The Birth of a Dynasty and the Death of a Dome

For the next two weeks The MMQB will be on the road to Super Bowl 50, telling stories of the game’s history and the Panthers-Broncos matchup, meeting notable Super Bowl figures and exploring what the game means to America, from coast to coast. Follow the journey on Twitter and Instagram (#SB50RoadTrip) and read the series. And if you see us on the road, give a wave.

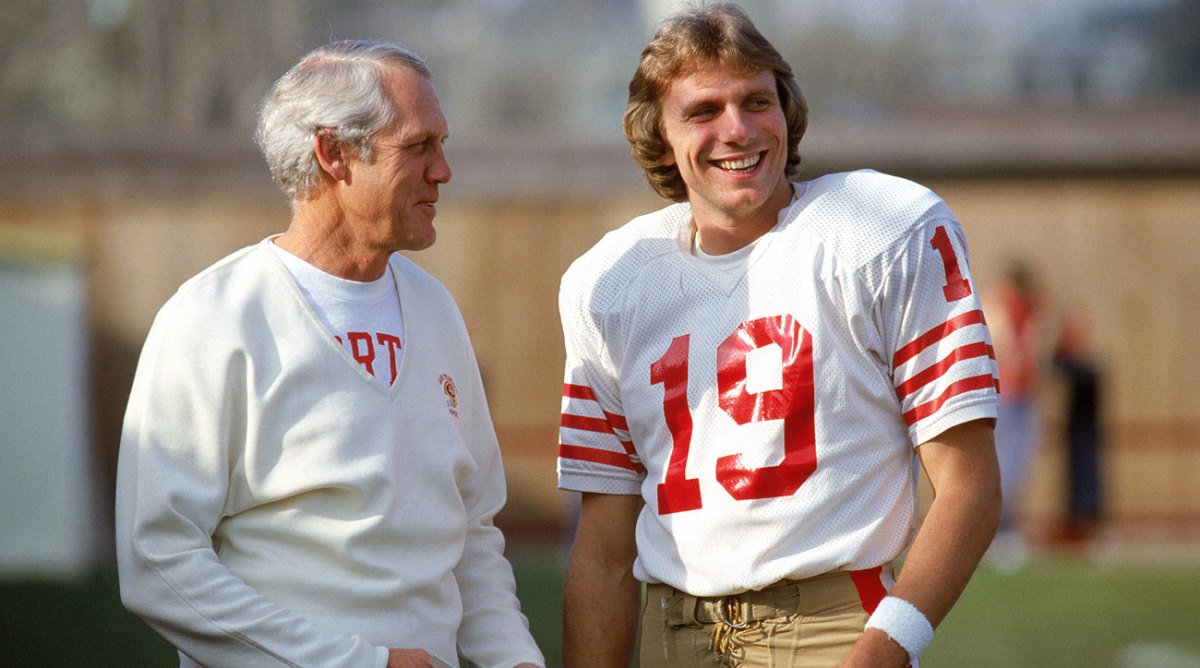

PONTIAC, Mich. — On a bitter cold January day in 1982, a bus carrying Bill Walsh, Joe Montana, and half of the San Francisco 49ers pulled off Highway 59 and onto a 127-acre lot a half-hour’s drive from Detroit. This corner of Featherstone and Opdyke Roads was the home of the Silverdome, then just six years old, and with its inflatable roof, considered to be at the forefront of indoor-stadium design. It had been nearly three years since Pontiac had been awarded the Super Bowl, a coup for northern cities trying to wrestle the game away from the South’s hold. “It’s been a long road,” NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle said at the announcement. “Several years ago, people of Pontiac talked to me about a domed stadium. They got one, and you people did a great job presenting your case for the Super Bowl.”

Thirty-four years later, that famed roof lies in tatters inside the stadium’s remains. The seats where so many watched Barry Sanders do eight magic shows a year are now vulnerable to the merciless Michigan elements. Outside, the lot is mostly deserted. The northeast corner is home to spillover parking for a nearby Chrysler office, with an indoor practice bubble used for youth soccer about 100 yards away. But most of what remains sits in decay. Real estate brokerage signs—“Land Available–Divisible”—dot the brown grass. “No Trespassing” signs line the fences. An early ’90s maroon Suburban stands guard to shoo away anyone wanting to take in the piles of twisted metal, rolled-up turf and rotting forklifts that sit beneath the drive-in movie screens installed after the Lions bolted for Detroit.

