From Apprentice to Master

FLORHAM PARK, N.J. — The text messages come sporadically. Bill Parcells, ever a coach, knows how to pick his spots.

He sent one at 4:19 a.m. on Sept. 22, the morning after the Jets had delivered a perception-changing win in Indianapolis on Monday Night Football.

“Congrats,” Parcells wrote to Todd Bowles. “This is a good week to be demanding.”

Exactly two minutes later, the rookie coach replied, Thanks, I will. Parcells was pleased. He wanted to make sure Bowles wasn’t, in his words, “eating any cheese” after the win. Sure enough, Parcells’ latest protégé was already in his office, starting over in the wee hours for the next game.

“He gets it,” Parcells said. “We don’t have to have a lot of dialogue.”

Six weeks into the season, Bowles’ Jets are 4-1 and one of the early surprises. Led by a journeyman quarterback, Ryan Fitzpatrick, who became the starter after a locker-room punch, and by a No. 1 receiver, Brandon Marshall, who had been cast off by three other teams, New York’s offense is averaging nearly 26 points per game, placing it among the top 10 in the league. The defense, schemed by Bowles, is even better, yielding the fewest total yards and points per game in the NFL, and ranking third with 15 takeaways.

This Sunday, the Jets will travel to Foxborough and take on the undefeated Patriots for first place in the AFC East, a scenario that virtually no one anticipated going into the season. “Uh-oh. What would y’all say then?” veteran guard Willie Colon asked reporters in front of his locker after Sunday’s 34-20 victory over Washington. Most in the Jets’ locker room are saying exactly what Bowles is saying, that one game won’t make or break them, even if it will go a long way toward showing everyone just how good they really are.

