Ten years since Katrina: Oral history of the Saints and their Superdome

Ten years ago, storm waters from Hurricane Katrina topped levees designed to protect New Orleans, leaving the city and Gulf Coast region trapped in a cloud of chaos and tragedy. An estimated 1,836 lives were lost. Homes were destroyed en masse.

As New Orleans and its iconic landmarks, like the Superdome, were ravished, the preponderance of local businesses— including a professional football team—had no choice but to relocate.

In an SI.com exclusive oral history, players and executives share their memories from the year of the displaced New Orleans Saints and the miraculous revival of their stadium.

Friday, August 26, 2005: Meteorologists warn citizens in the Gulf States that a major storm is on its way. Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco declares a state of emergency, and the White House begins deploying National Guard troops to the region.

The Saints host the Baltimore Ravens in a preseason tilt in front of a sparse crowd of 44,000. As a precautionary matter, the team leaves for Oakland the next day even though that game isn’t scheduled until the following Thursday. Opinions about the storm’s potential impact vary, though preparations are thorough.

"Everyone who is from Louisiana was used to this every year. No big deal. We thought we'd wait it out and be right back in New Orleans."

Saints vice president of communications Greg Bensel: I grew up in New Orleans with a lot of hurricanes and 95% of the time they veer to the East or the West. As Katrina was making its way, I thought, ‘man, this is a humongous storm and if it stays on the track it’s on, this is going to be bad.’

Saints defensive end Will Smith: We didn’t think it would be severe at all. They were saying it may be a tropical depression or a category 1 or 2. Everyone who is from Louisiana was used to this every year. No big deal. We thought we’d wait it out and be right back in New Orleans.

Saints running back Deuce McAllister: As it got closer, it got stronger but all of the sudden it broke down and decimated as far as its strength. Even though it was a strong storm, it wasn’t a bomb or anything.

Saints general manager Mickey Loomis: We had some hotel rooms outside the city where people could go if they had no place to go. We’re making all these preparations to get the team to California and at the same time give players ample time to make their own arrangements. Or we’d help them evacuate their families.

Doug Thornton, regional vice-president of SMG, the facility management company that oversees the Superdome: There was a lot of anxiety. Fear of the unknown. We had received a call from the city to activate the medical special needs shelter. We used our club lounges for patients whose caregivers had left them or were in nursing homes. They were brought here to ride out the storm. None of us really knew where it would hit.

August 27, 2005: Thornton and SMG must now oversee the Superdome’s transition from house of fandom to house of refuge. Hurricane Katrina winds reach 115 mph and increases to a Level 3 intensity. Local citizens begin to leave New Orleans.

Thornton: We got the call that officials wanted to open the Superdome as a refuge of last resort because they had received a dire warning from the National Weather Service that it was potentially going to be over 18 feet of water and could go overtop the levees.

August 28, 2005: Katrina becomes a Category 5 storm with winds swirling at 160 mph. In the morning, New Orleans mayor Ray Nagin orders a mandatory evacuation of the city. About 14,000 residents unable or unwilling to leave New Orleans take shelter at the Superdome. That number swells to 30,000 in the days that follow.

Thornton: A lot of our employees heeded the Mayor’s orders but we knew there would have to be a number of essential employees that came to the Superdome to keep it running, mainly to man our central plant where the generator is located. We had about 18 employees and we all brought our families. We had about 225 other Superdome workers, inclusive of their families who couldn’t get out before the roads were shut so they came here and we put them to work. It was very tense not knowing how long we’d be here and having very little resources. We didn’t have concession workers so we had to bring boxes and pallets of food up to the plaza and distribute to people one at a time. These folks after day one weren’t sure if it would be their last meal or not.

We kept people confined to the lower level because we had a football game scheduled the next week and we wanted to keep the stadium in tact in case we played it. We didn’t know.

• LAYDEN: How sports have helped New Orleans heal in decade since Katrina

August 29, 2005: In the early hours Category 4 Hurricane Katrina makes landfall. By 8 a.m. the storm eye's passes through New Orleans and the sense is that the city has avoided a catastrophe. But just two hours later, reports surface that levees in the Ninth Ward are overtopped. By late morning, a large section of the 17th Street Canal levee is breached and the city begins to flood.

