Think Super Bowl 50 will be huge? Imagining the 100th edition

Special Report From The Future: As Super Bowl 100 played out in all its enormity last night, Super Bowl 50 looked tiny by comparison, the way the Earth now looks to our colonists in space. Yet it’s instructive to look back on that long-ago spectacle in San Francisco to see just how far the game has come, and society with it.

Fifty years ago, when the Super Bowl was still a modest spectacle watched in a single medium, played by a single gender, contested exclusively by teams from the U.S. and ignored by much of the rest of planet Earth, the title game was nevertheless called a “world championship” by the National Football League, whose very name betrayed a parochial, one-nation interest in what most of the world’s inhabitants knew—if they knew it at all—as “American football.”

That was in 2016, when the NFL was a quaint pastime with relatively low stakes, officiated by human beings who flipped a coin to start every game, used lengths of chain to measure first downs, blew whistles to halt play and threw yellow handkerchiefs to signal penalties. So primitive was the technology of that benighted age—typing with opposable thumbs was our principal form of communication—that NFL players practiced against stuffed dummies.

In many ways that world was an inversion of our modern planet. In 2016, people drove cars; in 2066, cars drive people. What we call reality they called virtualreality. In ’16, Earthbound people aspired to see the wonders of Mars; last night, Marsbound people longed for the wonders back on Earth, as the NASA and SpaceX colonists lamented the 14-minute broadcast delay of Super Bowl 100, played 140 million miles away in a desert landscape stranger than any on the Red Planet.

