Inside exclusive club of coaches who led two different teams to Super Bowl

As part of our countdown to Super Bowl 50, SI.com is rolling out a series focusing on the overlooked, forgotten or just plain strange history of football’s biggest game. From commercials to Super Bowl parties, we'll cover it all, with new stories published frequently here.

When Dick Vermeil led his scrappy 1980 Philadelphia Eagles to Super Bowl XV in New Orleans, capping a long and arduous five-year climb to the top of the heap in the NFC, he never really felt at ease on the game’s grandest stage. His team had definitely earned its place in the biggest game in pro football, but deep down he didn’t know if he was truly qualified for the NFL’s loftiest coaching assignment, where the stakes are at their highest and the spotlight its brightest.

“The first time I went [to the Super Bowl], I wasn’t really sure I belonged there,” Vermeil said recently. “Here’s a former high school football coach, a junior college coach, and now he’s in the NFL and coaching against people the status of Tom Landry, Don Shula, Chuck Noll, Don Coryell, George Allen, Hall of Fame coaches. All of a sudden you find yourself across the field from them, and I really think one reason I pushed myself so hard back then is I was insecure in that environment with them. I wasn’t sure I belonged in that company.”

Inspired by his late father, John Parry officiated Super Bowl XLVI perfectly

Remarkably enough, 19 years later, Vermeil went back to the big game. After forsaking a successful and secure broadcasting career to return to the rigors of NFL coaching, he took the prolific 1999 St. Louis Rams to Super Bowl XXXIV in Atlanta, where his experience and outlook were entirely different. Not only did his Rams win a ring in one of the most thrilling finishes in Super Bowl history—in juxtaposition with his Eagles, who came up short and lost by 17 points to Oakland—Vermeil’s vantage point was dramatically altered by the wide gulf of time between his two Super Bowl appearances.

“There’s no question, I was seeing that game and that experience from a better perspective with the Rams,” he said. “I was feeling, ‘Hey, I belong here.’ I had done it once, built a team, and I thought I knew how to do it again. And with a lot of help, we were able to get it done. But I did it a different way. I didn’t coordinate my own offense. I didn’t call my own plays. I didn’t coach my own quarterback. I did a better job of delegating and leading and trying to develop an environment in which people could really excel in, and there we were, world champions.

“But the thing I realized at that point is winning doesn’t change you as a coach. It changes how people look at you. I had coached in a Super Bowl before, and probably did a better job to get there and lose in five years with the Eagles than I did to get there and win in three years with the Rams. But as soon as you win that game, people look at you differently. I’m always introduced now as a Super Bowl-winning coach. Trust me, you don’t get as much of a label or a fancy intro when you lose it.”

But there is another label Vermeil proudly wears and another club he belongs to that’s even more exclusive than the fraternity of Super Bowl winning coaches: He’s one of just six men to have taken two different teams to the Super Bowl, accomplishing the difficult task of re-climbing that particular mountain with an entirely new cast of characters.

The lineup of headline names who have that distinctive bullet point on their resume reads like the who’s who you’d expect, with some of the most successful coaching careers of the league’s past 50 years represented: Don Shula, who went to six Super Bowls with Baltimore and Miami; Bill Parcells, who went to three with the Giants and New England; Dan Reeves, who went to four with Denver and Atlanta; Vermeil, who went once each with Philadelphia and St. Louis; Mike Holmgren, who went to three with Green Bay and Seattle; and John Fox, who went once each with Carolina and Denver.

Jackie Smith talks extensively about the drop that almost ruined his life

All of them doubled down on their Super Bowl legacies at some point during their illustrious careers, experiencing the game from a different perspective than their initial trip or trips. And while a coach still has never won the Super Bowl with two separate teams—Hall of Fame Jets/Colts coach Weeb Ewbank is the only man to win both a pre-Super Bowl era NFL title with one team and a Super Bowl with another—these six are in a class by themselves.

In interviews conducted with all six coaches last summer and fall, here are their stories.

DON SHULA: The Forerunner

The game is all about winning. If you get there and don’t win, that’s something that sticks, and people always like to remind you of things like that.

