A Man, the Arena, and His First KISS of Fate

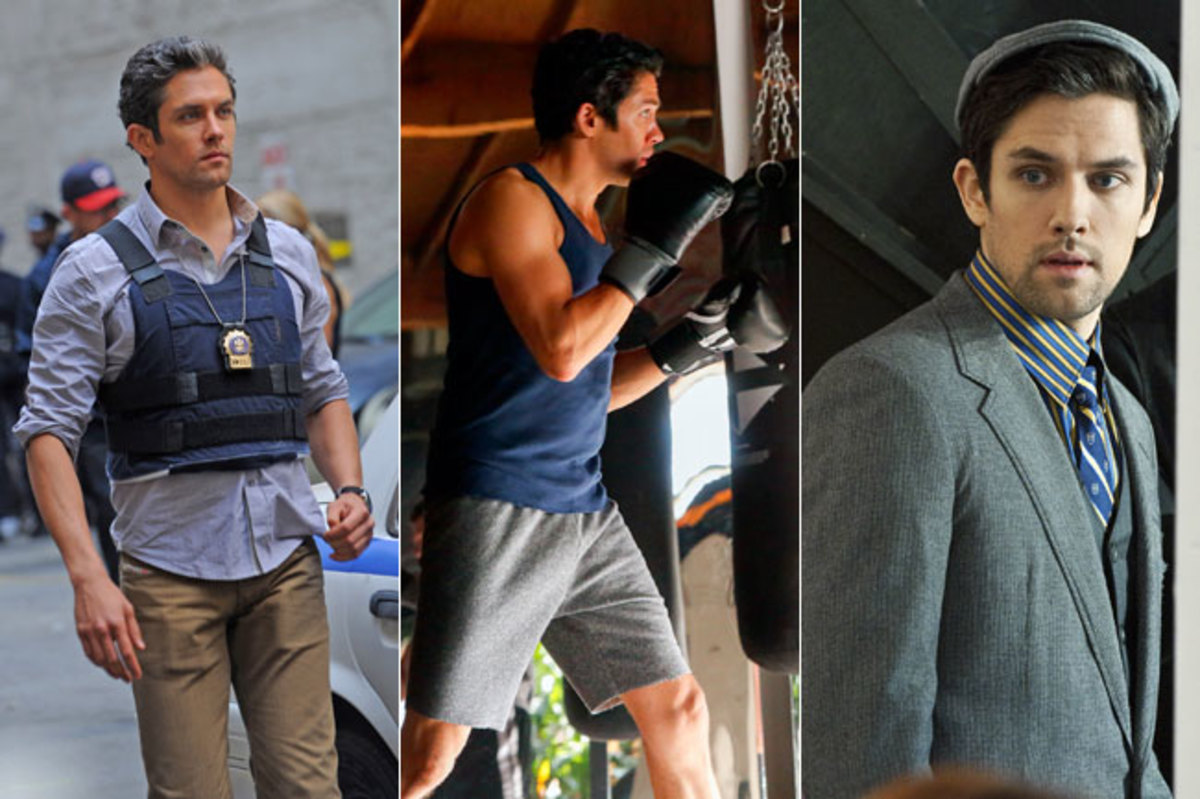

Editor’s note: You may recognize Neal Bledsoe for his roles on The Mysteries of Laura or The Man in the High Castle, or for his stint as an Old Spice Man. Beyond acting, he’s been a contributor to The MMQB since writing an essay about his beloved Seahawks before Super Bowl XLVIII. In the months to come, he’ll chronicle life in the Arena Football League and his quest to make the roster of the LA KISS. There’s no other way to say it—break a leg, man.

The Eyeball Test

Santa Ana College

December 5, 2015

SANTA ANA, CALIFORNIA — That first tryout I was only there to observe. I had to remind myself that the hits would be real very soon, but on that day all I was there to do was watch. Still, the actor in me wanted to be authentic, so I carried myself with what I perceived to be an authoritative air: a veteran who’d seen this all before, maybe even a little bored by it all. But under a composed mask my mind raced and my guts churned with fear and excitement. I had barely settled on what position I’d hoped to play: receiver. It was from that spot I felt I could get the best sense of this mercurial cousin of the NFL.

When I told people I would be trying out for what at the time was Los Angeles’ only pro football team, the LA KISS, they thought I was out of my mind. They’d cock their heads to one side, consider my mental stability and ask, “You mean as the kicker?”

I’d shake my head and tell them what I wanted to play.

“You’ll be killed,” they’d say. “You can’t play receiver. Those men will mash you. You’ll be broken. And what about your face? You’re an actor after all.”

“That’s what face masks are for,” I’d tell them.

I saw a Plimptonian opportunity. But my aim was to answer a slightly different question: What is the true difference between the professional and the amateur when the world considers the pros themselves to be amateurs?