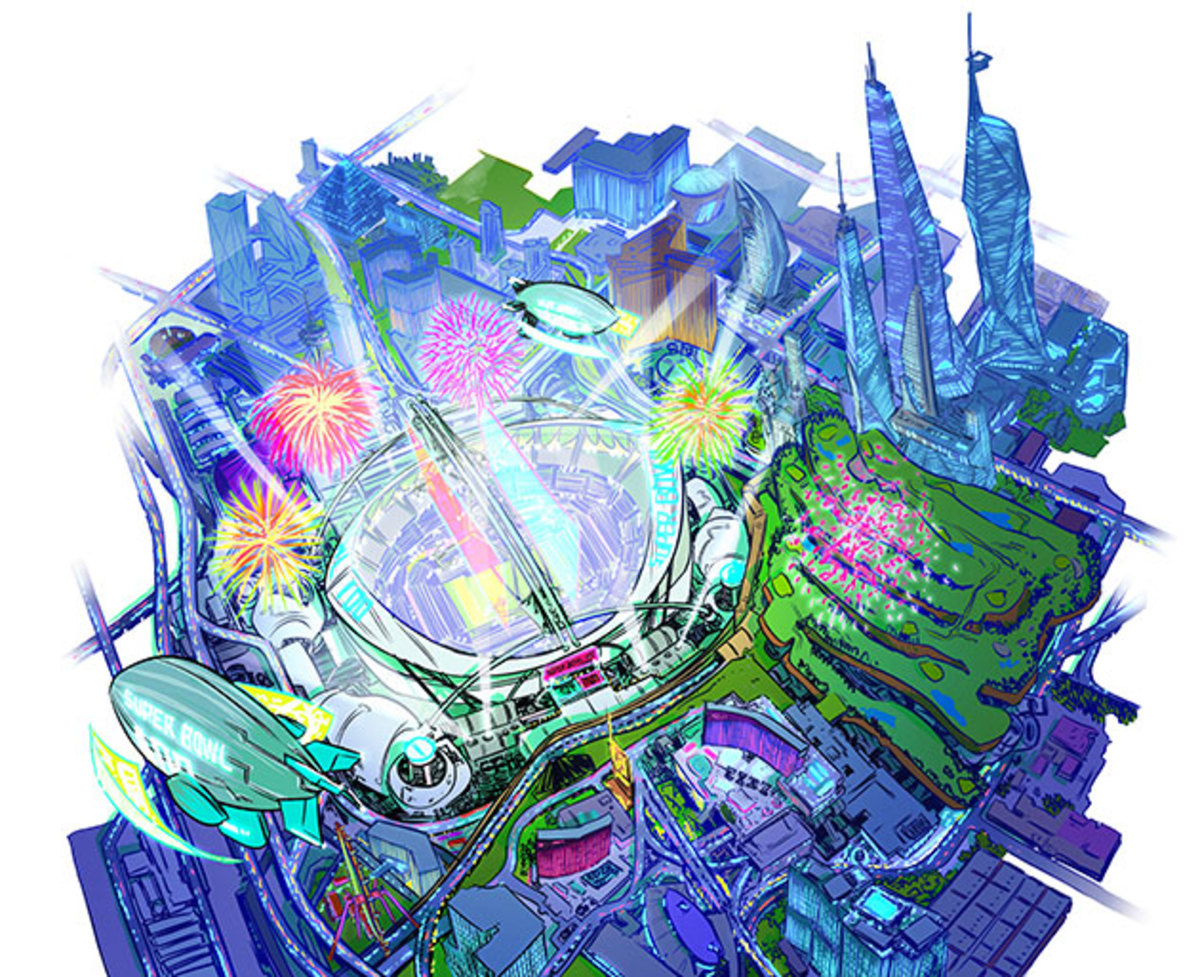

For its centennial Super Bowl, the NFL returned to its favorite host city, Las Vegas, which first staged the title game 45 years ago. Super Bowl LV, elderly readers will recall, shared its initials with Las Vegas but also with Louis Vuitton, the luxury brand that paid handsomely to cover game balls in its handbag leather, embossed with its logo. Thus began the long-standing and lucrative practice of pimping out the football, in every sense of that phrase.

Look for new entries in the Super Bowl 100 series, presented by Gatorade and Microsoft Surface, at SI.com/SB100 and Wired.com/SB100

Chapter 1, Oct. 7 TRAINING

Chapter 2, Oct. 28 EQUIPMENT

Chapter 3, Nov. 18 STADIUMS

Chapter 4, Dec. 9 CONCUSSIONS

Chapter 5, Dec. 16 MEDIA

Chapter 6, Dec. 30 VR

Chapter 7, Jan. 6 NFL IN SOCIETY

Chapter 8, Jan. 13 TRACKING

Chapter 9, Jan. 20 STRATEGY

Chapter 10, Jan. 27 SB 100

ROAD MAP TO

THE FUTURE

And though Super Bowl LV is now ancient history, 2021 remains important as the year that the NFL finally abandoned its nominal objection to sports gambling and awarded Steve Wynn the expansion franchise that became the Las Vegas Centurions. It was a pleasing coincidence that Super Bowl 100 would celebrate the century mark with the Centurions playing in their home stadium, the Macau Palace, which pops up like a Toaster Strudel from beneath Las Vegas Boulevard and retracts between games, turning the area back into a public plaza.

The Centurions’ opponent was, of course, AFC Barcelona, the American football subsidiary of the Spanish fútbol giant, which brought to the NFL a ready-made legion of loyal supporters. Those fans arrived by supersonic transport from all points of the globe—and some points beyond it—touching down both at McCarran International and at Nevada Extraterrestrial, the spaceport farther out in the desert, where some citizens alighted fresh from their homes in Bransonia, outer space’s first subdivision: a low-orbit Levittown for which the International Space Station served as a kind of model home. Most space-dwellers visiting Vegas for the first time said the pumped-in oxygen and solar-flare carpeting of the casinos were welcome reminders of home.

Even those who don’t miss this world said they wouldn’t have missed this game for the world. Fifty years ago, before Super Bowl 50 was played, experts predicted that human beings would still attend live events in 2066, even though they could be in the game from the comfort of their couches. “There’s still going to be something special about literally being there,” Jared Smith, the president of Ticketmaster North America, said in 2015.

