If You Believe Every Year…

EAST CLEVELAND, OHIO — The stretch of Euclid Ave is mostly barren, dotted by boarded-up storefronts and unmarked Chinese restaurants. Club Dew Drop, a dimly lit bar accessible only by a back entrance, is one of the few establishments with any activity.

There’s a jukebox in the corner—but no music playing—and a stripper pole. The felt of a wobbly pool table is covered in black stains where chewing gum was peeled off and dirt clung to the sticky spots. Tonisha Gorde, a 38-year-old Cleveland native, pours drinks for four men sitting at the bar. One wears a white Paul Warfield jersey, and another has a brown t-shirt with an orange Browns logo across the front. It’s 2 p.m. on a Tuesday in the middle of August.

“It doesn’t matter where you are or what time of year it is,” Gorde says. “If you’re somewhere in Cleveland, you’re always going to find someone who wants to talk about the Browns.”

Indeed Reggie Davis, a 54-year-old out-of-work mechanic, is eager to engage in a conversation about quarterback Josh McCown’s qualities as a leading man, and Danny Shelton’s impact on the Mike Pettine-coached defensive line. He can list the last 15 starting quarterbacks almost without fault (he flubs on Jeff Garcia) and has a ready explanation for why their 7-9 record in 2014 will flip to 9-7 this season (“No more Johnny Manziel circus! McCown is gonna tutor him!”). Gorde tells a story of how her mother almost kicked her out of the house when she came home with her neighbor’s car keys, featuring a Ravens keychain.

“Everybody in this city knows someone like that,” Davis says.

The Browns dominate conversations at any time of year, not unusual for the local team in an NFL city. But it’s a little different here. For five decades, those conversations have included the same talking points: We’ve been through so much heartbreak. There’s so much dysfunction. This city could really rally around a winner. We need a quarterback. Maybe we’re on the right track. Wait until next year.

After a half-century of futility, rife with historic meltdowns, organizational malaise and the franchise at one point packing up and moving to Baltimore, a rabid fan base compulsively harbors hope. It raises the question: Why?

Davis puts down his Miller Lite.

“Because it’s like believing in Santa Claus,” he says. “If you wish every year, and you believe every year, eventually you’ll get what you want.”

