Mike Ditka’s Kick-Ass Coaching Tree

BY RICH COHEN

It’s one of the great mysteries of modern sports. How is it that Mike Ditka—Iron Mike; the intense, tantrum-throwing player who became the intense, tantrum-throwing coach; the locker room screamer who described his game plan as “last year we were the hit-ees, this year we’ll be the hit-ors;” the man who, when asked by Bears owner George Halas to describe his coaching philosophy said, “What, did ya want me to bulls--- ya? I wanna win;” the man who’s made the phrase “kick ass” into a personal brand, attaching it to a line of fine wines (Ditka’s Kick Ass Merlot), a menu item at his steakhouse (Ditka’s Kick Ass Paddle Steak) and one of his two autobiographies (In Life, First You Kick Ass); who, in explaining why he was so confident of victory, said, “they’re the Smiths, we’re the Grabowskis;” who once threw his gum into the hair of a sideline heckler; who, at key emotional moments, has misquoted Robert Frost and Frank Sinatra; who offered to kick his defensive coordinator’s ass during halftime of a Monday Night Football game—how did this man become the trunk of one of the mightiest coaching trees in pro football? Six of Ditka’s former players have served as head coaches in the NFL. Others have worked in front offices, as assistants and scouts, or coached in college, not to mention Ditka’s great safety, Gary Fencik, who steered his daughter’s little league team to a championship. You might expect that from one of the old philosophical types: Sid Gillman or Bill Walsh. But Ditka?

It’s a question that haunts me—as a Chicagoan, as a Bears fan, as a student of human nature. How is it that one of the most brutal, monosyllabic coaches of our era fostered such a remarkable legacy?

