Unleash It Deep

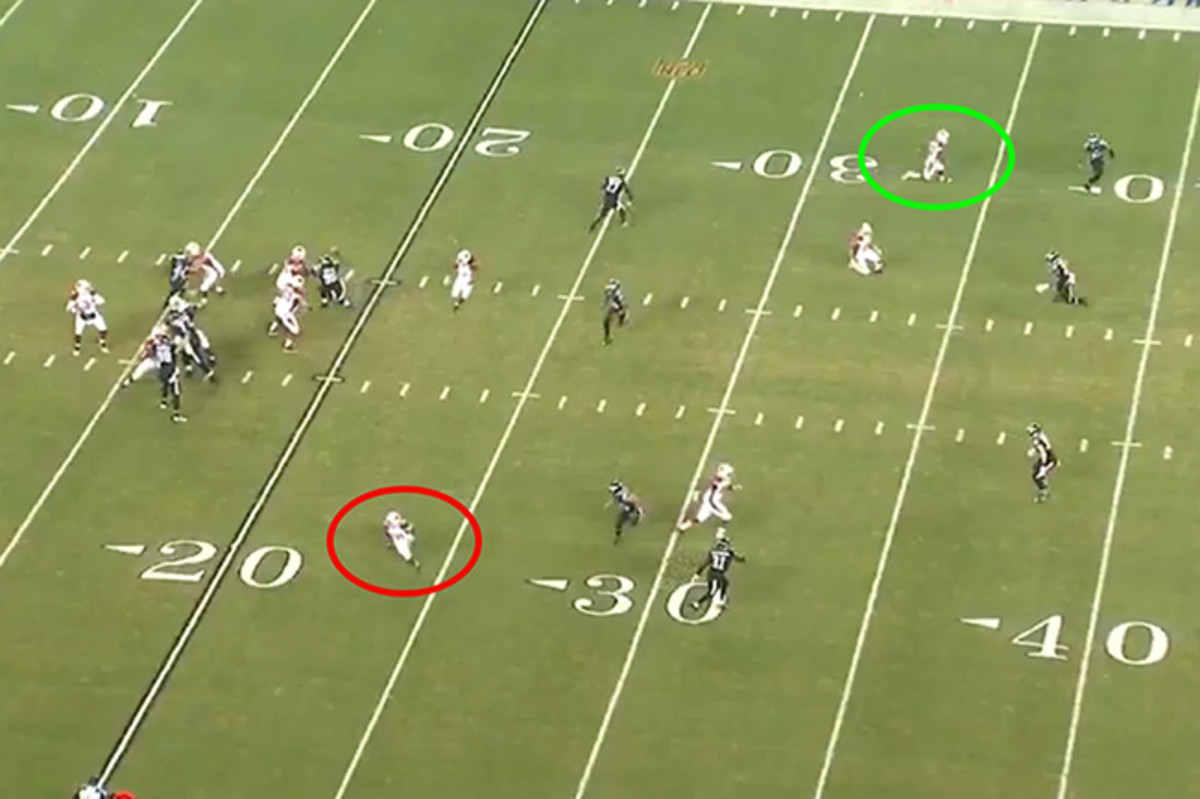

TEMPE, Ariz. — Last month, on the first play of their win in Philadelphia, the Arizona Cardinals lined up with three receivers tightly bunched to the left side of the formation. At the snap, Carson Palmer jumped back into a five-step drop as his trio of wideouts—Larry Fitzgerald, Michael Floyd and John Brown—shot in separate directions. As they did, and much of the defense’s attention floated to that half of the field, rookie running back David Johnson leaked unnoticed into the right flat.

Getting Johnson, an exceptional receiver, isolated in that area of the field was the play’s central purpose, and instantly the design was a success. On the opening snap of the game, most quarterbacks would be content to take the simple completion, gobble up that first easy throw as a way to light the fuse. But the Cardinals are rarely interested in a slow burn. Rather than dump the ball to Johnson, Palmer uncorked a throw for Brown streaking down the field.

“We’re looking for the chunks,” Harold Goodwin, Arizona’s offensive coordinator says of the play. “You can nickel and dime them all the way down the field, but we’re trying to shorten the field or even score on one throw.”