He was right, of course, which explains all those people arriving at the stadium hours before kickoff in all the usual ways—by autonomous cars that dropped them off and then valet-parked themselves outside of town, but also on the transcontinental Hyperloop, gliding at 760 mph on a cushion of air through a low-pressure pipeline, as if each passenger were an enormous bank slip tucked into a pneumatic tube at a drive-through teller window in 1967. That was the year the first Super Bowl was played, midway through the first season of Star Trek, which was set in a space-age future that now looks insufficiently imagined.

And so hours before Super Bowl 100 kicked off—we persist in using that phrase, long after the NFL abandoned kickoffs—some fans were being dropped off by their cars a mile or more from the stadium, their fitness wearables synced to their car software, both programmed to make their owner walk whenever the day’s calories consumed exceeded the day’s calories burned.

And calories were comprehensively consumed. The pregame scene offered all the Rockwellian tableaus of the timeless tailgate: children “running” pass patterns on hoverboards (they still don’t quite hover, dammit); dads printing out the family’s pregame snacks; and grandfathers relaxing in lawn chairs with their marijuana pipes (grill smoke having been replaced by weed smoke as the dominant olfactory tailgate experience).

***

At the first Super Bowl, ushers tore tickets. At Super Bowl 50, they scanned them. At Super Bowl 100, fans were retina-scanned on the way in, their eyes swiped with Men in Black–style neuralyzers, except that these don’t erase your short-term memory. That’s the job of the $75 beers inside.

A mile away, on the Strip, an unshaven cohort of scalpers and touts offered the customary array of contact lenses guaranteed to fool any ocular-based biometric ticketing technology. To judge by their signs, every scalper offered “cheaper peepers” than the next guy, but these lenses were hardly inexpensive, given the global—and nominally interplanetary—interest in Super Bowl 100, which would be “experienced” in some way by a billion people, some of whom paid the $25,000-and-up face value to attend. (Still included: a complimentary seat cushion.)

Not every “ticket holder” required a seat. This innovation was predicted 50 years ago by Shawn DuBravac, chief economist for the Consumer Electronics Association, when he said, “In sporting events in the future, we’ll be able to upgrade and downgrade our seats throughout the game.” Standing-room fans of 2066 would be content, DuBravac noted, to watch the game on virtual-reality once inside.

At SB 100, eyes were swiped with neuralyzers, except these didn't erase your memory. That's the job of the $75 beers inside.

And so the VR headsets of 2016 gave way to the VR glasses of ’25, which led to VR contact lenses by the mid-’30s, which yielded to the implants of today, just as Ken Perlin predicted. Perlin, professor of computer science at NYU and a leader in the fields of multiperson immersive and mixed-reality environments, told Sports Illustrated before Super Bowl 50, “We don’t call it virtual reality—we call it future reality. Our language always evolves with technology. So in 1995, if someone was on a computer and you asked them what they were doing, they’d say, ‘surfing the web.’ Now they say, ‘reading.' "

In this same way, communication devices in every helmet in 2066 have made the huddle unnecessary, turning what we once called the no-huddle offense into just plain offense. Likewise, virtual reality (or future reality) has simply become our reality, and fans not content to stand and watch the game in what we once knew as VR can now purchase seats mid-game, whenever other spectators choose to vacate their locations and stroll around Super Bowl 100.

And yes, it’s Super Bowl 100. There was a time when the game would have been branded as Super Bowl C. Fifty years ago, at Super Bowl 50, the league ditched Roman numerals for a year, and it abandoned them for good at Super Bowl 88, when groundskeepers and graphic designers despaired of squeezing an unplayable Scrabble rack—LXXXVIII—onto each 25-yard line, not to mention onto T-shirts. So Roman numerals went the way of the Roman empire, which survives now most conspicuously in the sandaled Centurion on the home team’s helmets.

