The Officiating Crisis: Worse than Ever, or Just Louder Critics?

“Referees of football and basketball games today are being accused of worse blunders than ever before.”—Sports Illustrated, March 26, 1962

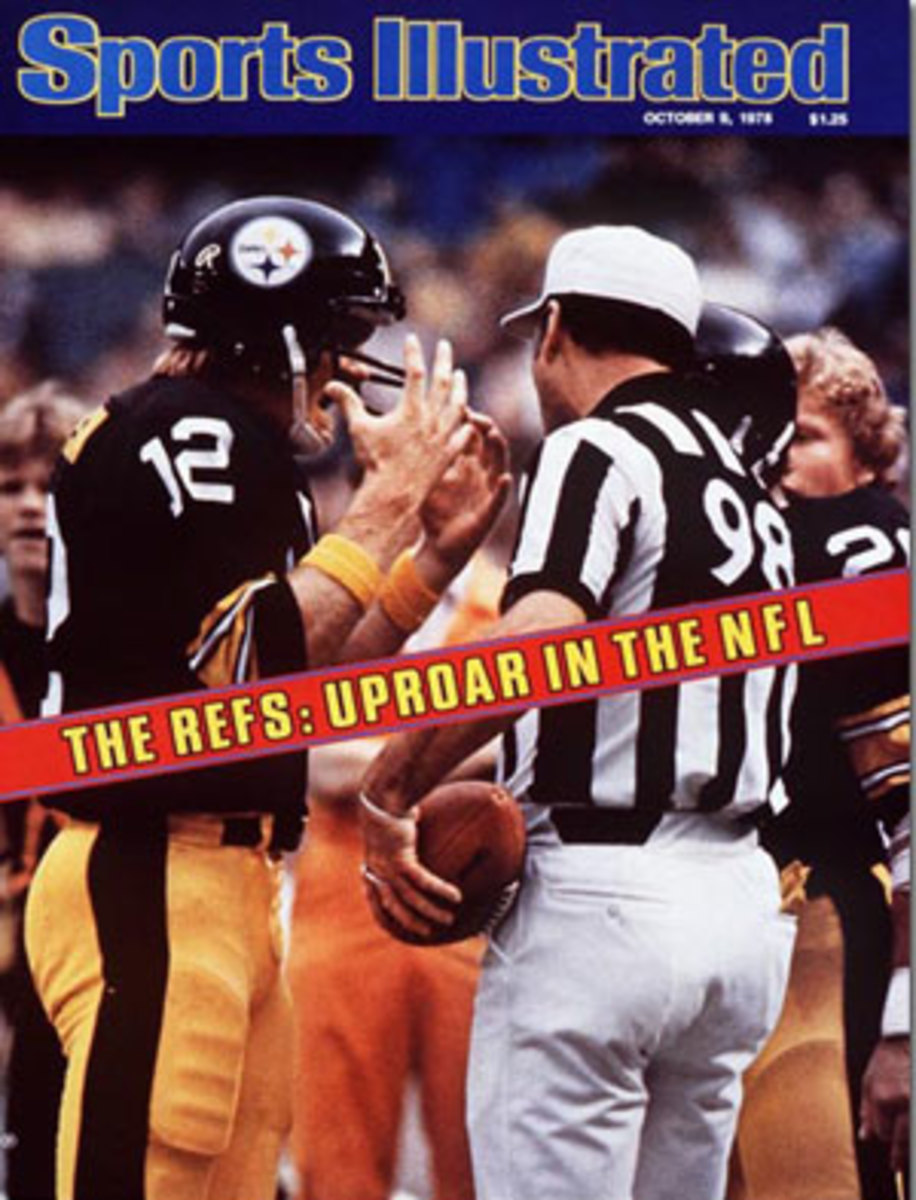

“It is hard to remember a season that produced such a rampant display of human fallibility as has been revealed—on television, always on television—by the officiating crews of the NFL.”—Sports Illustrated, Oct. 9, 1978

“Pro football has been victimized by incompetence this year.”—Los Angeles Times, Nov. 6, 1996

“Criticism of NFL officials has seldom been as vociferous as it has been this season.” —USA Today, Dec. 1, 1998

“Regular Officials Back, and So Are Complaints.”—New York Times, Nov. 12, 2012

These are the end times, once again.

