Skirting the Salary Cap, Franchise Tag Time, and Combine Fact and Fiction

First, a note of sincere thanks to so many of you who reached out to me through Twitter or otherwise about the loss of my father. Larry Brandt was simply the best guy I knew. He was as honest, ethical and selfless as the day is long. He was 88 years old, as tough as a two-dollar steak, and had a vice-grip handshake. Dad worked up to and including the day he went in for heart surgery. He was a homebuilder in Washington, D.C.—my memories of him are wearing a suit with construction boots, with a tireless work ethic that extended to all around him.

The summers I spent growing up as a $2-an-hour laborer on his job sites were the most educational experiences I ever had. So many friends and family relied on my father; he put everyone first and himself last; it was simply who he was. I miss him so much already.

Skirting the Cap

The news this week that the NFL was ruled to have underfunded the players’ share of the salary cap by $120 million pulls back the curtain on how the sausage is made at this time in calculating the cap.

Prior to the 2011 CBA, the players’ share—which climbed as high as 59%—was calculated based on Designated Gross Revenues (DGR), a formula with several carve-outs and exclusions for NFL revenues. Now the players’ share—hovering in a 46-48% band—is calculated from All Revenues (AR), with very limited exclusions. As it turns out, the NFL decided some of its ticket revenue they termed “waived gate” should be one of those limited exclusions. When conducting the annual accounting audit that happens every year at this time, the NFLPA discovered this discrepancy and, presumably rebuffed by the NFL toward inclusion, brought it to the league’s cap system arbitrator (unlike player conduct decisions, there is an independent arbitrator for cap decisions). He has quickly and decisively ruled that the NFL must include such monies in cap calculations, forcing the NFL to add approximately $120 million, or roughly $1.5 million per team, to the 2016 salary cap.

Although the NFL tried to minimize the discrepancy as “a technical accounting issue,” this is not a good look. As anyone paying attention knows, NFL owners are relentless negotiators not used to hearing the word “no” and seek every advantage possible. They have forged the most favorable economic system in major sports, with fixed and reasonable labor costs and contracts that shift the risk to the player after one or two years. This time, however, they were brushed back in their attempt to squeeze out another $50 million from the players. My sense, however, is that they will look at this slap on their wrist and shrug, as if to say “Well, we took a shot, why not?” and move on without remorse.

Game of Tag

The NFL’s annual two-week game of “tag”—allowing teams to apply the franchise or transition tag to players with expiring contracts to exclude them from free agency—began 10 days ago and ends on Monday. In a league where nothing happens without a deadline, no tags have been applied as of this writing, with all of them likely coming on the last day possible.

The tag, first introduced as the NFL entered the free agency era in 1993, was originally intended to be the NFL’s version of the NBA’s “Larry Bird Rule” and was supposed to ensure that true franchise-defining quarterbacks—at that time Dan Marino, John Elway, Troy Aikman, Brett Favre, etc.—would remain centerpieces of their franchises. Over time, however, the tag has morphed into a stronger tool, allowing teams to take their best free agent for the current year off the market, no matter the position. Indeed, the tag is now used far more for kickers—yes, kickers—than it is for quarterbacks.

Although I understand the NFLPA not pressing this issue more in CBA negotiations, using the rationale that it only affects a handful of players, I would argue that it affects dozens of current and future negotiations. Teams negotiating with Von Miller, Josh Norman, Kirk Cousins (more below) and several others can do so knowing they have the one-year placeholder of the tag in their back pocket. The number of negotiations involving the team’s real or perceived threat of using the tag for leverage is far more than what we know.

• WHO ARE YOU REALLY GETTING? Best and worst case scenarios for top free agents

Although no one is crying for him, a player like Von Miller, purportedly at the height of his negotiating leverage as a Super Bowl MVP, will never know his true market value. Further, all negotiations taking place at outside linebacker will now operate with parameters under the Miller parameters, ones artificially created by the tag. And whatever the type of contract these tagged players eventually receive, it will not be far less than the one they could have received had they been negotiating with 32 teams as a free agent instead of only negotiating with their incumbent team.

I know what people say: players are making a lot of money for their one-year of tag labor. However, players are like most employees; they want security. They would prefer the team “marry” them rather than continue to “date” them year-to-year.

Finally, I am surprised that the transition tag does not get more usage, especially as teams’ cap situations stabilize. I saw it as a valuable way to let the marketplace decide the value of the player—at a cheaper rate than the franchise tag—while retaining the right to match. I used it on a Packers tight end named Bubba Franks, a player for whom his agent and I had vastly different views on value. We decided to use the transition tag and let the marketplace decide. When Bubba did not receive an offer, we negotiated a contract knowing more than we knew before the tag period.

