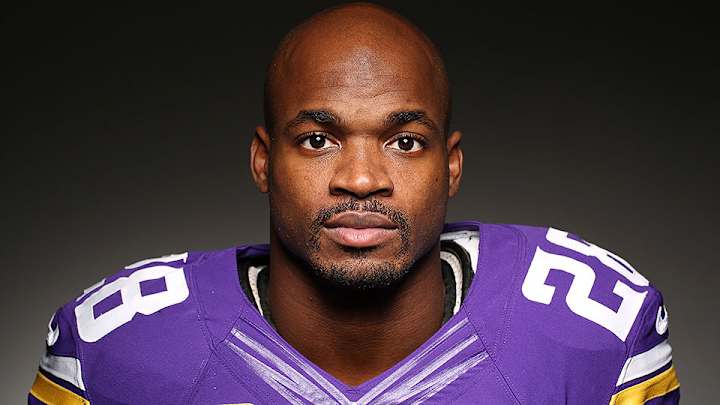

Adrian Peterson sorts out his feelings on fatherhood, forgiveness, loss

This story appears in the Jan. 4, 2016, issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

One morning deep into his ninth NFL season, Adrian Peterson exits his house in suburban Minneapolis and climbs into an idling SUV. His home is between holidays, with pumpkins stationed at the door and Christmas lights hung from the gutters. A gold pendant, two hands clasped in prayer, dangles from his neck.

It’s early December, Week 13, and the Vikings sit atop the NFC North standings. Peterson, the NFL’s rushing leader with five games to play, is once again their catalyst—though that seemed improbable last spring, when he was suspended by the NFL, turning 30, considering retirement and hoping for a trade out of Minnesota. The black Escalade pulls onto streets lined with snow. The anger and uncertainty Peterson felt last season are shelved for now, if not forgotten.

“So,” he asks a Vikings representative traveling with him, “what can you tell me about the little guy?”

The little guy is a four-year-old boy named Skyler Elfering, and he has neuroblastoma, a cancer that develops in immature nerve cells. Large tumors have invaded Skyler’s chest and abdomen; six rounds of chemo-therapy, a bone-marrow transplant, and weeks of radiation treatments have been ineffective in treating them. Peterson, who learned of Skyler’s situation through the Vikings, is headed to his home for a visit.

Skyler’s father, Shane, is wearing a Vikings T-shirt and waiting in the driveway. Before Peterson can express support, Shane shakes his hand and says, “I’m sorry to hear about your son.”

Peterson nods, thanks him and pauses. What can he say? That two years earlier a son he never knew was murdered? That the man who did it had been sentenced to life in prison without parole? Or maybe Shane meant something else entirely.

Peterson says nothing and steps inside. Skyler rests on a recliner, wearing Peterson’s jersey, the familiar number 28. Peterson affixes a Vikings bracelet that blinks purple on Skyler’s wrist. “My son, he’s about your age,” Peterson says.

The conversation meanders, and Shane delivers one-liners to lighten the somber mood: “We were going to get you some stickum for those fumbles” and “He wants you to beat the Packers for once.” Skyler flexes for Peterson, who flexes back, signs a helmet and poses for pictures. Peterson encourages Skyler to eat, to play outside, to keep fighting. “This is the world’s best fighter right here,” Shane says, motioning toward Peterson.

On the Numbers: The 1,000-yard RB shortage and Newton’s unique year

Peterson turns to Skyler, their faces inches apart. He says, “Through my life, there are things I’ve been through. Injuries, losing loved ones, having something taken away from you. I’ve been through all of that.”

Skyler stares into Peterson’s eyes. Later, the boy will insist on going outside to throw the football. He will ask to eat for the first time in days. Peterson will return home to his wife, Ashley, and their two sons. He will spend that evening looking at the older one, Adrian Jr., a four-year-old like Skyler, and thinking about fatherhood and children and the last 18 months of his life.