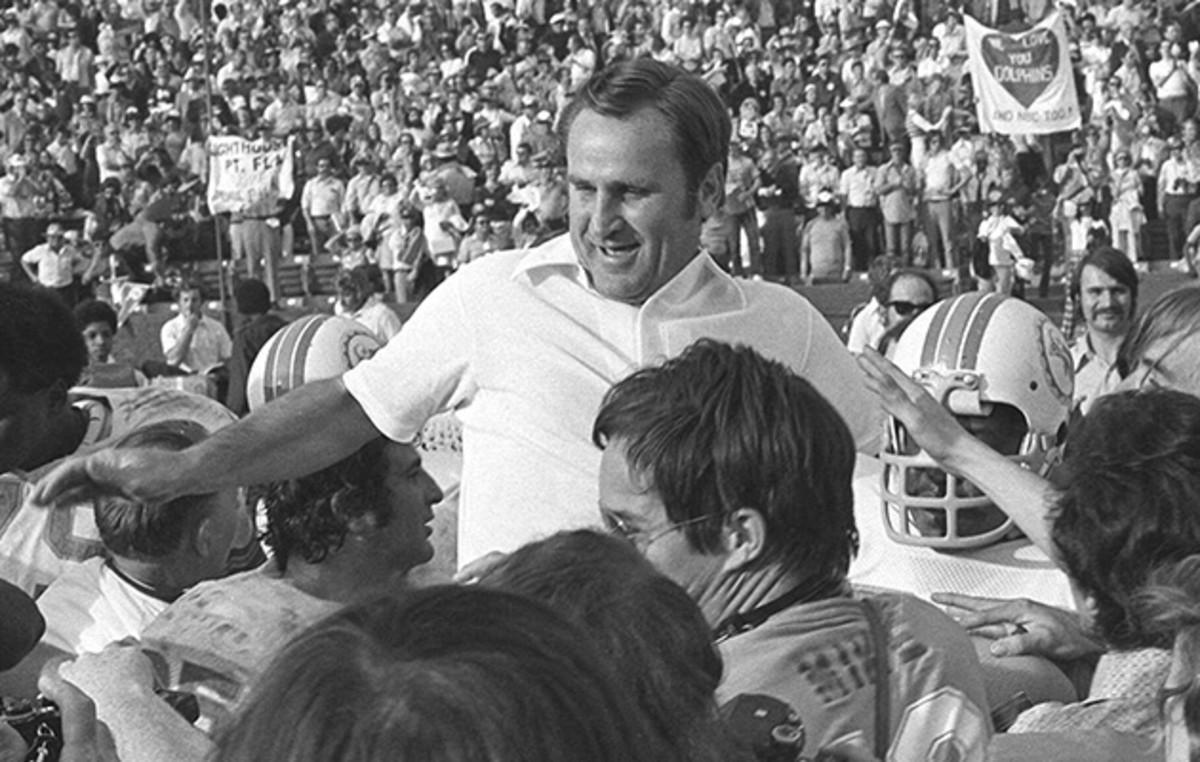

Naturally the history-making Don Shula was the first coach in the club. His heavily favored 1968 Baltimore Colts fell victim to the upset of the ages against Joe Namath and the New York Jets in Super Bowl III, and then Shula returned to the Super Bowl five more times with his Miami Dolphins, making the first of three consecutive trips after the 1971 season. On a mid-summer day in late July at his spacious waterfront Miami area home, Shula, 86, is both expansive and philosophical when it comes to discussing those divergent early Super Bowl experiences, when he lost twice and won twice in the first eight years of the Super Bowl era.

No memory in his long Hall of Fame coaching career still stings as much as the Jets‘ iconic conquest of his Colts, but just three years later his Miami club made the game, and the following season the 17–0 Dolphins of perfect season fame stood at the pinnacle of the game and alone in the record books.

But first came the stunning 16–7 loss to the AFL’s Jets, when Namath backed up his brash guarantee with the win that finally put the American Football League on a level playing field with the older, more established NFL.

Super Bowl injuries: What it’s like to get hurt in the game of your life

“The thing that people don’t realize is the Jets were pretty good, and Joe Namath was pretty good,” Shula said. “And he boldly made the prediction that they were going to win the game, then they won the game. But Joe Namath had been the Jets quarterback for four years and we had Earl Morrall, who was our quarterback that year, for four months. Namath just had a big day, the Jets had a big day, their coach (Ewbank) had a big day and we didn’t.

“It’s not a bitter memory. It’s just a bad memory. I don’t get up thinking about it every day, or letting it bother me or ruin my life. But it’s there and I’ve got to acknowledge it, and I’ve got to live with it.”