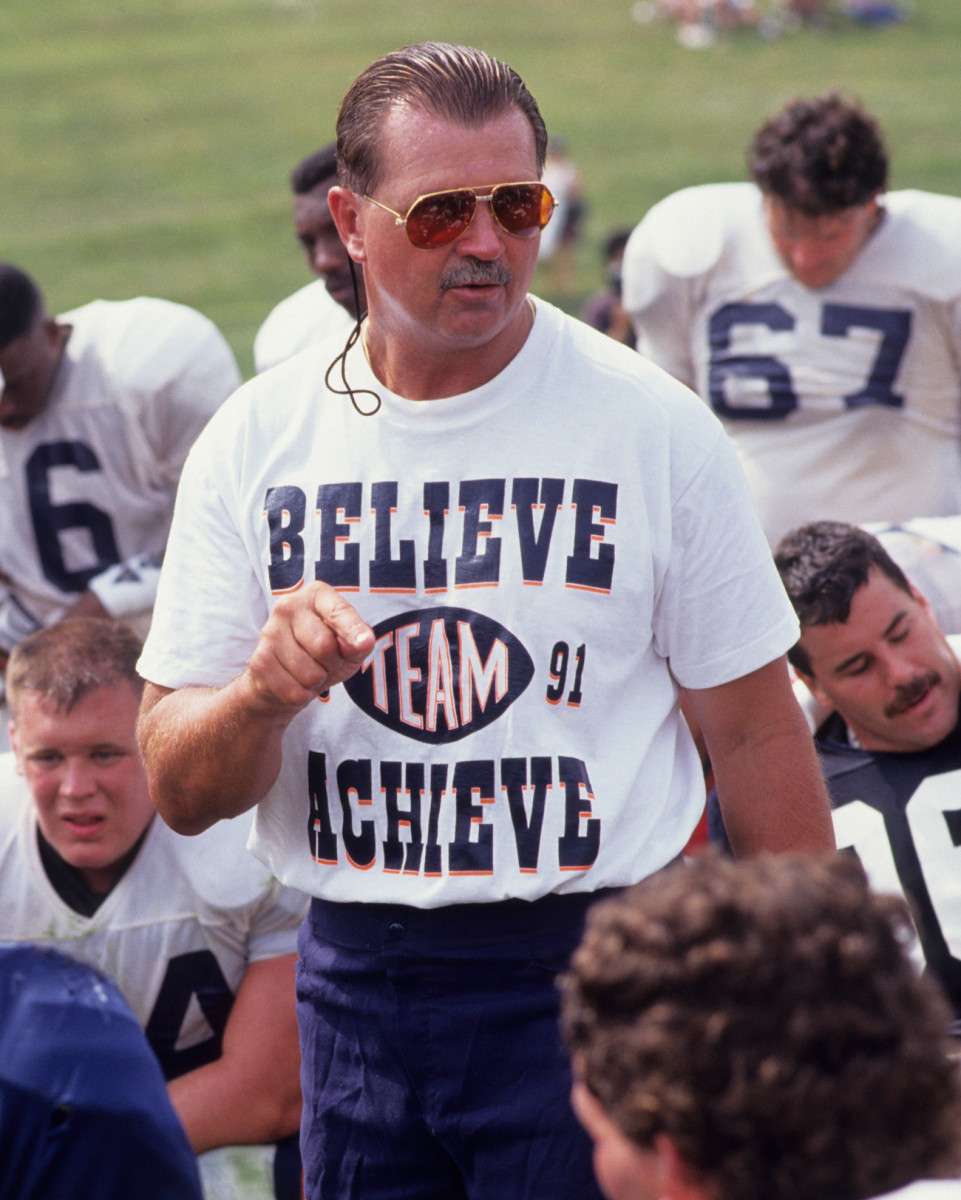

If the Ditka Coaching Tree were organic rather than conceptual, it’d be a crab apple tree, all twisted shoots reaching for the sun. This year’s prime example is Ron Rivera, a Bears linebacker from 1984 through ’92, after which he went first into insurance, then into coaching, serving as an assistant or coordinator in Philly, Chicago and San Diego. In 2011 he got the top job in Carolina, where he runs a smash-mouth defense that looks like a bastard son of the Bears’ old 46. “Ditka was a hard-ass,” says Rivera, whose Panthers stand at 14-0, with an excellent chance to finish the regular season undefeated and win home-field throughout the playoffs. “He pushed, pushed, pushed. It took me a lot of time to understand why he demanded so much, why he was so upset when we didn’t do certain things right. He played the game and believed that if he could do it, you could do it. His standard was very high because, quite honestly, the guy’s a Hall-of-Famer.”

Then there’s Jeff Fisher, a coach’s coach who led the Oilers and Titans to 142 wins and six postseasons and has coached the Rams for the past four years. When I asked Fisher if he’d been influenced by Ditka, he laughed. “If you got a chance to watch Ditka work in the early ’80s, you never forgot it,” he said. “We all had an appreciation for his hard work. He was all about survival.”

Fisher—who under Ditka played safety alongside Doug Plank, the Human Missile, the big-hitting D-back whose jersey number gave the Bears defense that name, 46—injured out in 1985, then went on to work as an assistant in Philadelphia, Los Angeles and San Francisco before landing his first head coaching job in Houston in ’94. Fisher is the only tree branch to surpass the trunk in wins: 168 to Ditka’s 121. He’s got the Ditka walk, the hard gaze, the moustache. And the D. “Jeff runs a very aggressive, creative defense,” says Plank. “Overload the line, send people at the quarterback from every angle, attack, knock that QB down 10 times.”

“I was a Chicago kid,” says Sean Payton. “I knew him as a fan before I found myself in pads being yelled at by him. I was scared to death.”

Altogether, upwards of 35 men who played under Ditka (either with the Bears or, later, with the Saints), went on to coach professional, college or high school football, some as assistants, some as head coaches. Among them, notably: Leslie Frazier, a Bears cornerback who coached the Vikings from 2010 to ’13; Mike Singletary, a Hall of Fame linebacker who coached the 49ers for parts of three seasons; Jim Harbaugh, a onetime Bears quarterback who replaced Singletary in San Francisco and took the Niners to the Super Bowl before moving on to his alma mater, Michigan; Ken Margerum, a Bears receiver who coached the position at Stanford and San Jose State; Brian Cabral, who captained the Bears’ special teams before he coached at Colorado. And don’t forget Rex and Rob Ryan, sons of Bears defensive coordinator, Buddy Ryan, who were ball boys when Ditka was chasing down assistant trainers—I’m looking at you, Brian McCaskey—who’d used his hair brush and cologne.

There’s Sean Payton, Super Bowl-winning coach of the Saints—but “a lot of people are going to give you s--- if you include Payton,” says Fencik, because Payton played quarterback for Ditka’s Spare Bears, the replacement squad put together during the 1987 strike. “Payton was a scab.”

“I don’t blame Sean for wanting to play in the NFL,” says Dan Hampton, the Hall of Fame defensive tackle known as Danimal. “Everybody calls them the scabs; hey, they were just looking for an opportunity. I understand it. But Payton played, what, three games for Coach? Ships passing in the night.”