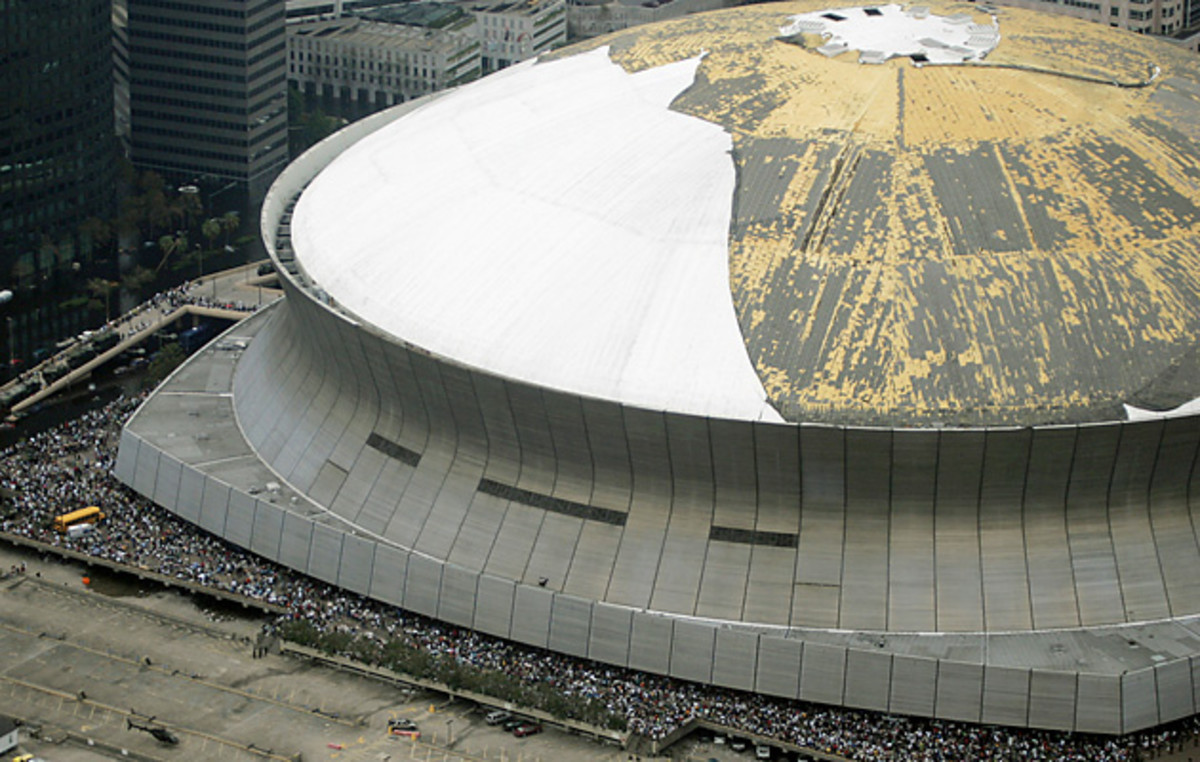

Also that morning, howling winds cause peeling holes in the Superdome’s roof.

"Many came with nothing more than the shirt off their back. They were so thankful to be alive but so fearful about their future. So were we."

Thornton: I was in disbelief. The roof was being peeled like an onion. At the same time it was this great sense of loss. It was like a watching a school yard bully beat up on your best friend and you can’t do anything about it. It keeps pounding away for hours and you just wait for it to stop but it doesn’t stop. It was impossible to believe this was happening before my very eyes to a building that represented such strength in the community.

As we walked across the field we almost tripped over a lightning rod that had fallen from the roof. I was really worried we would have someone killed by falling debris. We moved quickly to get those people to the concourse where they were no longer exposed. By the grace of God we didn’t have any injuries.

People who came here were so helpless. Many came with nothing more than the shirt off their back. They were so thankful to be alive but so fearful about their future. So were we.

The Superdome roof loses 70% of its membrane and multiple sections of the metal gap are ripped apart allowing massive water penetration. Meanwhile, 2,200 miles away from New Orleans, nestled in the safe confines of the Fremont Marriott, the Saints watch the city’s devastation unfold on television.

"All I could think about was getting back there."

McAllister: You think back to the convention center and to different shots of the city and you hope you don’t see anyone you know. That was the one fear.