I knew I didn’t want to be the kicker. There wasn’t enough action to be had there, chipping shots through the uprights at the end of the drive like some ceremonial ribbon cutter. Receiver is where the game is truly played. Those are the men who catch passes and end up, ass-over-tea-kettle, in some lucky fan’s nachos in the front row. I knew my agents, my mother and my editor would be more comfortable with me playing anything but receiver. However, I sensed within me a deep reserve of untapped potential. I was determined to prove that, at 34, I could still do anything.

This is the Arena League. It lives for the NFL like a cruel reminder of its humbler origins—like a drunken cousin Eddie who asks you for money after you’ve moved to the big city and made good. It is a Norma Jean to a Marilyn Monroe or an Archie Leech to a Cary Grant—a ghost from the NFL’s past. The Arena League is what football was before the NFL made it a kaleidoscope of dancing robots, Cialis, Draft Kings, light beer and pickup trucks. To borrow from my favorite 1980s PSA, “This is your game. This is your game without funds. Any questions?”

More specifically, I wanted to spend time with the LA KISS, the only pro football team in L.A. before the Rams were given permission, in January, to make the move from St. Louis. Before then, the KISS, whose owners include Paul Stanley and Gene Simmons of the band KISS, existed in the vacuum between the “semi-pro” teams at UCLA and USC and the great freeway expanses north and south, where the NFL still lived in the Bay Area and San Diego. The average Angeleno was oblivious to the fact that we even had a pro team. So on the eve of their last season alone in L.A., I saw a Plimptonian opportunity.

More than 50 years ago, Sports Illustrated’s George Plimpton explored the true difference between the professional and the amateur in Paper Lion. But my aim was to answer a slightly different question: What is the true difference between the professional and the amateur when the world considers the professionals themselves to be amateurs?

I arranged to report the series for The MMQB in New York and then had a meeting with the LA KISS to pitch the idea. They liked it, but there were obvious questions about how I’d hold up. When I made my intentions known to the KISS’s CEO, Joe Windham, he invited me to watch their first open tryout. He thought it would be wise to get an idea of what I was in for.

“We have two tryouts. One in December and one right before the season in February. It might be a good idea to see what you’re up against,” he said. “But just so you know, we’ll pull the plug if it looks like you’re gonna get hurt or if you’re gonna hurt someone else.”

One of these things, I thought, was far likelier than the other.

When the morning of the first tryout came, I drove the 32-mile expanse between Downtown Los Angeles and Santa Ana College. A December chill had plunged the overnight temperatures all over Orange County into the 40s and a layer of dew clung to everything: cars parked overnight in the lot; signs that read “REGISTRATION, WAIVER, NUMBERED TAGS AND T-SHIRTS”; the black iron fence and the aluminum benches; even the green plastic turf of the field itself; everything was heavy with the damp of a winter’s morning in the desert.

But the chill failed to dampen the hopes of the men who’d come to make the team. By 7:30 more than a hundred were lined up. They filed through, one by one, to pay their registration fees: $100, or $80 if they had signed up early. They signed waivers, which released the team from any legal responsibility for their safety. Finally, they pinned their numbers to “free” T-shirts that read, “LA KISS Open Tryout” and walked through the gate and onto the field.

I thought of all the tomorrows I tell myself I still have, and wondered how true that really was anymore. God knows I’d shanked a few chances in my life as well.

They all looked like football players. There was a confidence to their bodies that only their sport can mold. It’s that unmistakable mixture of strength and grace, groomed by years of positive reinforcement. Most were in their early 20s, a couple were in their 30s, and one gray wolf looked to be knocking on the door of 40. They wore layers of sweats, hoodies and warmups. A quarterback, his legs thin enough to make his tights look baggy, practiced throwing 30-yard bullets over and over to a phantom wideout running routes between a Prius and a pickup truck, while he waited for the line to move. His T-shirt advertised himself as an in-home personal trainer. It read, “We come to you.” A few had adopted the Nylon Ninja look peddled by Under Armor and Nike. Some bore the stamp of their four-year colleges, while others proudly wore the faded emblems of other Arena teams, but their message was clear, “Trust me, I’m almost professional.”

A few wives, girlfriends, moms and dads had come, too, acting as personal coaches for their players. They rubbed backs, threw footballs and directed their guys through warmups.

One mother asked her son if he had filled out his paperwork correctly.

“Yes, mom,” he said quietly, as he passed his paperwork to the new director of personnel, Dan Frazer.

She reached to take his number from his hand, to pin it to his shirt, like a tux flower before the prom.

“I got it, mom,” he said, his voice low but chin held high. He put down his bag and pinned the number himself, then gazed upon the grounds. It was here, he must’ve thought, where he would begin to prove himself as his own man.

He wasn’t the only one swarmed by a mother’s defensive instincts. One beanpole of a kid, who couldn’t have been older than 21, was flanked by two older women. I reckoned one of them had to be his actual mother, but the other woman perplexed me. She looked almost identical to mom. Was it possible that he had brought his mom and his aunt? They passed by me like two Praetorians in front of a Roman Emperor and guided their rickets-thin Augustus to the bleachers, where they watched him tie his shoes.