“There’s an $80 million stadium that was sold for $560,000 that’s sitting in waste and looks like a war zone,” says Ron McVety, the nephew of original Silverdome designer C. Don Davidson.

The Silverdome has only a few months to live. Demolition is scheduled for this spring after its new owners—who actually ended up paying $583,000 including real estate fees—decided it couldn’t be salvaged. Locals are pleased. Many consider the carcass a blight, the graveyard a waste of valuable land. Today, the Silverdome acts of a reminder of a dream long dead. But on that cold day in 1982, it’s where a football dynasty was born.

* * *

C. Don Davidson spent nearly a decade doing all he could to make the Silverdome a reality. A Pontiac native, Davidson’s obsession fully took hold in 1965 when he tasked his urban planning class at the University of Detroit with devising a plan—complete with a state-of-the-art stadium—to revitalize the city. “We’d go to my grandmother’s house every Sunday, and I’d watch my uncle Don draw stadiums on napkins at the dining room table,” says McVety.

In his quest to make the Pontiac Plan a reality, Davidson even started his own newspaper, The Pontiac Times, in 1972 as a way to push the agenda. As a member of the Metropolitan Stadium committee, he finally helped lure a facility to the city in 1973. “No one can say that Don Davidson didn’t try to make Pontiac a better place,” former Downtown Development Authority member Jack Kent said in Davidson’s Oakland Pressobituary after his death in 1987. “By god, he tried.”

Ten days after the Lions finished their inaugural season in Pontiac, Elvis was on stage in the Silverdome, ringing in the New Year. In 1984, Michael Jackson brought his Victory Tour through town. Twanisha Potter, who grew up in Pontiac, was 11 years old when she passed the dome on that night in August. “We were literally crying because we couldn’t go,” she says. The only man who could upstage both the King and the King of Pop—the Pope—welcomed more than 93,000 of his closest friends for a mass in 1987.

As big as Michael Jackson was at his post-Thrillerpeak, there still weren’t 68 million people watching him moonwalk live. Even now, the Silverdome concourse has signage boasting about its role as the home of Super Bowl XVI. In September 1981, when the San Francisco 49ers opened their season against the Lions, a banner commemorating the coming game hung near the field. During a Saturday practice on-site, left tackle Dan Audick told guard John Ayers the offensive line should take a group photo in front of it, just as a memento. “He said something to the effect of, ‘We’ll get that one later,’ as though he had a sense of how good a team we were,” Audick says. That weekend, as the Niners lost to Detroit 24-17, Audick wasn’t so sure.

* * *

It was just after 6 p.m. on Aug. 17, 1981, when Chargers coach Don Coryell found Dan Audick and tapped him on the shoulder. The fourth-year tackle had been traded to San Francisco. And they wanted him there the next day. “I asked him, “Could you tell them to give me one day to make the transition?’” Audick says. He got his day, and when Audick got to San Francisco on Aug. 19, he found a team that was far removed from where the Chargers were in 1980. Joe Montana was opening his first season as a starting quarterback. Dissatisfaction with the secondary had led the Niners to draft defensive backs in the first three rounds. All three were slated to start. And Audick would later learn that after going a combined 8-24 in his first two seasons, head coach Bill Walsh had contemplated resigning. The previous year, Audick was standing in a huddle with Dan Fouts, Charlie Joiner and Kellen Winslow in a narrow AFC Championship Game loss to the Raiders. Now he was the starting left tackle for a team that went 6-10 and hadn’t sent a single player to the Pro Bowl a season earlier.

Carmen Policy wasn’t yet working for the 49ers in any official capacity, but the future vice president of the franchise was already doing business for his friend and team owner Eddie DeBartolo. That included his involvement with bringing in Walsh. When DeBartolo told his father that Walsh was his top choice to replace Joe Thomas before the 1979 season, members of the NFL establishment, including Paul Brown and Joe Robbie, lampooned the idea. Walsh was a bit too Stanford, “maybe a little too professorial,” Policy says. “The basic tenet of their argument was that he didn’t have the emotional toughness to deal with being a head coach in the NFL year after year after year.”

