The Play-callers: Why Bruce Arians’s ideas have Cardinals’ offense rolling

In this new series, SI’s Doug Farrar goes beyond the All-22 to explore the philosophies of the NFL’s best play designers. First up: Cardinals head coach Bruce Arians.

“Every day is a blast. I’m not coaching for my next job; this is it. This is it, so I do whatever the hell I want to do.”

That’s what Cardinals coach Bruce Arians told me last season about his overall coaching philosophy, and it’s a big part of why the 63-year-old has not only been successful in his first full-time head coaching gig but is also enjoying a bit of a renaissance late in his coaching life.

Blanket Coverage: Broncos’ O-line is a long way from its early uncertainty

This is, after all, the same offensive coordinator the Steelers chose not to re-employ after the 2011 season. At that point, Arians was fed up with the politics of the game and might have been on his way to becoming the next big name in the industry of tutoring draft-eligible quarterback prospects before Chuck Pagano called him later in 2012 and offered him the Colts’ offensive coordinator job.

What happened from there has been told many times: Arians took over in Indianapolis after Pagano was diagnosed with leukemia, put rookie quarterback Andrew Luck in a position to succeed, was named the Coach of the Year, and then was hired by the Cardinals as their new head coach in January 2013. Arians put up double-digit wins in his first two seasons in Arizona despite various personnel issues, and this year he was given a contract extension this year through the 2018 season.

At 6–2 heading into Week 9, Arians’s current team may be his best shot yet at the Super Bowl. The Cardinals rank third in offense and third in defense in Football Outsiders’ opponent-adjusted metrics, and although first-year defensive coordinator James Bettcher has done a great job of expanding upon the blitz and coverage concepts put in place by Todd Bowles before Bowles became the Jets’ head coach, the real star of this show is Arians and his offensive philosophy. Arians and general manager Steve Keim are in lockstep with each other on how this offense should look, and with a healthy Carson Palmer at quarterback (and yes, the team’s success is based to a large degree on Palmer’s health), this is as effective, diverse and entertaining an offense as you’ll see in the NFL.

Not that it’s been easy. Before rallying for a Week 8 win over the Browns, the Cardinals faced a 10-point halftime deficit, and Arians raked his team over the coals at the half—he was not amused, and he let everybody know it. Then, as good coaches do, he put the pressure on himself to make things better for his players. Palmer threw three touchdown passes in the second half, and the overwhelmed Browns defense shut down.

The standard definition of good play-calling is exploiting the best matchups, but according to Palmer, it goes deeper than that.

NFL Power Rankings Week 10: Top NFC North team isn’t the Packers

“It wasn’t the game plan, it was his timing,” Palmer says. “He was just on point with his calls. It’s the same game plan we’ve had. I was speaking more of just when he was calling certain things. When he was calling screens, we were gashing them. When he was calling [deep] shots, the shots were there. The run-game calls were spot on. It was just kind of one of those days where he was just really in a good zone. And he was in it in the first half too, we just weren’t executing on it. We had some turnovers that cost us on some drives. But he just really seemed to have a really good feel. As players have really good games and they’re kind of in the zone, that same can be said for coaches. And I think BA was definitely in a groove there.”

Arians has found a groove quite often during his time in Arizona, and he'll need to be so again when the Cardinals take on the Seahawks on Sunday night. The larger question is: How does he do it?

Giving his quarterback a piece of the action

The 2014 Cardinals started out 8–1 before Palmer tore his ACL and was lost for the season. With Ryan Lindley and Drew Stanton as backup quarterbacks, Arizona backed into the postseason with an 11–5 record and was eliminated in the wild-card round by the Panthers. But Stanton’s success in relief underscored a common pillar of Arians’s success in different places: his ability to groom quarterbacks who know his scheme and then give them a stake in the game. Arians has an absolute belief in his ideas of offensive structure, but he’s also willing to listen to his quarterbacks.