“It was just a month,” Payton concedes, “but Ditka left a big impression. I was a Chicago kid; I knew him as a fan before I found myself in pads being yelled at by him. He’s a big guy. And you knew what kind of player he was—ferocious. And he had that mustache that’d freeze, and was it water? Or was it spit? I was scared to death. But what stayed with me was his intensity. My God, did this guy want to win!”

There was something inspiring about playing for Ditka, Payton goes on to explain. It seemed to connect you to the origin of the game, the dawn of professional football, when the sport was a scrum of factory workers beating the hell out of one another between shift whistles. Such men understood the truth: The ball is merely pretext, a dingus, a McGuffin. Hitting and getting hit, that’s the point.

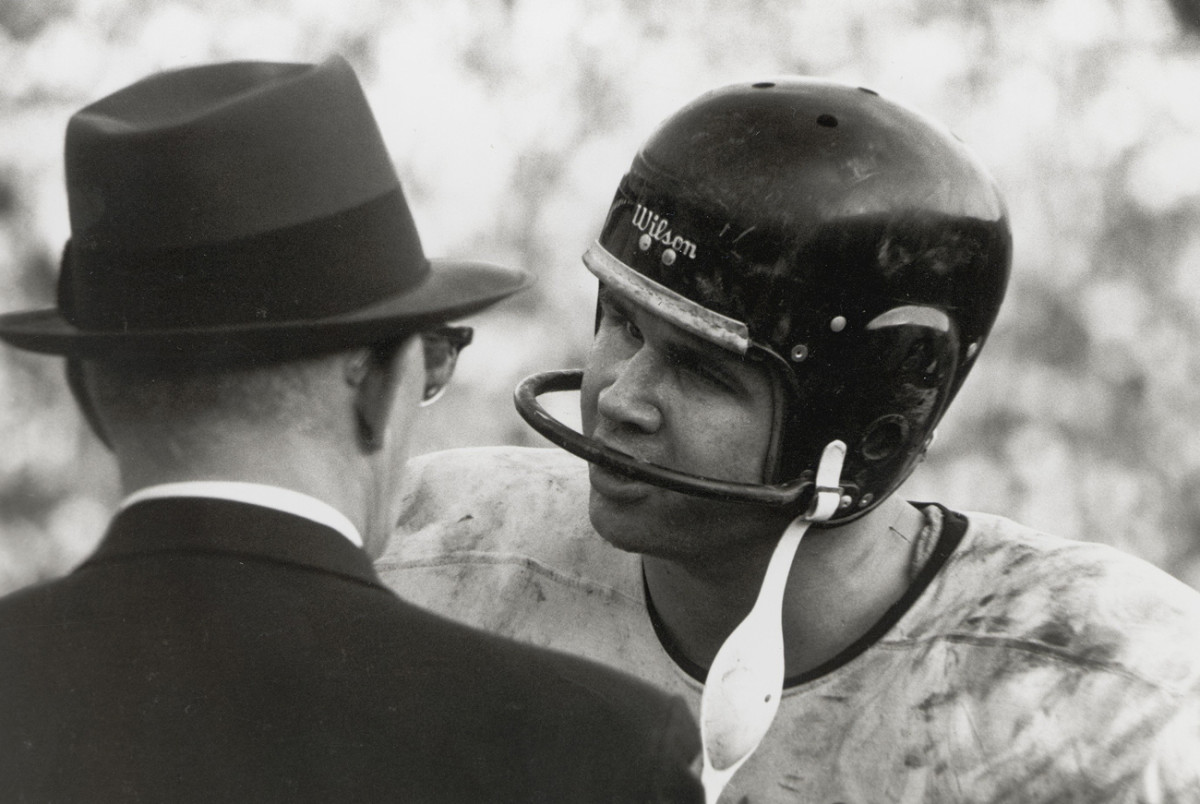

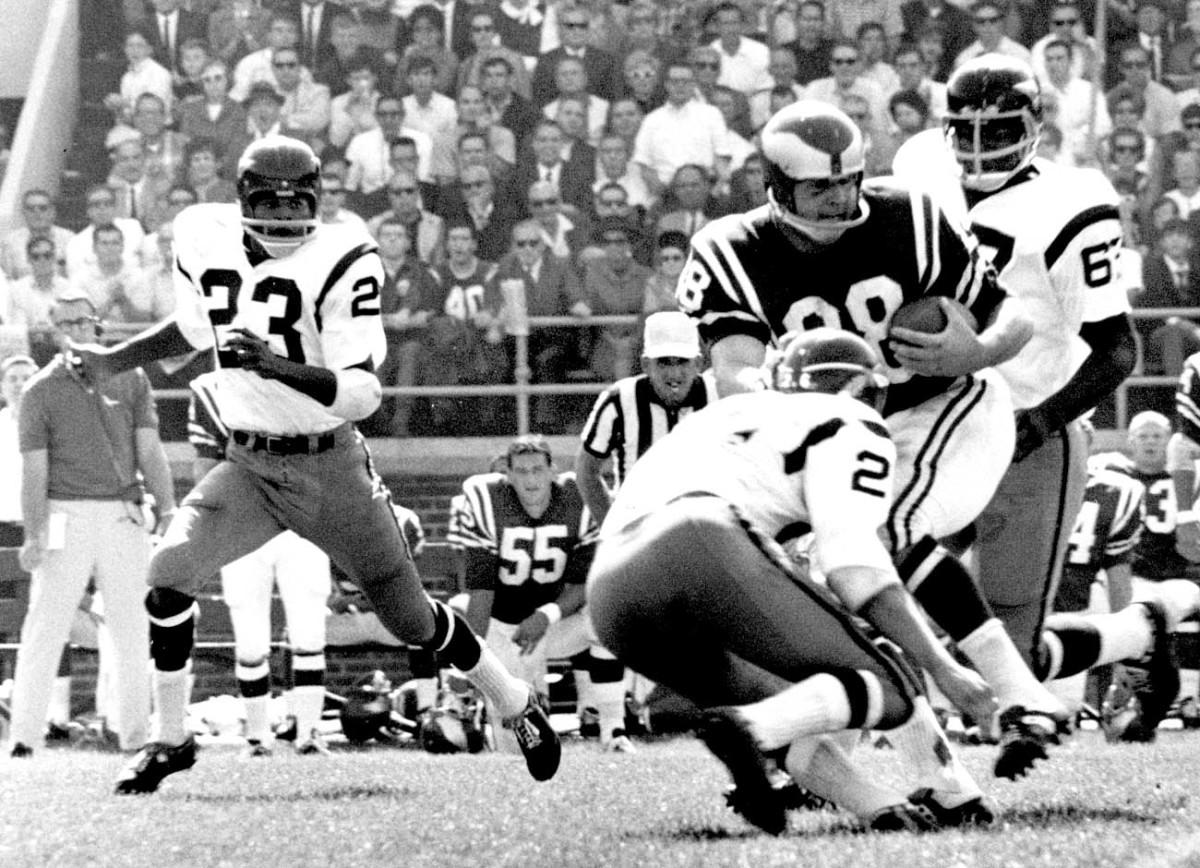

Ditka learned that from his own great coach, George Halas, who’d actually played in those early games, for the Hammond Pros, a gang of malcontents who took on all comers. Halas, a defensive end who once stripped a ball from Jim Thorpe and ran 90 yards for a touchdown, built a team for Staley Starch in Decatur, Ill., in 1920, then moved that team in ’21 to Chicago, where they became the Bears. Along the way he founded the NFL with a handful of other owners. In Ditka, an All-America from Pitt, Halas, recruiter of Red Grange and