What he won’t do is scroll through his Twitter mentions. Two days later someone posts, “You shouldn’t even be in the league child abuser.”

Oct. 29: Eden Prairie, Minn.

This is when I knew Roger Goodell was blind to the fact of what I was going through. I sat down with him. He asked me, 'What is a whuppin'?'

“Roger Goodell, man, I don’t know. . . . This is when I knew he was blind to the fact of what I was going through. I sat down with him. He asked me, ‘What is a whuppin’? . . . It was one of the first questions. . . . It kind of showed me we were on a totally different level. It’s just the way of life. For instance, in Texas, we know what whuppin’s are. Down there, if it snows, people are going to go crazy. They’re going to close schools. They’re going to shut it down. Here, you’re used to that. It was just a tough situation, because of misperception. . . . I get it. I get why. But you still shouldn’t pass judgment on people when you don’t know.”

On Sept. 11, 2014, a grand jury in Montgomery County, Texas, indicted Peterson on child-abuse charges. But it wasn’t until last April 7 that the running back and the NFL commissioner met to discuss the case. “I tried to schedule meetings with him, phone calls, and for whatever reason it didn’t happen,” Peterson says.

Peterson described that April meeting at league headquarters in New York City during a series of five exclusive conversations with SI during the 2015 season. (A person with knowledge of Peterson’s interactions with the league office disputes that he tried to schedule meetings with Goodell. The same person says the commissioner asked Peterson what a whuppin’ was because he wanted to better understand Peterson’s version of what happened.) At the outset Peterson established a ground rule for the SI interviews: He did not want to linger on the events of 2014. Yet he repeatedly returned to them, his dark-brown eyes widening with intensity.

The case against him was laid out in a police report detailing an incident in May 2014: Peterson had swatted his then four-year-old son with a thin branch called a switch, leaving the child with bruises, welts and cuts on his legs, back, arms, buttocks and scrotum. (The boy, whose name has not been made public, lives in Minnesota with his mother. Peterson has had seven children with multiple women; he says they all visit him each off-season, and he speaks with them throughout the year on FaceTime and Skype.) Police charged Peterson with reckless or negligent injury to a child, a felony that can carry two years in prison, and he testified before a grand jury in August 2014. On Sept. 4 the grand jury decided not to indict Peterson, and three days later he gained 75 yards on 21 carries in the Vikings’ season-opening victory over the Rams. On Sept. 11 the grand jury reversed course and indicted Peterson. Four days after that he released a statement that read, in part, “I am not a perfect parent, but I am, without a doubt, not a child abuser.”

More than a year later Peterson maintains his innocence. He says he never meant to harm his child. He says he apologized—to the boy, to the Vikings and to the public—and took responsibility. He says he understands why people who saw the police-report photos of the child’s injuries, which were illegally leaked shortly after the indictment, may never forgive him. But he does not believe his actions constituted abuse, and he doesn’t particularly care when others—doctors, social workers, parents across the country—think they do.

I know in my heart there’s not many fathers better than me. I’m that father that the kids run to. I’m the father they want to wrestle and play with.

The public reaction to Peterson’s case was swift and harsh. Mark Dayton, the governor of Minnesota, called his actions a “public embarrassment.” Nike and Castrol suspended their sponsorship deals. Cris Carter, a Hall of Fame receiver and former Viking, delivered an impassioned speech on ESPN attacking the culture of discipline in the South. He said his mother, a woman who raised seven children on her own, was wrong for striking him.

On Sept. 17, with the league’s handling of off-field misbehavior under intense scrutiny following the release of the Ray Rice domestic-violence video, the Vikings placed Peterson on the commissioner’s exempt list, meaning he was banned from all team activities—with pay—until his case was resolved. Peterson told himself to let it all go, to pray. But it still bothers him. “I know in my heart there’s not many fathers better than me,” he says. “I’m that father that the kids run to. I’m the father they want to wrestle and play with.”

