Constant relocation takes its toll on NFL wives

The midsummer sun shines on the red 49ers jerseys as the players practice at preseason camp in Santa Clara, Calif. Next to the field, near the weight room, the players’ and coaches’ wives and children sit on white folding chairs and watch in the shadows.

Almost a third of the players are new to the Niners. In a league where the average lifespan is 3.5 years, the threat of a career-ending injury is constant and few contracts are guaranteed, they’re under searing pressure to focus and perform. 10 of the team’s 14 coaches are also new. As the season goes on, their days will stretch deeper and deeper into the night.

In other cities across the NFL, the demanding rituals of relocation are well-known to the families of players and coaches: contact the realtors, study the school systems, pick a community, find the new doctors, handle the kids’ emotions, shed an old life and start afresh. The teams help, but inevitably much of the burden falls to the wives and girlfriends and significant others. They’re the ones whose work every day allows Sundays to remain paramount for the pros.

For the past two years, George Warhop has coached the offensive line of the Buccaneers. He and his family—his wife, Lori; son, Jacob; and daughter, Olivia—are settled and happy. Jacob, 17, is an aspiring artist who works mostly with pencil and charcoal. Olivia, 19, will be a freshman at Elon (N.C.) University in the fall and plans to double-major in business and marketing. But six years ago things were different for this family. They weren’t just difficult; they were touch and go.

In May 2009, seven months after George was fired as the 49ers’ offensive line coach and three months after he took the same job with the Browns, Olivia started feeling pain in her left leg. George couldn’t help—he’d already relocated from Northern California to Ohio—so Lori contacted the 49ers’ trainer, Jeff Ferguson. He got Olivia immediately into Stanford Hospital, where a large tumor was discovered in her tibia.

The pathology report indicated a benign growth, so the Warhops were stunned when, 10 days later, Olivia’s doctor rushed into the examining room as her stitches were being checked and announced that he had diagnosed a potentially fatal bone cancer. “You can’t move to Cleveland,” he told Lori. “Olivia has to stay here and have tests. You’ll be lucky if we don’t have to amputate.”

2015 NFL team-by-team previews

But Lori knew what was best for her family: She moved the kids to Ohio. Trainers and team doctors from the Browns connected Olivia with the Cleveland Clinic where Olivia received an eventual diagnosis of MyroFibrosarcoma, an extremely rare form of bone cancer. But her leg didn’t need to be amputated, and after a six-hour tibia resection, followed by a six-day hospital stay, followed by wheelchairs, crutches, rehab, three bone grafts, two plates along her tibia and 13 screws, she was declared cancer-free one year after the initial diagnosis.

The summer Olivia was in the hospital, Lori spent every day with her. George, while coaching two-a-days, went to his daughter’s room at night and slept in a chair by her bed.

The Warhops’ harrowing story is not typical of NFL families, but parts of it are all too familiar. “Everybody thinks the football life is so glamorous,” says Lori. “But there are people in the trenches who do a lot of the hard work. For the team, it’s the coaches, the equipment guys, the trainers. For the [players], it’s the girlfriends, the wives.”

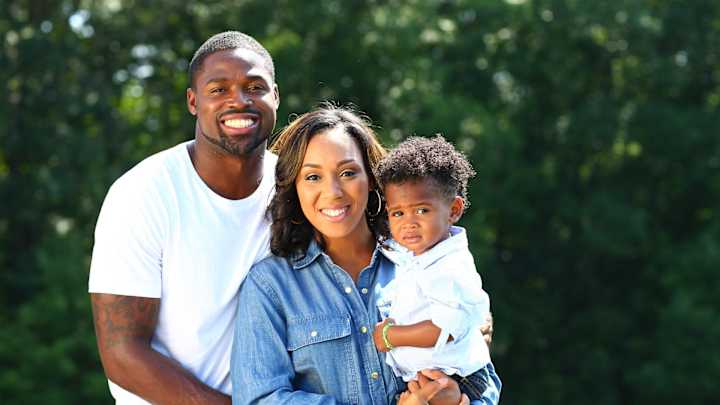

Chanel Smith thought she was moving to San Francisco. Her husband, Torrey, who led the Ravens in almost every receiving category each of the past two seasons, signed a five-year, $40 million free-agent contract with the San Francisco 49ers in March. What Chanel didn’t know was that Torrey’s new team was based roughly 45 miles south of San Francisco, in Santa Clara. “I knew nothing about this area,” Chanel says.