The players carried a colorful galaxy of tools to prepare for the grueling day in the desert sun: heavy jugs of water, foam rollers, massive headphones—some almost as big as the cleats that dangled from their necks—balls, and Spider-Man gloves. I got the sense that even if this was their first pro tryout, these guys all knew the drill. Warm up. Get loose. Bring your lucky gear. Then be ready to play.

I asked one player why he was here. “Just got too painful to keep watching the game on TV,” he said. Shit, I thought, that’s why I don’t watch the Oscars.

The serious ones were easy to spot. They had a focus and desire that everyone else lacked. While some of the hopefuls began to think this was a terrible idea right then and there, others exuded a hardness that refused to be broken.

One sleek defensive back had flown in from Wichita and put himself up in L.A. As he told me his story, I did the math in my head. He forked over a hundred bucks to try out, three hundred for his flight and another couple hundred to house and feed himself while here. Then, if he made it through this round, he’d simply have to repeat all of this for the next round. At the end of the day he’d have to pay more than a thousand dollars just to try out. Then, if every break went his way, all he stood to make was $820 a game. I asked him why he was here. He responded, “Just got too painful to keep watching the game on TV.”

Shit, I thought, that’s the same reason I don’t watch the Oscars.

Just inside the gate, head coach Omarr Smith paced back and forth on the pitch. He shook hands with the other coaches while chewing sunflower seeds and spitting the shells into a plastic bottle. He greeted the players with a nod as they sauntered in to get loose. Coach Smith had just been hired from San Jose when the team parted ways with its first coach. After two seasons as the league’s resident cellar dweller, the KISS wanted someone to help them win. Omarr was a seven-time Arena Bowl champion—four as a player, three as a coach. Everywhere he went, he won. It was felt that he was the right man for the job.

“Hey Coach,” I said, my hand extended to shake his.

“Morning,” he said as we shook.

The first time I met Coach Omarr, at team headquarters for my introductory meeting, I shook his hand as if I were trying to make the team right there next to the gold KISS record on the wall behind the receptionist’s desk. Some insecure voice deep within the recesses of my inadequacy told me to squeeze harder than he did. I did that, but in my temporary mania I also shook a beat too long. He looked at me sideways, but since it was the first time we’d met, he was polite and said nothing. With this second chance, despite my best efforts not to, I did the same thing. But like a chef desperate to fix bad fish as it leaves a kitchen, I peppered this shake with steady eye contact. I heard that voice again; it whispered, “This is how real men shake hands.” I could only hope that Omarr passed it all off as my being from a land of unusual handshakes. If he ever asks, I’ll blame it on my being born in Canada.

I asked him quickly what he wanted to find today.

“It’s a look, you know?” he said.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“You just know when someone’s a football player. When they walk on the field.”

“I see,” I said.

I didn’t see. But I looked around the field as if I did. Besides the extremely obvious cases, the ones who looked like liabilities in a pickup game in the park, they all still looked like football players to me. All I could offer him was a thoughtful, “Hmm.”

“It’s like you,” he said, seeing that I didn’t get it. “You walk into a room and people are like, ‘He’s a model.’ ”

I took a beat.

“I’m not a model.”

“Really?” he asked, surprised.

“I mean, I’ve modeled once, but I don’t…”

“Alright, then you’re a model.”

I felt like I had just lost something. Perhaps it was my manhood.

Just then, a player came up and introduced himself. He told Omarr that another coach somewhere in their mutual history insisted he say hello.

“Oh, OK,” Omarr said with a nod, before spitting another sunflower seed into the bottle.

The player smiled, then rattled off other names of other coaches whom Omarr had apparently never heard of. They talked about the game for a bit—where he played, what he played and how well he played. They shook hands, like normal people do, then the player smiled and walked away to get loose.

“See, that guy went to a four-year school, so you can tell that he can play a little bit. But these other guys, they’re weekend warriors.”

“What do you mean?” I asked. “Like someone who does CrossFit and thinks it’ll transfer to football?”

“Yeah, kinda,” he said. “It’s like this guy.” He pointed at a young guy with hunched shoulders, a bit of a potbelly and a skullcap that made him look like a demolitions expert from a cheap Italian remake of The Dirty Dozen. “This guy just doesn’t have the body. You know, maybe on a larger field, maybe… But this is the Arena League. You gotta be fast and explosive.” He spat another sunflower seed. “It’s an eyeball test.”

What do I know about eyeball tests? I’ve been subject to them all my life. We all have. But as an actor, I’d specifically been in these players’ shoes before. Omarr was right. I had modeled once. I’d also played an alcoholic model on TV, an Old Spice Man, a baby-stealing lawyer, a Nazi, a drug addict, a blue-collar food truck driver from Queens, solved crimes on every procedural in New York and committed crimes of the heart on every soap opera in the city as well. To get all of these jobs, to put food on my table and keep a roof over my head, I have had to submit myself to hundreds of eyeball tests. So here, I just reversed the process. The eyeball test is more often than not an experience without humanity—especially in the parallel abysses in which actors and these players found themselves.

