The All-22: Packers’ problems on offense rooted in a limited playbook

Before the Packers faced the Broncos two weeks ago, reactions to Green Bay’s early-season offensive malaise varied from little alarm at all to “Well, they'll get it fixed.” After all, the Packers’ offense started the 2014 season off slowly before Aaron Rodgers told everybody to “R-E-L-A-X” and led his team to within a few highly improbable plays of a trip to Super Bowl XLIX. But what Denver’s top-notch defense did to Rodgers was quite unprecedented: The reigning MVP was limited to 77 yards passing and 14 completions on 22 attempts. Denver pressured Rodgers on 63% of his dropbacks (per ESPN Stats & Info), the highest pressure rate he’s had in the last seven seasons, and he completed 6 of 12 passes under pressure for 35 yards.

Then again, going 8 of 10 for 42 yards when not under pressure isn’t exactly world-beating either, and it speaks to a problem that goes far beyond Rodgers’s ability to deal with pressure. Pressure has never been an issue for Rodgers—throughout his estimable career, he has excelled when forced to leave the pocket.

Rex Ryan’s choice of captains for game against Jets no laughing matter

“Schematically, we need to do some different things, and execution-wise we need to get open and complete passes,” Rodgers said after the 29–10 loss, Green Bay’s first of the season. “When you are playing a good cover team like that, we had some ideas, and we didn’t convert them.”

The obvious problem that shows up more and more on tape: a limited palette of routes that leaves Rodgers with very few options. When you face an aggressive press coverage team like the Broncos, who can create pressure without deploying extra defenders, moving through a game with a bunch of slow-developing isolation routes is a recipe for disaster.

It’s something that Rodgers has touched upon throughout the season, and it mirrors the problems early on last season. Green Bay’s slow offensive start in 2014 was predicated on an overall lack of formation diversity and an assemblage of route concepts that left Rodgers without easy openings and short-to-intermediate coverage-beaters. This season, with No. 1 receiver Jordy Nelson already out for the season due to a torn ACL and second receiver Randall Cobb struggling with all kinds of maladies of his own, it’s safe to say that coach Mike McCarthy and de facto offensive coordinator Tom Clements are doing Rodgers no favors at all with the backups, and it’s as mystifying now as it was then as the Packers look for ways to stop their current two-game losing skid.

The Stats

When I wrote about Green Bay’s stagnant passing offense early last season, the Packers’ primary issue was a constricting sameness in their formations. According to charting metrics from Pro Football Focus, the Packers had run “11” personnel—one running back, one tight end and three receivers—on 76.6% of their plays. It was a major increase in one personnel package for the Packers and a huge bump over the league average of 51.4%.

On The Numbers: Williams's standout day, a perfect week for PATs, more

This year, not much has changed. Through Week 9 of the 2015 season, the Packers are running “11” personnel packages on 75% of their snaps. The league average is 55%.

The most intriguing thing about the sameness of Green Bay’s sameness is that McCarthy ceded the play-calling responsibilities to Clements after that NFC Championship Game loss to Seattle, citing a need for a more general view of his team.

“I would say my role is more in line with more traditional head coaching responsibilities with being involved in all three phases and focusing on the areas of self-improvement, so that’s how I would describe it,” he told me in September. “A big part of my job as head coach is the interaction with the assistant coaches. Whether it’s on scheme, scheduling, or emphasis of the things we are always trying to improve on.”

Key storylines to follow in continuing saga of daily fantasy sports industry

Through nine weeks, this isn’t working, and it shows up in all kinds of ways. Rodgers’s deep passing numbers are way down, which isn’t what you’d expect in an offense short on quick route openings. Per PFF, Rodgers has completed 10 of 25 passes over 20 yards in the air for 317 yards, two touchdowns and no interceptions. For perspective, Jacksonville’s Blake Bortles leads the league in deep attempts (62), completions (26), yards (835) and touchdowns (six). Last year’s slow start had a similar effect on Rodgers’s numbers by this point: Through nine weeks of 2014, Rodgers had completed just 9 of 18 deep passes for 418 yards, five touchdowns and no interceptions. Not bad, but not what one would expect from Rodgers. The Packers turned it around late, and Rodgers’s 2014 totals on deep balls, including the playoffs, were pretty formidable: 29 completions in 69 attempts for 1,092 yards, 13 touchdowns and two picks.

When under pressure, Rodgers ranks 22nd in completion percentage (47.4%), with 37 completions on 78 attempts, eight touchdowns and one interception. Philip Rivers leads the league in completion percentage under pressure (68.1%), and Rodgers’s high touchdown-to-interception ratio under pressure actually speaks more to his ability than anything in Green Bay’s playbook. Basically, Rodgers is forced by a simple overall offensive philosophy to play outside of structure, and that’s when things open up for him and his receivers. That’s a testament to Rodgers’s abilities, but it’s not a sustainable way to power an offense.