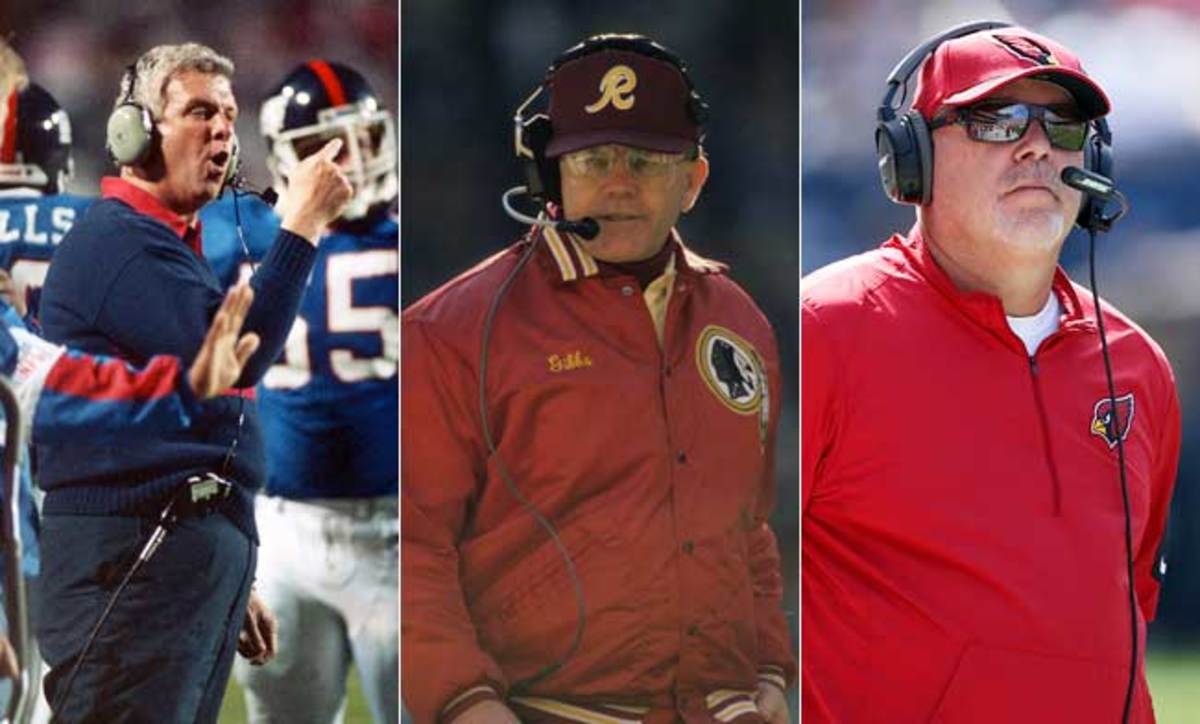

The Jets have taken on Bowles’ personality: even-keeled, quietly confident and undeterred by adversity. And Bowles is reflecting the best attributes of the NFL coaching greats who spent years grooming him for this chance, whether he realized it at the time or not. Since his sophomore year in college, Bowles has been learning from the likes of Bruce Arians, Joe Gibbs and Bill Parcells. Now, Bowles says with a hearty laugh, “I’m trying not to embarrass them.”

• THE BRONCOS ARE BLEMISHED: Peter King’s Mailbag

* * *

Arians might have been the first to see it, 32 years before the Jets named Bowles their 16th head coach. In 1983 Arians became the head coach at Temple, where Bowles was a mustachioed sophomore safety for the Owls. Bowles became Arians’ captain and ran his secondary, and as Arians puts it, there was never any question that things were going to get done the right way with Bowles in charge of DBs. As a senior, he dislocated six bones in his left wrist during a practice in late August but only missed three games.

“I think I hurt him once,” Arians said last week after an Arizona Cardinals practice. “I said to him, ‘I’m not sure being a pro football player is in your future. But coaching, I can tell you you’re going to be a great coach.’ Of course, he wanted to play, so I think it hurt his feelings when I said that.”