Time and perspective have done their work, but 47 years later Shula can still feel Super Bowl III if you’re brazen enough to pick at the scab. It’s never going to completely heal.

“Super Bowl III was just such a disappointment, being so heavily favored and seemingly everything was pointed in our direction, and then to fail,” Shula said. “And that failure kept getting brought up and it wouldn’t go away. There were a lot of New York people that really enjoyed that. So I had to learn to live with it and I couldn’t do anything about it until we did something about it. And the only way you can do something about it was when you had the opportunity to win the next time.”

Shula’s Dolphins didn’t win in his next Super Bowl opportunity, falling 24–3 to Dallas in Super Bowl VI in New Orleans, but then came Miami’s back-to-back crowns, and a 32–2 record over the span of 1972-73. Vindication was Shula’s. First he and his Colts were on the wrong side of history, then he and his Dolphins made history.

“Yeah, I enjoyed the last part of that a little more, making history in an unprecedented way. Because when you think about doing something that no team had ever done, that’s pretty important, pretty satisfying.”

In hindsight it seems hard to believe, but Shula’s early-career Super Bowl failures labeled him as a loser, even though he wound up being the only coach to ever lead a team to that game in three different decades—the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s.

“It was very meaningful to me to be knocking on the door almost every year,” Shula said. “That’s why you’re in the coaching business. You want to take your team to the big game, and you want to not only take them there, you want to win the big game. The game is all about winning. If you get there and don’t win, that’s something that sticks, and people always like to remind you of things like that. There were things said about me that I really resented: ‘He’s a good coach, but he couldn’t win the big one.’ Anytime they say that, that’s something you don’t want to hear and don’t want to be associated with. But it doesn’t go away until you finally win the big one.”

BILL PARCELLS: The Mover

But with most of us, when you win one, nothing else really satisfies you any more. So it can be a curse as well.

Unlike Shula, who lasted a Methuselah-like 26 years on the Dolphins sideline, Bill Parcells’s peripatetic NFL career was largely spent tackling a series of new challenges. With some gaps in between, as a head coach he jumped from the Giants to the Patriots to the Jets to the Cowboys, taking on a succession of rebuilding projects because, well, that’s the kind of challenge that gets him out of bed in the morning.

After winning the first two Super Bowl titles in the history of the New York Giants franchise, in 1986 and 1990, Parcells stepped away from the game for two years due to health reasons, undergoing cardiac bypass surgery. When he returned to the league in 1993, he agreed to coach the floundering New England Patriots, who were coming off a dismal 2–14 season in ’92. In his fourth and final year in Foxboro, the Patriots made Super Bowl XXXI, losing to Green Bay 35–21 in New Orleans. But that four-year climb wasn’t always a steady ascent and Parcells was attempting a return to dominance that no other two-time Super Bowl-winning coach had ever accomplished.

“It invigorated me, the challenge of trying to get a team back to a competitive level,” said Parcells by phone this fall. “I was coming off the bypass surgery operation, so I was feeling better than I had been. Mentally I was ready to get back to coaching. And what you’re trying to do, you’re trying to get to the top of your profession, to the top of your industry. Even if it’s momentarily. And winning a Super Bowl gets you there.

“It’s a very gratifying thing in some respects. But with most of us, when you win one, nothing else really satisfies you any more. So it can be a curse as well. Because the aspirations change, and you’re going from trying to be competitive and getting into the playoffs, to where it’s now, ‘Well, if we don’t win the whole thing we’re not successful.’ That’s what happens.”

How the Janet Jackson halftime show aftermath changed the Super Bowl

In New England, Parcells’s rebuild was aided by owning the first overall pick in the 1993 draft, a selection the Patriots used on Washington State quarterback Drew Bledsoe, who four seasons later started in the Super Bowl against Green Bay. Parcells also added via the draft talents such as Terry Glenn, Tedy Bruschi, Ted Johnson, Adam Vinatieri, Ty Law, Lawyer Milloy, Chris Slade and Willie McGinest, helping lay the foundation for the Patriots’ dynastic era to come.

“You’re not even thinking about a Super Bowl when I’m in my first year there,” Parcells said. “I mean, I’m just trying to win a game. We’re 1–11 at one point, then we won three or four games in a row at the end of the season. And that helped us going into next year. But it was no steady ascension. It took time to get enough guys and to get the guys that were young enough experience to compete on a high level.”