The Tape

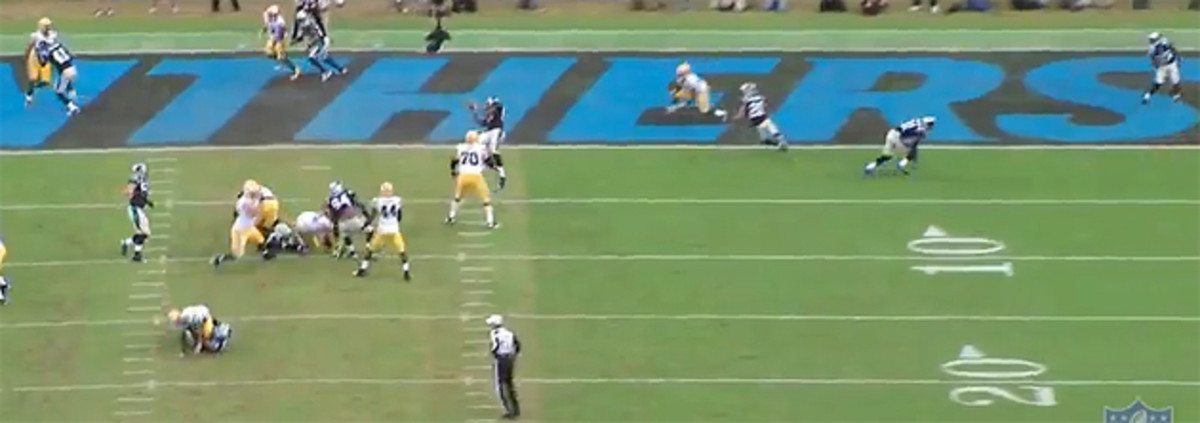

Some see Rodgers’s Week 9 performance as a return to form, but it really wasn’t; it was more about some playmaking in the second half and the Panthers’ preference to play zone defense. In the 37–29 loss, Rodgers completed 25 of 48 passes for 369 yards, four touchdowns and one interception, and had the Packers driving down to potentially tie the score late in the game. We’ll start our tape study with the play on which everything fell apart.

