A Legend and his Daughter’s Legacy

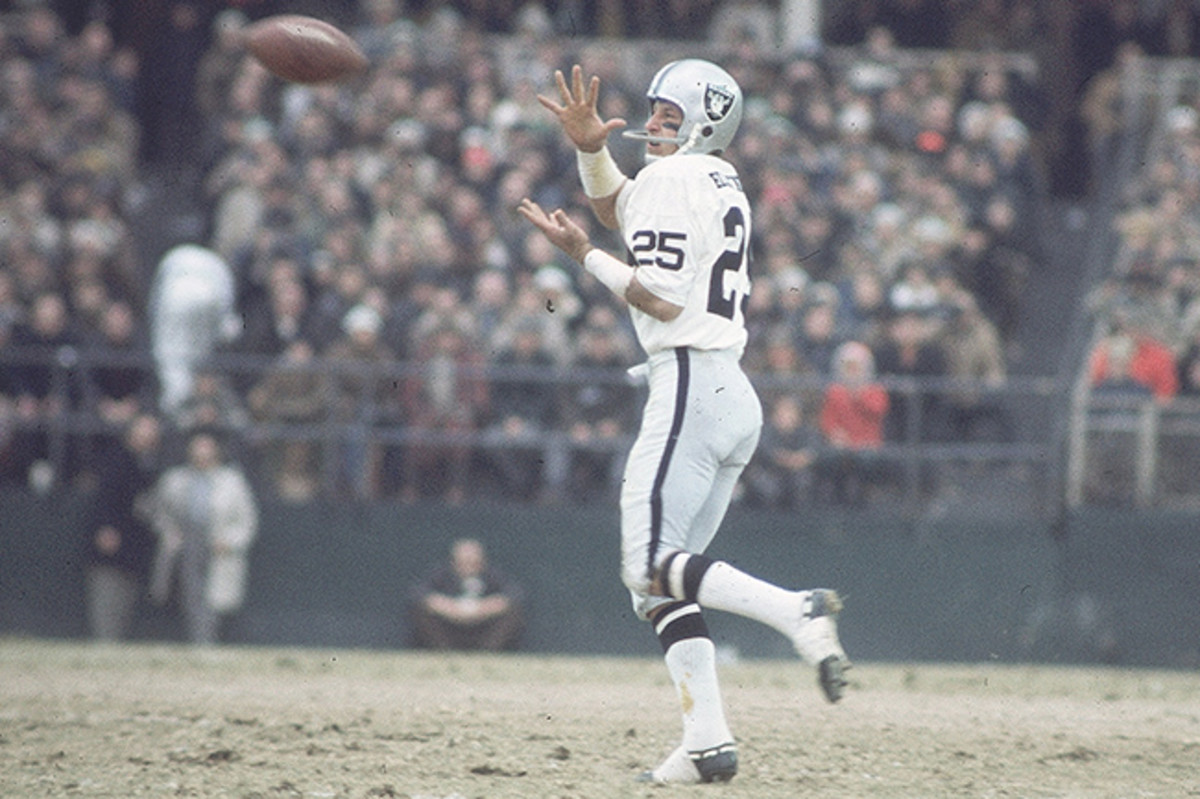

LOOMIS, Calif. — In the pageantry before Super Bowl 50, the game’s former MVPs paraded into Levi’s Stadium. Among the biggest roars were for 72-year-old Fred Biletnikoff, the Hall of Fame receiver who led Oakland to its first championship. Aided by a cane, Biletnikoff waved to the crowd as wind whisked his silvery hair.

Three days later, Biletnikoff is in a shrubby Sacramento suburb standing in a soon-to-be living room of a half-constructed house. A van pulls up and six teenage girls pour out. Each of them was born more than a decade after Biletnikoff played his final NFL snap; still they squeal upon seeing the former Raiders star. “Fred!” one girl says, barreling toward the right knee he had surgically repaired two months earlier. She gives him a hug. “Hiiiii!” two others shout.

“Well hi, ladies” Biletnikoff says, chuckling, as they gather on the freshly sanded floorboards. “It’s so great to welcome you all here.”

The teenage girls tour the shell of a home, which they will move into once it’s finished. “This is amazing,” says 16-year-old Rosie Guerrero.

“There’s going to be outlets in the bathroom?” asks 16-year-old Yesenia Ochoa. “So two of us can blow-dry our hair at once?”

“And a kitchen more than one of us can use at once!” Guerrero says. “The home we’re in now, it’s nice, but nothing like this.” She grins as she peeks at the backyard.