He stops. Sighs. “Cris Carter, he had so much to say,” Peterson says. “In that stage, if I would have seen Cris Carter, I probably would have slapped the taste out of his mouth.” Another pause, as if Peterson realizes how this sounds. “Because that was the mind frame I was in,” he says. “I wouldn’t have done it. But I wanted to.” (Carter and Dayton did not respond to interview requests.)

The 2014 season went on without Peterson. On Nov. 4 he pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor reckless assault charge; he was ordered to undergo counseling, pay a $4,000 fine and perform 80 hours of community service. He hoped the plea agreement would speed up his return to football. Instead, the NFL suspended him for the rest of the year without pay. Goodell, whose authority and public perception were still shaky because of his mishandling of the Rice case, wrote that Peterson showed “no meaningful remorse.” Peterson was perplexed. He had apologized. He had said he never meant to harm his son. He had promised to “reevaluate” his disciplinary methods. What more did he have to do?

The league cleared Peterson to return to the Vikings last April. As this season unfolded, he grappled with ideas of understanding and forgiveness. He ran for 1,485 yards, won his third rushing title, moved to 17th on the all-time NFL rushing-yardage list—and heard his case come up less and less. People who he says “stomped on me last year” now patted him on the back, celebrating his success.

The season he had speaks to Peterson’s resiliency and football prowess, but not to his personal growth—and he’s careful not to confuse them. Peterson doesn’t want his on-field performance to factor in to his public forgiveness. He wants people to understand how he views what happened, the cultural divide that in his eyes led to his scorning. But, with a shrug, he agrees with Ashley, who says, “I feel like if he wasn’t having such a great season, the reaction wouldn’t be as positive.”

On Nov. 22 the Vikings lost at home to the Packers, with Goodell in the TCF Bank Stadium stands. Earlier that day the commissioner told reporters that Peterson was “a wonderful young man” who had taken his incident “seriously and said, ‘I want to do better.’”

The two men did not speak.

Nov. 19: Eden Prairie

Because I was immature, I missed out on being able to see my son call me Dad. That’s something that I have to live with for the rest of my life. . . . My first time seeing him, he was on his deathbed.

“Here I am, young, I’m not seeking to find out if this child is mine. [But] we finally were able to get in contact with each other and get a test done to see if I was the father. And I found out he was mine. . . . Because I was immature, I missed out on being able to see my son call me Dad. That’s something that I have to live with for the rest of my life. . . . My first time seeing him, he was on his deathbed. He was sitting there, with tubes in his mouth. It was unexplainable, the feeling that I had. I really had to stay prayed up. But, you know, it helps me with moving forward and making sure that I always keep my kids near. It’s a reminder that, hey, tomorrow’s not promised to anyone. So cherish the time you have with your family, your kids. Because you never know.”

Much of his life has been defined by loss, but nothing prepared Peterson for the death of Tyrese Ruffin on Oct. 11, 2013. An autopsy showed that Ruffin suffered four blows to the head that caused his brain to bleed. Three weeks earlier, Peterson had discovered through a DNA test that Ruffin was his son. He saw the two-year-old boy for the first time the day before he died.

In some ways, Peterson blamed himself. Why hadn’t he taken the paternity test earlier? What if the boy had been with Peterson the weekend he was assaulted, instead of in Sioux Falls, S.D., with his mother, Ashley Doohen, and her boyfriend, Joseph Patterson, who was convicted of delivering the fatal blows and is serving a life sentence for second-degree murder? “We finally got justice,” Peterson says.

His son’s death was yet another loss in a life filled with hardship. That theme started early, when Peterson’s brother Brian was killed by a drunk driver when the family lived in Dallas. Peterson stood five feet away from the collision. He saw the car send nine-year-old Brian flying, and he ran over, fell to his knees and placed Brian’s head in his hands. He was there, saying goodbye, when Brian went off life support. Adrian was seven.