Bensel: When we saw the Dome, we knew we wouldn’t be back there for a while and we started thinking about contingencies.

New Orleans Saints wide receiver Joe Horn: All I could think about was getting back there. I wanted to set aside my obligations as a player and fulfill my human obligation of trying to help people in the city who loved me.

Cowboys linebacker Scott Fujita: I remember watching the damage from a locker room television in Kansas City. Then I was traded to Dallas and hearing about these refugees and everyone in Dallas was talking about it, saying things like, “Thank god we’re not in New Orleans right now. What a train wreck that place is.”

[pagebreak]

The team enacts on-the-fly contingency plans about the season’s future while juggling personal affairs in the midst of chaos. Some Saints players go back to New Orleans and the surrounding areas to visit various places of refuge in the wake of disaster.

Loomis: I remember one morning I looked at USA Today, there was a picture of a man carrying his belongings and wading through water, and the cross streets in the picture were the cross streets of a house I was building. That’s how I knew the lot there was flooded. It’s hard to maintain a focus of the job when you have so many concerns about friends and family.

Horn: At the Alamodome [in San Antonio, where some were sent] it was like a refugee camp. It was just sad. But when the kids ran up to me I got more excited about playing football.

McAllister: I had an opportunity to go back that Saturday and do stuff for the Red Cross. Even to think we considered these people refugees. They were not refugees; they were people who lost their homes. When someone loses their home in a fire we don’t use that term. These people were American citizens who just lost their homes. To think they could not get help. To think we were responding in the manner we were was really mind-boggling.

The league and the team broker a deal to temporarily relocate to San Antonio where Saints owner Tom Benson is well connected.

Bensel:

Smith: The conditions were horrible. You go from staying in a nice place, having ice tubs and other amenities we’re used to for treatment. It went from like going from the NFL to high school football. I was young at the time and just kept my mouth shut but the leadership tried to express frustrations and a lot of our guys were outspoken. We tried to get Tagliabue to visit right away but he couldn’t make it. By the time he did visit us right before our first game, it didn’t go over well.

The commissioner wound up coming out to meet with the team three or four times and things started getting better, but the initial shock wasn’t good.

Horn: The people of San Antonio treated us really well. But the facility that most NFL teams work on, we had to adjust. We were in a locker room at the Astrodome that was old. The accommodations weren’t what we were used to. The practice facility we were at wasn’t what we needed to prepare ourselves to win football games. They were preparing parades with trombones playing while we were trying to do walk-throughs in a parking lot. It was horrific. The New Orleans Saints season should have been canceled.

Loomis: I thought the conditions were awesome for us. We spent the first 30 days in a hotel. It was makeshift, there’s no question about it, but I didn’t think it was hardship. We need to keep a perspective about what hardship is.

September 5, 2005: Doug Thornton comes back to New Orleans to assess the damage at the Superdome and ascertain its chances of survival. The conditions at the stadium are more dire than when he left.

"There was human waste everywhere. Flies. Mold. Doors were wide open."

Thornton: I had to wear a respirator because the bacteria and of course there was human waste everywhere. Flies. Mold. Doors were wide open.

Within a week, with military passes, we brought in 14 specialists and they crawled through the building with flashlights. It was September 30when we were told the Superdome could be saved but it would cost at least $200 million and take over two years.