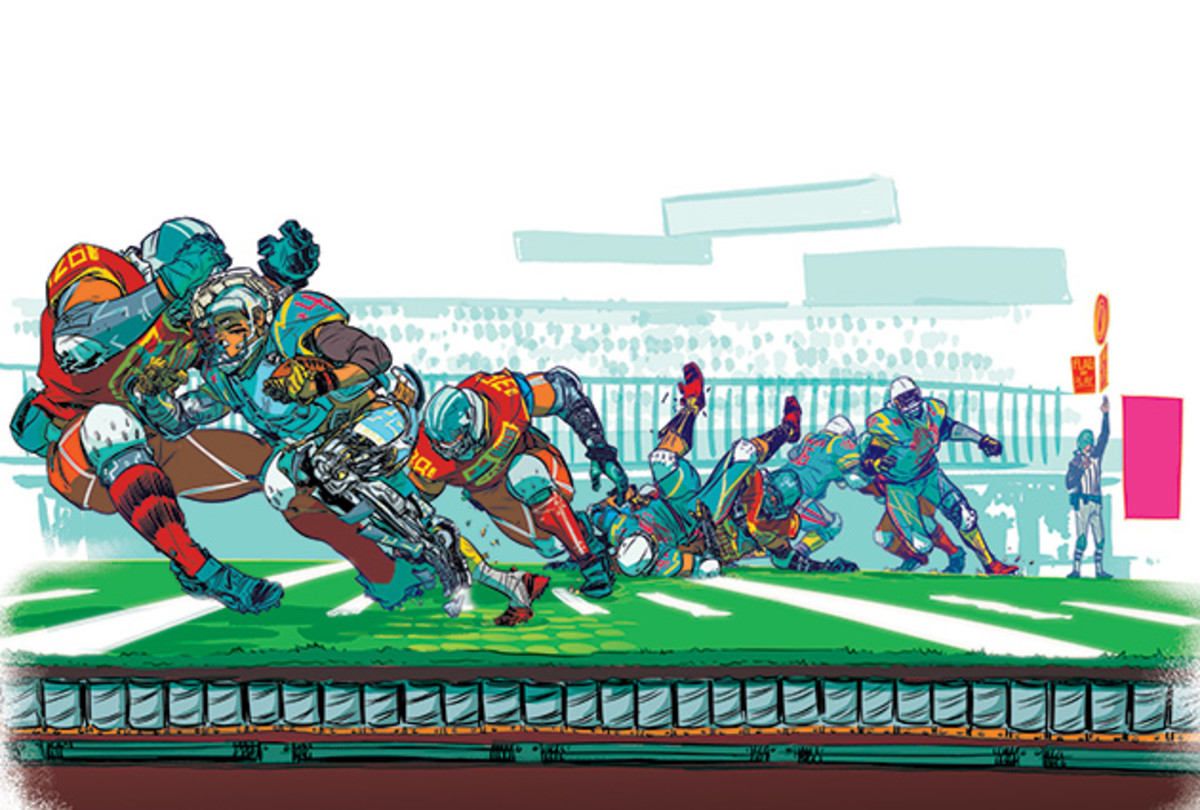

For years, people predicted a Roman-style fall for the NFL, over concussions and CTE. But there were other dystopian possibilities for the league besides extinction. Before Super Bowl 50, Travis Tygart, CEO of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, spoke of the possible future of performance enhancement. “We firmly believe that natural human competition—not having the best chemist—is what gives sport its inherent value,” he said. “But [being competitive] in 50 years won’t require just the best chemists. You’ll have to have the best heart-transplant surgeon who can give you the mechanical heart that will never fail, that will always be under control, even at exhaustion. You [will] end up literally having cyborgs—part human, part machine—competing.”

Mercifully, no man with a stainless-steel heart has yet participated in a Super Bowl, with the possible exception of Tom Landry. Still, the sheer volume of technology—the hardware and software—on these magnificent players, and at the fingertips of every coach, and built into every stadium and playing surface, was enough to make some people wonder before Super Bowl 100 if the game would really be contested between men or supermen (and superwomen).