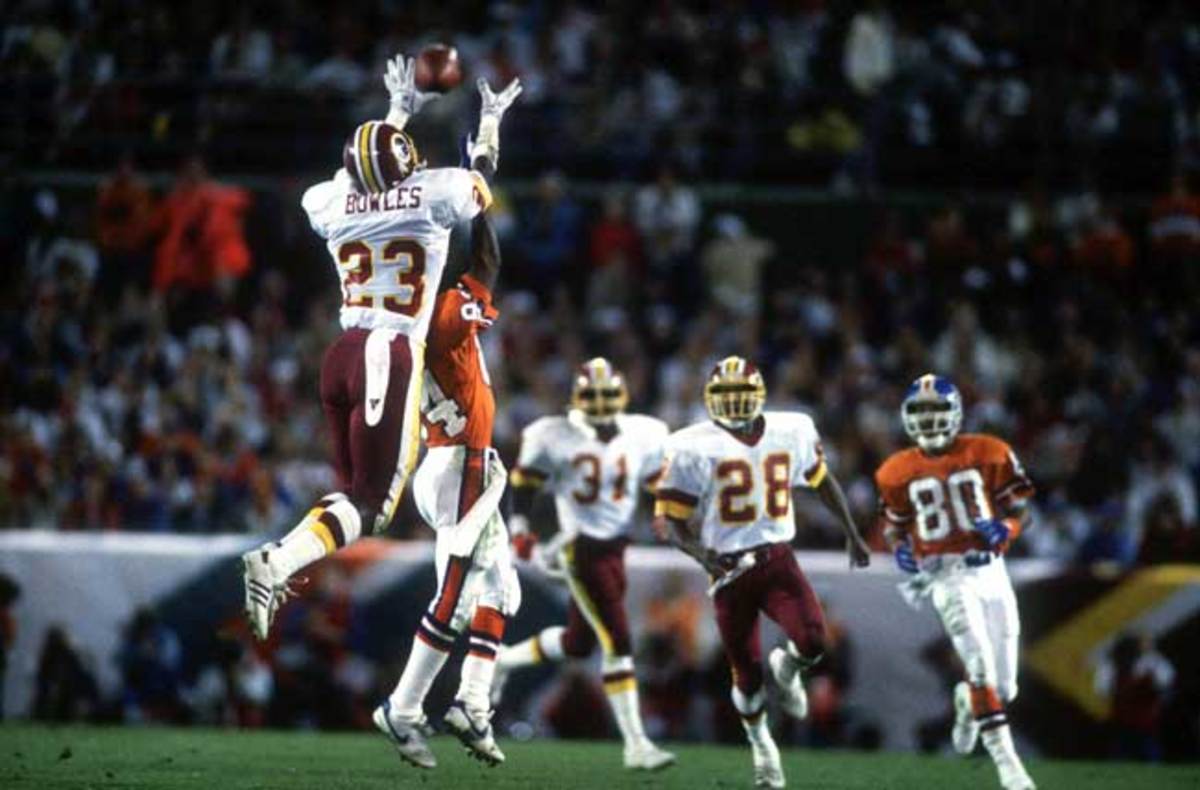

Arians was wrong on one count, but he was a visionary on the other. Bowles played eight years in the NFL, an undrafted free agent who maximized the length of his career by using his smarts. During his seven seasons in Washington, Bowles learned how defensive coordinator Richie Petitbon’s creative schemes put players in positions to succeed, and then it was Bowles’ responsibility to make sure they were in those positions out on the field.

“I am very thankful,” says Joe Gibbs, his head coach in Washington, “because he helped keep me in a job for about 12 years.”

Gibbs’ team was in a perennial NFC East dogfight with Bill Parcells’ Giants, a legendary era during which Gibbs won three Super Bowls and Parcells won two. Bowles was part of the 1987 Super Bowl XXII-winning team, and one thing about Gibbs that stuck with him was the coach’s relentless quest to get better and to never be satisfied. “He understood that better than anybody,” Bowles says.

Anyone who has worked with Gibbs knows one of his favorite sayings: “In football, you are never more than two hours away from a disaster.” Bowles found that out quickly during his Jets tenure. On the opening day of training camp, news broke that defensive lineman Sheldon Richardson, who was already facing a four-game drug suspension, had been arrested for allegedly street racing and resisting arrest during the summer break; less than two weeks later, linebacker IK Enemkpali punched presumptive starting quarterback Geno Smith over an unpaid debt during a locker-room encounter, breaking Smith’s jaw.

Bowles handled both situations the same way in private and in public: He addressed it, and made it clear the team was moving on. Stop talking about it, he told his players. Leave it alone. He announced that the starting quarterback job was Fitzpatrick’s as long as he was playing well, and then Bowles and offensive coordinator Chan Gailey made sure they put the veteran in a position to do just that, leaning on a strong running game and creatively deploying Marshall and Eric Decker to give Fitzpatrick places to throw.

In the first half of last Sunday’s game, three ugly turnovers led to Washington scores and a 13-10 deficit at halftime. In the locker room, Bowles relayed a message that he had told his players countless times before: We’re going to face adversity, but you have to have the mindset that we’re going to win anyway.

“His intelligence and evenness of personality—which are two things Joe Gibbs had—that’s what helps you in crisis situations,” says Charley Casserly, the GM in Washington when Gibbs coached and Bowles played there and a consultant to Jets owner Woody Johnson during last winter’s hiring search.

* * *

Bowles’ very first coaching offer came via another legend, Doug Williams, the first African-American starting quarterback to win a Super Bowl. He had considered Bowles to be something of a little brother since 1986, when they were teammates in Washington. Williams was hired to coach the Morehouse College football team in 1997, and he wanted Bowles to line up his defense, just as Bowles had done for Joe Gibbs.

“Ahh, I don’t know,” said Bowles, who was working as a scout for the Packers.

Williams asked him to think about it. He called Bowles back. And then he called again. Finally, Bowles said he’d give it a shot. “I never heard Todd say, ‘I want to coach,’ ” Williams says. “I never heard him say he didn’t want to coach, either. All I needed was for him to give it a try.”

As Williams puts it, no one goes to Morehouse just to play football. Being able to field a defense that could even keep the team competitive was the beginning of Bowles’ noted creativity as a coach. Sending three straight blitzes off the edge, as he did in a Week 4 win against the Dolphins this season? Most defensive play-callers would be reluctant, but Bowles learned very early on to say, Why the heck not?