At open call auditions in New York and L.A., actors queue up like lambs to the slaughter. It was the same with the guys on the field. A hundred hopeful people, with no one believing in them but themselves. All nerves, with so much desperate hope crippling what little shot they had. All I could think then and every other time was, “You’re doomed.” But then, quickly on its heels, another thought. “There, but for the grace of God, go I.”

I walked around and tried to conduct my own eyeball test. Were these not football players? I guess some were too small. Others might have been too big. Some were way too big, bordering on obese. That young guy with his mom and aunt looked more like a baby giraffe than a football player. There were a few of those in fact, with legs like young foals and wide scared eyes. A few had no business being here, I thought. The CrossFit warriors looked jacked, the kind of guys you see at the gym and think, Wow, you must spend a lot of time here, but they just looked like they were in good shape, not football players. The more and more I looked, the less and less professional these guys appeared. Still, one or two had some promise, I thought. Just maybe.

“Hey Nate,” I heard from behind me. I ignored it, because my name isn’t Nate. Still, the voice persisted. “Nate, it’s me!”

I turned to see a grandfather staring at me.

“I’m not Nate,” I said.

“Oh, sorry, I thought you were Nate.”

“No. Who’s Nate?”

“Nate Stanley,” he said.

A blank look settled on my face.

“The new quarterback,” he said, “from San Jose.”

“Oh yeah,” I said, remembering the quarterback the KISS had just signed a month ago. Everyone was very high on him. “Yeah, no, I’m not him.”

“Well, you look just like him.”

“I’m Neal,” I said, extending my hand.

“Obie Rambeau. I’m Daniel Frazer’s grandfather.”

We shook hands without incident, and immediately I was proud of myself. I had passed both his eyeball and his handshake test. I hadn’t even laced up my cleats yet. The sky was the limit for me.

“You see any players out there?” I asked him, excited to compare notes on criticism.

“A few,” he said.

“What do you think, like five percent?”

“Nah,” he said, like a prospector. “Maybe like, mmm… one percent.”

“How can you tell?” I asked.

“It’s a look. You can just tell. Like this guy, you see this guy?”

He pointed to a receiver who ran in an easy trot and caught everything thrown his way, even a few balls one-handed. He looked like he had complete control, as if everything was just pure play.

“I like him,” Obie said. “Some of these other guys look like they haven’t played in years. Or like they’ve not been training.”

“They’re not in shape?” I asked.

“Yeah, like they’re just waiting for the phone to ring before they start to work. The guys who make it are working their butts off, so when the phone rings they’re ready. Other guys just wait for someone to tell them where to be. And then they come here and they’re too jacked up.”

“Too nervous, too much adrenaline?”

“Yeah. Just out to prove something. And that’s when they get hurt. Someone always pulls a hamstring in the forty.”

They continued to warm up. A whistle was blown, and the coaches herded everyone toward midfield. Coach Omarr was waiting for them. They took a knee; the tryout had begun.

“This is a job interview,” Coach Omarr began in his low-key manner. “Treat it as such. Everything you do is evaluated. How you carry yourself. Body language. It’s not just about your scores and times. You know, if someone runs a 4.5, but is just dogging between, and another guy runs a 4.8 but has a great attitude, I’m gonna take the guy who runs a 4.8. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Coach,” they all agreed.

Then Omar wrapped up his speech and called them into a huddle.

“Time to go to work! LA KISS on three.”

“One. Two. Three. LA KISS,” said the men who’d come to make the team.

You Know the Drill

After warming up together, the players split off into five groups to be tested at different drills set up around the field. These tests were designed to measure the raw physical gifts that each possessed. Or, in some cases (such as mine), hoped to possess.

The first group headed for the bench. Here they had to bench press 225 pounds as many times as they could. I recoiled in fear that if I tried this exercise I’d be pinned beneath the bar like a bug beneath a staple. Then the men began to try their strength like it was a carnival game.

“Bounce it off your chest. Keep your back against the bench!” barked the coach who ran the drill.

One barrel-chested lineman pumped out reps like he was a diesel-fired piston. Ten went by in a flash. Then 20. A chitter of encouragement rose from the other men as they watched him go. He started to struggle around 25. “There you go, big man, there you go!” someone yelled. Another big guy hollered, “Gotta eat! Gotta eat!” over and over again, as if speaking to everyone and no one all at once. With one final thunder the lineman shoved the bar back from his chest and cradled the iron. He was done. Next man up.