One month until the playoffs, and the chorus of criticism over NFL officiating that has faded in and out for decades has hit another crescendo. The griping over costly mistakes got so loud this season that the NFL was forced to act. On Wednesday, Dean Blandino, the league’s vice president of officiating, announced that during this year’s playoffs the lines of communication between the referee on the field and the NFL’s New York officiating command center will be widened beyond instant replay. Game officials will now be able to consult Blandino or his representative on issues such as assessment of penalty yardage, the game clock and other “administrative” matters, though Blandino said New York will not be calling penalties, changing fouls or otherwise getting involved in judgment calls that aren’t in the purview of replay.

A well-placed officiating source told The MMQB that these “consultations” have already been going on with select crews this year, suggesting that even before this season’s series of high-profile gaffes that outraged coaches and fans and undermined credibility, the league knew it had to do something to address the state of officiating.

And yet it sure feels like we’ve been here before. Here’s NFL spokesman Greg Aiello, in 1997, talking to the Dallas Morning News: “Every year at about this time we start hearing about how bad [officiating] is. It’s an annual event, like Groundhog Day.”

So which is it—an unprecedented crisis, or a Bill Murray time loop, with criticism now amplified through the bullhorn of social media? The MMQB analyzed statistics, delved into policy and interviewed former NFL officials, current players, coaches and front-office personnel to answer two burning questions: Is officiating actually worse than it’s ever been? And how can the league make officiating better, and snap out of its recurring nightmare?

* * *

A quick recap of The MMQB’s survey on the state of officiating, before we dive in.

Former NFL referee Mike Pereira: “I don’t think there’s anybody outside of Blandino and [Roger] Goodell who would say the officiating has been as good as it was before.”

Seahawks cornerback Richard Sherman: “They criticize the refs the same way people criticize players. You watched it in slow motion; I experienced it in full speed.”

Sherman’s teammate, defensive end Michael Bennett: “[Officials] don’t seem to be upheld to any standard. The players are noticing it’s worse, and so are the fans. They’re causing people to lose games.”

Ben Austro, Editor in Chief of the popular officiating website FootballZebras.com: “I definitely see that the quality is not what it was, but it’s not off by a lot. It’s not like this terrible epidemic social media might make you believe.”

A high-ranking AFC front-office executive: “I wouldn’t be able to say it’s worse, but I would be able to say I can’t remember when there was this much confusion or [this many] communication breakdowns.”

Former referee Gerry Austin: “There have been a few hiccups this year, maybe more hiccups than there have been in years past, but the whole system isn’t broken.”

Among the rash of mistakes, the NFL has publicly admitted to these prominent errors this season:

• In the Week 4 Detroit-Seattle game on Monday Night Football, the back judge failed to flag Seahawks linebacker K.J. Wright for illegally batting a Calvin Johnson fumble out of the end zone, a penalty that would have given the Lions, trailing 13-10, the ball on the one-yard line with under two minutes to play. Instead, the Seahawks got the ball and ran out the clock for the victory.

• In the Week 5 San Diego-Pittsburgh MNF game, the crew failed to notice the clock continuing to run after a touchback on a Chargers kickoff, costing the Steelers 18 seconds on their critical final drive.

• With under five seconds to play in the Week 10 Jacksonville-Baltimore game, the officials missed a false start penalty on the Jaguars that would have resulted in a 10-second runoff, ending the game. Instead, the Jags benefited from a face mask penalty on Baltimore and, with an untimed down, kicked the game-winning field goal.

• In the Week 11 Bill-Patriots game, the official along the sideline failed to stop the clock when Sammy Watkins went out of bounds untouched with two second left, costing Buffalo a chance at a game-tying Hail Mary. That game also included an inadvertent whistle that negated a potential long gain on a Danny Amendola reception in the third quarter.

While the social-media pulse on Sundays and Monday nights would imply that the quality of officiating is at an all-time low, Blandino says that officials have not been measurably worse than past years. Earlier this month in his weekly video, he said officiating crews were averaging about 4.3 mistakes a game, roughly the same rate as the past 10 to 15 years. “We’ve had high-profile situations, mistakes in high-profile games, and that generates more discussion,” Blandino told The MMQB last week. “With where we are today as a society with social media and instant access and instant ability to comment and critique and debate, it’s created a narrative.”

“Every time they try to implement a point of emphasis,” says Goldson, “they exaggerate that and miss other penalties.”