Bowles worked with Williams for three seasons, one at Morehouse and two at Grambling State, before Al Groh, then the Jets’ coach, asked for permission to interview Bowles to be his secondary coach. “You don’t need permission,” Williams told Groh. “All you have to do is hire him.”

Bowles’ next NFL gig came with the help of Arians. Butch Davis was putting together his Browns staff in 2001. Arians was the offensive coordinator. They had Chuck Pagano to coach the secondary, but Davis was looking for another coach on the back end, someone to scheme up the nickel packages.

“I told him, ‘You gotta look at Todd Bowles. Just talk to him. You’ll love him,’ ” Arians says. “He did. He hired Todd. Look back at that first year Todd was there. Remember a kid named Anthony Henry? Cornerback? Free-agent kid, rookie, and he intercepts 10 balls that year. Everybody’s saying, ‘How’d that happen?’ Who was his coach? Todd can really coach young kids up.”

That season the Browns’ defense set a franchise record with 33 interceptions, 28 by defensive backs. In 2003 the Browns tied another club record, allowing only 13 passing touchdowns. But it wasn’t even those results that landed Bowles a job with his next coaching mentor.

* * *

Bill Parcells didn’t personally know Bowles as a player, but he felt as if he did, having faced the shrewd safety twice a year during those great Washington-New York rivalry years. It’s a classic Parcells tactic that Bowles has adopted: knowing your opponents as well as your own players, understanding what makes the guys on both sidelines tick. Bowles’ ability to do that in his Jets interview—how he offered psychological profiles of opposing players when asked how to defend them—stood out to the decision-makers in the room.

Parcells was the Jets’ general manager the year that Bowles coached their defensive backs, and in 2005, when Parcells coached the Cowboys, he hired Bowles for his staff. Bowles worked for Parcells for two seasons in Dallas. They never talked specifically about what it takes to become a head coach, but Bowles remembers hundreds of conversations that, “in hindsight,” he says, “I guess he was grooming me.”

Parcells would often pull Bowles aside after practice and ask him, “What did you see today?” Not among his position group, but from the team. How did you think the offensive line performed? Did the quarterback hold the ball too long in 7-on-7s? Parcells, whose coaching tree includes six of the 32 current NFL head coaches, wasn’t so much seeking answers as he was trying to alter Bowles’ perspective. If one of Bowles’ players messed up in practice, Parcells would ask him how many times he’d instructed that player on what to do. No matter what Bowles said, Parcells replied that he should have told him one more time.

There’s a Parcells truism that Bowles has internalized: Don’t tell me about the pain, just deliver the baby. In other words, if you’ve got problems, I don’t want to hear about them, just get it fixed. Wherever he coached, Parcells was always the boss, so it’s as close to mushy as Parcells gets when he says of Bowles, “He’s the boss, too.”

Bowles’ last stepping stone to becoming an NFL head coach came from his old college coach. After stops in Miami, where he served three games as an interim head coach after Tony Sparano was fired, and Philadelphia, where he succeeded Juan Castillo as interim defensive coordinator, Bowles was hired by Arians to coordinate Arizona’s defense in 2013. Both men share a great capacity to teach, and also to get fiery when needed, despite Bowles’ mild-mannered reputation. “A couple of times, at halftime, he wasn’t happy with our defensive performance. And boom—he flips a table over,” Arians recalls. “People rush in to look. What happened? It’s just Todd.” That side has come out at times in New York, too. After the poor first-half performance against Washington, players said Bowles roared at halftime, “What type of team are we going to be?”

Arians is a coach who never lets fear get in the way of taking big chances. His preference on offense is to throw the deep ball rather than taking the check-down. And Bowles mirrored that on defense. During his two seasons with the Cardinals, they blitzed on 46.5% of drop-backs, the highest rate in the NFL according to ESPN Stats. It was partly because of necessity—the Cardinals suffered from a dearth of outside pass rushers—but it was also because Bowles isn’t afraid to take chances.

Many of Bowles’ players have never met Arians, or Gibbs or Parcells, but they understand the influences that these all-time greats have had on their coach. Fourth-year linebacker Demario Davis has heard stories about how Parcells’ mind was always on football, even calling assistants or players in the middle of the night. Davis hasn’t received any such call from Bowles, but it’s a regular occurrence for Bowles to stop him in the hallway and remind him of a tendency about that week’s opponent.