Paying Cousins

The Redskins probably made an “it doesn’t hurt to ask” opening offer to Kirk Cousins to see what would happen, probably in the Colin Kaepernick/ Andy Dalton range (two-years, $25 million and then “we’ll see.”) Insulted by such offer, Cousins’ team voiced its displeasure to the media, forcing the team to take Cousins more seriously. The goal—straight out of the negotiation handbook—was to create a level of angst among fans, media and perhaps the Redskins front office in needing to step up their game. Now the Redskins will scratch out a more aggressive proposal, knowing the tag is in their back pocket, like a coach’s challenge flag, and ready to be thrown on March 1.

What is the right number for Cousins? Beyond the illusory headline numbers of the total value, structure is the key. Cousins should be seeking a truly secure $55-60 million over the first three years no matter how he performs. The key to contract negotiations is risk allocation, and if Cousins can shift the risk to the Redskins for at least three years, he can be comfortable assuming the risk after that.

• WORRY FREE WASHINGTON: Peter King on why Washington fans shouldn't worry about Cousins

I still shake my head thinking that the Redskins are about to give a top-of-market extension to a quarterback taken in the same draft that they mortgaged the future to draft a different QB! I was wrong; I was convinced that Kirk Cousins was drafted to be traded. Now it is Robert Griffin who will be traded, while Cousins cashes in with the contract originally expected to go to Griffin. What fortunate circumstances for the Redskins, saved by an afterthought draft pick after such a big miss.

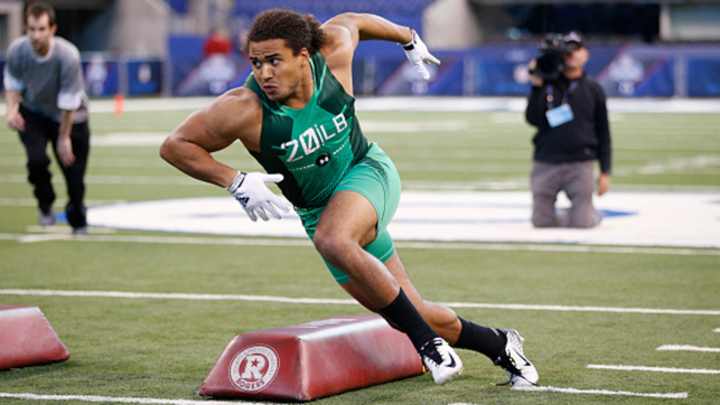

Combine Fact and Fiction

Fact: Tampering is alive and well at the combine. The largest single gathering of the year consisting of both player agents and team negotiators just happens to occur a week before the official start of free agency—what exactly does the NFL expect to happen? Agents are mapping out the options for their players once the free agency bell rings on March 9. (I remember once trying to meet with the agent for one of our pending free agents and he was too busy meeting with other teams to meet with me!) Of course, if agents and teams want plausible deniability, they usually have existing or former clients on the team that can be used as cover, if needed. As long as the NFL continues to schedule the combine right before the start of the new League Year, it will continue to be the functional start of NFL free agency.

Fiction: Combine results have dramatic impact. In truth, teams have largely set their draft board before arriving at the combine, having done so after months of grinding through visits and game tape. Combine numbers, for the vast majority of players, will largely confirm what they know. Sure, there will be outliers who move up or down a round or two based on their combine drills, but they are the exceptions, not the rule.

• THE NFL COMBINE AND YOU: Robert Mays on five themes present at the combine every year

Fact: Medical examinations matter. The combine is where team medical staffs can get their hands-on reads of player health. While a draining experience for the player to go through 32 medical examinations, it is a vital part of the evaluation process. Players will get a grade, usually on a scale of 1 to 4—from totally clean to a medical reject—and that grade will often be the difference when teams are on the clock if two players are rated equally.

Fiction: Interviews matter. Combine preparation has become such a big business that players are not only physically prepared but also mentally trained through repeated mock interviews. I found their answers—yes, we know you love your mother and are coachable—to be so scripted that they give no window into the player. Thus, I would always try to get them off script, asking questions such as, “If you were us looking to invest in you, tell us three things we should be concerned about?” I would also ask a lot about their routines and daily rituals, looking for evidence of self-discipline and self-motivation, two characteristics I have found most important in predicting success.

• Question or comment? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com