The NFL keeps its grading of officials private, and it is difficult to quantify missed penalties or misapplications of the rules. In terms of the number of calls being made, teams are averaging 14.1 accepted penalties per game, the highest total through 14 weeks in more than a decade. But such numbers must be understood in the context of the league’s ambiguous and amorphous “points of emphasis,” perhaps the biggest factor governing the rise or fall in particular calls—and contributing to confusion amongst players and fans. The term refers to the officials’ focus on specific rules during a season, either for clarity or to pursue NFL policy. The changing points of emphasis from year to year help explain why it suddenly seems that previously overlooked fouls are being called far more frequently, and they help justify fines for plays that run counter to the growing emphasis on safety. The NFL’s penalty tallies represent myriad fluctuating emphases that players believe push and pull at one another.

For instance, according to league data, flags for illegal use of the hands spiked from 2013 (103) to ’14 (233), as did defensive holding (from 226 to 346) and offensive pass interference (75 to 142). “Every time they try to implement a point of emphasis,” says Washington safety Dashon Goldson, “it seems like they exaggerate that for that year, and miss other penalties. Last year with pass interference it got outrageous.”

That opinion was popular among players The MMQB interviewed—and was roundly rejected by former referees, exemplifying the clear split between the officials and the officiated on nearly all matters.

* * *

The NFL has 122 officials. Only one of them, Carl Johnson, is a full-time league employee.

Echoing a common refrain among critics proposing ways to improve officiating, Washington coach Jay Gruden says, “Make officials full-time. Really let them study the game and game trends, because there are a lot of things that make us question whether or not they understand the rules.”

Nearly six years ago, Mike Pereira tried to do just that. Shortly before retiring as vice president of officiating in April 2010, Pereira arrived at league headquarters in Manhattan with a Powerpoint presentation outlining his proposal to make 17 referees full-time employees of the league and create a training center where zebras could convene to discuss rules changes and interpretations, undergo evaluations, train and work with teams. He called his imaginary ref hub the Officiating Institute.

“They basically laughed me out of the room,” Pereira says. “It was disappointing. I was proud of my little Powerpoint. I did make sure that Goodell got a copy, but it’s probably still sitting under a stack of papers somewhere.”

While the idea makes sense in theory, creating a cadre of full-timers may be not be practicable. Start with an often-overlooked aspect of such an idea: Do current officials even want it? Most have other careers, some lucrative (attorneys, CEOs, bankers), others stable (teachers, college officiating supervisors, law enforcement). Ed Hochuli is a partner at a Phoenix law firm. Referee Gene Steratore and his older brother, Tony, a back judge, co-own a sanitary supply company. “We haven’t conducted a poll anytime recently,” says Jim Quirk, the executive director of the NFL Referee Association, “but from what I know about the 122 guys in the league—I will say not everyone, but a large majority would refuse the opportunity to become full-time.”

• GAME 150: A Week in the Life of an Officiating Crew

But the most significant hurdle may be not be the men in stripes themselves but the fine print of the collective bargaining agreement. The CBA that was signed after the 2012 lockout and that extends through 2020 includes a provision that, absent NFLRA consent, the NFL can hire no more than 17 game officials as full-time employees. (The sole current full-timer, Johnson, was Blandino’s predecessor before stepping back onto the field in 2012.) “We need to work through some of those issues, some of the labor management issues,” says Blandino.

The NFL began interviewing other full-time candidates in 2013, but the NFLRA threw a challenge flag. It turns out the league and union differed on a most basic principle: how to define employment. To wit, the NFL considers its workers to be at-will employees—“they can terminate you if they don’t like the way you comb your hair,” Quirk says—while NFL officials must be members of the NFLRA, a union with inherent protections. Neither side was willing to cede on the issue, so progress ceased.

Even if the NFL did make one member of each officiating crew full-time, that hardly guarantees improved performance. Is spending all week studying the rule book and analyzing game tape going to help an official make a decision on a bang-bang play? And Austin, the 25-year NFL official and current ESPN analyst, adds, “Is there even enough for everyone to do on a full-time basis? They could study more, but I don’t think that’s the problem.”

* * *

Earlier this season, Quirk arrived at the league offices for meetings, and like Pereira he was armed with an idea. Quirk served 21 years as an official and spent three years training umpires before taking on his current role with the union. His son is an NFL back judge, and Quirk has the pulse of officials in the league. This, Quirk figured, was as good a time as any to tell the commissioner what he felt was the biggest hindrance to officiating in 2015.