For two weeks after his signing, Torrey, 26, searched for a place in San Jose, just southeast of Santa Clara, while Chanel hung back in Baltimore with their one-year-old son, T.J. “I was kind of boycotting,” she says. “ ‘I’m just going to stay here, and we’ll come visit you.’ Typical overreacting response.” The Smiths’ house outside Baltimore was 4,800 square feet, with five bedrooms, a large playroom for T.J. and a 2 1/2-acre backyard. But for the monthly payments on its mortgage the Smiths could get only a small apartment in San Jose.

“Torrey was O.K. with a little apartment,” says Chanel. “That’s great—but we have a baby. T.J. needs space to run around. And, coming from a house, I feel claustrophobic in an apartment. So we waited an extra week and got a three-bedroom townhouse."

Torrey suggested furnishing the 1,300-square-foot house himself before Chanel moved out from Baltimore. “She was like, ‘No,’ ” he recalls with a laugh. “ ‘You’re not picking out anything.’ ”

“He’s an impulse buyer,” Chanel explains. “If I left it to him, nothing would match and I would be very upset.” So Chanel joined her husband in San Jose in April and furnished their new abode herself. She put together T.J.’s bookcases, an entertainment center and the furniture in the kitchen. She handled the cooking, cleaning, shopping and everything having to do with the baby. “Coming to a new team is a big change for Torrey,” says Chanel. “He goes to practice and he’s there until three. When he gets home, he does a lot of studying. So I try to handle as much as I can. He chips in when I need him to, but during the transition I want him completely focused on adjusting.”

Chanel has her own job as vice president of the Torrey Smith Foundation, a children’s charity in Baltimore, and she’s studying for her MBA at Miami—but her main occupation is managing Torrey and their family. Sometimes the manager loses her patience. “We fight about changing diapers,” Chanel says. “We have a deal where if you smell it, you change it. Torrey will act like he didn’t smell it, or he’ll make T.J. walk to me so I smell it and change the diaper.”

For Chanel, caring for the baby has been the hardest part of the transition. “In Baltimore I had help,” she says. “My best friend lives in Maryland. My mom lives two hours north. Torrey’s family lives two hours south. I enjoyed having people over for the weekend, taking T.J. from me. Out here, I’m by myself. A five-hour flight with a baby is no fun; I won’t be making too many trips home. It’s going to be really rough.”

[pagebreak]

Sometimes the coach or player doesn’t have a wife. Or he does, but she lacks the prodigious energy or the organizational wizardry of Lori Warhop or Chanel Smith. He needs a savior.

The Browns’ coaches call her Batman. They send out a signal—text, email, phone call—and she appears. Others call her Godmother. Her real name is Linda Musarra, and she’s a real-estate agent in Cleveland, where she specializes in helping professional athletes and coaches. For the single guys, she is also a de facto wife.

From arranging homes and rental apartments to shopping for groceries and furniture, Musarra is her clients’ “go-to girl,” as she puts it. She can also be a companion, a mother or a therapist. “I try to become a confidant, a part of the family,” she says. “I’m the gal who, when you’re alone and things are going bad and you played lousy and you got hurt and you can’t cry in front of the coach, you pick up the phone and call me. It’s completely private.” After her clients get traded or fired or move elsewhere for another job, they still call her.

When Musarra first meets a player or coach, she introduces him to her car. The car’s name is Vegas, and Vegas has rules. Vegas is a massive black Mercedes S550 (Musarra gets a new one every year) with leg room for a 7-footer in the passenger seat. Whatever is talked about in Vegas stays in Vegas. Also, there’s no swearing.

“What if I want to cuss?” an athlete once asked Musarra. “I like to cuss. That’s how I talk.”

“I appreciate that,” Musarra said, “but you can’t do that in Vegas. If you want to be with me, you’ll respect me. I’m a lady, and I presume you’re a gentleman. Are you going to prove me wrong?”

“What if I say no?” the athlete asked.

“You’re going to miss the best deal you ever had.”

The client didn’t cuss.