As analytics became more sophisticated, game theory more prevalent and strategy more predictable, football threatened to resemble two supercomputers playing chess against each other—IBM’s Big Blue scarcely distinguishable from the Big Blue of the Giants. But that clearly hasn’t happened. “If you described to someone in the 1880s that there would be this sport called auto racing—when they didn’t yet know what an automobile was—they’d say, ‘That’s not a sport, that’s just technology,’ ” Perlin noted way back in 2015. “And it will be the same with football. What makes it a sport—what makes it compelling human drama—is that there is a person with a human heart and a human brain making decisions, performing brilliantly sometimes, and sometimes failing.”

To say that Perlin was right is an under-statement, of course, for we would see all of those things in Super Bowl 100.

***

The traditional flyover of military fighter jets in Las Vegas was preceded earlier in the week by Barcelona’s arrival via SST, which promises a maximum of nine hours from anywhere in the world to anywhere else in the world, at Mach 3, with a low sonic boom—a vast upgrade on the loud and long-abandoned Concorde, which had to fly, by law, almost exclusively over water. So Super Bowl 100 was also a celebration of the globe-shrinking technology that allowed the NFL to become a truly International Football League, as the two national anthems attested. After a holographic Jimi Hendrix played “The Star-Spangled Banner” on electric guitar—an homage to the first Super Bowl, played in the winter preceding the Summer of Love—the Catalan cellist Pablo Casals, who died in 1973, played “Els Segadors,” the anthem of the independent nation of Catalonia.

Game balls were dropped by drone into the still-sure hands of the honorary U.S. captain (73-year-old former Giants receiver Odell Beckham Jr.) and at the gilded feet of the international captain (78-year-old former Barcelona forward Lionel Messi), both men looking fit in middle age. Possession had already been assigned to Las Vegas for having the better regular-season record (17–3), and the Centurions chose to start with the ball at their own 20. The opening kickoff was purely ceremonial—like a first pitch in baseball—a vestige of the time when there were real kickoffs, and kick returns, and kicks carried out of the end zone.

Elimination of the kickoff had the benefit of reducing high-speed collisions and thus head trauma. But it simply wasn’t possible to eradicate concussions in professional football. So large was the public’s appetite for the game—and so lucrative to league owners—that the league had long since resolved to live with concussions and CTE while working to reduce them, which meant either the removal of helmets entirely or the engineering of a new helmet. Creating new materials—wonder substances that hardened on impact, materials that mended themselves—helped the helmet become part of the solution. When Centurions quarterback Kirk James was sacked on the third play of Super Bowl 100, doctors looked at the readout from the EEG computer built into his helmet, and he remained in the game.

Over the years, the league’s increasingly complicated concussion protocol created frequent stoppages and mandatory substitutions, necessitating 90-person rosters, with five-man rotations at quarterback, akin to pitching staffs. This lazy-Susan approach—the QB carousel—was briefly relieved by cloning, a vogue that was abandoned as too costly. Teams eventually realized that creating a duplicate Tom Brady every bit as effective as the original required a duplicate Bill Belichick, an identical Gisele Bündchen and a doppelgänger Gronk.

When groundskeepers despaired of squeezing an unplayable Scrabble rack onto the field, Roman numerals went the way of the Roman empire.

Still, this rigorous scientific monitoring of the action ultimately allowed professional football to survive, and it changed the model of college athletics. The study of college players by university researchers allowed those athletes to be paid as research subjects, much in the same way that students are paid to participate in psychology experiments. Half a century ago—though it staggers the mind to think of it now—the top football-playing universities profited from the unpaid labor of what they euphemistically called “student-athletes.” But then the early 21st century was a more credulous age, when people would buy into “eight-minute abs” and “personal seat licenses.”

In fact, the biggest change in football over the last 50 years has been in the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of head injuries. “We’ll have a completely different way to diagnose [them],” Uzma Samadani, associate professor of neurosurgery at the University of Minnesota, predicted back in 2015, when she was a neurotrauma consultant to the NFL. “A concussion will be like a heart attack,” which is to say: more preventable, and urgently treated on the spot to limit damage.