“Roger,” Quirk said. “You have to simplify the rule book. It’s just too complicated. It’s too long. It involves too many exceptions to the rule.”

Rehashing the Dez Bryant play in the NFC divisional round is an exercise only Jerry Jones and Bryant himself would relish, but that infamous no-catch decision might be the perfect distillation of officiating frustrations in 2015. Consider the fallout from the Bryant incident: The NFL recognized there was a problem, tried to fix it, but in doing so just muddied the waters further.

As debate swirled as to whether Bryant had “made a football move” or “failed to complete the process of making a catch” when the ball came loose at the goal line in that January game in Green Bay, the NFL felt pressure to clarify what constitutes a catch. This offseason the league issued a 158-word explanation that shifted the burden from “making a football move” to the equally nebulous notion of “clearly becoming a runner.” The clarification has satisfied no one, and officials, players, broadcasters and viewers all remain flummoxed as to what a catch is. When people who’ve spent their entire lives playing or watching football don’t understand the rule for something as basic as a catch, the problem is fundamental. Says Bears wide receiver Alshon Jeffery: “It’s just confusing; it’s not consistent.”

“When I started in the league,” says Green, “it was, when it doubt, it’s incomplete.”

Perhaps it’s not the officials’ decision-making that’s to blame, but rather the clunky language they must abide by. Several ex-referees who spoke to The MMQB said the rule book is too couched in exceptions and nuanced language about what might possibly happen that could affect a decision, and not clear enough in its basic definitions. If each play is inherently complex, they suggest, make the rules governing those plays simpler. (Interestingly, the NFL rule book, at roughly 58,000 words, is about half the length of Major League Baseball’s. It is, however, more than twice as long as FIFA’s Laws of the Game, at about 23,000 words.)

Adds former official and NFLRA boss Scott Green, “It’s taken a life of its own. When I started in the league, it was, when in doubt, it’s incomplete. It wasn’t being analyzed so closely.”

This offseason a six-member NFL committee will yet again reconsider the catch rule. While they’re at it, the league might consider auditing its entire rule book. Rather than an isolated problem, confusion over the catch is a symptom of inherent flaws in the way the rules are written.

* * *

There’s no debating that Pete Morelli’s crew blundered during its Week 12 assignment, Arizona at San Francisco. Among its errors, the crew stalled for nearly five minutes while trying to determine the down after a 49ers penalty. Cardinals coach Bruce Arians later remarked of the officials, “They can’t count to three.”

Blandino, apparently, had had enough. Morelli’s crew, which was scheduled for the Sunday night prime-time game in Week 13, was swiftly reassigned to an afternoon slot with significantly fewer eyeballs. Says Quirk: “I cannot think of another example of a crew being flexed out of a game. I’m not sure what good it accomplished.”

It wasn’t the first time Blandino exercised authority in 2015. The league suspended side judge Rob Vernatchi with pay for his role in the Pittsburgh-San Diego clock error and removed back judge Greg Wilson from a prime-time assignment after the illegal bat fiasco.

• INSIDE THE REPLAY COMMAND CENTER: Peter King goes behind the scenes on an NFL Sunday

To a man, players we spoke with celebrated the idea of punishing officials for missteps. Said Washington defensive lineman Ricky Jean Francois, “The same way they can fine us for a lack of judgment, they need to fine the referees. Let’s make it even. If referees know they can get fined or suspended, the game will go a hell of a lot smoother. They would take the job more seriously, and you wouldn’t have referees way on the other side of field making calls they can't possibly see.”

“To me, these are all unusual PR moves,” Austro, of FootballZebras.com, says. “Ask any official, and they’ll say they go out and officiate the game. If it’s Monday night, it’s Monday night. If it’s Sunday afternoon in a game that airs in two markets only, then it’s that game. The league office, however, has to watch optics. So reassigning Morelli’s crew has the appearance of ‘doing something.’ ”

Many mistakes go unnoticed by the general public, swept away in an avalanche of Sunday NFL content. But the big ones blow up. They get retweeted and GIF’d and broken down to the nth degree by the likes of Pereira, Austin and Mike Carey, former officials who have cornered the new market for officiating expertise in the media. Fox hired Pereira in 2010, a move that other networks and other sports have since replicated.