Bronko Nagurski, saw yet another paradigm-shifting weapon. Young Iron Mike was an oddity: as big as a lineman, with flanker-soft hands. If he could get downfield and catch a pass in the secondary—he greatly outweighed most defensive backs of the time—they’d never get him on the ground. Check the footage: Ditka plodding across muddy fields, carrying three our four gang tacklers on his back. He caught 56 passes his first season in Chicago. In this way, Halas turned Ditka into the first modern tight end, godfather of Bavaro and Gronkowski. “If I had to pinpoint one thing, I would say the legendary George Halas,” Jim Harbaugh once said in trying to explain the tree. “We all came to know the legendary George Halas through the qualities of Mike Ditka.”

“My rookie year, after three or four games, Coach Halas wanted to talk to the team,” says Fisher. “I’d returned a punt for a touchdown, and I met Coach Halas in the building and introduced myself. He recognized me. I was blown away by the fact that this legend knew who I was. In the meeting, he grabbed a ball with his quivering hands and put a finger over the point of the ball and said to Walter Payton, because Walter had fumbled, ‘This is how you hold a football.’ Then he went off on what we thought was a tangent—World War II, Lou Gehrig—and you just thought, Ugh, he’s never gonna. . . . But he circled right back, tied it all together. It was really cool.”