Peterson’s mother, Bonita Jackson, cried every day for a year after that. He did his best to comfort her. He also decided that whatever negatives he faced—death, injury, snubs, doubts, even his own failings—would fuel him. “That shaped me to deal with things I confronted in my life,” Peterson says. “Some things I couldn’t avoid. Some things I could have. But there’s not much that shakes or rattles me. There’s not much I can’t handle. People take that as arrogance, like I don’t care.”

Then, gently, he says, “It’s not that.”

Peterson’s father, Nelson, was a star basketball player at Idaho State who signed a contract with a pro team in Puerto Rico, before a gun his brother was cleaning went off and the bullet shot through Nelson’s left leg. He almost lost the leg to a staph infection. He did lose the contract.

So he channeled his focus into Adrian, who was two at the time. Nelson used soda cans in place of cones for footwork drills and instructed older cousins to smash into Adrian at full speed from five feet away, then eight feet, then 10. He wanted Adrian to know what contact felt like, then trained him to deliver blows rather than absorb them.

Nelson had been working at Walmart as a lift driver, earning $8 an hour, when he decided to start selling crack. When he was arrested for laundering $200,000 in drug money, Adrian was 13.

The father spoke to his son almost every day from prison. He wrote Adrian twice a week and advised him during regular visits at the federal correctional institute in Texarkana, Texas. He also told him, “I did wrong, and when you do wrong, you’ve got to face it.”

You can dwell on negativity and anger and hurt, and you’ll slowly see yourself fade out of the picture, [or] you can take the step and make a difference.

Nelson did eight years. Adrian dealt with his absence by lifting weights, running track and becoming one of the most-sought-after football players in the country. That approach became a lifelong pattern: Whenever life kicked him, he worked harder, did better, as if adrenalized by tragedy, slights and slips. The Heisman snub, after he gained 1,925 rushing yards his freshman season at Oklahoma? The collarbone he broke twice in his junior year? Just more motivation.

In the months before the 2007 NFL draft, Chris Paris, who was raised as Peterson’s brother and with whom he was extremely close, lived with the running back in Oklahoma. Paris was trying to turn his life around, but the night before the scouting combine, he was shot and killed in Houston. The next day Peter-son scribbled Chris’s name on his cleats and ran the 40 in 4.4 seconds. “I just can’t stay down in a funk,” Peterson says. “You can dwell on negativity and anger and hurt, and you’ll slowly see yourself fade out of the picture, [or] you can take the step and make a difference.”

The fragile label that led some NFL teams to doubt his pro prospects? Peterson, drafted seventh by Minnesota, won AP Offensive Rookie of the Year. His torn ACL in 2011? Peterson returned in nine months, was named MVP and nearly broke the single-season rushing record with 2,097 yards. “All mind-set,” he says. “Faith.”

For Peterson, it’s possible to view child-abuse allegations and a lost season the same way he viewed a broken collarbone: as an obstacle to overcome. The week before training camp opened this season, Peterson summoned a tattoo artist to Houston. He had been researching online and came across Ephesians 6:10-18. It reads, in part: Put on the full armor of God, so that you can take your stand against the devil’s schemes. For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world.

Over two days, through two 12-hour sessions, Peterson had body armor inked from his chest to his shoulders, along with the words shield of faith over his heart. His scars, the deaths of loved ones—for his whole life he had been armoring himself to deal with the world. The tattoos remind him every day of that. As he lay there, he was readying both for the NFL season and for what he calls the “spiritual battle” yet to come.

Nov. 20: Eden Prairie

I feel like when you know someone is innocent, then you should stand by that. But in this world it’s not about that. It’s about people doing what’s going to make them look good.

“I thought about retirement. I was serious, man. It was just like an emotional roller coaster that I was going on. Being angry with the NFL for how things were handled, with the organization and the judicial system as well. . . . After I’m like, O.K., I finally got this behind me, they come back and switch it up. I was like, Wow. It just went to show how politics and how people will cover themselves. . . . I feel like when you know someone is innocent, then you should stand by that. But in this world it’s not about that. It’s about people doing what’s going to make them look good.”