“Social media has changed everything,” says Pereira. “You’re not ever going to get away with a mistake.”

The rise of the officiating analysts has humanized the refs—and, in the age of HD broadcasts with two dozen cameras and super-slo-mo, further magnified their flaws. It’s not just the masses on Twitter instantly critiquing officials; it’s trained experts with the veneer of authority doing so on broadcasts watched by the NFL’s tens of millions of fans. The presence of former officials on TV has, in a way, institutionalized the process of second-guessing. And the fact that Pereira, Austin and Carey often disagree with their former colleagues on the field or with decisions from the replay headquarters only adds to fans’ confusion and the sense that officiating is inconsistent and flawed.

The expectation of perfection, Pereira says, is a phenomenon as new as it is unattainable. “Social media,” he says, “has changed everything. You’re not ever going to get away with a mistake. And for every mistake that’s made, nobody ever talks about the great call.” Pereira himself tweets prolifically during games.

Quirk thinks critics, as well as the graders in NFL headquarters, need to be realistic about the nature of live-game officiating. “Let’s remember that we are not officiating John Madden’s video game,” he says. “The guys on the field are officiating, at real speed, things that are happening very quickly. The people who are grading the game tapes are looking at it on an HD TV screen, going back and forth in slow motion.”

One former official lamented the inherent stress of having each full-speed call and non-call analyzed and judged against a two-inch thick rule book. “Imagine if your boss sat down and graded every single move you did, minute by minute, in the course of the workday, rather than looking at the total performance,” says the former official, who asked to remain anonymous. “And that’s what determines your bonus.”

By policy, refs are hamstrung. They can’t defend their performance to the press and public save for the occasional explanation to a pool reporter at the conclusion of a game. Coaches and players, for their part, are often fined for speaking out against the officials. Those policies are place, Blandino says, so that he can have honest conversations with clubs without fearing leaks to the media. Instead, Blandino assumes responsibility as point man. He posts weekly videos on the NFL’s website, appears on national radio and even tweets during games. As NFL fans feel closer to than ever to the sport, failure to be transparent spikes skepticism. However, some officiating sources describe Blandino’s public role as “troublesome,” as he and only he can control the narrative.

And now, with the plan to widen New York’s involvement in in-game decisions, the fear is that officials will further question their own judgment and lean on Blandino and others in the league office as a crutch.

* * *

What led to the notion, true or not, that officiating in the NFL has worsened?

A number of former officials point to the 2012 lockout. For one month the football consumer sat front row for a cavalcade of follies, punctuated by the iconic image of two replacement officials standing side by side, one signaling touchdown and the other signaling incomplete pass, all while Seahawks and Packers wrestled on the ground.

They called it the Fail Mary, and Scott Green watched at home in Vienna, Va., waiting for the phone to ring. Goodell later said the game "may have pushed the parties further along" in CBA negotiations.

“This will tell you all you need to know about how little the league thinks of officiating,” Green says. “They literally thought they could go find a bunch of guys who had never refereed in the league and do two training sessions, and they would be capable of officiating NFL football games.”

The CBA that was completed two days after the Fail Mary brought officials back, and drove away many. Retirement benefits were sweetened, according to Green, ushering in a youth movement that some former officials believe laid the groundwork for instability and the inexperience of current crews. There have been 23 new officials since the beginning of 2014, out of a total of 122.

"After you have a new contract and the benefits are bumped, you're going to have a turnover," Green says. "They certainly should have recognized that after the first two years."

The current landscape is not conducive to development. NFL Europe, for all its flaws, was the D-league for officials that the NFL desperately needed. That league tapped rising stars from college and groomed them on the pace and rules of the pros. Though the NFL created an Advanced Development Program three years ago, there is very little applied training. Prospective officials work a few preseason quarters, observe on the sidelines and are thrust into NFL game action.

“You have a requirement that says an official can’t work a Super Bowl for five years, and part of that is because it really takes you five years to get up to the speed of the game,” Pereira says. “Some are doing well and some are struggling, and some are creating difficult situations for the veterans.”

* * *

In March 2010, in his last major act as VP of officiating, Pereira moved the umpire from his traditional spot just behind the linebackers to the offensive backfield. The justification: Umpires were knocked down by players more than 100 times in 2009. Two suffered concussions and three suffered bodily injuries requiring surgery.