Having twice experienced the post-game joy ride of being the winning Super Bowl coach with the Giants, Parcells lost with the Patriots and got to see the steep downside of the NFL’s final game. After being celebrated as champions for two full weeks coming out of the conference title game, the Super Bowl loser almost ceases to exists once the confetti drops. Those who have done both almost uniformly say the agony of losing that game well exceeds the ecstasy of winning it.

“I agree with that,” Parcell said. “I can still just vividly see, it’s late in the game, we’ve scored a touchdown to make it 28–21 and we’ve got a lot of momentum. And then Desmond Howard ran the kickoff back for a touchdown and that kind of finished us. Losing that game, it’s very disconcerting. You feel a little bit like a failure, and you feel a little bit like you didn’t accomplish all that you could. And you don’t ever know if you’ll have another chance to do it. That’s the thing that kind of weighs on you a little bit. You put a whole year’s work in and it’s gone.

The man behind the legend: McGee’s story goes well beyond SB hangover

“You’re a month past the game and you’re riding in your car and you’re still thinking about what you could have done differently, you know what I mean? It stays with you. You live with that. That’s one of the lonely times in pro football.”

Parcells, in his quest to “pick the groceries” for the team he coached—his euphemism for having complete personnel authority—left the Patriots after the Super Bowl loss to take over the reins for the rival New York Jets. It was that rumored move that turned into a juicy Super Bowl sub-plot and potential distraction in New Orleans, and Parcells recalls the week as “not without a little turmoil.” But just two years later, he came as close as any coach ever to leading a record third different team to the Super Bowl, with New York losing the 1998 AFC Championship Game 23—10 at Denver, after leading at halftime.

“Probably the most disappointing loss I ever had was in Denver with the Jets,” Parcells said. “Because (Jets owner Leon Hess) Mr. Hess was getting older and he had been 100 percent supportive of us. We had the lead, and then we just made some mistakes in that game, and they came back and beat us. It was so disappointing because I was really kind of hopeful for Mr. Hess that we could do that.”