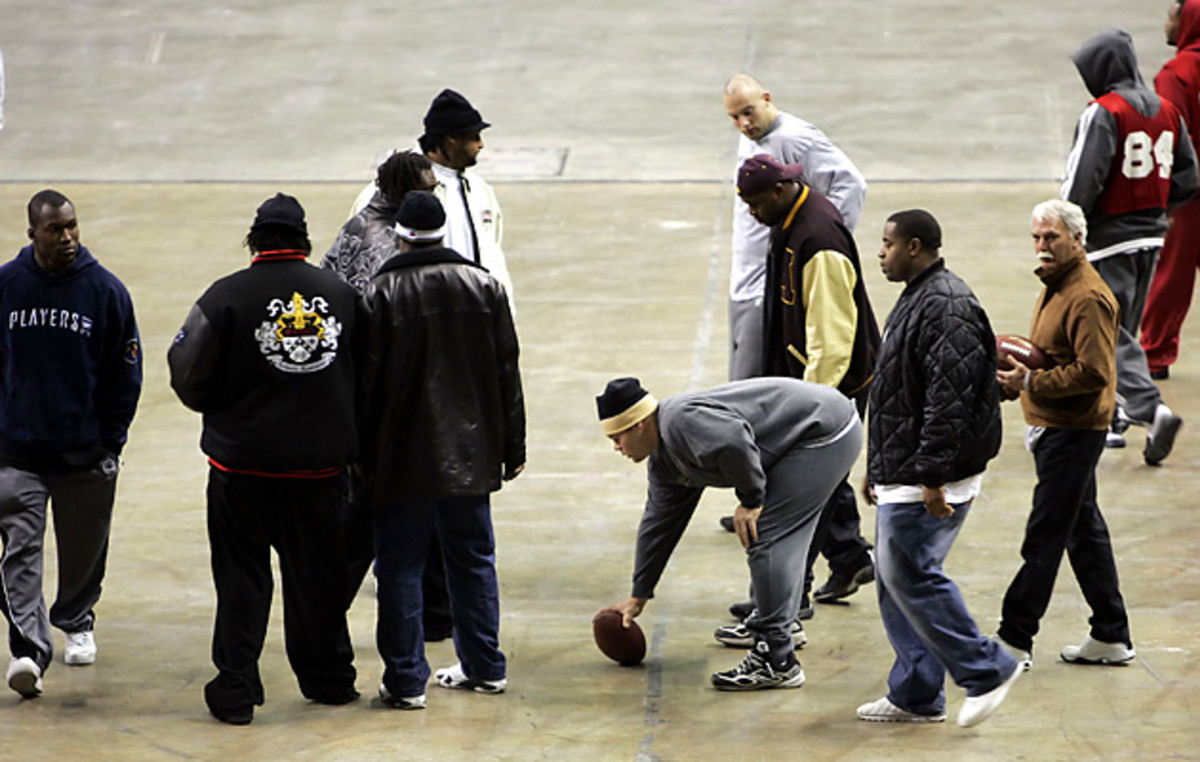

With the Superdome non-operational for 2005, the Saints play all of their home games on the road at various stadiums.

The Saints play their first regular season home game at Giants Stadium. Against the Giants. As storm damage is assessed, uncertainty about the team's future looms.

"Honestly, I thought we were never going back to New Orleans. Even if they built up the Superdome, who would be there to watch our games?"

McAllister:To think that we had a home game in New York, you had to laugh about it, it was literally a joke. Literally. I know the league was trying to accommodate us but to say that we had home-field advantage was not the case whatsoever.

Bensel: Mom and pop companies folded tents and never came back. Big companies left for other cities. However, we were the focus. Every finger pointed to the Saints. ‘Are you guys coming back?’ Dealing with those questions was more disconcerting to us than anything. The New Orleans Saints are part of the social fabric of the city.

Smith: Honestly, I thought we were never going back to New Orleans. Even if they built up the Superdome, who would be there to watch our games?

• KING: How the Saints helped NOLA rebuild after Hurricane Katrina

October 3, 2005: Thornton visits the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) office in Baton Rouge to seek financial assistance for rebuilding the Superdome.

Thornton: FEMA would pay to repair if it were not more than 50% damaged, meaning 50% of the replacement value. If the cost of repair is more than 50% of the damage, they will tear down the building and build a new one. It became clear to me that it would have to be a renovation. Furthermore, FEMA would not pay for areas of the stadium that were damaged but might not match other areas of the stadium that are repaired.

October 11, 2005: Thornton and SMG have a meeting with Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco.

Thornton: We didn’t have a day or minute to waste. I say to her that our preliminary indication by our architects is that they think it can be saved. We believe it’s our only chance to renovate the dome. There’s no way we can tear it down and build a new stadium. She’s agreed, even though her own staff questioned her. Had she hesitated for even a week, we could have lost valuable time. She understood that getting the dome back would not only be symbolic but would create jobs to bring people back and rebuild the neighborhoods.

[pagebreak]

October 30, 2005: On the morning of the Saints’ first of four “home” games to be played at LSU Stadium, a move by the NFL to promote connectivity to the recovering region, NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue, NFL executive vice-president, chief operating officer Roger Goodell and NFL executive vice-president Joe Browne, in town for the occasion, request a meeting with Thornton.