That the perfect throw ricocheted off Brown’s hands to the ground—a gamble with no return—only emphasized how the collective decision, between play-caller Bruce Arians and quarterback Carson Palmer, exemplifies what has been a defining element of NFL offenses in 2015.

In recent years, offenses that have set the standard across the league were built with shorter throws. The 2013 Broncos, who broke the single-season points record, finished with the 26th-deepest throws, on average, in the league. In 2010, when New England had the most efficient passing game in football, the Patriots were also 26th. At their core, the Broncos and Patriots had offenses built to score gobs of points by manufacturing first downs, a gradual pulling at the fibers of a defense before they eventually split. The Cardinals rip through it all at once.

In the past, deep throws were often the tool of less-talented teams looking for a means of leveling the playing field, but this season some of the most fear-inducing offenses in football lived on a steady diet of the deep ball. The top five finishers in average air yards per throw in 2015 included the Panthers (first), Cardinals (second), and Steelers (fifth), three playoff teams with considerable striking power. And on passes at least 30 yards downfield (twice the distance that defines a “deep” throw), Pittsburgh comfortably led the league.

Teams have had disparate reasons for embracing the deep ball—continuity, identity, necessity—but the end result is the same. The chances are there, and they’re going to take them.

* * *

It was early in the morning of an October day in 2014 when Ben Roethlisberger tapped quarterbacks coach Randy Fichtner on the shoulder. A few days earlier, the Steelers had been on the receiving end of a 31-10 drubbing in Cleveland, a loss that happens on a Haley’s Comet-like cycle. Roethlisberger wanted Fichtner to grab the bag of balls and meet him on the practice field before the offense’s walkthrough. Oh, he added, and bring the buckets.

Pittsburgh’s deep passing drills involve a makeshift contraption consisting of two gray industrial-sized Rubbermaid trash cans glued bottom to bottom. The top can, outfitted with a Steelers sticker, has a hole about one foot in diameter cut into the side that lets Fichtner easily retrieve any ball that manages to find its target.

For 20 minutes, Fichtner moved the buckets up and down the sideline as Roethlisberger tossed fades and go routes. Before they finished, he’d thrown 100 passes. Against the Browns, Roethlisberger had missed on four downfield throws, including an underthrow to Antonio Brown and an overthrow of Markus Wheaton, both in the end zone.

“Those are just long incompletions,” Fichtner says. “The crowd goes from, Oooooh to Boooo. Then it’s second- or third-and-10, and then you’re off the field.”

• WILD-CARD WEEKEND BREAKDOWN: The MMQB’s Andy Benoit on who has the X’s and O’s advantage.

A return to the buckets was the quarterback equivalent of a golfer’s trip to the range, a way to refine a rhythm lost during a stretch of the season when technical work gives way to schematics. For the remainder of the 2014 season, the Steelers were among the most dangerous deep passing teams in the league during an 8-2 finish that propelled them to the playoffs.

“Ben’s always been a guy who’s liked to attack down the field,” Fichtner says. “That’s how he kind of grew up in his early days with the Steelers. Where he’s kind of done a better job and where he maybe takes more advantage is that he’s worked extremely hard at throwing the deep ball.”

Roethlisberger’s fine-tuning likely helped, but Martavis Bryant making his professional debut the following week certainly didn’t hurt. Watching Bryant in college, offensive coordinator Todd Haley—a wide receivers coach by trade—loved what he saw. “I was standing on the table the round before we took him,” Haley says of the 2014 fourth-round pick. A lack of refinement kept Bryant on the bench early as a rookie, but it was clear to Haley and everyone else that what they’d seen on Clemson’s film wasn’t a mirage. “There wasn’t a day he went by that he didn’t make a play where all of us were just like, ‘Whoa,’” Haley says. “It was just a matter of getting him to understand he had to do it the way he was supposed to do it. He had to be where he was supposed to be. He couldn’t make mental errors.”

After serving a four-game suspension to start the 2015 season, Bryant exploded: 50 catches for 765 yards and six touchdowns in just 12 games. Folding a 6-4 receiver that runs like a deer into the offense has given Pittsburgh a new dimension the past year and a half, but to a man the Steelers insist the system hasn’t been altered to include more deep throws. Most of the concepts have remained the same. Names of plays haven’t changed.