Waiver Wire: Patriots RBs become hot commodities with Lewis injured

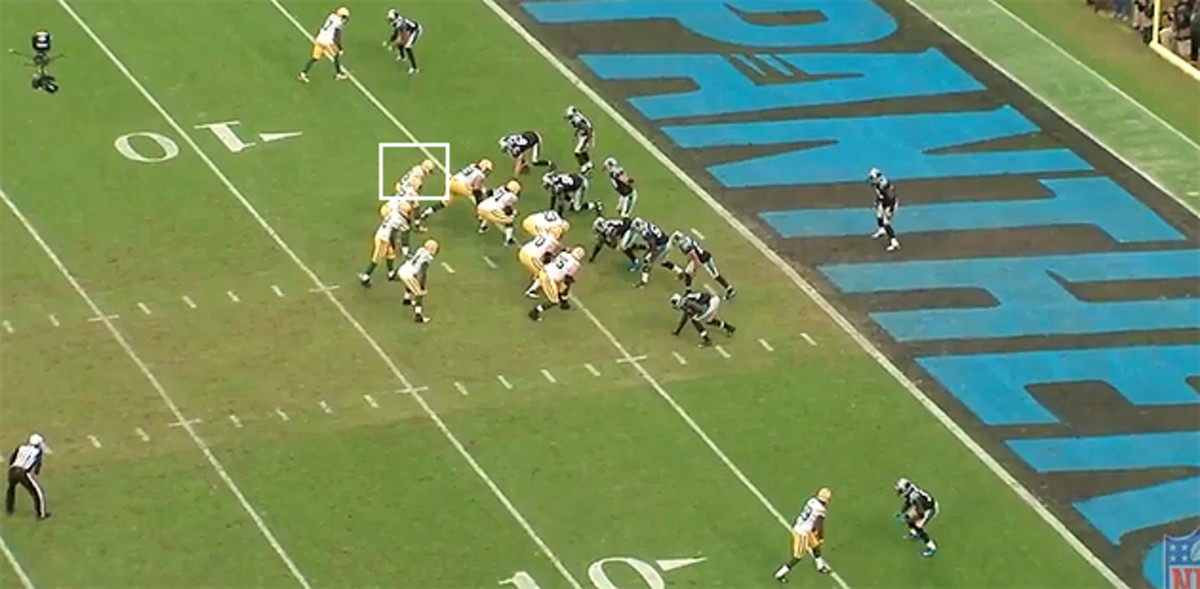

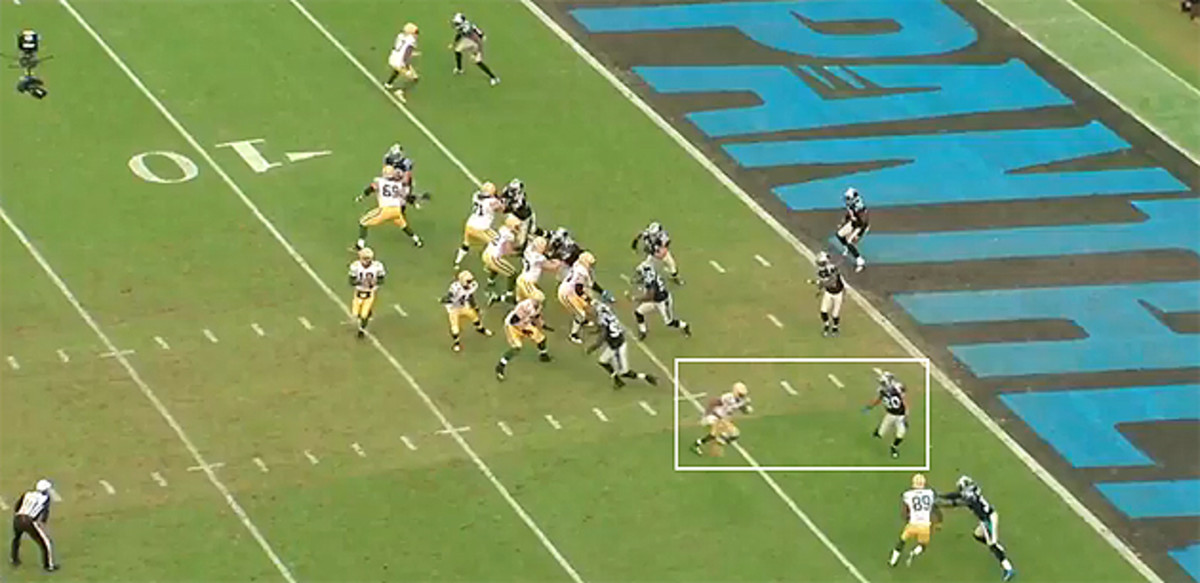

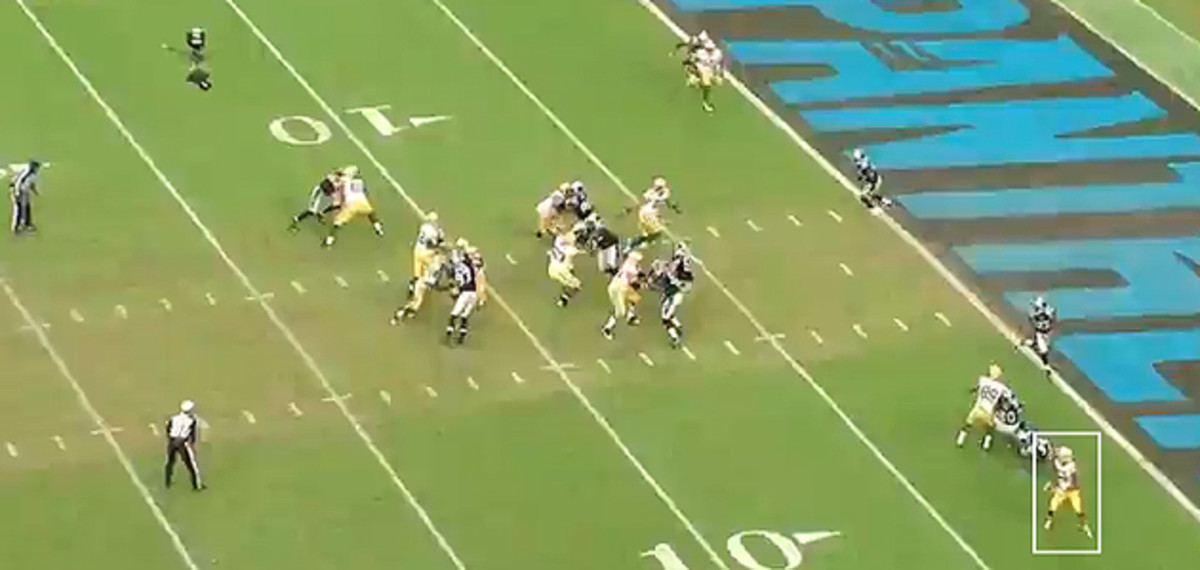

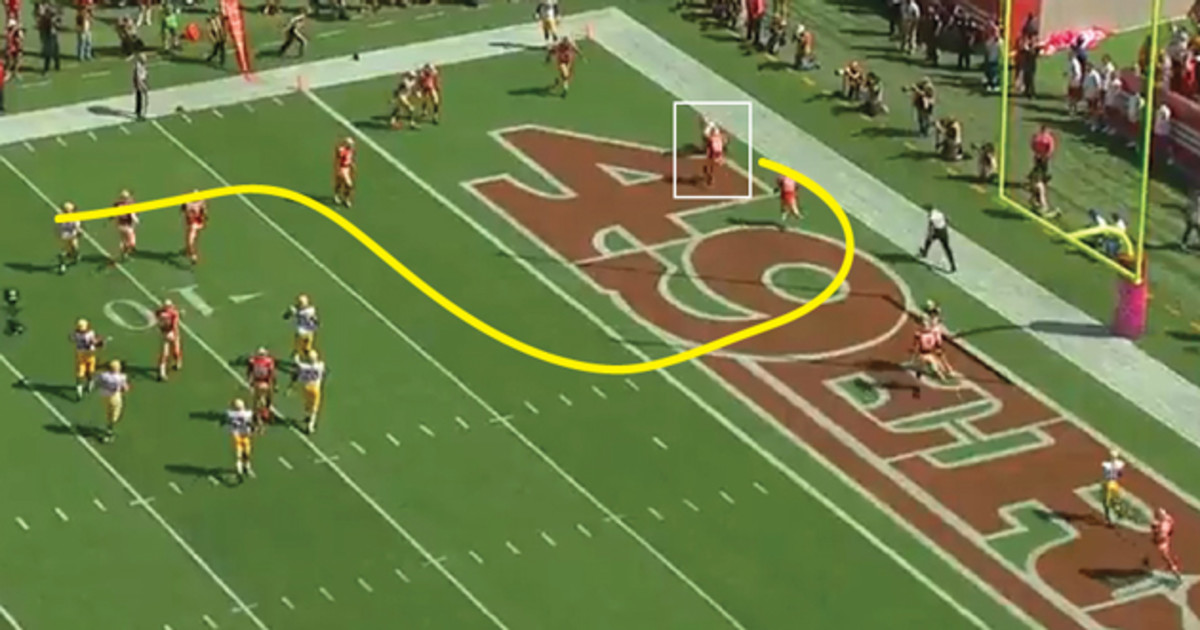

The Packers had the ball at the Carolina four-yard line with 2:00 left in the game, and the opportunity to tie the game with a touchdown and two-point conversion. Green Bay lined up with two wide receivers and three players—tight end Richard Rodgers, halfback James Starks and Cobb—in the backfield. Pre-snap, Cobb rolled right in a long motion to run a rub play with right outside receiver James Jones. That happened, but the route developed so far away from Rodgers (who was under pressure from defensive tackle Kawann Short) that he never saw Cobb wide open in the right side of the end zone. Instead, he threw up a prayer of a pass that linebacker Thomas Davis intercepted for the game-clincher.

“It was a great call,” Rodgers said after the game. “I looked out to [Panthers cornerback] Peanut [Tillman] to see if he had eyes in the backfield, because I was worried about him sloughing off and him tackling Randall short of the goal line. Turns out [Jones] kind of ran Peanut into [safety Kurt Coleman] and Randall was wide open for the touchdown, so that’s disappointing.”

Perhaps most disturbing is Rodgers’s admission that he was “scared by something.” That could have been the pressure up the middle, caused by some questionable blocking in Green Bay’s full-house backfield, but it’s not what you want to hear from your future Hall of Fame quarterback.

“I had the easy opportunity there for a pitch-and-catch touchdown but I got scared by something," Rodgers concluded. "I can't explain it. It was a mistake by myself. I will definitely be thinking about that one on the ride home, but we have to move on tomorrow and get ready for this divisional stretch. The last play is very disappointing.”

The more you look at them, the more you see how unhelpful Green Bay’s route concepts are for Rodgers. Aside from the occasional rub or stack formation, you don’t see a lot of stuff designed to present Rodgers with an easy open read, or his receivers with schemed formation advantages. Green Bay’s passing game seems designed to succeed three ways this year: Rodgers throwing deep off of free plays after he’s fooled the defense into jumping offside, extending plays outside of structure and exploiting one-on-one iso matchups.