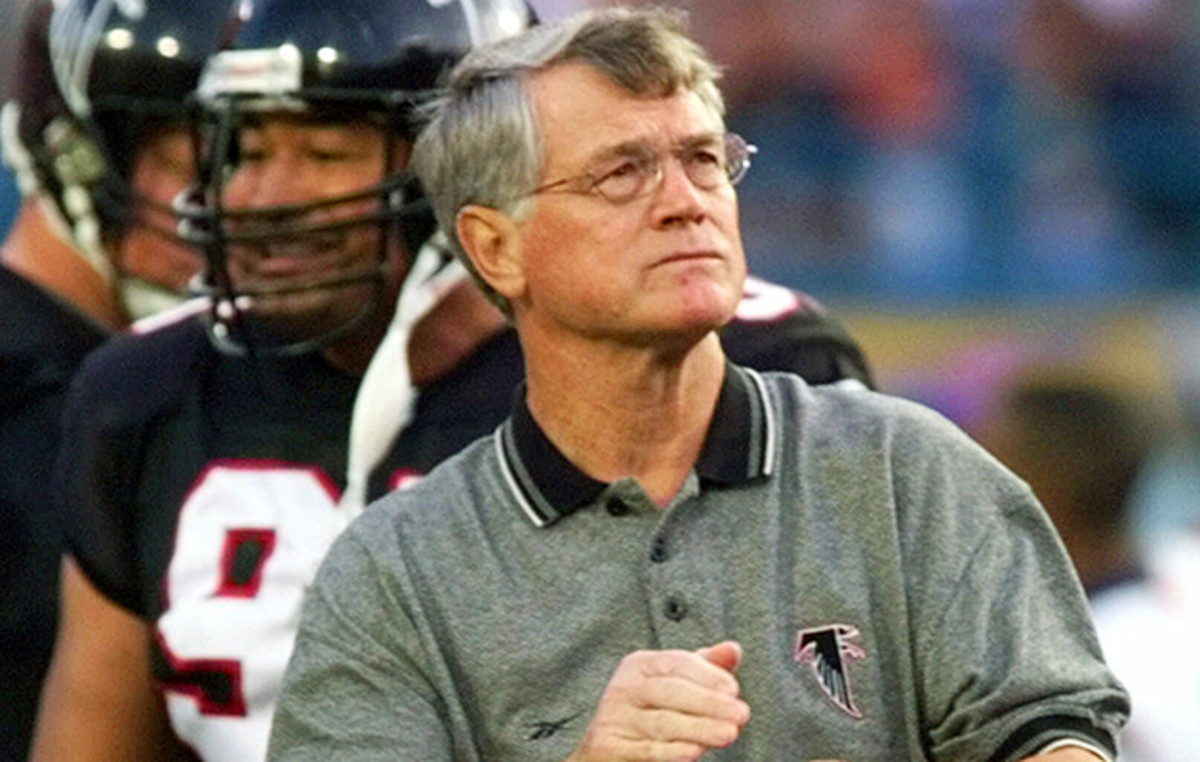

DAN REEVES: The Super Bowl Mainstay

The number is so astounding it almost sounds as if it can’t be right. But it is. In a span of 29 NFL seasons from 1970 to 1998, Dan Reeves was a player or coach on nine Super Bowl teams—which is almost one trip every three years. He went twice as a Cowboys running back (1970–71), three times as a Dallas assistant coach (1975, ’77, ’78), three times as Denver’s head coach (1986, ’87, ’89) and once as Atlanta’s head coach (1998).

That’s more Super Bowls than anyone in the history of the NFL has taken part in, with New England’s Bill Belichick just behind Reeves at eight, the first two coming as a Giants assistant coach under Parcells. Yet when you talk to the humble Reeves about his Super Bowl experiences, that mind-boggling distinction doesn’t even come up in conversation until the interview is almost over. Reeves was on hand for eight of the 20 Super Bowls from 1970–89, making it seem almost as if the league was not allowed to hold the game without him.

“I know when people introduce me they say that, that I’ve been to more Super Bowls than anyone else,” Reeves said by phone. “I’ve never looked it up or even asked anyone. I know Belichick’s got to be close. And he’s won a bunch of them.”

Alas, that is the rub with Reeves’ track record in the eyes of some. He’s just 2–7 on Super Bowl Sunday, earning a ring as a player with the 1971 Cowboys, and another as a Dallas assistant in 1977. He lost once as a player, twice as an assistant, and four times as a head coach, with Denver going 0–3 and Atlanta 0–1. But imagine the feat of losing more Super Bowls (seven) than anyone would have the right to even dream of winning their way to.

After his 12-year tenure as Denver’s head coach ended after the 1992 season, Reeves spent four years coaching the New York Giants and then took over the perennially troubled Atlanta Falcons in 1997. He joined the two-team-Super Bowl coaching club in 1998, when his Falcons put together a magical 14–2 regular-season, then pulled off one of the biggest upsets in NFL playoff history, knocking off the record-breaking 15–1 Minnesota Vikings on the road in overtime in the NFC Championship Game.

A native of Rome, Ga., Reeves’s unexpected Super Bowl season—the first and still only in Falcons history—was sweet. He had overcome quadruple bypass heart surgery in December that cost him three games on the sideline, and getting back to the NFL’s big stage one last time offered a fitting career-capping achievement in his fourth decade in the league.

“Really and truly I think just getting there period is difficult,” Reeves said. “And certainly when you come to a new organization, you look at it and say, ‘This is what I’d like to do. I’d like to get us into the playoffs.’ And once you get in the playoffs, you have a chance. That was our focus when I came to Atlanta in ’97, and we really started playing well at the end of that year, so going into the ’98 season we had a lot of confidence, which really helps.”

Reeves’s Falcons beat the 49ers, the reigning beast of the NFC West, and the Vikings in the playoffs, then as fate would have it, lost 34–19 to his former team, the Broncos, in Super Bowl XXXIII in Miami. Though Reeves could never quite push that rock to the very top of the mountain as a head coach, enduring four blowout defeats in the Super Bowl, his longevity and ability to repeatedly put his teams into position to play for the championship is a remarkable accomplishment of itself.

The Disappearing Man: The Raider who went missing before Super Bowl

“Heck yeah, to be in that group is really something special,” said Reeves, of the coaches who have taken multiple teams to the Super Bowl. “You’d like for it be all with one organization, like a Coach (Tom) Landry or Chuck Noll. But it didn’t work out that way and I was fortunate enough to have to two other jobs after I got fired in Denver. To be able to get to the Super Bowl with Atlanta, it was just a tremendous accomplishment for the organization.