At his lowest points during his exile, Peterson wanted to quit football. Inside the Vikings’ cafeteria one day this fall, Peterson, whose mother was a high school state track champion, detailed the backup plan he hatched: He wanted to become an Olympic sprinter. He was serious, too. He met with Michael Johnson, the four-time gold medalist, in Dallas. Another world champion, Maurice Greene, offered to help him train.

During his suspension Peterson decamped to Texas with his wife, whom he met at Oklahoma and married in July 2014. Adrian, Ashley and their oldest son, Adrian Jr., who was born in 2011, split time between his homes outside Houston and in Palestine. They visited Disney World and Yellowstone, threw a birthday party for Adrian Jr. and binge-watched specials on the History Channel and The Real Housewives of Atlanta.

Black Monday Snaps: Giants' best options for replacing Tom Coughlin

Peterson turned 30 last March. Ashley was pregnant with their second child, another boy, due in October. He had decided to return to football, but he didn’t want to stay in Minnesota, where he was under contract through 2017. His family members felt the same way. They wanted him to play closer to home, for Dallas or Houston, especially with another baby on the way. They were livid with Kevin Warren, the Vikings’ chief operating officer, who they believed had worked in concert with the NFL to keep Peterson sidelined. Says Ashley, “I wanted to start over somewhere else.”

MMQB: The impact of Concussion on moms and dads

Peterson faulted the front office for “not respecting my reasons for wanting a change of scenery,” but he did not blame coach Mike Zimmer or his teammates. He rejoined the team in June for OTAs. “It felt like the storm was passing,” Peterson says. “I wasn’t walking in shameful or anything like that.”

He had spent much of his exile thinking about fatherhood. In some ways he enjoyed the time off: sleeping in, working out, not feeling sore, taking Adrian Jr. to school—a glimpse of what life could be like in retirement. But Ashley saw her husband’s hurt. “I’d never seen him like that,” she says, “as quiet and as down.”

To Peterson, how outsiders view his case is an indication of a cultural misunderstanding. He says he disciplined his child the way his parents disciplined him, which is the way many parents punished their children where he grew up. No one there called it corporal punishment or child abuse. They called it parenting, even good parenting. That’s why Peterson scoffs at the notion of redemption, because he doesn’t think there’s anything for him to redeem. “That’s our culture,” Nelson says. “My son is 30, and he’s a grown man, and a millionaire, and he’s never told me to shut up. That’s the respect he has for his parents.”

In Palestine, a town of 18,000 in East Texas, Peterson had a community that believed he had taken a stand for their values and rights. They held a parade in his honor last June, where hundreds stood in line for an hour to shake his hand and told him to forget about the haters.

Peterson hasn’t explained himself much to outsiders beyond the statements he released. Explanations, he says, end up sounding like excuses. And he is cognizant that wide swaths of Americans don’t feel the way he does—people like Dr. Robert Sege, a board member for Prevent Child Abuse America. Sege says the board does not recommend spanking under any circumstance, and adds that the photographs he saw from Peterson’s case “weren’t ordinary corporal punishment—they really crossed the line into abuse.”

MMQB: The unfamiliar role of Vikings star Adrian Peterson

Peterson says that through counseling he learned other methods of discipline. He says he’ll never use a switch again. Sege, who has no direct connection to Peterson’s case, describes Peterson acknowledging his mistake and changing the way he parents as “terrific progress,” whether Peterson calls what he did abuse or not.

Peterson does not put the whuppin’s he endured as a child on the long list of obstacles he’s overcome. To the contrary: Discipline, he says, is not part of his success, but the key to it. “That discipline is embedded in me,” Peterson says. “It’s the reason that I am where I am.”

Nov. 15: Oakland

This is what it’s all about. Loving your kids.