NBC’s Collinsworth on how he handled Greg Hardy during Cowboys-Eagles

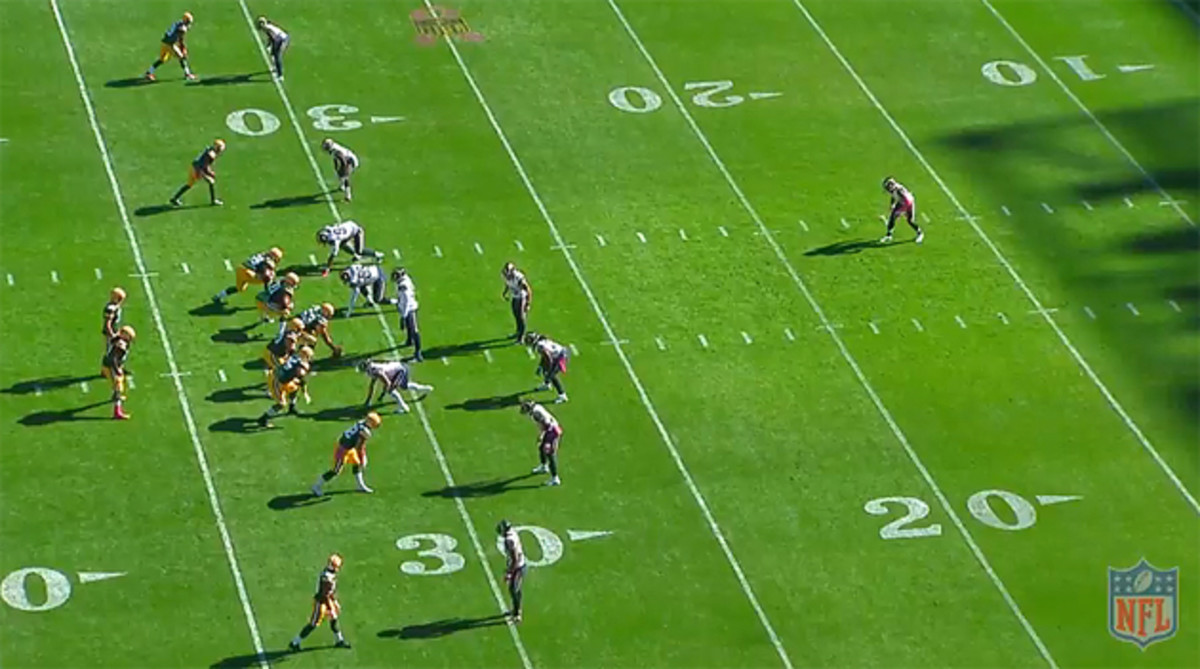

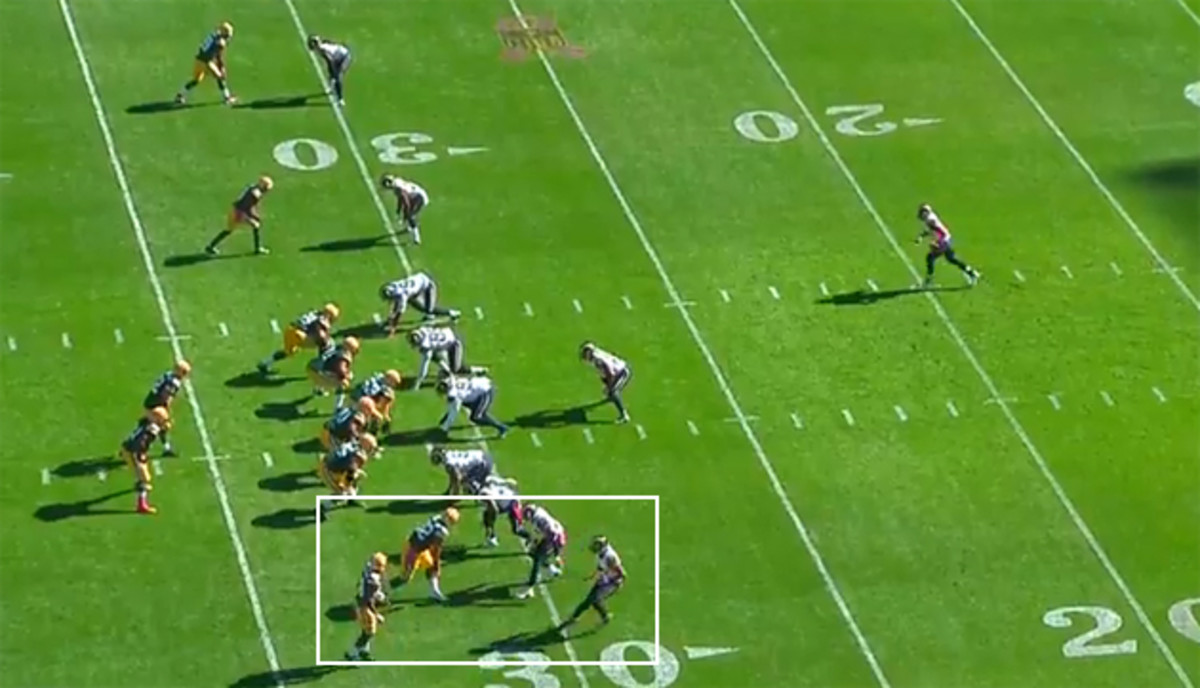

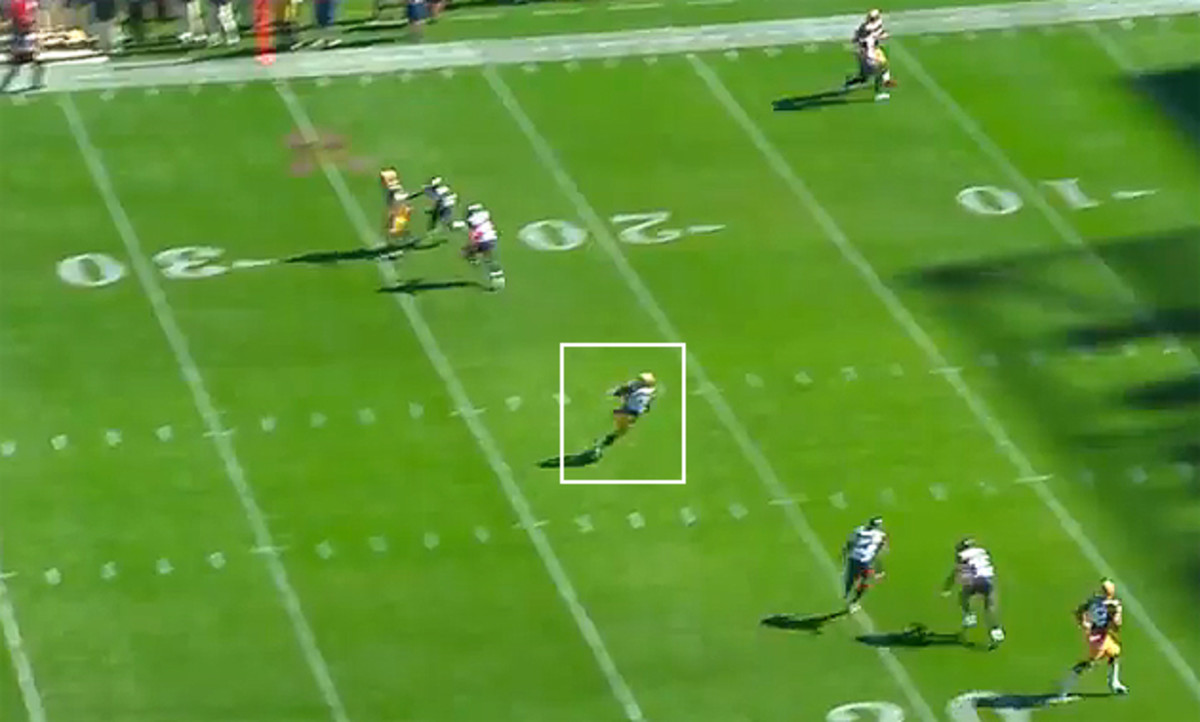

There’s enough on tape to show how much else could work. Both of Rodgers’s touchdown passes against the Rams in a 24–10 Week 5 win were based on the same motion-to-Twins stack concept. St. Louis found it impossible to defend, but we’ve rarely seen it from the Packers since. Here’s the first of those two touchdowns, with receiver Ty Montgomery motioning inside pre-snap to align with Richard Rodgers in the slot. This revealed that the Rams were in man defense and forced St. Louis’s cornerbacks to play from a spatial disadvantage. Without coverage help up top, the chances were high that one of their defenders were going to lose big on a crossing route. And that’s exactly what happened when Montgomery cut inside and cornerback Trumaine Johnson and safety T.J. McDonald both went with Rodgers instead. Safety Rodney McLeod went to the other side to help cover Cobb in the left slot, and that was the ballgame.