Start ’Em, Sit ’Em: How to set your fantasy lineups for Week 10

“Early on, and I think if you ask any player, regardless of position, confidence is the hardest thing to hold onto and the easiest thing to lose,” Stanton told me last November. “You start questioning and doubting yourself, especially when people try and tell you that you can’t do things. But he’s done a great job of re-instilling that in me, and that started in Indianapolis. He gave me the ability and freedom to do stuff, even though I was a backup. He listened to my input and made me feel that I had a voice, even when I wasn’t on the field. So now, when I get on the field, I feel very comfortable with what’s going on, the mechanics of things. He’ll chime in on certain throws—get my shoulder down, do this, do that. Having played the position too, I think he understands the cerebral part of that. He can relate to quarterbacks and help them to feel relaxed and confident.”

It seems like an obvious goal to make the quarterback feel involved and comfortable, but anyone who’s watched the restrictive play concepts in Green Bay, Seattle and other places where frustrated offense is the order of the day know how quickly that can fall apart. Less confident or inexperienced play-callers tend to impose their systems on their players, regardless of their skill sets. This week, Palmer echoed Stanton’s thoughts about Arians’s ability to bring other voices to life.

“Obviously, being around him for three years and just hearing his input on certain plays and certain coverages,” Palmer says. “A scheme comes up and we’re working on a scheme and he might change his mind, and he’ll give you a reason why. He doesn’t just change a certain route within a scheme or put something new in, there’s always a reason behind it. So he’s always giving you insight. He’s brilliant offensively. He’s as bright an offensive mind as I’ve been around. So just having a chance to be around that type of guy just enlightens you on tons of things that you don’t know about. Being in year 13, there’s a lot I don’t know. I still am always trying to learn, and being around a guy like him just accelerates the process. I’ve just learned a ton about football. A ton about offense, and a ton about protections, and coverages, and really just everything through him.”

Of course, that’s nothing without players who can implement the concepts, and the Cardinals are certainly doing that this year. The most impressive part of Arians’s passing game is the diverse ways in which he sets up the vertical attack.