Halas taught Ditka to compete. Landry taught Ditka to lead.

Ditka and Halas were like father and son. Like father and son, they fought. Halas warned Ditka about his carousing; Ditka mocked his mentor for his stinginess—“The old throws around nickels like they’re manhole covers.” Ditka was an All-Pro in Chicago and led the team to an NFL championship in 1963, but Halas traded him away for almost nothing in 1967. (Talking to a reporter, Ditka had cracked wise about Halas’s Czech heritage—“I called him a cheap Bohemian,” Ditka wrote—a red line for the old man, who promptly banished his tight end.) Ditka played two forgettable seasons for the Eagles and then ended up in Dallas, where he connected with the other great coach in his life, Tom Landry.

Whereas Halas was a screamer and sideline stalker, a genius of profanity who could deliver a three-word sentence in which two of the words were curses, Landry was a taciturn, stone-faced born-again in sports jacket and fedora. He’d been a bomber pilot, shot down in World War II. He’d been a serviceable defensive back. He was an assistant on the world-champion 1956 Giants alongside Vince Lombardi and invented the 4-3 defense. Landry had an uplifting effect on everyone lucky enough to enter his orbit.

To understand Ditka’s tree, you must therefore understand his own place among these other great oaks, Halas and Landry. Halas taught Ditka to compete. But Landry taught Ditka to lead. “Ditka learned professionalism from Landry,” retired Cowboys quarterback Danny White once told me. “He learned that as a coach you have to control your passions. I think those years in Dallas made Ditka a coach. It calmed him down.” What about those who say, How can that be? Ditka was the opposite of calm in Chicago. White: “Try to imagine Ditka without the influence of Landry. He would have been a raving lunatic.”

When Ditka retired as a player, in 1972, Landry tapped him immediately to coach the Cowboys’ special teams. He was not an obvious candidate. Coaches of that era tended to be contemplative, cool. Ditka was a live wire, a muscle car with its engine showing. When Halas called him home to be coach of the Bears in 1982, many Chicagoans recoiled. That madman?

“I had immediate respect for the choice because I’d played against his special teams,” says Plank. “The special teams coach is the most like a head coach. He’s got guys who do everything: runners, hitters, kickers, punters, offense, defense. . . It’s a team within a team. You can tell a lot about a coach by how that unit handles itself. Ditka’s guys were always tough. And when they played, Mike stood on the sidelines screaming like he wanted to run out on the field and choke someone.”