“[Having another child] was just more confirmation. Like, Hey, this is what it’s all about. Loving your kids. Teaching them what’s right, what’s wrong. These people are the ones that are now your family. . . . Family first. Because when everyone else leaves you, your family is going to be there. . . . Every time I went to court, my wife was right there. When I was home and I needed someone to talk to, or I was having my rough days, my wife was there with me, my family was there with me.”

In the early morning hours before the Vikings hosted the Chargers on Sept. 27, Ashley went into labor. Peterson’s mother drove her to the hospital while he slept. Peterson arrived there shortly after 8 a.m. His status for the game remained unclear. “Will you make it?” Zimmer texted him.

“I’ll get back to you,” Peterson responded.

Zimmer sent another text an hour later. “I’ll be there,” Peterson tapped back.

Axyl Eugene Peterson was born shortly after 9 a.m. Peterson told Ashley she looked pretty and cradled the newborn in his arms. He then sped to TCF Bank Stadium, arriving 90 minutes before kickoff. He felt energized and, in his 100th career start, rushed for 126 yards and two touchdowns in a 31–14 win.

As the season continued, Peterson targeted 2,500 rushing yards, an outlandish goal that would have crushed the single-season rushing record the way Peterson crushes every single hand he shakes. The fallout from his legal issues, Peterson says, was “always back there, on the last shelf, tucked under a lot of other stuff.”

He had run for only 31 yards on 10 carries in the opener, a loss to the 49ers. Teammates took their cues from Peterson in the weeks that followed. They watched him scream at himself in practice. They saw him pull aside kicker Blair Walsh after a shaky start and tell Walsh that he had “greatness in his eyes.” A “father figure,” Kirby Wilson, his position coach, called Peterson, unaware of how that might sound.

Peterson continued to move forward, his focus on this season, not the last one. So did the Vikings. “Whatever crime, or however people view it, it had been dealt with,” Wilson says. “We don’t talk about it, because it’s done.”

After losing to Denver in October, the Vikings won five straight. In Weeks 7 through 10, Peterson gained 98 yards against Detroit, 103 against Chicago, 125 against St. Louis and 203 against Oakland. With that performance Peterson tied O.J. Simpson for the most 200-plus-yard rushing games in NFL history, with six. As the sun set on O.co Coliseum, fans with faces painted purple and Vikings helmets atop their heads cheered him until they lost their voices. Peterson sealed the game with an 80-yard touchdown jaunt—one cut, then, poof, gone.

After the locker room had emptied, Peterson said it was moments like this that he came back for. Walsh made 17 straight field goals after Peterson’s pep talk. Peterson said this team reminded him of the 2009 Vikings, who made it to the NFC championship game.

Peterson was the last player to leave the locker room. As he packed his suitcase, he said what he believes: that God tested him in order to reward him, that he went through last year to get to this year. “Look at me now,” he said. “I’m still breaking through. I was the most hated person, but I kept my faith.”

Dec. 2: Eden Prairie

My dad was here [for Thanksgiving]. His wife. My brother. My mom. Just like the immediate family. It was just good being around family, and being able to relax. . . . I kind of opened it up, telling everybody that I’m thankful that they’re there, friends that are there as well. For how family always has your back. . . . It was Thanksgiving, I was just telling everyone what I was thankful for.

Eleven days after the Raiders game, the Petersons hosted Thanksgiving at their house in Minnesota. They fried two turkeys and devoured greens and stuffing and sweet-potato pies. Before dinner they took turns going around the table to say what each person was thankful for. Peterson went first.

His son from the abuse case was there. For much of the 2014 season and last off-season Peterson says he was not allowed to see the boy, per court order. He recalls one phone conversation during their forced separation.

“I love you,” he told his son.

To which his son responded, “I love you too, Dad. Can I come over to your house?”

Beginning last June, Peterson was allowed to see the boy on supervised visits. Eventually unsupervised and overnight visits were permitted, though Peterson says he still must inform his therapist beforehand. He spent this season reconnecting with the boy. “The amazing part is watching him around his brothers and sisters like nothing has really changed,” Peterson says. “I noticed that that’s something that he needed.”