The best score was 30 reps. Several guys made it into the mid-20s, some could only pop out a handful, while some struggled and strained under the bar like I imagined I would. A few guys refused to do it altogether. A small mouse of a man just shook his head at the iron rig, as if he were morally opposed to the exercise. A quarterback, who looked like the new boyfriend of every ex-girlfriend I’ve ever had, refused as well. However, the gunslinger’s reasons were different: The mouse couldn’t do it, but all the QB had to do was throw. No reason to mess that up trying to impress with a barbell.

The second group headed for the broad jump. The players had to jump as far as they could from a dead stop and stick the landing. This one should have gone fairly well for everyone. I mean, who can’t jump? The answer was a lot of people. Each man got two tries. Some fell, some stumbled, and by result, some scores were pitifully low. The best men here, the human frogs among the group, jumped 10 feet.

“Hey, where did you get that hat?” I heard a voice ask me.

I turned to see a spindly tower of skin and bones staring at my Lucha Va Voom hat, a local favorite in Downtown L.A., which advertised “Sexo y Violencia!”

“What’s that say?” he asked.

“Lucha Va Voom,” I said.

“Lucha Ba Boom?”

“Lu-Cha-Va-Voom,” I said slowly. “Lucha Va Voom.”

“What is that?”

“Mexican wrestling and burlesque.”

“Cool,” he said. “That’s pretty cool. Burlesque, is that like strippers?”

“Sure, and wrestling. Mexican wrestling.”

I went back and watched the men jump for a moment. Then I heard him again.

“But, like, it’s girls right?” he asked, concerned. “No men?”

“The men wrestle,” I told him. “The girls do burlesque.”

“Cool,” he said.

He stood well behind the jumpers. I gathered he was not here to try out. He was just a friend of someone who looked like a CrossFit instructor. Wives, girlfriends, moms, dads and now beer buddies. Support came in all shapes and sizes.

“Hey,” the lanky friend called out to the CrossFit instructor. “Look at this hat. I think that would be a good Wolfpack night.”

“What’s the hat say?” the CrossFit guy asked.

“Lucha Libre. It’s strippers. And wrestling,” said the friend.

“Where is it?” he asked.

The CrossFit instructor attempted to circle behind me, to get a look at the hat himself. I turned it around for him.

“Downtown,” I said.

He read the hat like it was a scared text.

“Wouldn’t that be a good Wolfpack night?” the friend asked. “For the boys?”

They agreed it would be.

“So are you like a coach?” the friend asked.

“No man,” I told them, “I’m a high-priced free agent. They brought me in to finally put them over the top.”

“Cool,” said the CrossFit instructor. “Has anyone ever told you that you got the whole Josh Duhamel thing going on?”

“No, that’s a first today,” I said.

Quietly, I was delighted he thought so. Another quarterback! At least people were starting to think I look like actors who’ve been football players. (Duhamel played QB at Minot in North Dakota.) If I get Dean Cain, I might have to try out for the NFL. (Superman was a safety at Princeton.) I asked the CrossFit instructor what position he wanted to play.

“Anywhere they think I’d fit,” he said. “How many you play? Ten? Eleven?”

“We play eight,” I told him.

He furrowed his brow and looked out on the field. My answer had troubled him. Even the color of grass was different for him now.

“Have you played before?” I asked him.

“Yeah, I mean, a little,” the CrossFit instructor said. “I just found out about this two days ago.”

I was surprised. I assumed this must have been a long-held dream for everyone here. Why else would you play such a brutal version of such a brutal game? His approach was almost like he had found a group fitness class he wanted to take. Maybe he just thought it sounded like fun.

“And, you came down to make the team?”

He nodded.

“You should play receiver, bro,” his friend told him.

“You think?” he asked.

“Yeah, bro. Definitely receiver,” said the friend.

I began to walk away when the friend called to me.

“We definitely have to check that place out. Strippers and wrestling. Cool.”

I could see guys begin to give up on themselves. A few crumpled like empty soda cans under the pressure.

The third and fourth groups headed for the agility drills—the three-cone and the short shuttle.

In the three-cone drill, three cones are spaced five yards apart in an L shape. The player had to launch himself from the first to the second cone, stop on a dime, touch the ground, race back to the first cone, stop on another dime, touch the earth again, run back to the second cone, make a sharp right turn, run a figure eight around the third cone, then make another sharp turn at the second and sprint back past the first cone.

If those directions confused you, you would have fit in quite nicely. Half the guys were lost like student drivers without GPS. I could see guys begin to give up on themselves, and in a few cases the easy camaraderie of the day gave way to a dog-eat-dog hierarchy. Those who had some chance were given attention and encouraging yips by fellow players as well coaches. Those who obviously wouldn’t make the team were left to run drills of silent mediocrity. They were fighting not just the odds but indifference.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/JoP2XqSv9WE&w=650&h=433]

At the short shuttle, cones were placed in a horizontal line five yards apart. A player started at the middle cone with one hand on the ground. Then he had to push off and burst five yards to his right, touch the ground and pivot back the other way, burst 10 yards to the far cone, touch the ground again and pivot back to burst the final five yard back past where they started. As much as these drills were supposed to measure change of direction, they seemed more to challenge each player’s ability to take directions. Guys turned the wrong way, or couldn’t move laterally, or put the wrong hand down, or turned the wrong shoulder. Coach Omarr ran this drill, and you could see that everyone felt that this was their big chance. Almost like me and handshakes. While some did well, quite a few crumpled like empty soda cans under the pressure.