• ROAD TO SUPER BOWL 50: Jenny Vrentas on Vince Lombardi’s lasting legacy, and final resting place

By the end of Walsh’s second year, it seemed as though they might be right. But in the lead-up to the 1981 season, Policy felt a shift. “You could sense a difference in Bill,” Policy says. “His eyes were sparkly. You could sense that things were coming together.” Sending quarterback Steve DeBerg to the Broncos had solidified Montana’s ownership of the offense, and it was starting to show. The injection of youth gave the back end of the San Francisco defense a speed and ferocity it had lacked, and the sole veteran of the group was able to provide a calming force the rest desperately needed. “Dwight Hicks had a certain smooth, refined value—patina, if you will—that he was able to administer to the secondary,” Policy says. “That unit, combined with some of the elements that Bill added to the rest of the defense, everything just mixed well.”

The final piece, the one that finally brought it all together, arrived five weeks into the season. Pass-rushing star Fred Dean was feuding with Chargers ownership about a new contract, and eventually, the spat with Eugene Klein ended with San Diego sending Dean to the 3-2 49ers. After the deal was done, assistant defensive backs coach Ray Rhodes approached Audick, Dean’s former Chargers teammate, and asked if he thought Dean would actually make an impact. “My words were simple,” Audick says. “’He’s legit.’” That Sunday against Dallas, Dean terrorized Danny White for four quarters, collecting four sacks (not yet an official stat) and a handful more hits. “What I used to say about Fred Dean is that he’s not a normal human being,” Audick says. “He’s made out of titanium. And when he could hit you, he could break you.”

San Francisco won its next two games, including a 20-17 nail-biter against the Rams before arriving in Pittsburgh to play a Steelers team that still featured nearly all the Hall of Fame talent from its Super Bowl heyday. “That particular year was a voyage,” wide receiver Mike Wilson says. “We didn’t know where we were going, but once we beat Pittsburgh in Pittsburgh, I really think that was the turning point for us to start believing.”

“All of a sudden,” Policy says, “it was a moment of awakening where we started looking at ourselves and saying, ‘Holy mackerel, we might just be pretty good. That took us from the level of, ‘This is going to be a much better season than we’ve had in a long time’ to the idea that ‘We can compete in this league.’”

The 49ers lost just one more game for the rest of the season. Their defense allowed more than 17 points only once after Dean’s arrival and finished second in points allowed, up from 26th the previous year. They had gone from a team with no Pro Bowlers to 13-3 and the NFC Championship Game, and somehow Audick was in the same position he’d seen in San Diego. “I wouldn’t have said, ‘Hey, we’re going to the Super Bowl on that [first] weekend,’” he says. “There was a lot of apprehension about how good we could be. But I didn’t know who Joe Montana was. I didn’t know who Dwight Clark was.”

Policy was sitting in the press box for The Catch. At first he thought Montana was trying to throw the ball out of bounds. Then Clark snatched it from the air. Nearby, a woman who worked the 49ers’ charter flights and helped at the stadium on game day popped a bottle of champagne. Problem was, there was still almost a minute left in the game. “I told her, ‘Try to put the cork back in!’ ” Policy says. “Get the bottle out of here! This game isn’t over until there’s zero, zero, zero on the clock.” When Dallas started marching down the field, she burst into tears. “I was telling her, ‘Take it easy!” Policy says. “’Don’t worry about it! Popping the bottle of champagne doesn’t control what happens on the field.’” After a game-saving tackle by Eric Wright and a game-sealing fumble recovery from Jim Stuckey, the tears stopped.

“We weren’t even aware of how impactful that moment was,” Wilson says. “We knew of Super Bowls, but we didn’t realize Dwight Clark’s catch was going to change our whole destiny.”

* * *

One thought hit Audick as he stepped off the plane in Detroit the week of Super Bowl XVI: “This ain’t New Orleans.” The previous season, reports surfaced about the loose leash Tom Flores had on his party-loving Raiders in the Crescent City. Bill Walsh would run into no such trouble in frigid Michigan. “It was our first Super Bowl,” Wilson says. “It could have been in Anchorage, Alaska. It could have been anywhere. We wouldn’t have cared.”