Each smile feels personal for Biletnikoff: They remind him of his daughter, Tracey.

“The Super Bowl introduction was flattering,” he says later. “But really, this is when I am most humbled.”

“What we’re doing here is personal,” Biletnikoff says. “If we get to them, it’s worth it.”

Tracey Biletnikoff was born in 1978, the year Fred retired from the NFL after a career that included six Pro Bowls and an MVP performance in Super Bowl XI.

In 1999, Tracey was murdered, her body discovered lying in a ravine. Her death was mourned by the Bay Area. She grew up with a famous father and as such, her life and struggles were oft publicized. Tracey used crystal meth, then heroin, and by 18 had checked herself into rehab. She fought her addictions until age 20, when the family says she turned a corner. She was clean, and began working as a drug counselor for teens. An ex-boyfriend whom she had met in rehab told her about a relapse, leading to a fight. Mohammed Haroon Ali strangled Tracey, then dumped her body. He is serving a 55-year sentence for first-degree murder after being convicted a second time in 2009 (the first conviction was overturned by an appellate court).

“The moment I heard that Tracey passed, I walked into the other room, and I spoke to her,” says Fred’s wife, Angela, Tracey’s stepmother, “I said, ‘Tracey, we will never, ever forget your spirit. We will continue your story. We will continue your life’s dream.’ I made a promise to her then, and that was an important promise. This is us continuing that vow.”

The new house will be called Tracey’s Place of Hope. It’s a $500,000 project, funded by the Biletnikoff Foundation and by Fred’s celebrity. Raiders owner Mark Davis wrote a $50,000 check last year; others donated their services (the electrician, for example, worked pro bono).

The residents have all battled substance abuse. They grew up in far corners of Northern California; some have been homeless, some physically abused. Most have been arrested, and because of their age, the state is willing to pay for their treatment. A court has mandated that each of them participates in programs run by Koinonia Family Services, an agency that partnered with the Biletnikoffs. Koinonia has five homes in Northern California; the Biletnikoff’s are helping upgrade their facilities, including Tracey’s Place of Hope.

Residents typically stay 12 to 15 months, although they can leave at any time (and some do). The goal is to keep them long enough for the program to resonate. The girls have chores and 10:00 bed times. They are bussed to an alternative high school during the day where algebra classes are intermixed with therapy sessions. At night they attend Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous meetings. On Saturdays they go to Cross Fit and on Sunday’s, church. Every few weeks, Biletnikoff comes in to tell stories. He says how lucky they are to have each other: When Tracey first entered rehab at 18, she was the youngest by nearly a decade. Programs for adolescent girls, like this one, didn’t exist.

He also tells them about the choices Tracey made, about weighing influences and relationships. “When I first heard him talk about Tracey,” Guerrero says, “I could relate. I thought about my own choices, about the people in my life and what path I wanted.”

In many ways, Biletnikoff is the NFL’s most prominent domestic violence advocate. But the he doesn’t want anything to do with the league’s effort to eradicate what has become a hot-button issue. He has never served as a consultant, never appeared in an official capacity.

“I think they have their own people in place, and that’s fine,” Biletnikoff says. “Because what we’re doing here is personal. We speak to a few girls, but we really speak to them. If we get to them, it’s worth it.” Biletnikoff boasts the Raiders were undefeated in games the girls attended last fall (2-0). He is just as proud to talk about Guerrero’s upcoming high school graduation, which he and Angela will attend.

A few feet away, Ochoa listens in. She has only been with Koinonia for a month. Before that, she was in jail and before that, she lived on the streets of Sacramento. She hated her first few nights at the shelter; the rigidness, the structure. She resented being around other girls. Behind her pink lipstick and leopard-print hoodie, she’s a tomboy. “Always been around guys,” she says. “Growing up, on the streets, everywhere.” She thought about running, and about what busses might take her back to Sacramento. “But after a week or so, it’s not that bad,” she says. “Plus if I stay here, I think I can get my degree.”

She watches Biletnikoff out of the corner of her eye. She wants to say hello, but she’s shy.

After a few minutes of trepidation, she introduces herself. “I’m a really big Raiders fan,” she gushes.

“That’s very nice of you,” Biletnikoff says. “But I bet you don’t remember me playing.”

She blushes. Soon, conversation floods. Ochoa tells him about how she was just three months old when she emigrated from Mexico and how she dreams of being a nurse in the Navy. “I hear that they are always looking for people who are bilingual,” she says. “So I think I have a shot.”

“Do you know what?” Biletnikoff says. “You’re going to be a great nurse one day.”