The last group headed for the 40-yard dash. This was all about pure burner speed. Starting from a three-point stance, the player’s arms cocked like the hammer of a pistol, they exploded off the line, their knees driving as high as they could go and their legs kicking violently into the turf. Some runners clearly had been track stars, but others stumbled awkwardly through the dual stopwatches of the two coaches at the finish line. The coaches encouraged the big men most of all. They seemed more excited about the prospect of a fast lineman than wideouts or defensive backs.

“C’mon, Big Man,” they’d shout. “Push, push, push, push.”

Contrary to what Obie predicted, no one pulled a hamstring in the 40. For those that had it, their speed was blinding. Certain guys had so much grace when they ran that it hardly looked like effort at all. They almost slowed time down for themselves and merely strode through it like it was the most natural thing in the world. I imagined myself running the 40. A herky-jerky spasm of knees and elbows flailing in six directions at once, crossing the finish line somewhere around the minute mark.

As the players were put through the paces I saw team CEO Joe Windham taking it all in, calmly evaluating these men who hoped to make his team.

Joe came from the Arizona Rattlers, as a replacement for the first-year regime of Brett Bouchy and Schuyler Hoversten. When Joe got here the KISS were one year removed from trying to take the league by a storm of pyrotechnics and laser shows. Jumbotrons displayed demonic armies marching to victory, while the players clad in the fire, black and silver of the home uniforms pounded the guitar pick emblem at midfield. Pregame spectacles were often so elaborate they delayed kickoffs, once by 45 minutes. Stripper poles were hung on platforms at the four corners of the Honda Center, and “cheerleaders” gyrated cheerlessly through two halves of indoor football, win or lose—and it was mostly lose that season. Now that I think about it, it sounds a lot like Lucha Va Voom.

Arena Football has traditionally been a family affair, but the LA KISS tried to make it more like a KISS concert. That first season the fans ate it up, and the team’s attendance was second in the league. By the end of last season, however, the novelty was gone, and attendance (7,913 per game) fell to third worst in the league amidst a dismal 4-14 campaign. Only the New Orleans Voodoo and the Las Vegas Outlaws drew smaller crowds, and both folded at the end of last year. Clearly, changes had to be made.

I greeted Joe, and he asked me what I saw.

“Lotta hope. Lotta desperation,” I said. “Some guys look good.”

“Yeah,” he said, “it’s like that movie Major League. You remember the Cuban guy, played the president on 24?”

“Ceranno! Of course.” I said.

“Remember how he could just tee off on fastballs, but when they’d throw the curve?” he asked, before he paused for effect. “Lotta guys here can’t hit the curve.”

I wondered how trouble with the curve translated to football. But I got his point; even if some of these guys could do one thing well, they could only do that one thing. They might be fast but weak, or perhaps they were strong but too slow. I wondered if any of them had thought to elicit the help of Jobu and a fifth of rum, the same way Ceranno had. But then I was reminded of a different baseball movie, Bull Durham. Crash Davis asks what’s in it for him after his AAA contract is bought out so he can babysit Nuke Laloosh, and the answer the skipper gives him has always chilled me to the bone. He tells him, “You get to keep coming to the ballpark and keep getting paid to do it.” This was that kind of opportunity.

For those coming down from the NFL, this is their last stop in pro football.

“You see Donavan Morgan and Terrance Smith over there?” He pointed out two large men watching the drills. “We’re trying to build a culture here. Part of that is bringing guys like that back. Donavan was here when we didn’t take care of players, and I had to tell him things would be different.”

“Was it that bad?” I asked.

Apparently it was. There was no trust. With all the investment in spectacle, the players were just an afterthought. They had trouble signing free agents.

“We’re L.A.’s team, and people didn’t want to sign with us. We were like, Why? What’s up? So I’ve been trying to change that. By doing the little things. Taking care of guys. It goes a long way. Terrance was working as a foreman on a construction site in North Carolina, and it was thought that he would never come back. So when he signed with us, people thought we must be paying him under the table.”

Because all player salaries have to remain the same, each team has to find other ways to lure the players they want. Some teams will pay their stars a little something extra, or hook them up with a no-show job somewhere in the community. Sometimes teams are caught and given stiff fines for doing this. Other teams simply find guys good (and legit) part-time jobs with which they can augment their meager AFL salaries, in order to get the players they want.