Walsh’s team spent most of its time bundled at the hotel. One centrally located room was outfitted with an Atari and two Pac-Man machines. Another housed a ping-pong and pool table. “I didn’t care about getting out,” Wilson says. “Families were there, and they went to do different tours. But honestly, I think we were focused on trying to win that championship.”

On game day, snow hit Detroit, and to make matters worse, vice president George Bush was attending the game. His motorcade savaged traffic patterns on the way to Pontiac. Policy had left earlier than usual because DeBartolo had television obligations before kickoff. The pair shared a car to the stadium with O.J. Simpson, but even in the early afternoon, the roads were slammed. DeBartolo asked to be dropped off near a parking lot a few hundred yards from the stadium, so there they were—DeBartolo, Policy and O.J. Simpson, jogging through the lot as fans yelled to Simpson that this wasn’t a Hertz commercial.

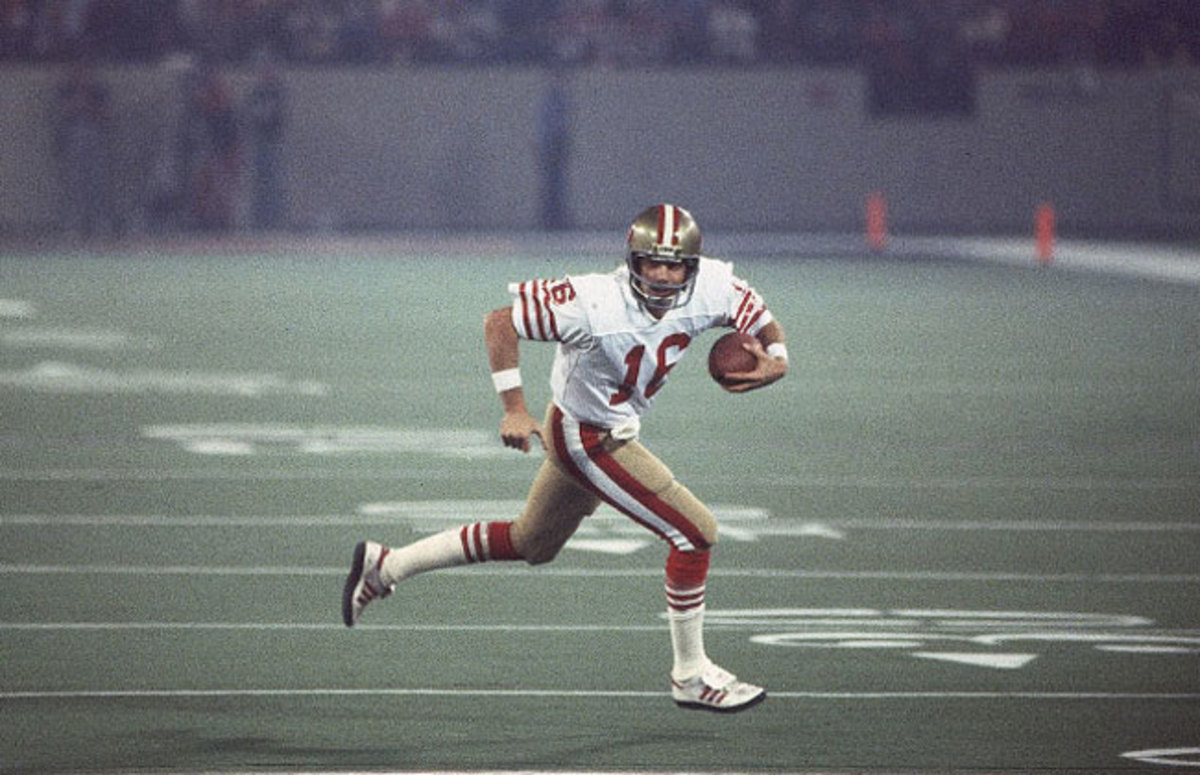

When it finally came time for the 49ers bus to pull into the Silverdome lot, traffic had come to a standstill. Half the team sat there on the highway, the dome frustratingly in view. For some of the more superstitious and ritualistic Niners, getting thrown from their pregame routine was torture. “Hacksaw [Reynolds], during that time, he’d be dressed for the game during breakfast at the hotel,” Eric Wright says. “That’s how edgy he was.” In an effort to defuse the tension, Walsh got on the bus PA. There was good news and bad news, he said. The bad news is that the game had started without them. The good news is that equipment manager Chico Norton was playing quarterback and had just throw a touchdown to fellow staffer George Cosmo, so the 49ers had a 7-0 lead. “I think it really worked,” Wilson says. “It kept the team loose and free. In hindsight, a lot of the guys felt like we didn’t have time to sit there and think about how big the Super Bowl is. We were more consumed with being behind schedule.”

