day in this league,’ ” Burkey recalls saying to Dolphins brass, to no avail. Prater lasted in South Beach for all of a month before the Broncos signed him away. “And then, of course, he goes on to kick a 64-yarder and break the distance record.

“The thing that was different for us was it was all collaborative. On the pro [scouting] side, we had guys that we’d bring in and we’d want but we’d all have to agree on who gets to stay.”

After the ’08 season Burkey was let go in a reorganization effort and found himself casting about for a career change. When an opportunity to join Hendrick Motorsports as a pit coach surfaced, he seized it. “I always had that in the back of my mind, a passion for the pit crew,” says Burkey, a lifelong racing fan.

The man who hired Burkey, a former Stanford guard named Andy Papathanassiou, was more than a gridiron sympathizer. He was a motorsports insurgent who in the early ’90s helped turn pit stops from a mechanical exercise into an athletic event, shaving off some six seconds (or almost a quarter mile’s worth of track position) in the process. When Gordon went on to win a staggering 49 races from 1994 through ’99, it didn’t take long before rival teams began ditching their fabricators and mechanics and sending ex-footballers to PIT school—the Mooresville, N.C.-based Performance Instruction Training—for hot-housing.

Papathanassiou, a former guard at Stanford, helped bring a gridiron mentality to the garage back in the ’90s. (George Tiedemann/Sports Illustrated)

When that process proves too slow for teams, which generally won’t carry more than the required six crewmembers per car, they poach from Hendrick’s farm system. As an example, Burkey points to Gibbs’ No. 19 car team of Carl Edwards. Making up half of that squad are former Hendrick prospects Robinson, VerMeer and Kevin Harris, a former Wake Forest tailback who played in the 2007 Orange Bowl. “They came in and just plucked ’em from us,” says Burkey, who has since redesigned rookie contracts to protect his farm system against raids. “We have now started signing our developmental guys to five-year deals so we can reap the return on investment.”

Hendrick’s pit crew training facility would put a few BCS schools to shame. Tucked at the back of its sprawling Concord campus is a purpose-built athletic complex. Among the raft of amenities is a 3,000 square foot weight room, a yoga studio, a regulation-sized field turf plot and a sand pit. For treating the inevitable aches and pains, the team regularly calls on Gene Monahan, the legendary athletic trainer for the New York Yankees.

To keep the complex buzzing, Burkey recruits like crazy. Working in concert with Keith Flynn, a former UNC football walk-on who is now Hendrick’s developmental pit crew director, Burkey shakes his old scouting network for leads. On some race weekends he finds nearby campuses to meet up with coaches and prospects. “I typically will find somebody who knows somebody somewhere,” says Burkey. “And I’ll just go in and start a conversation. It’s five or 10 minutes—‘Hey, keep us in mind if you have a few kids.’ We don’t want the kids that are going to be drafted. We want those tough-nosed kids that might be free-agent type guys, that want to do something athletically and compete.”

* * *

Nissley, who caught passes from Blake Bortles at Central Florida and had a stint with the Falcons, is the latest to try to make the jump to NASCAR. (John Bazemore/AP)

On a cool, drizzly spring morning in Concord, at the deep end of the Hendrick campus, a group of 24 such athletes settles in to do just that. The next race, on the west coast, is some four days away. They’re standing inside a covered pit box in gray and black workout clothes, with helmets and the tools of their respective trades: gas can, air gun and tires galore.

All the while Burkey, bedecked in a black windbreaker jacket and matching slacks, paces among them with a folded sheet of paper in hand. Each time he reads from it—“Four tires, nine gallons!” … “Four tires, 16 gallons!”—a grumble rises in the distance and grows ever louder until a shiny silver stock car wends its way around the parking lot and into the pit box. Each time it comes to a full stop, a new sextet envelopes it in a haze of high-pitched whirs and crunching sounds as nuts fly this way and that.

By the time the nuts and the dust settle, the crew has receded, and Burkey inspects their work. Every so often, he finds a crewmember to pull aside and coach up. The overall vibe, with its frequent stops and starts, would be recognizable to anyone who has slogged through a football practice. The only thing missing is the star driver, not some stand-in, at the wheel—a reality that had long nagged team owner Rick Hendrick. Recently, he asked his drivers to come in once a month to run through practices with their pit crews.

The shakeup is as much about building chemistry on the track as off, an ongoing challenge for pit crews. They exist in an ecosystem apart from the larger race team. Practices unfold in isolation—“like a football team only getting to work with Tom Brady on Sundays,” Burkey says. Gordon, though, has welcomed the chance to get in some extra reps.

When the practice finally ends hours later, after a final huddle is broken, Burkey ducks into an adjacent office building and settles inside a windowless conference room. On a whiteboard are a series of colorful magnet strips bearing the names of all of Hendricks pit crew team members, arranged according by car assignment and depth. If you didn’t know better you’d think you were inside the war room of an NFL team.

Not that everyone on the farm comes directly from the college gridiron. A trio of former Pitt wrestlers—Zac Thomusseit, Matt Wilps and Donnie Tasser, who dabbled in sportswriting after graduation—joined up with Hendrick in 2014. Also in that same class was Adam Nissley. A 6-6, 267-pound blocking tight end who caught passes from Blake Bortles at Central Florida, Nissley, 27, signed as a free agent with the Falcons—after he was passed over in the 2012 NFL draft—expressly to be on the same team with Tony Gonzalez. “The first year was 2012, the year we went all the way to the NFC Championship Game,” he says. “We lost to the 49ers at the dome and were one game short of the Super Bowl.”

The No. 88 car crew. (Courtesy Hendrick Motorsports)

His own NFL run was marked by more downs than ups. Midway through his rookie season he tore the ACL in his left knee during a non-contact practice. Then two preseason games into his second season, he tore his right ACL. “After that,” he says, “I pretty much knew what my future in the NFL was.” The Falcons released him the following spring.

Rather than despair, Nissley embraced the opportunity to explore a dormant career curiosity. “I’d always been kind of enamored by NASCAR pit crews,” he says. “I thought I could get in on a team pretty well as a jackman. It was another way for me to be in the same lifestyle that I've been in for my entire life and be around a competitive environment. That something that really drew me.”

A Falcons teammate of his who had played for Burkey at UNC connected Nissley with the pit coach. By the summer, Nissley was trying out for a spot in Concord. Besides the Pitt wrestlers, he was the only other prospect selected. Now comes the hard part—getting past what Harrell calls the Is my time ever going to come phase, to that cherished Cup assignment. Sure, Harrell can still hear his professional clock ticking. But it will be a while before the final whistle sounds.

Follow The MMQB on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

[widget widget_name="SI Newsletter Widget”]