Besides Browns players, Musarra handles relocated Cavaliers and Indians. She found a house for first baseman Carlos Santana and his wife, Brittany. That four-story mansion sold for $1.2 million in 2009. About a year later Musarra got it for the Santanas for $361,000.

During the off-season, Musarra checks on the house while Carlos and Brittany winter in the Dominican Republic. If anyone breaks in, the security company calls Musarra, not the Santanas. “She always comes through for us,” says Brittany. “She takes me to the airport at four in the morning and never accepts anything in return. If it weren’t for her, I don’t know what we would do in Cleveland.”

In May, Brittany gave birth to a baby girl named Savian Yazmin. Brittany had asked Musarra if she would be around for the delivery. “Absolutely,” Musarra said. “You have clients,” Brittany said. “Come when you can. Pop in and out.”

Brittany was in labor for 24 hours, and Musarra never left her side. At one point, worried that she had overstepped her boundaries, Musarra asked, “Should I leave? I know it’s just family.”

“Are you crazy?” said Carlos.

“You’re family,” said Brittany.

Planning your Fall: Ranking each and every week of the 2015 NFL season

Marc Trestman felt a nudge. “Hey, check her out,” said his dad, Jerry. The two men were at a Cleveland clothing store called Hemisphere. It was 1989, 10 jobs ago for Marc, when he was the Browns’ offensive coordinator. He was talking to one of the young women behind the counter, but she was not the one Jerry had his eye on. He was checking out Cindy.

Several months later Marc went back to Hemisphere and asked for Cindy’s number. “It was a fairytale for me,” says Cindy, now 57. “I grew up in Cleveland. I was a big Browns fan, and I had this vision: white picket fence, living near my family.”

Two years later Marc and Cindy got married. They were in Honolulu for the Pro Bowl, and, as Marc wrote in his 2010 book, Perseverance, “the tropical air took effect and I proposed.” They were wed one day later on the 16th hole of the Westin Kauai Lagoon golf course. The only guests were Mike Holmgren (then the 49ers’ offensive coordinator) and his wife, Kathy. The two couples were staying at the same hotel and had run into each other the morning before the wedding.

Marc called up Browns coach Bud Carson and asked if he could spend another week in Hawaii for a honeymoon. “Go enjoy yourself,” Carson said. But the night after the wedding, as Marc and Cindy walked into their hotel room, they noticed a red light flashing on their telephone. The message was from Carson: “You’re fired.”

Cindy remembers breaking out in hives. “I never thought I was going to stay in Cleveland the rest of my life,” she says, “but at least a year. Or a day. How’s a day?”

Since then the Trestmans have moved 14 or 15 times—they’ve lost count. “Marc is never around for the move, of course,” says Cindy. “Which I prefer. He’d just get in the way. He’s not used to being home. He doesn’t know where anything goes. And he doesn’t write checks. Maybe one month out of the year he tries to, but I’d rather him not. I’m the CEO of the Trestman family.”

The CEO doesn’t move anymore. She decided to stay in Chicago when Marc, 59, moved to Baltimore last January to become offensive coordinator of the Ravens after he was fired as head coach of the Bears. “The older you get, the harder it is to make connections in a new city,” Cindy says. “When your kids were in school, you made friends through their friends’ parents. Now that our girls are in college, I’m on my own.”

• KAPLAN: How many NFL blunders will the owners tolerate?

For Marc, the transition to a new city is easy. He works, exercises and eats at the team’s facility. When necessary he sleeps there. And when he walks into a new facility, he already knows people—someone he coached against, someone he worked with on another team, someone he met at the combine or the Senior Bowl. He has a built-in fraternity, an innate support group.

Cindy doesn’t. “You become close with one or two of the wives,” she says, “but it’s really hard to hang out with them because there is so much politicking involved. For instance, does that wife’s husband get along with my husband? The ones who didn’t like my husband, I felt like I knew that because of the way their wives would treat me.”

On Sundays the wives of the defensive coaches tend to sit in the same section of the stands. They do their best not to offend one another if things go badly. No groaning or yelling or assigning blame. That doesn’t work for Cindy. “I’m Italian,” she says. “I like to scream a lot. So I prefer to sit by myself.”