“They were just dying. It was an expansion team that had knocked on the door several times, but was never able to get there before. So to win that NFC Championship Game the way we won it in Minnesota, it was just unbelievable. And of course being from Georgia and having grown up here, it was just special. It really was.”

DICK VERMEIL: The Comeback Coach

The only way to know how it feels is to have one to compare it to another, and winning is much better, I know that.

No one in league history has turned the trick Dick Vermeil did, making Super Bowl trips 19 years apart. The next longest span is the 16 years that bridged Don Shula’s first Super Bowl, with the 1968 Baltimore Colts, and his final of five Super Bowls as Miami’s head coach, after the 1984 season. And those were the only Super Bowls of Vermeil’s coaching career, giving him an unique perspective of the game, separated by nearly two decades.

“I think it’s tougher to get there twice with two teams, than it is even to win it once, because you have to re-invent yourself,” said Vermeil, who was 44 when he took his Eagles to the game in January 1981, and 63 when he made it back with the Rams in early 2000, after being out of the NFL for 15 of those years in between. “I know my second time in that game, I was more mature as a head coach and a leader. I don’t think I was quite as overwhelmed by the overall experience of going to a Super Bowl. I’d been there and lost. And then what I also realized is it takes the same thing to go there and lose as it does to go there and win.”

Vermeil’s Rams went to the Super Bowl in just his third season back in the league, two years longer than the painstaking journey his Eagles traveled. But he makes little distinction between his two best clubs, except for the obvious one.

“The only way to know how it feels is to have one to compare it to another, and winning is much better, I know that,” said Vermeil, one of the four coaches on our list who has both won and lost a Super Bowl. “But I have every bit as much respect for my Eagles team that lost as I do the Rams team that won. You realize you’ve got to be at your best game day, and you’ve got to be at your best health-wise. And we weren’t either way with the Eagles.

“My advice is just don’t get there and go minus-3 in turnovers. And go with all three of your starting receivers healthy. We had one of them healthy. You’ve got to be perfect that day and we were not perfect.”

Thirty-five years after his Philadelphia club went to the first Super Bowl in franchise history, Vermeil sees no mystery in why the Eagles lost by three scores that day. So it’s still a point of bemusement to him that the narrative that arose to explain Philadelphia’s blowout loss to the Raiders was that his pre-Super Bowl practices and regimens were too intense, while Oakland’s players were looser and more relaxed.

“Regardless of how you lose the game, whether it’s factual or manufactured, there will be many people who will draw a conclusion,” Vermeil said. “The conclusion we heard was I was too strict with them, worked them too hard and they were wound up too tight. The same reason we beat the Dallas Cowboys in the NFC Championship Game now became the reason we lost two weeks later.”

The Rams’ Super Bowl victory over Tennessee in Atlanta was vindicating for Vermeil, and he re-retired from coaching shortly after the game. St. Louis boasted an embarrassment of riches when it came to offensive talent, with quarterback Kurt Warner’s surprise emergence that season being the missing piece to go with the likes of running back Marshall Faulk, receivers Isaac Bruce and Torry Holt, and tackle Orlando Pace.

But in both the case of the Eagles and Rams, Vermeil’s fixation is on where those clubs came from, rather than where they ended up. The hard work that went into the building of those rosters means as much to him as where they finished.

“I’ll tell you what I’m most proud of, because I did the study, those two teams went to the Super Bowl despite losing almost 70 percent of their games in the seven years prior to us taking over the program,” Vermeil said. “Both of them had more losses in the seven years before than any other team in the football. When I took over the Eagles in 1976, the seven years prior they’d won 31 or 32 percent of their games. When we took over the Rams in 1997, they had lost about the same, with one more loss than the Jets during that span. There’s only four or five of us coaches who can say that and I’m proud of it.”

MIKE HOLMGREN: The Builder

I still live in Seattle and ever so often somebody will come up and say, ‘Thanks for building it. Thanks for getting it started.’ And that’s important to me. I feel good about that work.

People still walk up to Mike Holmgren and want to know what he was thinking, leaving Green Bay in early 1999, after just seven years on the job as Packers head coach. After all, at the time he had the game’s best quarterback in Brett Favre on his roster, and No. 4 was still in his prime. He had won one Super Bowl ring in Green Bay, led the Packers to back-to-back Super Bowl appearances, worked with one of the game’s premier general managers in Ron Wolf, and even had a street named in his honor in Titletown. What was out there in Seattle that could top that?

