Significance of contradicting accounts from Manning, Naughright

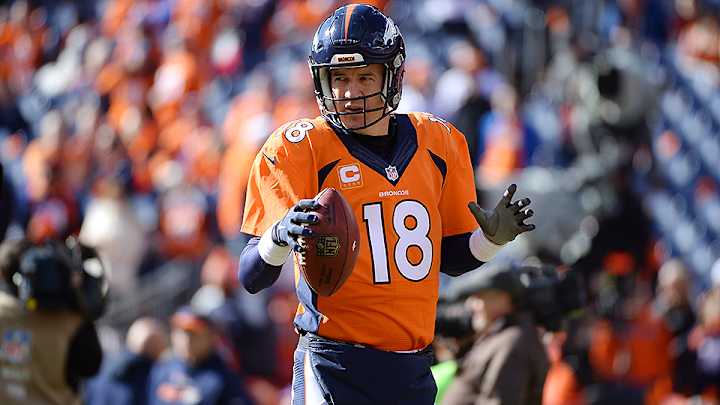

WATE-TV (Knoxville, Tenn.) has obtained and posted Peyton Manning’s affidavit that was filed in a Polk County, Fla. trial court on Oct. 3, 2003. The affidavit was in connection with Dr. Jamie Naughright’s defamation lawsuit against him, Archie Manning and ghostwriter John Underwood (a former Sports Illustrated writer, though he was not with the magazine then) over their book Manning: A Father, His Sons, and a Football Legacy. The affidavit was one of several hundred filings in a litigation that spanned from 2002 to ’05 and included two lawsuits filed by Naughright against Peyton Manning and one filed by Manning against Naughright.

Earlier this week, SI.com obtained and analyzed a number of documents in the litigation, which at its core centered on a disputed incident from Feb. 29, 1996 that involved a then 19-year-old Manning and a 27-year-old Naughright and that Manning discussed in the book. In a light most supportive of Manning, he briefly mooned another University of Tennessee football player, Malcolm Saxon, while Naughright examined his foot for a possible injury. In a light most supportive of Naughright, Manning intentionally and without Naughright’s consent placed his rectum and genitals on her face and then laughed about it. As discussed earlier this week, Naughright’s account appeared to worsen (or, she might argue, increased in detail) over the years.

The SI Extra Newsletter Get the best of Sports Illustrated delivered right to your inbox

Subscribe

Significance of Manning and Naughright offering contradicting sworn testimony

Manning’s affidavit is a very different document from his book. The core difference is that an affidavit contains written statements that are made while under penalty of perjury, while depictions in a book are not made under oath. A person who knowingly lies in an affidavit can therefore be charged with perjury, which is a felony, whereas a person who knowingly lies in a book cannot. As a result, Manning’s affidavit is a more reliable account since he would have risked the possibility of being charged with a felony by knowingly lying.

At that same time, Naughright provided her own sworn testimony, subject to the very same threat of perjury charges. Some of her testimony occurred in a deposition, which is similar to an affidavit in that both consist of sworn testimony. Deposition statements, however, are made orally and transcribed by an authorized court reporter.

Breaking down sexual assault allegations against Peyton Manning

Manning and Naughright’s sworn accounts are inconsistent with one another, which suggests that one or both of them lied or misremembered what took place in 1996. While Naughright recalled Manning making unwanted physical contact with her and laughing about it, Manning does not. On the third page of his affidavit, Manning recalled Naughright moving behind him to examine his foot while he spoke with Saxon, who was some distance behind Manning and Naughright. Manning claimed that Saxon then made a joke about Manning’s girlfriend (now wife, Ashley), which prompted Manning to briefly moon Saxon. “My shorts were never down farther than exposing my buttocks,” Manning declared. “I did not pull them down to my ankles.” Manning’s denial in his sworn testimony is consistent with his portrayal of the incident in his book, where he acknowledged that his behavior was “inappropriate” and “out of line” but stressed that it was lawful.

Saxon—the player whom Manning says he mooned—has altered his account of the incident, which raises questions about which version ought to be believed. While court records indicate that Saxon supported Manning’s depiction for several years, he appeared to have a change of heart by Dec. 10, 2002. On that date he wrote Manning a letter saying that he no longer agreed with Manning’s portrayal of the incident. In the letter, Saxon insisted that it was “definitely inappropriate” for Manning to have “dropped [his] drawers.”

Further, Saxon opined that Manning had “messed up” and urged Manning to “take some personal responsibility.” Saxon, however, did not clarify which aspects of Manning’s portrayal he no longer supported. Saxon also did not say or imply that Manning had made physical contact with Naughright. If anything, Saxon’s letter seemed factually consistent with Manning’s accounts—some sort of “mooning” occurred—although Saxon was more critical of Manning than Manning himself.

(SI.com reached out to Saxon this week but he declined comment.)

A 20-year-old incident won’t be re-litigated

So what really happened between Manning and Naughright in 1996? Only three people were there, and they all seem to remember it differently. The legal system is not going to clarify the matter. Manning and Naughright settled their dispute in 2005. While their settlement agreement has not surfaced, it likely contained non-disclosure provisions that will bar them from publicly talking about the incident for the remainder of their lives. Saxon, for his part, presumably could talk about the incident. He does not appear to be a party in any settlement agreement. Whether Saxon would want to is another story. Also, because Saxon has altered his version of the incident, his believability would be questioned.

New details revealed in Manning litigation with ex-Tennessee trainer

The police are also not going to investigate whether Manning assaulted Naughright in 1996 or whether one or both of them committed perjury over a decade ago. In fact, there is no indication that a law enforcement investigation took place in ’96. Even if the police wanted to investigate, the statute of limitations for any potential criminal charges have long since passed.

The only possible way the incident could resurface in court is if a Title IX lawsuit recently filed against the University of Tennessee raises it. The complaint in that lawsuit referenced the 1996 incident. The odds of Manning having to testify in the Title IX lawsuit, however, are extremely slim. The case could settle long before any former players are asked to testify. Even without a settlement, Manning’s attorneys would aggressively oppose any involvement of their client. They would stress that the ’96 incident is well beyond the scope of the statute of limitations for claims against the University of Tennessee.

Some disputed incidents forever remain so. The 1996 incident between Manning and Naughright will be one such notable example.

SI legal analyst Michael McCann is a Massachusetts attorney and the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire School of Law.

Michael McCann is a legal analyst and writer for Sports Illustrated and the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute (SELI) at the University of New Hampshire School of Law, where he is also a tenured professor of law.