“I feel like we take advantage of the moment when it presents itself,” Bryant says. “We don’t go into the game saying, ‘We’re just going to throw go balls the whole time.’ Once Ben sees the matchup that he likes, he’s willing to take advantage of it.”

What has changed is the amount of time Haley, Roethlisberger and others have spent together. This is the fourth season of the Haley-Roethlisberger relationship; after a tumultuous start, the pair couldn’t be more in step. Often this year Haley will blurt a play into the headset just as Roethlisberger suggests the same one. His only reaction is to smile.

Streamlining communication has been a goal of Haley’s since his early days as a coordinator with the Cardinals. His first season in the desert, Arizona’s quarterbacks coach and wide receivers coach had a combined zero years of NFL coaching experience, which led Haley to deploy a new approach to the team’s offensive meetings. Rather than gather separately, the two positions met together, and that practice has carried over to Pittsburgh. The past two years he’s even gone a step further. Last season Haley ceded control of the team’s drills to Roethlisberger, who has used them to tweak specific route concepts and timing issues he thought needed work.

“I have such great trust in Ben, so I said, ‘You run it,’” Haley says. “And that communication that’s going on between those guys every day during that period has just paid huge dividends. As a coach, that’s hard to do sometimes. But I know we’ve got something special here.”

Connections have been made across the offense, but at times Roethlisberger and Antonio Brown appear to exist on a higher plane of consciousness. On a deep completion during a shootout loss in Seattle in November, Roethlisberger let rip a 50-yard cannon shot as Brown ran in-step with not one but two Seahawk defenders. “He trusts me,” Brown says. “He knows that if he gives me a shot, I’m going to take that opportunity to make a play. That’s the kind of chemistry you want with your quarterback. That type of trust that even with two guys on you, he can still let it fly, and that a jump ball is nothing.” Roethlisberger missed four games and part of another during a season in which Brown still had 136 catches for 1,834 yards and 10 touchdowns. If the pair had played together for 16 games, Brown might have obliterated every receiving record.

• NOBODY WANTS TO FACE THE STEELERS: What makes Pittsburgh the most dangerous team in the AFC bracket.

The depth of faith everyone in Pittsburgh has in the passing game makes risks commonplace. According to Football Outsiders’ ALEX, a stat developed this season by Scott Kacsmar to measure a quarterback’s aggressiveness on third down, Roethlisberger is more ambitious in those situations than every other quarterback but one since 2006. On average, his third-down targets traveled 6.5 yards past the sticks. No other quarterback topped 4.4. For Fichtner, that mindset again boils down to the belief Roethlisberger, Brown, and everyone else have forged in each other. “They see things, and they rely on each other to see and feel the same thing,” Fichtner says. “And that’s where the ball might be potentially thrown in a spot where, on paper, it shouldn’t be.”

• STEELERS PLAYOFF PREVIEW: Peter King’s One-Minute Drill video on the postseason key for Pittsburgh

* * *

Basketball’s three-point revolution, in part, has come down to simple math helping decision-makers overcome long-held principles. An excellent midrange shooter in the NBA hits jumpers about the half the time. A slightly below-average three-point shooter makes good from behind the arc about a third of the time. The gap between 33 and 50 percent looks massive, but at those rates the output is the same.

The trade-off isn’t exact, but there are some teams in the NFL, like the Panthers, who’ve unwittingly taken a similar view. Throws of 14 yards or less were hauled in, on average, 71.3 percent of the time in the league this season. Deep throws, 15 yards or more down the field, were caught on just 42.7 of throws. Again, at face value that’s a precipitous drop-off, but Ted Ginn is a perfect example of why the lower-percentage play is still worth taking.

• STEPH CURRY SAYS CAM IS MVP: The friendship between the Panthers QB and the NBA’s biggest star.

On throws at least 15 yards downfield, Ginn had the second-highest drop rate in football, at 13.9 percent (only Davante Adams was worse). Ginn also hauled in nine such passes, a disproportionately high number considering how infrequently Carolina throws. The most important number, though, is 40.78. That was Ginn’s average gain on deep receptions this year. It was the highest mark in the NFL, and it meant that on average, once every two games he took the Panthers from their own 20-yard line to field goal range on a single play. As other teams chipped away at drives, Carolina could conjure one out of thin air.