Thornton: They wanted to know what it would take to rebuild the Superdome. I explained the $200 million, and the over two years and so forth. I explained to them that one of our biggest challenges was with FEMA and the difference between repair and renovation. Tagliabue said to me, ‘You can’t be the same old Saints in the same old dome. Now’s your chance to make it a better place to erase all those images of Katrina.”

The NFL would later kick in $15 million to help with improvements. SMG refinances the Superdome’s debt and borrows $65 million in new money.

December 5, 2005: Tagliabue, Goodell and Browne undergo an extensive tour of the damaged areas of New Orleans, including the Superdome, which was still a shell of itself.

"He said, 'I don’t care about those things. Just give me a turf and make it safe for the fans. We’ll play football.'"

Thornton: On December 7, Roger called and asked if there was any way to accelerate the schedule and get it open by September. The league needed to plot out where the Saints would play in 2006 and preferred the Superdome. I said I didn’t know, and Roger asked if it would help if the league kicked in some money. I said that money always helps but it’s a matter of a lack of manpower and materials. You just couldn’t get labor around there. I asked him to give me a few days.

I called him back on December 15 and said I think he can do it. But here are the conditions: We won’t have all the suites ready. There won’t be granite counter tops or fixed seats in the suites. We might not have all the concession stands and restrooms. He said, ‘I don’t care about those things. Just give me a turf and make it safe for the fans. We’ll play football.’

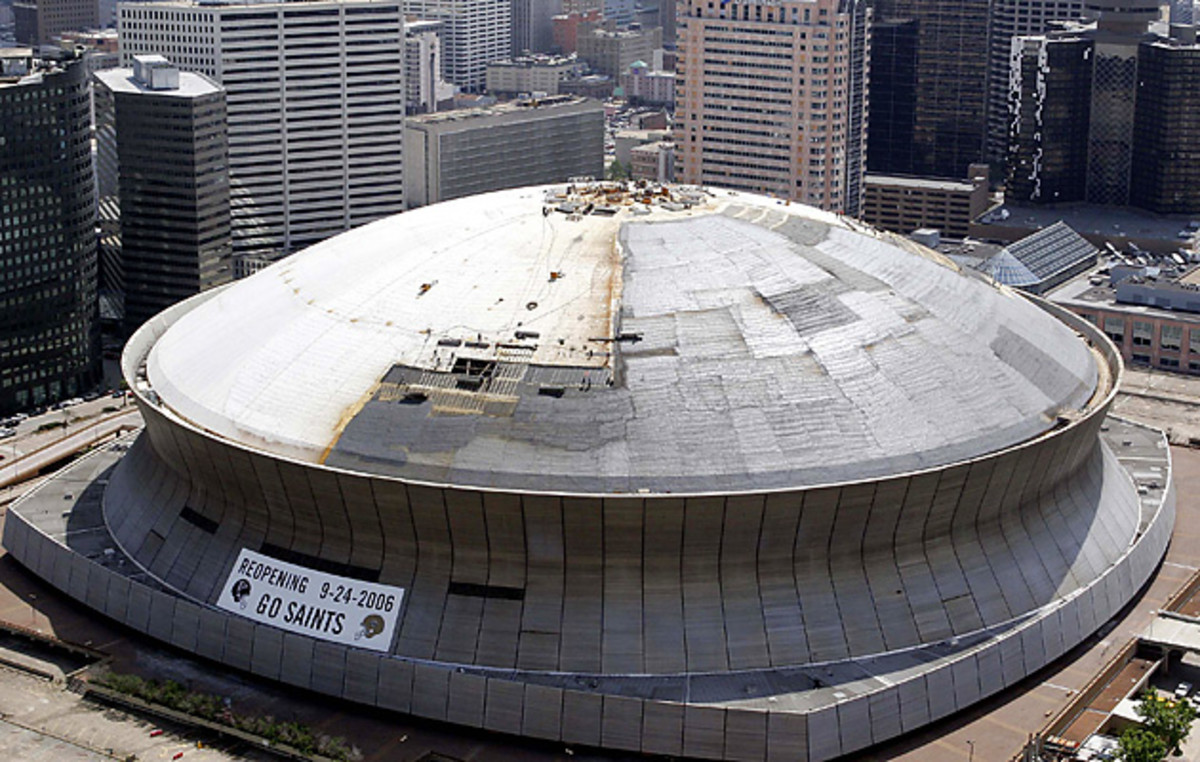

December 30, 2005: The Saints announce they are coming back to the Superdome in 2006.