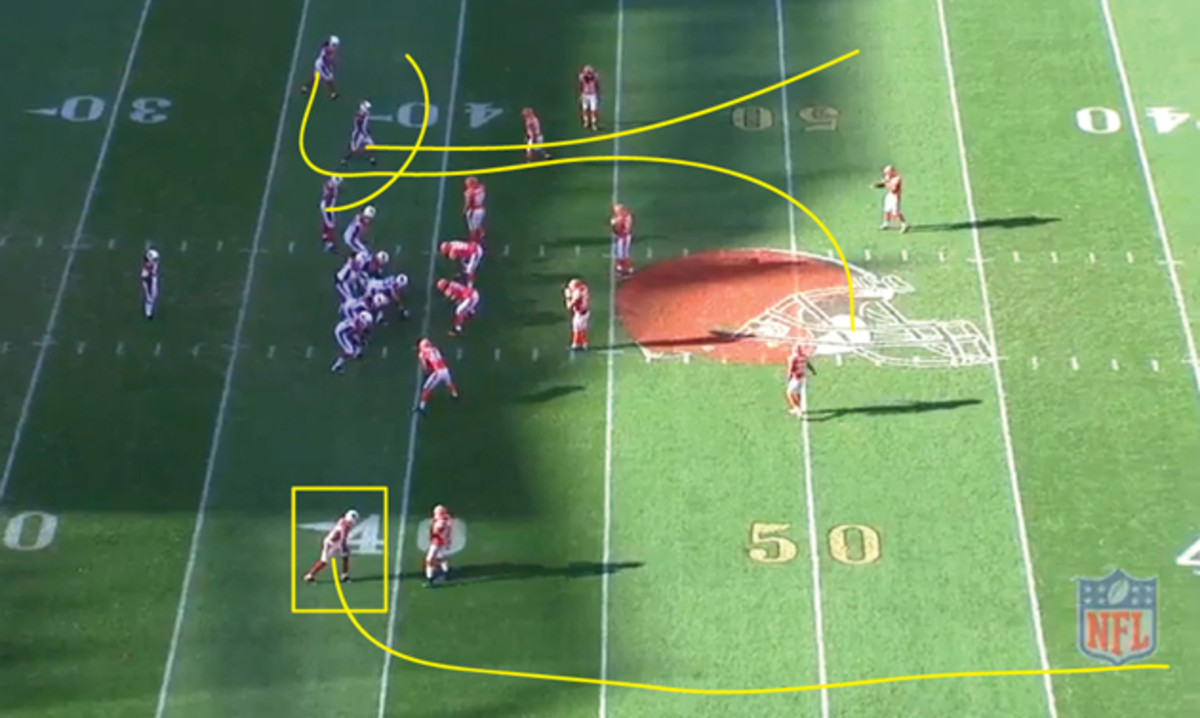

A diverse downfield attack

One concept common to Arians’s philosophy no matter the down or formation is a little wrinkle on the vertical passing game: He likes to set up an opportunity for a first down on one side of the field and an opportunity for explosive play on the other side. This idea goes all the way back to Sid Gillman with the old AFL Chargers of the 1960s, and it sets the quarterback up favorably in two ways. If he’s got the personnel advantage on the deep side, he can take that shot. If not, there’s a checkdown or relatively easy first or second read to target. Thus, Palmer isn’t reliant entirely on deep isolated routes; his coach is setting up open receivers underneath if he needs it.

The All-22: Packers’ problems on offense rooted in a limited playbook

“Yeah, I mean, it’s not just everybody run a go [route],” Palmer says. "There’s always player control and something underneath the route for every coverage possible. So it’s not just hey, let’s just take a big, long seven-step drop and everybody run a go. There’s always ways to check the ball down and get the ball out of your hands quick, and make a defense turn and recover to the ball.”

Palmer’s 60-yard touchdown to Michael Floyd in the third quarter of the Browns game is a good example. He had Floyd as the right-side boundary deep receiver, but he also had Larry Fitzgerald on a shorter crossing route if he needed that. Contrast that with the lack of easy openings you often see in other offenses (yes, we're talking about you, Packers).

Again, one primary aspect of Arians’s connection with his quarterbacks is his insistence on involving them in the play design. Whether it’s deep backside crossing routes or slant/vert combos over the middle, Arians wants his field generals to own the plays they’re calling.

Linval Joseph a main reason why resilient Vikings continue to rise

“I think the one thing we always have done with all our quarterbacks is they’ve really called the game,” Arians said this week. “Friday, we’ll sit down and pick out his 15–20 favorite first-and-10 plays. Saturday night before the game, we’ll sit down and go through the entire third down package and let him pick the plays, the ones he’s most comfortable with. I can call what I think is the greatest play, but if he’s not comfortable with it, it’s probably not going to work. My job is to talk him into running those once he sees the picture on the sideline. He’s a veteran guy who works extremely hard, and you just, as a coach, try to put him into a position to be comfortable and successful.”

Again, this sounds like common sense, but it’s not as common as you may think. Another uncommon (and highly successful) aspect of Arians’s philosophy is his need to keep defenses off balance. He in no way subscribes to the “Line up and see if your guys can beat our guys” approach—Arians always wants to be at least one step ahead.

Schematic diversity

It’s Arians’s firm belief that an offense that’s easy to recognize is easy to defend, and he wants no part of that. So, you’ll see multiple vertical routes out of two- and three-tight end packages, draws out of wide formations, multiple short routes out of empty formations when other teams would go deep ... on and on. And Arians is especially attuned to throwing things at defenses they either haven’t seen before or are specifically ill-equipped to defend. Arizona’s offense doesn’t have one central approach, which in itself is a central approach.

“I don’t think there’s any doubt,” Arians said of the value of that diversity. “Two things: you have to be able to run the ball and stay two-dimensional, but you also want to be able to have enough things in your offense this week that they didn’t practice on Wednesday and Thursday.”

'I'm going to Disneyland!' How simple phrase became Super Bowl lore

Palmer benefits from that more than anyone.

“Yeah, I think that’s what makes him hard to defend and makes us hard to defend,” Palmer says. “There aren’t a bunch of tendencies that you see on film where you know a certain play’s coming. He’s very, very careful in designing plays and designing a game plan with what’s on film from the previous month or two. He always tries to keep you guessing. One week it will be a whole bunch of runs out of one formation. The next week it’ll be all passes. So he makes it really tough to find a tendency in what he’s doing.”

And when it comes to overall philosophy, the best football philosophers have that skill in common: Keep your opponent off-balance and force them to react to you. Arians has it in spades, and it’s why he and the Cardinals are an ideal match.