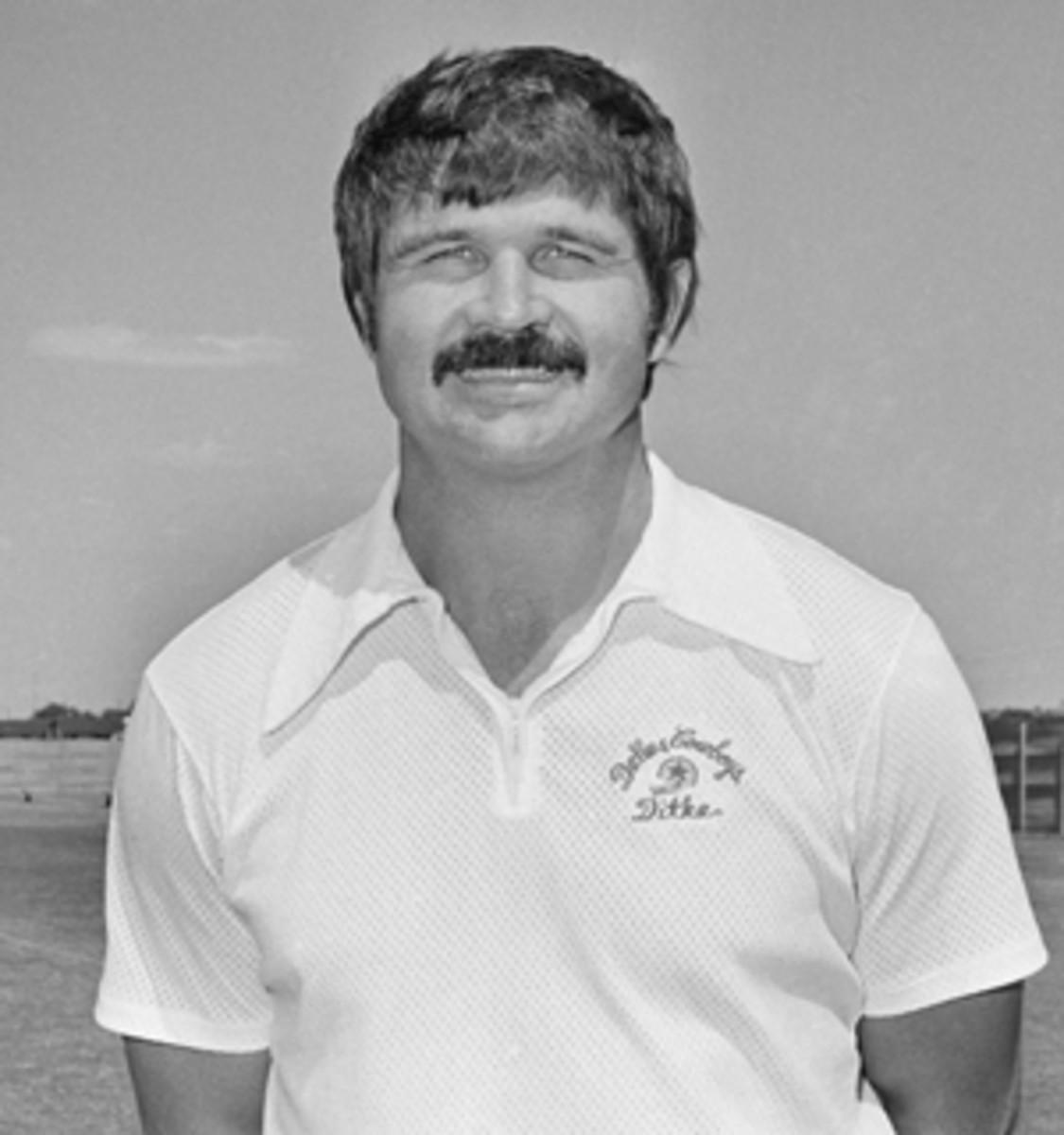

Ditka returned to Chicago in the way of the prodigal. The setup was Biblical. He’d won a championship with the old man; now he’d win a championship for the old man. The once-crew-cut tight end, meanwhile, had turned rank with the 1970s: polyester, perm, painfully short shorts. “The first time I remember seeing him was at his contract signing,” says Hampton. “I think he was wearing a suit and tie and had that curly hair. He was sitting next to Halas, and we were all like, Let’s see how long this lasts.”

“My first impression, really, it’s funny,” Rivera says of Ditka. “He just reminded me of a bear.”

Style. That’s what Ditka brought to Chicago. Maybe that, more than his playbook or tricks, explains his influence. Style is the overlooked element in history. We tend to study words, dates and events—that is, the lyrics. Style is the music, what lingers when all the other details have faded. The way Ditka dressed, carried himself, how much he wanted and cared; the way he conducted press conferences—it became a kind of theater in Chicago, as if he were coaching not just the players but the fans. Fans who’d grown downcast, defeated. “You first meet him and everything is rosy and glowing. Then you start practicing and realize, Holy s---! He turned it up a bit!” says Rivera. “My first impression, really, it’s funny: He just reminded me of a bear.”

Ditka began cutting players, veterans and stars, anyone not going all out. He was changing the culture, which had become rotten—three winning seasons in his 15 years away. Remorseless determination is what all those future coaches took away from those first weeks with Ditka. “The only thing that mattered was whether you bought into Mike’s way of doing things,” says Frazier. “There were guys who I thought were secure in their jobs, and suddenly they’re gone. I learned from that. Name recognition means nothing. It was gonna be the best guys on the field. Every decision was based on winning.”

By 1984, the Bears were one of the best teams in the NFL. The defense, perhaps the most devastating in league history, was stocked with Pro Bowlers and future Hall of Famers. The offense was carried by Walter Payton and Jim McMahon. Altogether it felt like an era but turned out to be an interlude. It peaked in ’85, when the Bears made their Super Bowl run. That season was a crucial fertilizer for Ditka’s tree. It was not only the coach who drove players into management—it was the inebriation of winning, especially this kind of winning, circus-like and unreal, McMahon changing Ditka’s plays as Ditka blew up on the sideline, William “the Refrigerator” Perry dancing in the end zone of some poor sacked city as the Bears did the Super Bowl Shuffle.