Personnel played a part in dictating the Panthers’ style of offense. Top wideout Kelvin Benjamin wasn’t a precise underneath target to begin with, but losing him to a knee injury before the season left Cam Newton with one of the league’s least nuanced groups of wide receivers. Mike Shula responded by creating a set of throws—often off play action—that involved either launching the ball downfield or using tight ends and running backs to exploit the areas near the line of scrimmage.

In a way, Ginn is to the Panthers’ offense what a player like Doug McDermott is to an offense-starved team like the Chicago Bulls. Their deficiencies are glaring—Ginn with his drops, McDermott with his defense—but their values, Ginn as a deep threat and McDermott as a deep shooter, are enough to make them part of the game plan. For both, that value propels a cycle of offensive efficiency. McDermott’s placement behind the arc creates space for driving lanes, which leads to defenders being forced to help, which leads to more open shots and a growing fear of him as an outside threat. Defenses having to respect Ginn as a threat down the field pull a defender out of the box, which fuels the running game, which makes defenses even more susceptible to shots taken off play action. That cycle explains how Newton and a ragtag group of receivers produced the ninth-best passing DVOA (Football Outsiders’ catch-all metric for efficiency) in football and the eighth-most efficient offense in the entire league.

• PANTHERS PLAYOFF PREVIEW: Peter King’s One-Minute Drill video on the postseason key for Carolina

* * *

For Arizona, it was never a matter of growing or falling into an offense reliant on deep throws. Going downtown is in the Cardinals’ bones. When Bruce Arians was a quarterback at Virginia Tech in the mid-’70s, the Hokies ran the Wishbone offense. Watching the huge gains that run-oriented formation created through the air, Arians fell in love with taking shots down the field. “It was the easiest passing game in the world,” he says. “Hard play action, throw it down the field, the guy’s one-on-one all the time. [My offense] kind of evolved from there. Our play-action stuff has a lot of that flavor to it.”

Each stop Arians has had as a play-caller, his teams have been defined by a tendency to go long. Since 2007, the lowest finish an Arians offense has had in air yards per attempt is 10th, and every other season they’ve finished in the top five.

During the 2015 preseason, Arians ceded play-calling duties to offensive coordinator Harold Goodwin. It's been yet another lesson that Arians won’t stand for an offense that plays scared. “Against the Saints, in the headset, at halftime, he’s harping on me, Throw the ball down the field. Take shots,” Goodwin says, mimicking Arians’ growl. “He just believes you have to keep the pressure on the defense.” Backup quarterback Drew Stanton, in his fourth year under Arians, managed to avoid a similar chiding when he stepped in for an injured Palmer last season. “I made sure to take every single shot possible, because I know I was probably going to hear from him,” Stanton says, laughing. “That’s the beauty of the offense. You push the ball down the field, and you feel comfortable with what you’re seeing.”

What’s struck Stanton most about Arians, though, something that goes all the way back to his first year with him in Indianapolis, isn’t a willingness to play this way. It’s his ability to build an offense that can do it in so many ways. The bombs come in a never-ending array of packaging. Receivers can head down on the same side of the field, as Brown did on the opening play against Philadelphia. They can sprint across it, as J.J. Nelson did on his long touchdown against the Bengals. Arians can use David Johnson tearing down the seam as a way to hold the safety on a long Nelson touchdown, as he did against the Rams in St. Louis.

When Brown, a 5-9 speedster, got to Arizona, he was in heaven. (“[Bruce] likes fast Smurfs,” says Cardinals general manager Steve Keim. “John Brown was the epitome of Bruce Arians’ old vision.”) Slowly, Brown started to appreciate the intricacies of how he was tearing away for 60-yard touchdowns.

Arians is a master at using geometry to exploit a defense. Routes are designed specifically with end points to create equilateral triangles with three receivers. “I actually really saw it, and I’m like, ‘Wow, I never knew that,’ ” Brown says. “Any way he can do it, he can get it done.” The result is the maximum possible strain on a team’s coverages, and with a lot of Arizona’s plays, that coverage often doesn’t matter.

“Angles and spacing,” Floyd says. “Spacing is a huge thing for us. The right spacing, it might be a foot that you have to make with a defender, but that one foot can separate you.”