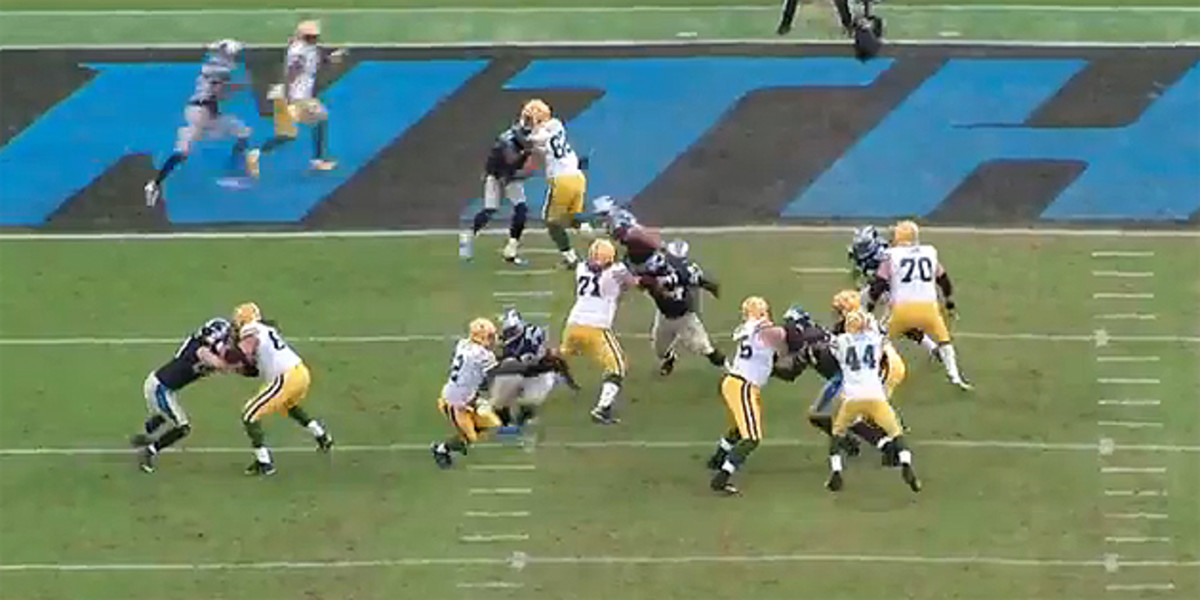

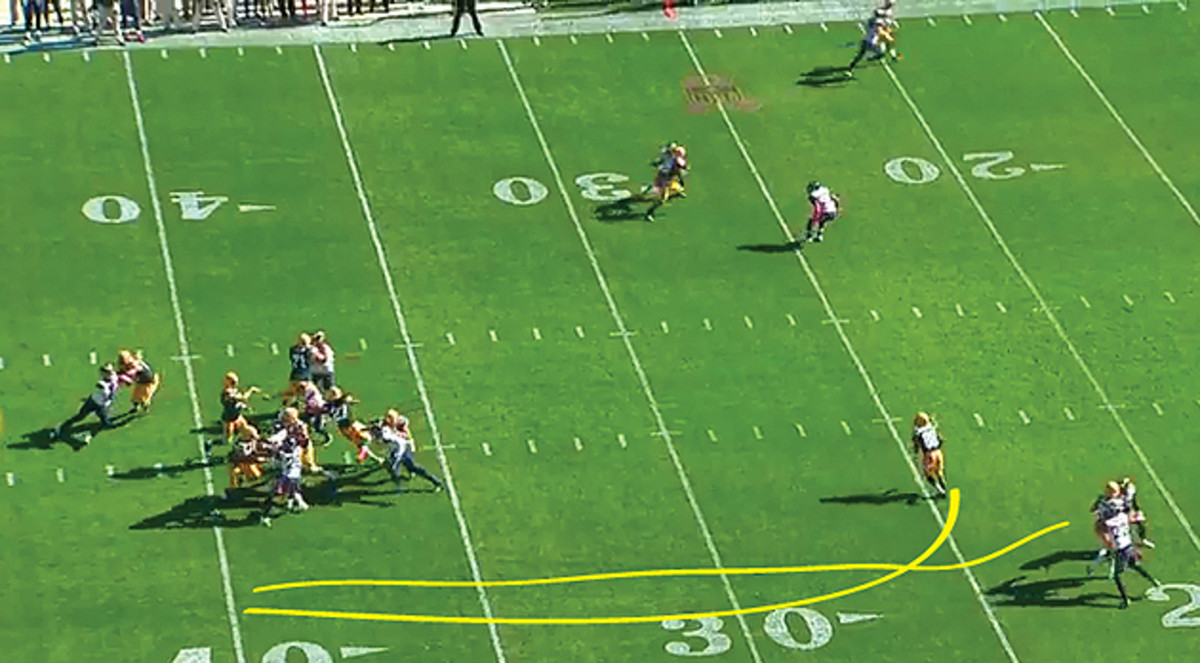

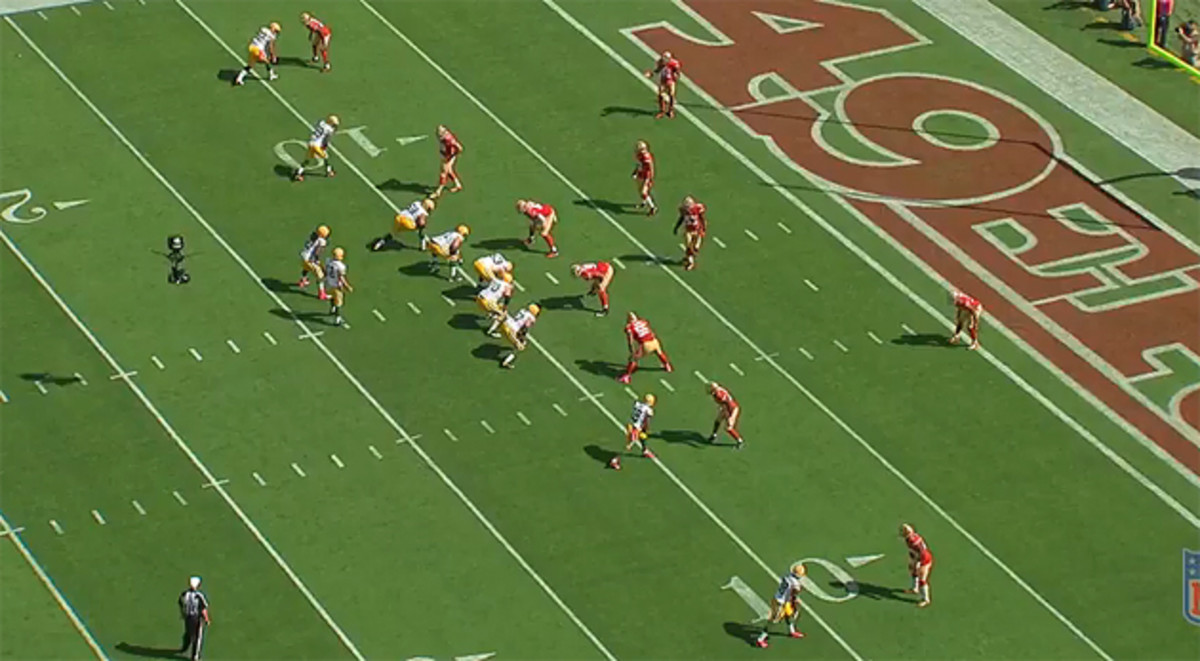

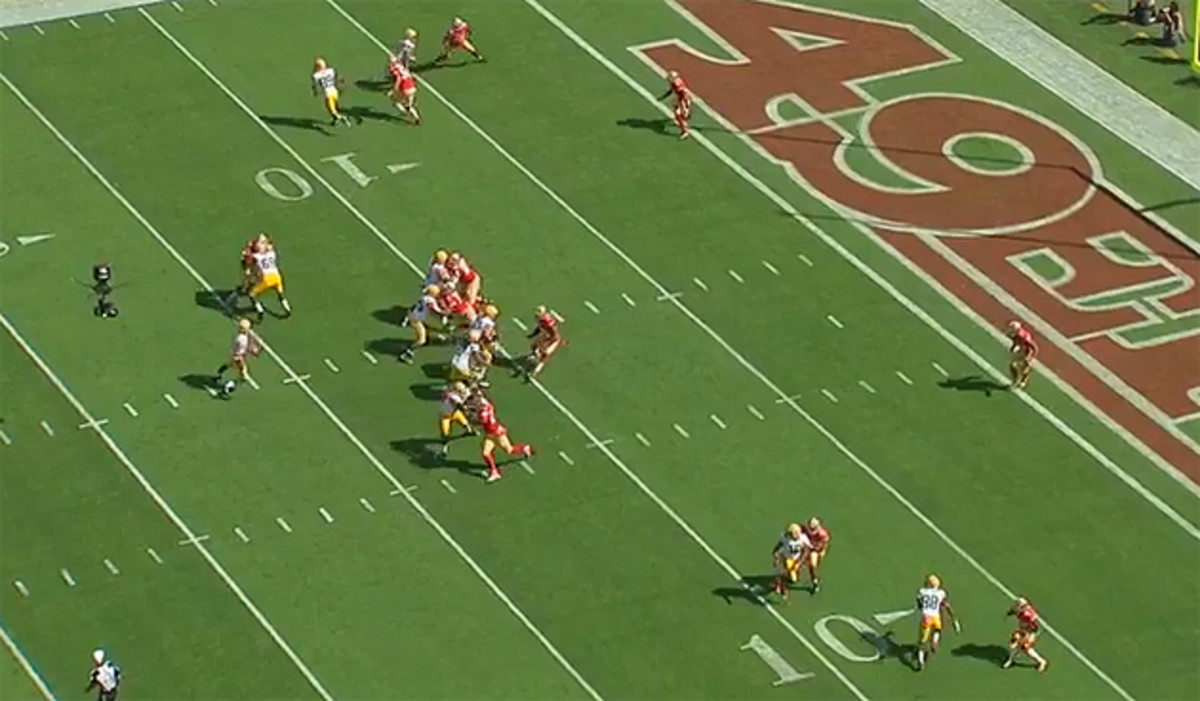

So, the question stands: Why don’t the Packers use more man-beaters and crossing concepts, especially against teams that play a ton of aggressive man coverage—like, say, the Broncos? That answer is locked somewhere in the Green Bay front office, but what we do know is that as it’s currently constructed, the coaching staff relies too much on Rodgers’s ability to extend plays beyond their planned breaking point and work outside of structure at the same time they decry the whole idea. This touchdown pass in the first quarter of Green Bay’s 17–3 win over the 49ers in Week 4 was an optimal example. Rodgers was under a ton of pressure through most of the game, and while it’s true that Green Bay’s offensive line hasn't performed up to its standards this season, you can also see a lot of coverage pressures on Packers tape this year. And that’s got a lot to do with play design.

As you can see in the second screengrab, Rodgers sees nobody open on the dual slant-flat combo when he turns to make his reads. He then misses James Jones coming open for a second to the right outside set and starts to scramble to his left. Twice, Rodgers bails out of pressure, and the touchdown pass goes to Richard Rodgers, who extended his route through the chaos and beat safety Antoine Bethea in the end zone. Is it on Rodgers for missing Jones? Absolutely. But you see quarterbacks start to close up their reads at times as a cumulative effect of openings closing too quickly or failing to exist at all, and I think that’s what’s going on here.

Sour Rankings: Talib poked Allen's eye, Tannehill botched another snap

“I’ve never gone into a game with a goal of calling 30, 35 plays and six plays we relied on production from the scramble phase,” McCarthy said earlier this month. “The scramble phase is really a reaction to what’s going on between the offense and defense. We don’t call plays and say, ‘OK, let’s just hold it for 2.5 seconds and then turn it into a scramble.’ That's not the way we operate.”

The Packers want their offense to be an execution-based offense in which players use their abilities to win personnel battles. That’s all well and good, but it could be argued in today’s NFL, execution-based offenses must also rely on schematic fortitude. The modern game is too complex to think otherwise, and without more diverse systems in place, an offense is behind the eight-ball before it hits the field.

It’s a glaring problem McCarthy and Clements must solve, sooner than later.