* * *

There’s more to growing that tree, of course. If I was being complete and honest, I’d draw your attention, for starters, to Buddy Ryan, the defensive coordinator who, having been guaranteed his job by Halas, could not be fired by Ditka. Thus he became a kind of second head coach. In 1985 a not uncommon site would be Ryan greeting his boss, “F--- off, Ditka; I run the defense.” The result was a rivalry that drove the Bears to greatness. “Buddy definitely made it, The defense is gonna win this game, no matter what the offense does,” says Frazier. “He created an environment where the defense had to outdo the offense because our offense, in his mind, wasn’t up to snuff. Other than Walter. Buddy would always say: ‘We’ve got one player on offense, and that’s Walter Payton.’ ” The defense became a kind of cult, with an us-against-the-world outlook. It’s no accident that most of the coaches on Ditka’s tree come from that side of the ball and had been locked up with Buddy, whose clannish approach thrived on true believers.

There were also those stunning drafts of the early 1980s, overseen first by general manager Jim Finks, then by Bill Tobin and Jerry Vainisi. In ’83, the Bears snagged seven eventual starters, four future Pro Bowlers and one Hall of Famer-to-be, defensive end Richard Dent. Tobin once told me that the key was in drafting for character. In those years the Bears might pass on the biggest or strongest or fastest prospect, instead going for a football guy, a player who understood intangibles, had that feel and love for the game that Halas called “the old zipperoo.” Enter McMahon, who was short for a quarterback, half-blind in one eye and of questionable arm strength and turpitude. He drank beer and chewed tobacco, slept on a water bed and mooned the news chopper, but he could find the end zone. That is, the Bears drafted the kind of people who were more likely to become coaches—passionate savants. “It’s a saying we had,” Tobin explained: “When in doubt, bet on character. That’s why we ended up with the Leslie Fraziers and Jeff Fishers and Ron Riveras and Mike Singletarys. When your best players are also your best people, you’ve got a lot going for you.”

Sean Payton offers an even simpler explanation for the tree: Ditka was a coach for 14 seasons, an eon in football time. (After a decade, an NFL coach is older than any man in the world.) “It’s simple math,” Payton explains. “If you have staying power, if you’re in the game long enough and work with enough players, coaches are going to spin off your system.”

Ditka had no great philosophy. His vision was ass-kicking human will.

And yet, it’s still surprising. Because you expect Ditka to deter would-bes, scare people away from his path. Because he made everything look so hard and mean and coached himself into a heart attack. Because he flipped reporters the bird and told off hecklers and chewed gum with such fury that it made you feel sorry for the gum. Because he was arrested for drunk driving after one of his team’s great victories and stood by his vehicle in cuffs as players roared past on the highway, honking.

Most famous coaching trees have at their base a maestro with a vision, an intellectual take on the game that can be perfected and passed on to acolytes who adjust and carry it forward in the way of a philosophical theory. Sid Gillman, who pioneered the downfield passing attack in San Diego—his disciples included Al Davis, Chuck Noll, Dick Vermeil and Don Coryell. Bill Walsh, who pioneered the West Coast offense in Cincinnati and San Francisco—his disciples included Mike Holmgren, Sam Wyche, Jim Fassell and Dennis Green. But Ditka had no great philosophy. His vision was Nietzschean. Ass-kicking, human will. Smiths vs. Grabowskis. Hit-ors vs. hit-ees. In the half-light, the head man, leading the team in prayer, says, “Dear Lord, give us the strength to kick their ass.”

“Here’s the deal,” says Hampton. “Bill Walsh was a great coach, in the Hall of Fame. He comes from the school of, Get it where they ain’t. Ditka comes from the school of, I’ve got a bigger hammer and I’m gonna hit you anywhere I want. Two different ways.”

In other words, it was not Ditka’s ideas that proved mesmerizing. It was the profile, the countenance, the moustache. Like they ask the followers of Jesus: Do you worship the message, or the life? And, as Ditka had no message, there was only the life. “Ditka morphed from a nutty, animated assistant to a dignified figure,” Hampton goes on. “By 1987 he’d become The Man in football. I could tell that he’d made a mark not only as a coach, but as a model for a lot of players. It was weird. In the Walsh or Bill Parcells tree, it’s all assistants [who went on to top jobs]. But every one of the guys on Ditka’s tree was a player. I think it comes down to what Ditka stood for, the attraction of his life. Who wouldn’t want to be Mike Ditka? He was a rock star! He was dashing! In ’86, every man wanted to be Ditka. He was like the world’s most interesting man. A lot of players wanted to live that same kind of life.”