* * *

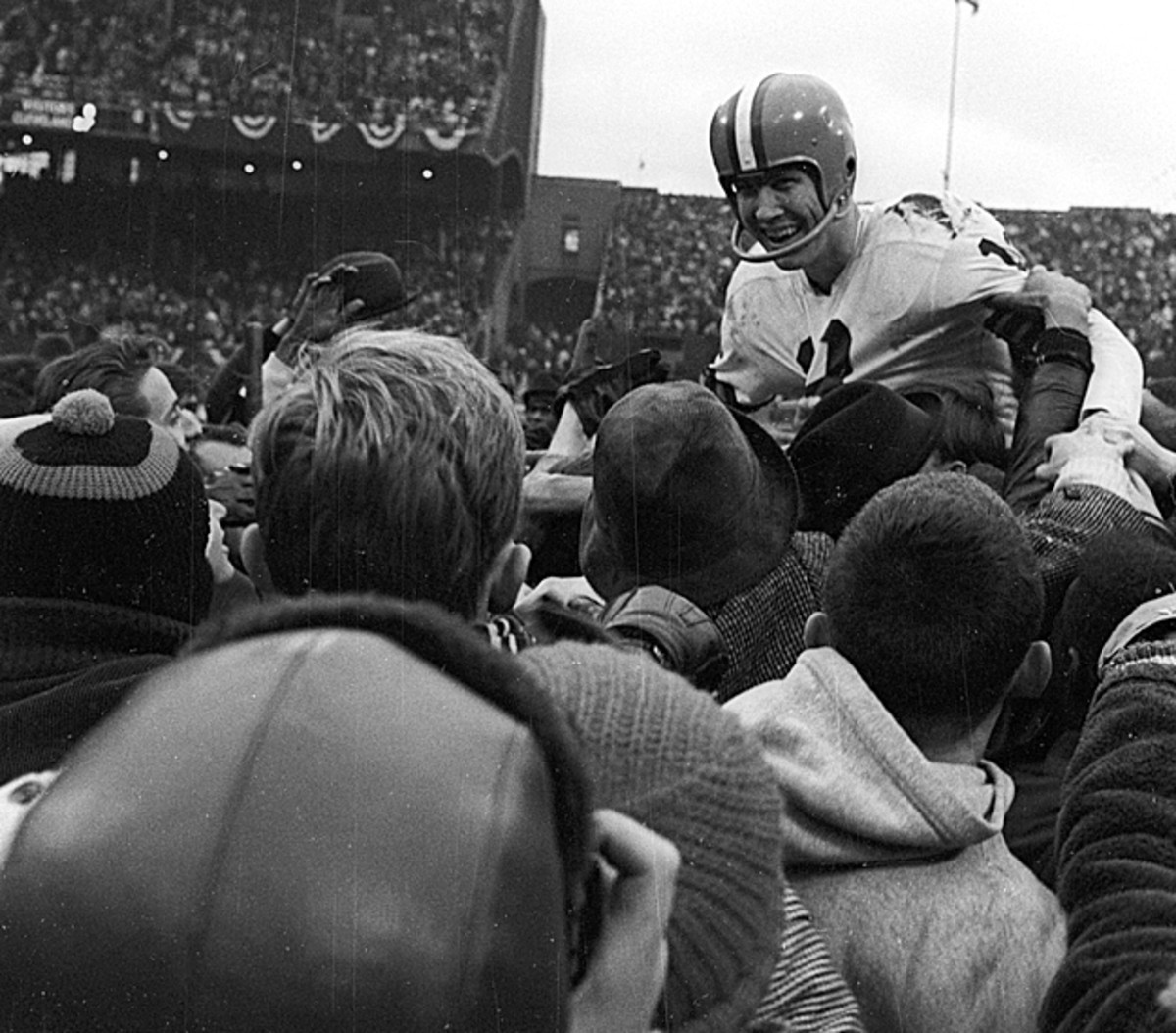

No Cleveland resident younger than 50 knows what it’s like to root for a champion. The last title for any of Cleveland’s major pro sports teams—the Browns, MLB’s Indians and the NBA’s Cavaliers—occurred here, in 1964, at Cleveland Municipal Stadium. As the legend goes, the Browns stayed at the Pick-Carter Hotel before the championship game, and one audacious Colts fan approached Jim Brown and a few teammates at lunch. The fan tried to psych them out by playing taps on his horn. The next day Gary Collins caught three touchdown passes from Frank Ryan and Brown rushed for 114 yards as Cleveland blanked Baltimore, 27-0.

The next 51 years have been a somber procession. Good teams have come and gone, but the bulk of Cleveland’s sports history is undermined by painful moments, each with one-word descriptors: The Drive, The Fumble, The Shot, The Move, The Decision. No U.S. city has weathered such a streak. Since that ’64 title, there have been a combined 142 seasons of futility for the Cleveland three.

The Browns have become cellar dwellers with exceptional flair. In the past two years alone the team has cycled through a new GM, president and coach, saw its new owner subjected to an FBI investigation for fraud and conspiracy, had its general manager suspended for illegally sending texts to the sideline during games, traded a running back they had selected third overall only one year earlier, let its best assistant coach walk away and had its prized receiver suspended for a year. And that list doesn’t even touch a quarterback situation that was a perpetually unsettled before the selection of Johnny Manziel with the 22nd pick of the 2014 draft turned it into a circus.

“Being a Browns fan is like being in a marriage,” says 64-year-old Pat Sumrada, a recent retiree attending training camp wearing a vintage trucker hat celebrating the team’s 1980 AFC Central Division championship. “Sometimes you hate your partner, sometimes they drive you nuts. But you need to stick with them, unconditionally, because that’s the vow you made.”

That’s why the Browns sold out an intrasquad scrimmage at Ohio Stadium in August—60,000 tickets—in less than four hours.

“You feel for these fans,” says offensive tackle Joe Thomas, the No. 3 pick of the 2007 draft and now the longest-tenured Brown. “You see how bad they want it and how much it would mean to them. You feel pressure because you’re not just playing for yourself or your teammates. You’re playing for a city, a region.”

When Thomas was a rookie, he received a piece of advice from wide receiver Joe Jurevicius, a native son of Cleveland playing the final season of his 10-year NFL career: The fans don’t care if you win or lose. Of course they want you to win, but what they care about most is that you bust your ass every day. If you do that, they’ll stand behind you no matter what.

All Thomas has done in his nine seasons: start all 128 games and play in every one of the team’s 7,917 offensive snaps. “Sometimes I wonder,” Thomas says, “if that’s enough.”

* * *

Nearly every Browns fan remembers where they were on January 17, 1988, the day of the AFC title game, just one year and six days removed from John Elway and The Drive at Cleveland Municipal Stadium. Trailing 38-31 in Denver with a little more than a minute to go, Ernest Byner was about to cross the goal line for a game-tying touchdown. Broncos defensive back Jeremiah Castille stripped the ball at the 1, and Denver recovered.

“The Fumble,” gruffs 72-year-old Joseph Wilmer. “I was at my grandparents’ house. I remember my grandfather cursing and my grandmother crying.”

“I was at a friend’s place,” says 61-year-old Larry Tims. “I walked home afterward. I don’t know if I stayed to watch the last down.”

“I remember saying, ‘We’ll get them next year,’” says 64-year-old John Krueck.