“People ask sometimes, ‘Are you sorry you left Green Bay?’ It still comes up,” said Holmgren, with his trademark soft chuckle. “On the surface in the coaching business, people say it wasn’t the smartest thing I’ve ever done. ‘You had a brilliant young quarterback and a great place to work. What in the world?’”

While the “what” is difficult to explain, especially to Packers fans in the late ‘90s, it’s also what has always driven Holmgren. The need to re-invent, and to re-create. It was one of the primary impetuses for his then-stunning move to Seattle, where he took complete control of the Seahawks football operations.

“In my DNA, there’s a certain wiring that I have in common with some other coaches,” Holmgren said. “One of the things that was important to me was taking something and building it up. Maybe not having all the pieces in the beginning, but then you take on the challenge of building it up. For whatever reason, that was the way it worked for me.

“It was about going to Seattle, and getting Matt Hasselbeck in there, and being able to take a quarterback—and they come in various sizes and ability—and teach him how to play quarterback, how to really play the position. Then you hand him the ball and off he goes. He does what he has to do. I feel good about that. I think we did a nice job of teaching guys how to play the quarterback position.”

When college all-stars faced off against reigning Super Bowl champs

Holmgren’s 1996 Packers won Super Bowl XXXI in his fifth season on the job (against Parcells's Pats), and the next season were heavily favored to make it two rings in a row, but were upset 31–24 by Denver, a loss that admittedly haunted Holmgren far longer than the sheen of the previous year’s success stayed with him. He lived the highs and lows of a Super Bowl coach in a very compressed two-year period. You win some, you lose some, but the losses hurt worse than the wins feel good.

“When we lost in (the) 1997 (season) to Denver, that one stuck with me for a while to the point where I was a little screwed up for a month or two,” Holmgren said. “I mean I couldn’t sleep, my appetite was down—and I’m a big man, I like my food—I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t do anything. I finally told my daughter, who’s a doctor, she said ‘What’s the matter?’ I said ‘I don’t know. I’m goofed up.’

“And she goes, ‘Have you looked at the film of the game?’ And I said, ‘No, I don’t want to.’ And she said ‘You’ve got to look at the film,’ so I did, and it kind of snapped me out of it. She said ‘You’re depressed. You’re kind of depressed. It’s a clinical thing.’ But shoot, it’s hard. I felt like we had the more talented team in Green Bay when we lost to Denver, but I could not for the life of me get them to believe the Broncos were as good as they were, because they were a wild-card team. I have a whole new life now, but when somebody will bring that game up, it’s kind of like a knife going through the ribs. But that’s kind of how coaches are.”

It took him seven seasons of incremental progress to get the job done, but Holmgren led his Seahawks to the first Super Bowl in franchise history in 2005, a game they lost 21–10 to Pittsburgh, which came out of the AFC as a red-hot sixth seed. That loss stung, but he realized a certain sense of satisfaction in getting Seattle to the dance, and making it relevant at a level it had never before risen to. With apologies to Vince Lombardi, another former Packers head coach, winning isn’t everything, or the only thing, Holmgren came to believe.

“I remember hearing players or coaches talk about the Super Bowl, if we don’t win the game, then the season is not worth anything,” Holmgren said. “I said, ‘Baloney.’ If you say that, you’re discounting six, seven, eight months of your life that didn’t count. It’s about pushing that rock up the hill. Getting through the tough stuff, and the feeling of a team coming together and then eventually getting to the final game. I’m not ever going to discount that journey, just because when you play the game somebody has to win and somebody has to lose. There have been guys like Chuck Noll and Bill Walsh that never lost one, but shoot, just getting there, you can be really proud of your team and I was.”

The Seahawks finally reached the NFL’s mountaintop in the 2013 season, winning the Super Bowl two years ago under head coach Pete Carroll, and returning to the game last season as well, when they lost in devastating fashion to New England.

Holmgren feels a certain sense of table-setting pride in the organization Seattle has become, with its perennial winner status. His work helped get that ball rolling.

“I still live in Seattle, and that team is rolling and they’re way good,” he said. “They won the Super Bowl, something we didn’t get done, and I’m happy for Pete and for the team. But ever so often somebody will come up and say, ‘Thanks for building it. Thanks for getting it started.’ And that’s important to me. I feel good about that work.’’