Walsh’s antics had dominated the week. When the team plane hit the tarmac in Detroit, it arrived to an overeager porter who did all he could to pry Joe Montana’s bag from his hand and a tip from his pocket. The porter was Bill Walsh in disguise. “They say he gave the bellman $20 [for his uniform],” Policy says of Walsh.“Let me say this—if that bellman got $20, it didn’t come from Bill’s pocket, because he never carried cash.” In the locker room before kickoff, one 49er with a boom box was blasting the recently released “Physical” by Olivia Newton-John. Rather than stare into the big-game void, Walsh bounded about the locker room, dancing and shadowboxing in the faces of his players.

Walsh had been a boxer at San Jose State, and fight analogies permeated his pregame speeches, but in this instance it was more about a coach with a firm feel for the pulse of his team. “Outside his game-planning and the Xs and Os, he was a motivator,” Wilson says. “He made guys play way beyond even what they believed they could do. The proof was us winning in 1981. To every man, we loved him to death.”

Just before kickoff, Policy sat in a suite with DeBartolo and ESPN’s Paul Maguire. When the waitress asked if any of them wanted a drink, Maguire ordered a Bloody Mary, and as much as DeBartolo wanted to take the edge off, he and Policy conceded that it was a long day. They should probably stay sharp until the end. “Then Famous Amos Lawrence fumbles the kickoff,” Policy says. “Eddie looked at the bartender and said, ‘I think I’ll have that drink now.’”

• ROAD TO SUPER BOWL 50: A Superfan who’s been to all 49 gears up for SB 50

* * *

Cincinnati took over at the 49ers’ 26-yard line, but disaster was averted when Dwight Hicks intercepted Ken Anderson in the end zone just a few plays later.

San Francisco jumped out to a 20-0 halftime lead, and despite the Bengals eventually cutting the game to five in the fourth quarter, Montana and his team kept control throughout. A team with no established stars when the season began had just won a Super Bowl. The way Policy remembers it, that relative anonymity the 49ers enjoyed coming into 1981 was actually whythe ride was even possible. “They all kind of saw each other as equals trying to accomplish something really special,” he says. “It was a perfect environment for Joe Montana to work his magic. He just has this thing about him that attracts people to who he is and what he does and how he does it.”

By the time the 49ers left the Silverdome that day, a dynasty had begun, but it was birthed with a cast of players no one could have expected. “Walt Easley. Ricky Patton. Johnny Davis. Earl Cooper,” Audick says. “In NFL lore, these are not household names. But we had a lot of players on that particular team that were not Pro Bowl-caliber but played on Sunday, individually at a level where they contributed in a synergistic way.”

When Policy thinks about it now, his mind goes to the perfect dinner. “It was as though you went shopping, and you bought quality ingredients, but nothing was the highest price,” he says. “But when it was all put together, cooked in exactly the right way, and mixed with the proper sauces, the end result was beyond gourmet perfection.”

INSIDE THE SILVERDOME Photos by Carlos Osorio/AP

Inside the Silverdome

Your table is ready.

Plants grow through the turf.

Electronic gear still sits in the booth.

Even the roof, seen here in 2014, is gone now.

The tattered remains of a suburban stadium dream.

Wilson would go on to win three more Super Bowls in San Francisco, but he maintains that the first was the most special. He admits that it’s strange to know that in a few short months, the place where he had his first great memory as a 49er will be gone. But the Silverdome’s demolition is just the latest bit of proof that time marches on. Last season San Francisco said goodbye to Candlestick Park. “You go drive down the 101, and it’s gone,” Wilson says. “That’s the thing about the game.”

It won’t be long until a wrecking ball smashes through the Silverdome in the way Montana and his team tore through the NFL, but until then it’s left for the wind to tear at its bones, for the concrete to crack, for the metal to rust. Soon, all that will remain are the legends it helped create.

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.