That, of course, could not last. Ditka ran too hot for the long haul. He fell afoul of Mike McCaskey, who’d taken over when Halas died in October 1983. He fell afoul of some players, some fans. The era had changed on him. It was no longer O.K. to humiliate a quarterback on national TV or work the boys to death. “I don’t think you could still coach that way,” says Fisher. “The players are completely different. Back then, in the third week of training camp, after your 20 consecutive two-a-day practices, in the afternoon, when practice was over and it was 90 degrees, Mike said, ‘Line up on the goal line, we’re gonna run 10 hundreds.’ Today’s player would stand there and look at you and ask, What?”

* * *

Ditka comes from an older America, a nation rusted over, gone. He’s turned into an oddity, a relic. He cried at his last Bears press conference, then sought solace in the lyrics of Paul Anka, the last refuge of the self-pitying man. He took one more coaching job: New Orleans. The Saints. Can you imagine a sillier culture clash? Iron Mike in the City that Care Forget? He lasted three seasons, all bad, then settled into the life he still lives. Ditka being Ditka. Ditka prized for Ditka-ness. He owns resorts, sells sausage and wine, shows up every Sunday on ESPN, where he remains mountainous, craggly, grand. He runs an eponymous steakhouse on Chestnut in Chicago, which is where I met him a few months ago to discuss the tree. He was in a booth in front, drinking iced tea. He wore a gray jogging suit and looked as satisfied as a retired mob boss on Mulberry Street.

“We’ve met before,” I said.

He grunted. “You think I don’t remember, do you? You think I’ve been hit in the head so many times I can’t remember anything.”

He paused, laughed, then said, “Well, you’re right. I don’t remember.”

The walls at Ditka’s are covered with photos: Ditka as a player and a coach; Grange; Gale Sayers; Singletary. The place is like an Egyptian tomb, the crypt where the monarch will be buried with his dog, his servants, his trinkets and his memories.

I asked Ditka about the tree. Did it surprise him? Was he proud?

“Everything surprises me,” he said. “Take a guy like Les Frazier; he’d be the last guy in the world you’d think would be a head coach. Ron Rivera, yeah. Mike Singletary, yeah. Jim Harbaugh, yeah. Fisher, yeah. But Les Frazier was the quietest guy in the world. Singletary was a coach on the field. I could say the same about Hampton. I take pride in every one of those guys, ones that aren’t coaching, too. I remember everybody from that team, even the ball boys. It was a good time in America.

“You’ve gotta get old to get smart. I’m smart now; I really am.”

“The game has changed in so many ways. In my day, you negotiated face-to-face with the old man, Mr. Halas. My first contract was $12,000 a year with a $6,000 signing bonus. That’s $18,000. I’m not brilliant, but I know that. So the next year I went in and he said, ‘I’m gonna give you a raise. I’m gonna pay you $14,000.’ I said, ‘That’s not a raise! I made 18 last year.’ I said I wouldn’t sign for a penny less than 18. As soon as I said that, he drew out the contract and I signed it. He was shrewd. But what’s the difference? I wanted to play football; he knew that. That’s what I was, a football player.”

“Do you think you could still coach today?”

“With the mental attitude I have now, yeah,” he said, “Otherwise, you burn yourself out, drive yourself, push yourself. It’s crazy. Wisdom is wasted on the young. You’ve gotta get old to get smart. I’m smart now; I really am.”

He sighed, smiled, stood—slowly, with effort. “Football’s been my whole life,” he said. “I love the game, respect it. But if you play long enough you will get some type of injury. I’ve had four hip replacements. Shoulders too. Had a foot done. But I’m O.K. I work out every day. If they’re gonna push me into a hole in the ground, at least I’m gonna go on my terms. I just came back from Florida; I played 18 holes with some people and played 18 more by myself. I don’t give a damn. I’m gonna do all I can before they get me.”

He wandered around, pointing out and explaining pictures. We ended up in front of a shot taken soon after he’d been hired to coach the Bears: Ditka in a golf cart beside Halas, who looked as old as Methuselah.

“It all starts with Halas,” Ditka said. “Halas was the beginning of the NFL. Him bringing me back to run the Bears was the gift of my life. Why did so many guys who played here go on to coach? Because of that man and this town. There’s nothing like Chicago Bears football. If you experience it when you’re young, you’ll never want to quit the game.”