JOHN FOX: The Adapter

Always a quick study, John Fox reached the Super Bowl in his second season as Carolina’s head coach in 2003. He went back to the biggest of games in his third season with Denver, in 2013. And I guess that bodes pretty well for the 2018 Bears, which would be Fox’s fourth season in Chicago. Unless he sticks with the every 10 years trend and leads some unspecified team to the Super Bowl in 2023. As the only active coach in this exclusive six-man club, all possibilities remain open.

“It takes a special group to even get to one,” Fox said, late in his first season as the Bears head coach in 2015, after his wildly successful four-year coaching stint in Denver, where he led the Broncos to four consecutive AFC West crowns and the 2013 AFC title. “I really think it’s special just getting to that game, given the amount of work that goes into it. It’s kind of what motivates me here in Chicago now. It’s about putting together a culture, with the right personalities of people. And I’m talking about everyone, coaches, players, trainers, equipment guys, there’s just so much to it. It’s about getting a great group of people to commit to a mission and then executing it. Then to be able to do that twice, in two different places, really that’s what motivates me today, to try and do it a third time here in Chicago.”

Part of Fox’s ongoing drive to return to the Super Bowl stage is obvious, in that his Panthers lost narrowly in the final seconds to New England in Super Bowl XXXVIII, with his Broncos a decade later being blown out 43–8 by Seattle two years ago. As a defensive coordinator with the New York Giants in 2000, Fox’s first Super Bowl experience was also a losing one, with Baltimore routing the Giants 34–7 in Tampa. That 0-for-3 record never completely leaves his mind, but it does not define him.

“You take pride you in any time you get the opportunity to go to that game,” Fox said. “I remember my first chance was with the New York Giants in 2000, as defensive coordinator, and I had coached for quite a long time at that point, because I started in the NFL in 1989. So that’s a lot of years and I had never been to one.

The SI story that wasn't: Covering Super Bowl XXIX with the Hobo King

“After we lost to New England with Carolina, I was talking to (longtime NFL assistant coach) Howard Mudd one day, and I said, ‘Gosh, this is the second one I’ve been to and lost.’ He said, ‘Foxy, I’ve been coaching for 30 years and never been to one.’ So you don’t realize how hard it is in a career to get to even one. It’s a huge, huge privilege. At the end of the day, it’s a lot of people working really hard to accomplish something big. Unfortunately I’ve never won one. But it’s not easy to get to and obviously not easy to win them.”

Fox took over a Carolina team in 2002 that a year before had hit rock bottom at 1–15 under coach George Seifert. By 2003, the Panthers were 11–5 and upset top-seeded Philadelphia on the road in the NFC Championship Game, earning a trip to Super Bowl XXXVIII in Houston. It was a Cinderella story that ended just shy of ultimate glory, but the Panthers making the franchise’s first Super Bowl with the undrafted Jake Delhomme was a remarkable feat in and of itself. Then again, it perhaps wasn’t even Fox’s best coaching job, given that his first Broncos team won the AFC West in 2011 with Tim Tebow at quarterback. One of Fox’s strengths is his ability to adapt and succeed with the talent on hand.

When Fox returned to the Super Bowl after the 2013 season, with Denver, future Hall of Famer Peyton Manning was his quarterback. Not that he made much of a difference in the galling 35-point loss to the Seahawks.

The Super Bowl that tore a family apart, forever changed stadium deals

“Really our best team in Denver was that 13–3 team in the 2012 season,” Fox said. “That’s the one I thought should have gotten there. That’s the year we lost at home to Baltimore in overtime (in the divisional round), and they went on to win it. Then we got there in ’13 and got beat to crap. It’s just weird how it all works. It doesn’t all work perfectly like you’d hope.

“The Super Bowl in New York, that one started bad and got worse. But we did beat New England in the AFC Championship Game and there still a lot of positives, even though we ended up on that losing note.”

Like Holmgren, Fox said he derives his greatest satisfaction in coaching from the assembly process. Building a team, a culture and an environment where players can prosper and thrive, coming together to see how much they can accomplish. His Bears are just beginning year two of that process.

“That is my motivation,” Fox said. “It’s not winning it as much as it is just putting it together. Just getting the right kind of people all rowing in the same direction, arm and arm, all the stuff it takes to be a good team. And then to weather a whole regular season and playoff season to get that opportunity in the Super Bowl. Hopefully some day I’ll get the chance to win it.“