Peterson also thought about his legacy, on the field and off. On Sunday he became the first back 30 or over to win the rushing title since Curtis Martin in 2004, and he’s just the eighth player in league history with at least three rushing crowns. But Peterson thinks too about the games he missed and the statistics he would have accumulated. And of how his suspension may have extended his career: He says his year away saved his body from between 400 and 500 hits. “This season is another example of how super elite AP is,” says Brett Favre, who played with Peterson in Minnesota in 2009 and ’10. “It can be magical to watch him run. I’d put him in the top few teammates I’ve ever played with. Guys like him and Reggie White.”

Peterson, who now has 11,675 career rushing yards, cares deeply about his place in football history. He says he wants to play “seven or eight” more seasons. “The greatest to ever do it, that’s what I want,” he says. “There will be guys that come around that people will compare to me, like how they compare Kobe or LeBron to Jordan. Look, Jordan was the best. You haven’t seen anyone like that since.”

His body stiffens. His eyes narrow. “There won’t be another Adrian Peterson,” he says. “There will be a guy that reminds you of me. But there will only be one me.”

Peterson knows that his football legacy will be complicated by the events of 2014. He doesn’t think it should be. His says his development as a father should not—does not—correspond with his exploits on the field. He wants to be judged away from the field by the totality of his actions. He wonders why so many focus on switches and courtrooms, and so few talk about the AD Elite AAU girls’ basketball team he sponsors in North Austin, Texas, the one that has helped 27 players obtain athletic or academic scholarships since 2011, according to its coach, Steve King.

His father and his wife say they have seen Peterson tighten his circle of associates. He’s less trusting, they say, and more aware of what he says. “I’ve seen so much growth in Adrian as a man,” his father says.

Is that true? Peterson is asked. “I struggle,” he says. “I’m human. When I look back on my life, and the personal things I have encountered, it’s like, when you’re living a life of sin, bad things happen, no matter how much you have God in your life.”

What do you mean by that? “Just struggling in life and struggling on the field,” he says. “I had to commit my life to God. I’m on that side now. This is what happens when really, in your heart, you say, O.K., I’m going to do things the right way.”

Dec. 1: Eden Prairie

“After I visited Skyler, I sat there and looked at Adrian Jr., just sad, to see my son and a kid the same age, and see my son just running around, going crazy. It had me thinking about life.”

Back in the Escalade after leaving Skyler’s house, Peterson pulls out his cracked iPhone and shows videos of Adrian Jr. singing along to Michael Jackson, belting the Vikings’ fight song, karate-kicking his way across the living room. “My dad says I had more energy than he does,” Peterson says. “I’m like, How is that even possible?”

Three weeks later Skyler died. He is buried in his signed Peterson jersey with an autographed football in hand, after receiving assurances from his father that TVs in heaven will show Vikings games. Peterson is again reminded of the fragility of fatherhood, of life. His son, the one from the abuse case, continues to visit him. “Their relationship,” Ashley says, “that’s what matters.”

Peterson passed the rest of the ride home from the Elferings’ in silence. The SUV parks in his driveway and he heads inside, where it matters little what the world thinks of him, whether he’s forgiven or understood, considered changed or unrepentant. Adrian Jr. is waiting to greet him with a hug. “Hi, Dad,” he says.

Greg Bishop is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated who has covered every kind of sport and every major event across six continents for more than two decades. He previously worked for The Seattle Times and The New York Times. He is the co-author of two books: Jim Gray's memoir, "Talking to GOATs"; and Laurent Duvernay Tardif's "Red Zone". Bishop has written for Showtime Sports, Prime Video and DAZN, and has been nominated for eight sports Emmys, winning two, both for production. He has completed more than a dozen documentary film projects, with a wide range of duties. Bishop, who graduated from the Newhouse School at Syracuse University, is based in Seattle.

Follow GregBishopSI