So Harvard researchers developed an antibody to treat CTE. Today there are blood tests to detect certain proteins for early diagnosis, and helmets include concussion sensors to measure movement of the brain inside the skull. Still, the only thing science knows for certain is that football remains brutal and will never be made fully safe. Removing the Roman numerals did not exempt the Super Bowl from its echoes of gladiatorial Rome.

***

Barcelona brought its continental flair to the Super Bowl, running a variation of the Côte Ouest offense made popular in Paris in the 2030s, and took a 7–0 lead on a leaping catch by All-Pro receiver Lynnswann Davis, whose 60-inch vertical from a natural surface is among the best in the league and whose knees are among the highest rated by J.D. Power and Associates.

Fifty years ago Mounir Zok, senior sports technologist with the U.S. Olympic Committee, expressed hope that DNA would someday “resolve once and for all the big debate around whether talent is innate, or whether you can acquire it.” As it turns out, talent is baked into genes, whose variants affect the body’s ability to lay down collagen, which forms ligaments, allowing teams to predict which players are more susceptible to torn ACLs (if they have ACLs).

The Centurions quickly tied things up on a 32-yard touchdown dash by Anthony (Autonomous) Carr, who was running on the type of prosthetic legs—what we call “man-machine interfaces”—that have for years allowed amputees and the physically impaired to perform at the highest level in the NFL and other sports, all the while engendering the usual complaints about competitive advantage.

But every player has benefited from robotics and bionics. Fifty years ago Jason Kerestes, a robotics engineer at Boeing Research and Technology, asked, “Would we be practicing against robots and would we be honing our skills as humans by playing against a [being] superior to or a mimic of a human?” The answer, we now know, is a resounding yes. In the lead-up to this game, the offensive line protecting Barça quarterback João Montana practiced, as it has all season, against intelligent automatons—machines that are smarter and more athletic than tackling dummies and blocking sleds.

As time expired in the first half in Las Vegas, Centurions kicker Rae Gal made a 56-yard field goal to give the home team a 10–7 lead. While the presence of women in the NFL has long been recognized as a step forward, it also opened the league to cynical accusations that these new players had an unfair competitive advantage, as doping is more effective in female athletes. But even these accusations were human progress of a sort. Remember: NFL subterfuge used to involve taking the air out of footballs in bathroom stalls.

As the teams headed to their locker rooms, spectators didn’t file out to the nacho-printing stations. Everyone remained rooted to his or her spot for the halftime extravaganza, waiting for Elvis to enter the building.

***

Rock stars once looked to space for inspiration—the last century gave us “Rocket Man,” “Space Oddity” and “Intergalactic”—and took names that reflected our national obsession with interstellar travel: Ziggy Stardust, Freddie Mercury, Bill Haley and His Comets. Fifty-two years ago the Super Bowl halftime performer was a man named Peter Hernandez, who had taken the far-out stage name of Bruno Mars. Now that the Red Planet is colonized and space travel is no longer exotic, those names are quaint relics of retro futurism, those unrequited visions of the future that have long since faded into the past.

But as Earthlings endeavored to become multiplanetary, principally through the NASA and SpaceX Martian voyages in the 2030s, they proved that some of these visions do come to pass. And so virtual reality gave way to augmented reality: holograms appearing in our fields of vision, projected through eyeglasses. Thus, the Super Bowl 100 halftime show featured a chorus of holographic Vegas immortals in their prime (Elvis, Sinatra, Wayne Newton, Liberace) performing alongside today’s live Vegas icons (Britney Spears, North West and Blue Ivy Carter, not to mention the Greatest Rock and Roll Band in History, One Direction, now in its 56th year of touring). All this technology transformed sports and pornography until they are sometimes difficult to tell apart: two voyeuristic pursuits inviting spectators to join in.