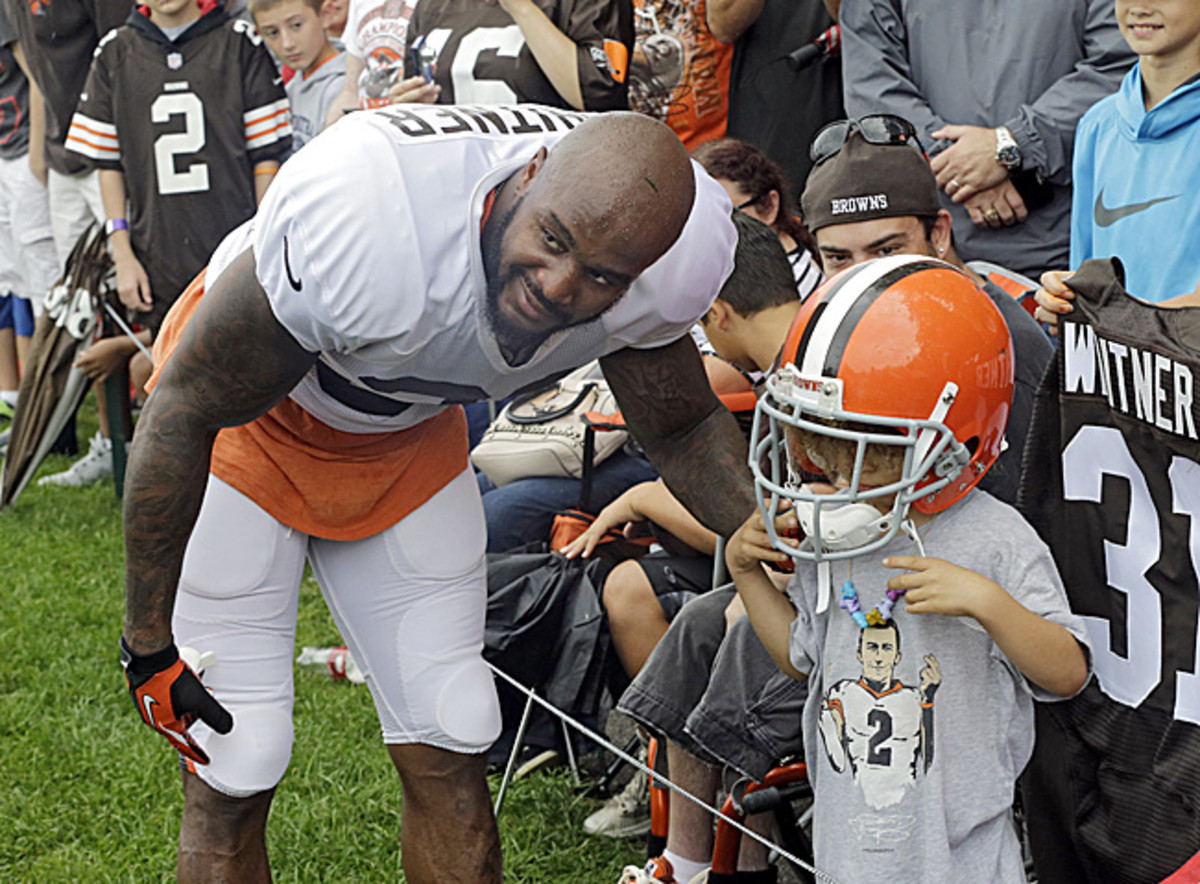

“I was with my family, we had a TV that sat on the floor, with all the knobs on it,” says Donte Whitner, 2 at the time. “I’m told a lot of my family was upset, and a lot of things were broken that night.”

For that reason Whitner, a three-time Pro Bowl safety and Cleveland native who spent his first eight NFL seasons with the Bills and 49ers, signed with the Browns before the 2014 season. Call it a LeBron Complex.

“Not only is my entire family diehard Browns fans, but [so is] everyone I grew up with, dozens of people,” Whitner says. “If I could bring joy to all of those people, many of them who could really use something good…”

Whitner pauses, scanning the sideline at training camp, where hundreds of fans are lined up for autographs. Training camp resembles something of a carnival with a moon bounce, Papa John’s stand with free samples, face-painting stations and cardboard cutouts where fans can take pictures wearing a Hall of Fame jacket.

“I’ve been in a lot of great football cities, but there’s something different here,” Whitner says. “We’re tired of being down in the dumps, we’re tired of being overlooked. We’re tired of being ridiculed and brushed off year after year. That’s why we’re so desperate to win.”

* * *

When LeBron James announced he was returning to the Cavaliers last summer, I was in Cleveland for a Sports Illustrated assignment. I saw euphoria—bars selling $2 LeBron Shots (along with packets of sugar, to be tossed into the air like James’s pregame chalk), playlists heavy on Bon Jovi’s “Who Says You Can’t Go Home,” Eddie Money's “Take Me Home Tonight” and Miranda Lambert’s “The House That Built Me.” But that night, what stood out most was that everywhere I went, hundreds, if not thousands of people were wearing James’s No. 23 jersey. In the aftermath of The Decision, the B-roll of choice showed fans burning those jerseys. But apparently most held on to them, storing them in attics or the backs of drawers, maybe as a piece of nostalgia, but perhaps as a symbol of hope.

“I think it’s hope,” says BanaeSnowden, 54, attending Browns camp with 12 family members to celebrate her granddaughter’s 8th birthday. “This city is about hope and about what could be. And that’s why this city rallies around sports. Sports bring us together, whether you are black or white or whatever. You come together and hope that we will all come out on top. Every year we have a chance, and that’s the beauty of a new season.”

I ask Snowden what she does when she’s not rooting for the Browns. She works, full-time, in security. She’s a loss-prevention agent.

• Questions or comments? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com