It happened before the Eagles game in Week 3. Each time Bowles passed Davis at the Jets’ practice facility, he reminded him that when Philadelphia runs a mesh concept—with a receiver, tight end and running back on the right side of the formation—he should expect to see the back running a wheel route out of the backfield. That’s exactly what happened in the game, but Davis got mixed up. He thought the Eagles were employing a different concept that would send running back Ryan Mathews out on a flat route. Davis came up to defend the flat, and Mathews rolled past him on the wheel route, scoring a 23-yard touchdown to give the Eagles a 17-0 lead. The 24-17 loss to Philadelphia is the lone blemish on the Jets’ record so far.

“If I had been paying a little closer attention to Todd,” Davis admits, “I would have been on top of that play.”

* * *

In January, when Bowles met with the Jets’ brass for the first time, he carried a notebook that he never had to open. His command of the interview, and his presence in the room, blew away a contingent that included owner Woody Johnson, team president Neil Glat and consultants Casserly and Ron Wolf, the former Packers GM.

“After Todd’s first interview, I would have signed him right there,” Casserly says. “He was my first choice.”

But Johnson would make the final decision, and he wanted to exhaust the search process. The Jets were also courting the other top head-coaching candidate, Dan Quinn, who was unavailable to be hired until Seattle’s playoff run ended. During Bowles’ second interview, while Quinn’s Seahawks were preparing for the NFC Championship Game, the Jets offered Bowles the job.

Casserly had been in regular contact with Bowles over the past year, through his work on the NFL’s career advisory panel to develop up-and-coming head coaches and general managers. He had also seen Bowles give a presentation at the NCAA Coaches Academy in 2014 and witnessed what he’d heard from many players: that Bowles is able to put complex ideas in simple terms that are easy to understand. In researching Bowles’ stint as the Dolphins’ interim head coach in 2011, Casserly became even more impressed.

He’d heard a story about how Bowles had once stopped a practice in Miami because the players weren’t going as hard as they should have been, and he started practice over from the very beginning. In his first team meeting as the Dolphins’ interim coach, Bowles laid out a clear vision of what he expected, right down to the number of times he planned to throw the ball in a game. If we reach that number in the first half, he told the team, we are not throwing it once in the second half. The Dolphins went 2-1 with Bowles at the helm.

“That itself should have been revealing,” Williams says. “To me, Todd Bowles should have been a head coach sooner.”

For years the Jets have been a complex team that Bowles has now simplified by establishing clear expectations. They expected a disciplinarian, and he made the team run gassers after a couple on-field skirmishes during training camp. They were told he was a master halftime adjuster, and his teams have outscored opponents 34-0 in the third quarter. His defense was stocked with top-shelf defenders at every level, and he’s delivered new wrinkles in every game, including switching to a 4-3 base last week to neutralize Washington’s power running offense and seamlessly mix in Richardson after his return from suspension.

This week, though, provides the biggest test yet. No one has been able to slow the highly motivated Patriots, who are steamrolling opponents and scoring an average of 36.6 points per game. For 11 of the last 12 years the AFC East has run through Foxborough, and the Holy Grail for every new Jets head coach has been to shift the power dynamics of the division.

Parcells texted Bowles this week, too, but it didn’t have anything to do with the Patriots. Bill Belichick, of course, is also a Parcells’ protégé. The Hall of Fame coach commented only on the win over Washington. “I liked everything but the blocked punt,” he wrote.

Though that late fourth-quarter miscue didn’t impact the outcome of the game, it was an egregious mistake. The Jets only had 10 men on the field for an end-zone punt that Washington blocked and recovered for a touchdown. Parcells hates disorganization, and so does Bowles, who took the blame for the mistake and then moved on to New England. The Jets are following their head coach, and right now, their head coach looks pretty good.

“We’ll see,” Parcells says. “He’s only a few games in. Don’t go putting him in Canton yet.”

• MORE MMQB:King on Denver | Tyrann Mathieu film study | Vikings Donut Club