There were two 20th-century geniuses known by their hooded sweatshirts, and both became synonymous with the Big Game: Belichick, for winning seven rings, and that early investor in augmented reality, Mark Zuckerberg, who posted on his Facebook page five decades ago: “Imagine enjoying a court side seat at a game ... just by putting on goggles in your home.”

When the augmented reality of halftime ended and the heightened reality of the second half returned, fans at home and in the stadium had a God’s-eye view of the action. With motion-capture sensors on every player, spectators had insight and angles into every movement on the field. When Carr, the Centurions’ back, coughed up the ball on his own two-yard line, everyone could place him or herself inside the ensuing scrum.

Human officials stood by their posts on the sidelines, also watching the game on implants, quickly spotting that Barcelona had gained possession. (It would score on the next play.) “Fifty years from now, I don’t know that we have human refs,” DuBravac had predicted in 2015. “If two eyes are good, imagine a robot with 60 image sensors.”

For decades, the NFL was about as international as an IHOP. Then came the London Beefeaters.

Indeed, the sensors built into every playing surface had turned human zebras into on-field obstacles. “We will put pressure sensors in every piece of padding, so you can determine statistically if his knee was down before his hand lost the ball,” DuBravac predicted, correctly as it turned out. In the same way, sensors in players’ shoes and on the sidelines showed, definitively, when a player had stepped out-of-bounds.

This precision, however, hasn’t eliminated second-guessing but increased it. Seeing every angle, including those to which players are not privy—hostage as they are to their own points of view—has given fans more information than the principals ever had. Perlin, an architect of this immersive technology, predicted even before Super Bowl 50 that the future would be a Golden Age of Second-Guessing, making 2016 seem like a gentler, less coarse era of human discourse, when talk radio and cable sports hot-take shows were comparatively genteel.

***

Barcelona drove, its receiving corps easily making the kind of receptions that were once called one-handed catches and are now known—thanks to the evolution of man and glove—as catches. The Catalans occasionally ran for small gains, paying lip service to the notion that running the ball is still necessary to keep defenses honest, though the increasing size on both sides of the line of scrimmage—tilting toward an average of four bills—has rendered the gaps ever narrower. This girth grew gradually, the way new layers of paint eventually seal a window shut.

Barcelona gained confidence with every five-yard snap. These snaps were once routinely taken under center, until passing became so prevalent that every formation was a so-called shotgun formation, or its truncated cousin, the pistol. NFL offenses finally settled on something in between. Mercifully, given the nation’s still uncontrolled epidemic of gun violence, we simply call it the snap.

The chain gang moved the down-and-distance markers, those cutesy reminders of the league’s humble analog origins, when three men carrying a 10-yard length of chain was deemed sophisticated-enough technology. Of course, the chain gang is merely ornamental now, like the Patriots’ minutemen mascots, because every millimeter of the field is electronically mapped and the ball is spotted accordingly. But the chain gang marches on anyway, a beloved anachronism. These officials are like the palace guards wearing bearskin hats in London, where the NFL first became truly worldly.

For decades the NFL spoke of being a global league, but was about as international as the International House of Pancakes (or less so, since IHOP had outlets in Canada, Mexico and the Middle East). But then came the London Beefeaters—changed to the Doubledeckers after vegans picketed—followed by Mexico City, Toronto, Frankfurt, Barcelona and on and on, the league bifurcating into two mega-conferences called the National Football League (comprising the old AFC and NFC) and the International Football League (everyone else), guaranteeing an international Super Bowl while also guaranteeing that one U.S. team would always play in it.

In Super Bowl 100 that team, the Centurions, took the ball on its own 20 with scarcely more than a minute left, down 14–10 following Barça’s second touchdown. After four quick completions against a porous prevent defense—some things never change—Las Vegas stared down four seconds on the clock, 21 yards to history.