Several members of the Cardinals’ offense admit that for the first season—and then some—there was an acclimation period. “In the risk-taking and the play-calling and so many different ways,” Carson Palmer says. What’s happened in the two years since is that all the dominos have fallen to give Arians the perfect vision of what he wants his offense to be. “Our first offensive meeting of the year, I could remember telling the guys that in my 12 years in the league, this is the most talent that I’ve been around,” Goodwin says. Keim knew when he took the job that the offensive line was a priority, and acquiring players like left tackle Jared Veldheer and left guard Mike Iupati has afforded Arians both the time to take the chances he covets and an improved running game that only adds to the potency of Arizona's play-action attack. Arians embracing a new type of receiver and Larry Fitzgerald embracing a new type of role gave the Cardinals a unique middle-of-the-field threat. And with Brown and Nelson, another of the Smurf brethren, the Cardinals have even more pop outside the numbers.

“When you look at us schematically—when we’re on our game, who do you stop, and how do you stop us?” Keim asks. “If you’re going to take away the vertical passing game, then we’re going to throw it to David Johnson. It’s fun to watch, especially to watch it all come together.” The final product is an offense that finished third in passing DVOA and fourth overall.

The cache of weapons is a necessary element to that type of destruction, but with each game, the single defining move of Keim’s tenure comes into focus. It took two late-round picks for the Cardinals to pry Palmer away from Oakland. Keim was always in awe of Palmer’s abilities as a passer, but what even he can’t believe is how the 36-year-old learned new tricks—like working on his pocket mobility to allow even more shots downfield—over an offseason that included rehabbing a second ACL tear. “That blows everything out of the water to me,” Keim says.

• CARSON PALMER: A QB AND HIS GAME PLAN: PART I & PART II

Even if Palmer says it took some nudging to truly embrace the mentality his new head coach demands, Arians assures that it didn’t take much. “I never had to do that with him,” Arians says, chuckling. “He likes throwing it downtown, and that’s why we got him. He’s one of the best deep-ball throwers I’ve ever seen. There are still times when it’s like third-and-three, and we’ll have a choice route wide open, and he’s taking a shot down the field. It’s usually right on the money and we’re completing it, so I can only bitch for a second.”

The season before he arrived in Arizona, Arians was at a point in his career that mirrored Palmer’s final days in Oakland. He was 60, and he refused to bend to what others in the Steelers’ organization wanted from the offense. “He has a hard time letting people dictate who he is or what he’s about,” says Goodwin, who’s been with Arians since 2007. “I think that’s one of the reasons the Pittsburgh thing went awry. They wanted a certain thing, and that’s just not his personality as a play caller and as a coach.” Higher ups in Pittsburgh were worried that Arians’ desire to throw the ball down the yard was putting their high-price quarterback in harm’s way. “Now, they’re doing the same thing I got fired for,” he says.

What Arians accomplished the next year in Indianapolis, stepping in for cancer-stricken Chuck Pagano and taking the Colts to the playoffs, finally got him his chance in Arizona. That chance came late enough in life that it’s only exacerbated his tendency to play how he wants. “He’s like Jim Carrey in Liar, Liar,” Keim says. “He doesn’t tell you what you want to hear. He doesn’t have to be nice to you. He’s just him.

• CARDINALS PLAYOFF PREVIEW: Peter King’s One-Minute Drill video on the postseason key for Arizona

Keim is 43 years old, with four kids under the age of 9. As he says, he needs this job. “Part of what fuels me and makes me do a good job is the fear that I’m going to get fired every day, the fear that this isn’t good enough. Maybe I use that as motivation. Bruce thinks to himself, ‘I’m 63. I’ve got a house on the lake. I don’t need any more money. I can go sit on that boat with a cocktail and be happy, and tell everybody to kiss my ass.’ He does this because he loves it, he’s good at it, and he’s got an unbelievable feel for calling a game.”

The way he calls it, rooted in a philosophy that the juice is worth the squeeze, has permeated how an entire organization thinks about offense. Arians has always been driven by the idea that the risk is worth the reward. For his Cardinals—as well as Pittsburgh and Carolina—that ethos has put the ultimate reward within reach. Calling a game used to mean gathering kindling and stoking a crackling flame. On the eve of this year’s playoffs, Arians stands with a match and a bottle of kerosene. And he’s not afraid to use them.