Thornton: The project really accelerated when we had the momentum of the NFL and the Saints behind us. We just had to get it done.

The Saints finish the 2005 season at 3–13 and fire head coach Jim Haslett. The search for a new coach, as well as valuable free agents proves inherently a challenge.

Loomis: I think there were 10 teams looking for new coaches that year. When you line up the openings, given the circumstances, we were 10th in line in terms of a desirable job. When you come back here and see the devastation, the blue tarps on roofs, That’s a hard sell. It’s a hard sell for players with families.

January 18, 2006: The Saints announce the hiring of new head coach Sean Payton, who was an assistant under Bill Parcells in Dallas but was still a relative unknown with no head coaching experience.

March 13, 2006: Unrestricted free agent linebacker Scott Fujita becomes the first veteran to sign with the Saints.

"There was nothing conducive to having a team that might be remotely successful. We didn’t have a building to play in. But that was part of the draw."

Fujita: For my wife and I it felt like an opportunity to be a part of something that was bigger than just football. Everyone thought we were pretty crazy.

I remember taking the drive from the airport and the only restaurant that seemed open was Popeye’s Chicken. All the street signs were still gone. You could see the water lining the free way overpass. There was nothing conducive to having a team that might be remotely successful. We didn’t have a building to play in. But that was part of the draw. I just didn’t think I’d have an opportunity to be part of a rebuilding effort literally and figuratively. We thought we’d give it a shot and see what happens.

March 14, 2006: Free agent quarterback Drew Brees signs with the Saints right after the Miami Dolphins pass on him due to concerns about a recent shoulder injury.

• KLEMKO: Looking back on Saints' class of 2006, ten years later

September 25, 2006: With 70,000 fans and supporters gathered from around the globe, the Saints make an emotional return to the Superdome to play the Falcons. It is 638 days after their last real home game. Bono takes the stage and dignitaries ranging from President George H.W. Bush to newly appointed NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell are on hand.

Steve Gleason’s blocked punt that teammate Curtis Deloatch landed on in the end zone on just the fourth play of the game set the tone for the game and the season. The Saints beat their divisional rival that night 23–3.

"If I had to, I was ready to die that game."

Goodell: The city and Superdome had a Super Bowl-like atmosphere, and you could sense that it was more than another football game.

McAllister: I think every player at some point shed a tear, especially if he was on the team the year before. Because of the electricity in that stadium, I think the hair on every player’s skin stood up.

Horn: Everything was slow motion. I could hardly breathe because I was too excited so I had to go to the oxygen machine every time I came to the sidelines to calm me down. That’s how much I wanted to be part of us winning that football game. If I had to, I was ready to die that game.

Goodell: The noise after Steve Gleason’s punt block in the first quarter was deafening but resonated around the world as a symbol of the resilience and rebirth of New Orleans. We knew that many challenges remained for the people of that region. But for one night, the NFL and the Saints gave people of the Gulf Coast a reason to celebrate and be proud. The game will rank among the NFL’s finest moments. It came together because of the determination and hard work of Tom Benson, the Saints organization, the leadership in New Orleans and Louisiana, the people of New Orleans, and the NFL’s commitment to support the region.

Loomis: For me, personally, that game was even more meaningful than the Super Bowl.

The Saints went on to win four of their first five games in 2006. They end the season at 10-6 and advance to the NFC Championship. They would win Super Bowl XLIV just three years later.

"It was then that I realized that it was the people of New Orleans who gave the Superdome its life."

Thornton:Ironically I was on the field when U2 and Green Day took the stage. I realized I was standing in almost the exact location I stood when the roof was being blown away. I wanted to see the faces in Section 137, which was exactly where people were huddled when debris was falling. I realized for the first time in a year I was seeing happy faces this time. It was like a tingling in my spine. It was then that I realized that it was the people of New Orleans who gave the Superdome its life.