As Joe sees it, the AFL serves as a sort of transition league. It’s there for the guys who need a break. Maybe they didn’t go to the right school, or have the right agent, or maybe they needed more time to develop. If a player catches the eye of the NFL, the league will support him and give him every opportunity to pursue that dream. But for those going the other direction, coming back from the NFL on down, this is their last stop in pro football. Joe doesn’t see his job like a traditional team CEO. Instead, he styles himself to be a life liaison, helping these guys develop skill sets for when the game is over. In the NFL the post-career hope might be something like owning a car dealership; post-AFL it might be something more like a job at a car dealership. Here, the hero’s return to mortality happens very fast.

“You’ve gotta have a plan B,” he told me. “Some guys might want to head to the front office or coach.”

“Do guys here do that?” I asked. “Do they split their time like that?”

“No,” he said, “They’ve gotta stay focused. If you have a plan B it takes too much away from plan A.”

Then Joe pointed across the field.

“You should talk to Kenny,” he said. “He just had a great minicamp with the Lions.”

I made my way over to where Donovan, Terrance, Kenny and a few of the other KISS players watched the tryout. The first thing I noticed was their size. At 6-3 and 190 pounds, I’m not a small man. These guys were roughly the same height and weight, but as I looked at them it was hard not to feel like they were genetically different, as if football had hardened their DNA. There was a gap between us that no amount of hours in the gym or plays on the field could bridge. Even the kicker looked superhuman. All of a sudden Coach Omarr’s talk about body types made perfect sense. These guys were football players. Face to face, you could just tell.

I arrived on the tail end of them teasing Kenny about having a boyfriend. Kenny doesn’t have a boyfriend. To hear the AMC documentary 4th and Loud tell it, he’s supposed to be quite the ladies man. Instantly I adopted a prison mentality and piled in on Kenny.

“Yeah, Kenny,” I said, moments after meeting him for the first time, “you should really be nicer to your boyfriend. He called me and he was really upset. Well, it’s not that he’s upset, he’s just disappointed.”

Terrance and Donovan laughed, and suddenly I felt like I was back in high school. Then Kenny laughed, too. I didn’t feel as awful after that.

“I heard you got pretty far with the Lions this year at their minicamp,” I said.

“Yeah, but I can’t miss anymore.”

“Meaning what?”

“I’m 29. I’ve gotta make them all. I could miss just as many field goals as a 22-year-old, but I have to be polished. He’s the 22-year-old with upside.”

Kenny Spencer was only 29, so young, but already he talked as if he had missed his shot. I began to speculate on all the tomorrows that he once told himself he’d have. Maybe at 22 he shanked a few at his first tryout and told himself he’d be back next year. Maybe he needed a few years to work out the yips. Maybe he pulled a hamstring at 25 and worked himself back over the next few years. Maybe this was how he found himself, at 29, losing out to a 22-year-old with “upside.” I thought of all the tomorrows I tell myself I still have, and wondered how true that really was anymore. God knows I’d shanked a few chances in my life as well.

Keep It Simple Stupid

The piercing trill of a whistle was heard. The drills were over. The offensive and defensive linemen went off to battle one another at the far end of the field. The defensive backs worked fiendish footwork drills that required a torque of the hips as if their lower halves were made of rubber. Finally on another end of the field the receivers paired up with the quarterbacks to run routes. Three lines were set up, with each group of wideouts being given different routes to run. Hooks, hitches, posts, slants and curls. Seeing as this was my newly chosen profession, I stayed with them, hoping to learn a few tricks of their trade.

I sensed that this was where many of the receivers felt they would shine. The majority of the players who had come to try out were lined up here too. It was the simplest position in terms of what was asked. Sure, many of them felt they didn’t have the raw athleticism to jump nine feet, or run a 4.3 40, or fight in the trenches, or dance the backward ballet of the defensive backs, but every single one of them knew they could at least catch a football. They were all sure of that.

That was until the footballs actually started flying toward them. The quarterbacks, who themselves tried to impress the coaches with how hard they could throw, fired bullets that sailed through the hapless arms of the receivers. The quarterbacks would then kick the dirt, disgusted, the fault always with someone else. As the receivers realized how in-over-their-heads they were, some of them gave up. You could see it in the way they jogged back to the line. It wasn’t like, “Damn, I know how I fix it.” It was, “Damn, I’m done humiliating myself, and I’d like to go home now.” I identified with those men most of all, yet as I looked on I wanted them to keep at it. To try their damnedest. Their quit made me pity them and loathe them. It might have been the fear of the quit in me.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/1sTRbw-nbs8 &w=650&h=433]

A coach, who introduced himself only as Skinny, said he was trying out for a job himself. He tried to impart wisdom that went nowhere. The players kept making the same mistakes. They were beyond his help. He came back to the line and shook his head.

“These guys don’t listen. You have to be able to take direction. That’s part of it.”

As we watched, I approached Donovan “Captain” Morgan, one of the best receivers in the game, and asked him what he saw.

“Not much, you know. I’m waiting for the one-on-ones.”

“That’s when you can really tell?” I asked.