Through his MindTalk device, Montana, the Centurions QB, listened to the affirmations of his team’s life coach. We’ve forgotten now, but these MindTalks were once used only to transmit play calls to a tiny receiver in the mouth guard, which carried the signal vibrations to the teeth, along the jawbone and into the inner ear, where QBs heard an inaudible “inner voice” that told them the play. Now, of course, every player wears such a mouth guard, and coaches transmit not just plays but also affirmations. Montana’s inner ear—channeling the voice of Centurions life coach O.G. Willikers in the press box—told him: “Relax. This is the fulfillment of your childhood dreams. You are about to throw the Super Bowl–winning touchdown.”

You know the rest. Las Vegas’s star receiver, Climbin’ Mike Simon, leaped for Montana’s arcing pass in the corner of the end zone. The springiness of the artificial turf subflooring, like a sprung floor for dancing, allowed him to bound six feet in the air, but it also softened his landing and protected his knees, at once increasing the safety and the spectacle of professional football. Simon reached up with both hands—it’s the two-handed catch that now requires a modifier—and clapped his left palm over the ball in his right, as if slapping a rebound in basketball.

When he came down with the ball, and the ref-bot glowed green to signal the touchdown, pulse rates spiked worldwide. The fans in attendance who had opted to wear biosensors that measured their vital signs—blood oxygen levels and perfusion indices—set a new Super Bowl record for Visceral Reaction Measurement. (Think of it as a kind of decibel level of human emotion.)

Years ago there would have been a replay on a large in-stadium screen called a jumbotron, a name that sounds camp and retro-futuristic to our modern ears. Now, of course, the play was replayed, from an infinity of angles, in our own fields of vision. Barcelona challenged the call, unsuccessfully, claiming that the Centurions had stolen the bio signs of coach Pep Olaguardi by using emotion-reading software to read the mind of the Catalans’ defensive coordinator. “Technology in some regards actually enables people to cheat in new ways that are difficult for us to anticipate,” noted Maurice Schweitzer, professor of Operations, Information and Decisions at the Wharton School, way back in 2015. He now looks like Nostradamus.

The company that developed this software a half-century ago, Affectiva, had 3.2 million faces in its data-base and could read countless human expressions (though decades ago the technology proved ineffective on Belichick, who had only one expression and possibly only one emotion). But this sort of timeless espionage is the reason some coaches still cover their mouths with laminated play cards that look like Waffle House menus when they speak. (Indeed, this is the only use left for play cards.) It is also why every coach wears a poker face on the sideline, as Bud Grant did nearly 100 years ago.

The play card is not the only charming anachronism that remains. Traditions are still important. And so, by ancient custom, the Centurions accepted the Vince Lombardi Trophy from the commissioner, Chip Goodell, and then—this being Super Bowl 100—were congratulated in person, on the field, by the 51st U.S. Commander in Chief, President Robert Gronkowski.

The Super Bowl MVP was once voted on by a panel of men and women from the media, who wore their lanyards like a scholar’s hood. But now, of course, there is a precise mathematical formula—a rigorous set of analytics—that makes the call foolproof. As MVP, Montana took the keys to his new car from a Google vice president who marveled into the microphone that once upon a time, in a long-vanished era of innocence before autonomous vehicles, football players—even Hall of Famers such as Tom Brady and Peyton Manning—were forced to drive their own cars and pump them full of gas. They might as well have given those men horses, or unicycles. The cars now drive us, as God intended, their energy replenished overnight, and no one raps about tight whips or sings about driving Chevys to levees.

But some eternal verities remain. A blimp, filled with gas and named for a tire manufacturer, still floated above the title-game festivities, for no other reason than: We like it like that. For all the benefits of our latest wearables and ingestibles, we still love our dirigibles. The football field still goes to 100, and now, so does the Super Bowl.

It would be foolish to imagine what Super Bowl 150 might look like—who could possibly forecast 50 years down the road?—though it is always in our nature to wonder. In some ways, the future is a kind of eternal utopia, full of promises forever out of reach. In Las Vegas, as confetti cannons discharged their ammo into the desert night, the MVP turned to the NFL’s own cameras and said, “I’m going to Disney World,” where there remains an attraction that fascinates every generation and always will. It’s called Tomorrowland.