[pagebreak]

Ashlee Pears doesn’t mind sitting beside other players’ wives at home games. One time in Denver a fan who was sitting next to one of the wives left his seat to visit the concession stand. As soon as he got up the wife put her purse on his seat, as if claiming it for her own. When the fan came back with his hot dog and saw the purse, he dropped it on the ground and sat down. The wife shrieked, “My purse does not belong on the floor!”

“Just the tone—I couldn’t believe it,” says Ashlee. “I was so embarrassed, I had to apologize to people in our section: ‘We’re not all like this, I promise you!’ ”

Most of the time, though, she nervously locks her eyes on the field and stares at her husband, guard Erik Pears, 33. “I usually have a beer or two right from the start,” Ashlee says. “Watching someone you love possibly get hurt, ruin their career, ruin their life through an injury . . . what would you do? What would he put on his résumé? No one cares that he was a football player.”

Ashlee used to observe just the offensive line; only recently has she started watching the defensive side. “I’m hoping we win, but I’m watching to see if my husband gets up after every snap,” she says. “I feel bad for my kids when we watch away games at our home. I tell them, ‘I can’t talk—I need to focus.’ I end up rewinding if it looks like my husband got up slowly.”

When Ashlee and Erik got married, in 2008, Erik’s fourth year in the NFL, she was pregnant with their first child, Lukas. Now he is six, and the Pearses have three other children, the youngest having arrived in May. “I would not trade where I’m at now for where I started,” says Ashlee. “I was a new mother, and Erik was gone. I was dealing with post-partum depression, moving, school, the kids. The kids are a crisis. They don’t understand the lifestyle. They get it only to an extent.”

Would Ashlee recommend being an NFL wife to other women? “God, no,” she says. “Maybe if it was a different sport, but not football.” Ashlee says she’s ready for a stable life. “Let’s just have our consistency, our nine-to-five.”

Forget that. A free agent this off-season, Erik signed a two-year contract in March with San Francisco, his seventh pro team if you include a one-year stint with NFL Europe’s Cologne (Germany) Centurions. So it was time for the Pearses to pack up and move again, this time from Buffalo.

“I have to do everything,” says Ashlee, who had moved with Erik twice already. “Usually Erik is in camp, so it’s me and a moving company. Teams don’t offer a whole lot. The 49ers have been the most helpful. The biggest thing they’ve done is help us find a place to live. Their [real-estate agent] was fantastic.”

Following an off-season workout, Erik sits at his locker and tries to wrap his head around what his wife does for him. “Schools, doctors, appointments, getting everything lined up for the season—she takes care of that,” he says. “I can’t tell you how tough it is.” He pauses, then self-edits. “I don’t know exactly how tough it is, because she’s the one doing it.”

No one knows exactly how tough it is better than Lori Warhop. Now 52, she still lives in Cleveland even though George, 53, moved to Tampa in 2014. Yes, they are still married. And yes, Olivia is still well.

Lori and George simply didn’t want to move their two children while they were in high school—an arrangement that’s growing in popularity among NFL families facing similar situations. Jacob Warhop is a high school junior, and once he’s in college the plan is for Lori to join George wherever he’s coaching. “If she still likes me,” George jokes.

Meanwhile she’s finishing a project she started in 2008, before their daughter’s ordeal. Lori is working with a web developer to build a website, Livingprosports.com, to help players’ and coaches’ families move from city to city. “When you move, if the new team gives you any information, they give it to you upon arrival,” says Lori, but that is “already too late. And that information typically covers attractions, museums, restaurants—not the nuts and bolts of life.”

One team’s resource pamphlet for families in transition details the club’s ticket policy and stadium information. It outlines the team’s travel arrangements and recommends area attractions, churches, fitness and health clubs, golf courses, grocery stores and hotels. There’s a little section on restaurants, hair salons, specialty shops, transportation, medical resources, household maintenance and preschool programs. That’s about it.

Lori aims to do far more with her site. She’ll direct wives to the best schools, tutors, dentists, orthodontists, pediatricians and more in all 32 NFL cities—information she gathered from other coaches’ wives and from people she met during her odyssey through the game, including stops in college football and in NFL Europe. “I’m trying to make it as seamless as possible for families to move,” she says.

George Warhop has his own vision for his wife’s website. “Her scope might be a little narrow for what this could be,” he says. “Anybody who has to move, they all have the same issues. To have somebody who has been involved and who knows makes a big difference. This would be helpful for wives in general.”