The consequence? The umpire may be safer, but officiating crew surrendered the best seat in the house to watch line play. “I never have been a fan of moving the umpire,” says Quirk, who served in that role for part of his 21-year officiating career. “I thought that was one of the bigger mistakes. You took [the umpire] out of the action. If you had an umpire who had good peripheral vision and fast feet, he belonged where he was previously stationed. Right now, it is nearly impossible for anyone to call offensive holding. I personally think it caused more problems that it probably was meant to solve.”

So that’s one idea to improve officiating—move the umpire back to his old spot. There are plenty more.

Pereira still believes the best fix is full-time officials: “I want to see the leaders of every crew work together so that messages can be more consistent,” he says.

A number of players suggested adding an eighth official to the field, a measure implemented by the NCAA and experimented with by the NFL this offseason. Blandino said the goal would be to get eyes on vantages lost when the umpire moved. NCAA penalty data suggest that the eighth official improved the quality of interior line officiating while not significantly raising the number of penalties in a game. But adding another body to each team requires vetting and training 17 more officials in the midst of an era of high turnover.

Amy Trask, former CEO of the Oakland Raiders and current CBS NFL analyst, suggests a tweak to that idea. “Take the extra official idea and add the official to the booth,” she says. “He or she is in constant communication with the referee, and you expand what is reviewable by replay. No behind-the-curtain, Wizard of Oz-type deal. He or she would not be an executive but a teammate of the men and women on the field, one who can review plays from the press box.”

“I don’t care if it works for us or not,” Wright says. “I want it to be right. A small thing can decide a game, so review it.”

Expanding the role of replay could result in longer games, something the NFL and its broadcast partners would like to avoid. Players and coaches, however, are less concerned with that prospect than with getting the call right.

“We ran a play [against the Cowboys] and they called offensive pass interference, and it wasn’t even close,” says Washington’s Gruden. “One thing that would really help the game would be the ability to challenge anything. Look at the pick-six we got against Carolina. They call that back [for illegal contact on the defensive back], and they go down and score and it’s a 14-point swing.

“Let the coaches have one challenge where they can challenge any kind of penalty. I don’t have a problem with the no-calls. It’s the calls that they make that are not actual penalties that drive me up a wall. That’s what makes you feel like it’s personal, when you know it’s not.”

Says Seattle linebacker K.J. Wright, himself the beneficiary of one of the season’s biggest officiating mistakes, “Sometimes they call offensive holding when there is none, and defensive holding when there is none. I don’t care if it works out for us or not; I want it to be right. A small thing can decide a game, so review it.”

* * *

The MMQB agrees.

The disconnect between the broadcast experience and the real game needs to be bridged. Blandino’s instinct to increase communication between league officials watching from the command center in New York and the referee on the field is a good one. We believe that if quarterbacks can operate with offensive coordinators in their ears between plays, officials can have their work checked by Blandino and chief assistant Alberto Riveron, a former referee, from New York.

It’s not acceptable for Blandino to go on television and radio shows on Monday morning and admit to officiating mistakes, as if the mistakes themselves took 12 hours to analyze. We usually know the right answers as they happen, and it’s time to throw the Steratores and Hochulis of the world a lifeline with a permanent policy of increased in-game communication between the league and officials.

If one call a game can be fixed without increasing stoppages, why not do it?

The proposal will allow Blandino or his appointed lieutenant to have a direct line into the ear of officials on the field—to tell them where to spot the football in cases of dispute, or to adjudicate plays that were not under review. The league always says it’s about getting plays right, and if it’s patently obvious that an officiating decision could be corrected, it should be. Also, the eye in New York will potentially cut down on some of the interminable crew conferences on the field. So not only will mistakes presumably decrease, but games might also be shorter.

But let’s go further. As Gruden and Wright argue, the league should allow every play to be challenged—without increasing the number of coaches’ challenges in the game. As much as it would pain the league to adopt an idea originally suggested by Bill Belichick, why make a distinction over which calls are reviewable and which aren’t? If one call per game can be fixed without increasing the number of stoppages, why not do it?

As the screaming headlines over the last 60 years suggest, officiating is never going to be perfect. But by increasing the use of technology that’s already in place and that everyone already sees, the league can help officials and cut down on the public perception that three blind mice are doing most of these NFL games. Surely, it can't hurt.