He nodded. These were the skirmishes within the battle that won the war. It was a one-on-one kind of league.

“It seems like guys are doing too much here,” I offered, “trying to do cone drills while they’re running routes.”

“Yeah,” said Donovan. “What is it? K.I.S.S.? Keep it simple stupid?”

“Yeah, KISS, exactly,” I said.

We turned back to watch the field. Then he turned to me, before he motioned to some other players as they watched.

“This is Neal. I haven’t quite decided if he’s a spy or not.” They laughed. Then I laughed uncomfortably, feeling very much the new kid. “Hey, has anyone ever told you look like Matt Leinart? Or like a baby Nate?”

Some of the other players looked at me.

“Yo, doesn’t he look like a baby Nate, or like Matt Leinart?” he persisted.

“Why?” I asked. “Is it because of my three-day growth and out-of-shape-volleyball-player body?”

While I appreciated all the quarterbacks I seemed to remind people of, it began to feel less and less like a good thing. But at least they didn’t think I looked like a kicker.

Another whistle blew, and the defensive backs were called over for one-on-ones. This is where the real fun started and everyone came alive. The setup was simple. The receiver told the quarterback what route he’d run, and then he’d try to run it against a defensive back.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/JwfrVVUxNr4&w=650&h=433]

The thin emperor who showed up with his two guard moms was the surprise star. Despite a gait that made him look like he was powered by the steam engine of an antique train, he beat his opponent every time. He looked outmanned as he leapt off the line. But then, miraculously, he would stride past his defender, catch the ball and amble toward the end zone with something resembling grace. Every time he did, the entire sideline would erupt in shouts of disbelief. It was like we all witnessed a feat of magic whose trick we couldn’t figure out, despite watching over and over again in search of the tell.

A small, soft-spoken wide receiver approached Coach Skinny and tapped him on the shoulder.

“What should I run coach?” he asked.

“What do you think you should run?”

He thought for a moment.

“A fade?” he asked.

Coach Skinny nodded and said, solemnly, “Use your ability, be impressive.”

He was jammed at the line. So was the next guy. In fact, you could see some of the defensive backs licking their chops when they went up against a smaller guy. They’d line up right at the line and wrestle the receiver at the spot and destroy the route. Other times they’d give too much space, about eight to 10 yards.

I found Terrance Smith, who had been a star on both sides of the ball for the Jacksonville Sharks, and asked him how to beat a defensive back when he gives you that much space. He looked at me the way a hawk eyes a field mouse, then broke into a smile.

“It’s simple,” he said. “I run right at ’em, and I let them decide.”

“Really?” I asked. “What then?”

“They don’t know what to do man! It freaks them out. Trust me, I’ve played both sides.”

“This is Arena,” Coach Omarr said. “Just because you think you can play football, doesn’t mean you can play Arena Football.”

At noon a final whistle blew and the tryout was called to a close. Everyone was beckoned back into the huddle. Coach Omarr thanked them for a good day. Then he spoke of what was next.

“Some of you guys, we’ll be in touch,” he said. “Others, thank you very much.”

Every player to a man felt that it was he who had been thanked. In the silence that followed, Omarr searched for what to say next.

“Conditioning… Some of you guys are out shape. You gotta be ready. Also, this is the Arena League. If you’re serious, learn the game. This is Arena, and just because you think you can play football, doesn’t mean you can play Arena Football.”

His emphasis on “arena” sounded ominous as hell. But the more I thought about it, the more it made sense. This isn’t football as America knows it. It’s eight-on-eight, on a 50-yard field, with walls lining the sidelines, nets in the end zones, and scores resembling college basketball games. The quick choppy routes, the high motion receiver—all the nuances amounted to a different brand of football. But these were things that I, like these men at the tryout, did not know. I had much to learn about this game.

With that deadly thank you and a “1, 2, 3, hard work,” they were released. A representative from the team informed them that if they showed their tryout T-shirt at the Tilted Kilt—a Celtic-themed sports bar known for short kilts the way Hooters is known for, ahem, owls—they’d get 25% off their meal, but today only. Some walked toward their cars, defeated. Others swarmed Coach Omarr, desperate to show him taped proof of their best, or to simply see if there was anything else they could do. One by one they left the field, until finally it was empty and quiet.

Afterwards, I caught up with Omarr along the sideline and I asked him if he’d found anyone.

He shook his head.

“No one that can help us.”

I noticed he kept his distance. He leaned on his back foot. I felt as if I had done something wrong. Maybe he decided he didn’t want this actor/model/writer/QB-look-alike around anymore. Perhaps it was my imagination, but he looked like he’d never wanted to be further away from another human being in his life. Instinctively, I tried to recover.

“So what do I need to do between now and the open tryout in February?” I asked him. “You know, in order to make the team?”

He fixed me with a stone gaze.

“Nothing,” he said. “Either you got it or you don’t.”

• Question? Comment? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com