More than just smart guys: Harvard’s reputation growing in NFL

INDIANAPOLIS — Harvard football players are never just football players. They’re Harvard football players. They’re smart football players. They’re cure-cancer, run-for-president, my-classmate-created-a-billion-dollar-app football players.

Which isn’t necessarily the worst thing. Or necessarily the best thing. Take Ryan Fitzpatrick’s experience. Mostly good. Eleven-year NFL veteran. Thirty-one touchdown passes for the Jets in 2015. Harvard alum. Maybe you’ve heard? Smart guy. Went to Harvard.

But there is a stigma, and it started his rookie season. He played for the Rams in 2005 and ’06, and his teammates, fellow quarterbacks Gus Frerotte and Marc Bulger, decided to create a “Christmas card.” Create they did. There’s Fitzpatrick, in his crimson football jersey, wide smile, a trumpet photoshopped into one hand and a bouquet of flowers photoshopped into the other. “Happy holidays,” the card reads. “From the Harvard band.”

The worst part was that several Rams employees actually thanked Fitzpatrick for how thoughtful his card was. They thought it was, you know, not a prank.

The prevailing notion of Harvard’s gridiron prospects has changed in the decade since, as players from the school, like Fitzpatrick, have not only made the pros but reached various levels of NFL success. The thinking has gone from: smart kid, small chance, to: smart kid, real chance.

That culminated in Feb. 2016, when offensive lineman Cole Toner and tight end Ben Braunecker, two prospects out of Harvard, were invited to the NFL Scouting Combine. That’s the most Ivy League players invited in any one year from any one school. Ever. Oh, and that means there are more prospects invited this year from Harvard than from Texas.

“That’s a pretty cool stat,” Toner says. “It’s not an indictment of Texas for me. It’s just a really cool thing for Harvard. It’s a testament to the type of guys we recruit, the type of clout we have. It’s a legitimate program.”

Top QBs ward off their weak points as combine circus begins

Toner says this Wednesday evening, while reclined in an oversized chair in the Indiana Convention Center, in one final interview at the end of a long day. He’s used to all the Harvard jokes, the trash talk, the revenge-of-the-nerds headlines.

Those started before he even went to Harvard. He met Braunecker, another Indiana native, when they played in a high school football all-star game. Their teammates called them Harvard 1 and Harvard 2.

As the conversation with Toner meanders, he sometimes can sound very, shall we say, Harvard-ish. He’s not only trained for the combine with Braunecker at Indiana-based St. Vincent Sports Performance, the two have lived in the same room in the same dorm, the Harvard-sounding Cabot House, since they were sophomores in 2013. He describes their non-Harvard obsession—the video game Super Smash Bros.—but even then gives a very Harvard-y rundown. Of Braunecker, Toner says, “He’s technically the most sound at Smash Bros., if you can be technically sound at Smash Bros.”

He’s asked if people have the wrong idea about football at Harvard, where the Crimson went 9–1 last season and recorded 36 victories in his four seasons there. “People just don’t know,” he says. “It is frustrating a bit. I would say it’s a small percentage, but 10% of the kids there don’t think athletes should be in school at all. They don’t think we should have gotten into school. Do they come to games? Not necessarily.”

He continues, “We’re big men on campus in terms of stature. Not necessarily big men on campus in terms of fame.”

Size matters? QB Brandon Allen trying to make his hands bigger

That’s changing, though, and has been for a while now. It started, really, with Tim Murphy, who recently completed his 22nd season as Harvard’s football coach, or, as it’s officially called, The Thomas Stephenson Family Head Coach for Harvard Football. He’s won more games (156) than all but two Ivy League football coaches ever. He’s also won nine Ivy League championships, including a title in each of the past three seasons.

He doesn’t think smarts and sports have to be mutually exclusive. “When I came from Cincinnati in 1994, coming from a major program, people were like, ‘you’re crazy,’” Murphy says. “But I’ve never been around kids who were athletically more motivated.”

Toner and Braunecker are exactly the kinds of players Murphy looks for: under-recruited, multi-sport athletes. Toner graduated from Roncalli, a private, Catholic high school in south Indianapolis. He played baseball and basketball there, at least before he grew into a 6’7”, 300-plus-pound O-line prospect who made All-Ivy League first team each of the past two seasons.

MAAC schools showed some interest, as did Indiana and Cincinnati. But none of them made any offers. When Toner visited Harvard, he found “a blue-collar program.”

“You don’t really think of that in the Ivy League,” he admits. “But guys prioritized football as much as they did school.”

As a freshman, Toner started against Princeton, holding his own against two NFL prospects. That’s when the NFL seemed possible. “He has become exactly who we felt and hoped and thought he would be,” Murphy says. “A kid that could have played anywhere. A kid capable of playing in the NFL.”

That’s obviously not all Toner is capable of. He managed a 3.6 GPA while majoring in government with a minor in economics. He says he might get into politics one day. For the last two summers he interned at State Street Bank in Boston, in their legal and regulatory office. His boss last summer was a prominent lobbyist. He met congressmen. And while most of the top NFL prospects trained full time, Toner took four classes this spring: environmental economic policy; science of the physical universe; money, work and social life; and road to the White House.

His roommate, Braunecker, grew up in small-town Indiana, in a town called Ferdinand (with a population of roughly 2,000). What sold Murphy on Braunecker was his basketball prowess—last year he won Harvard’s team dunk competition with an alley-oop windmill—and the fact that in track and field, he put a shot more than 60 feet in high school. That, to Murphy, indicated explosiveness. So much so that his Harvard teammates nicknamed Braunecker “Bronk,” after Rob Gronkowski.

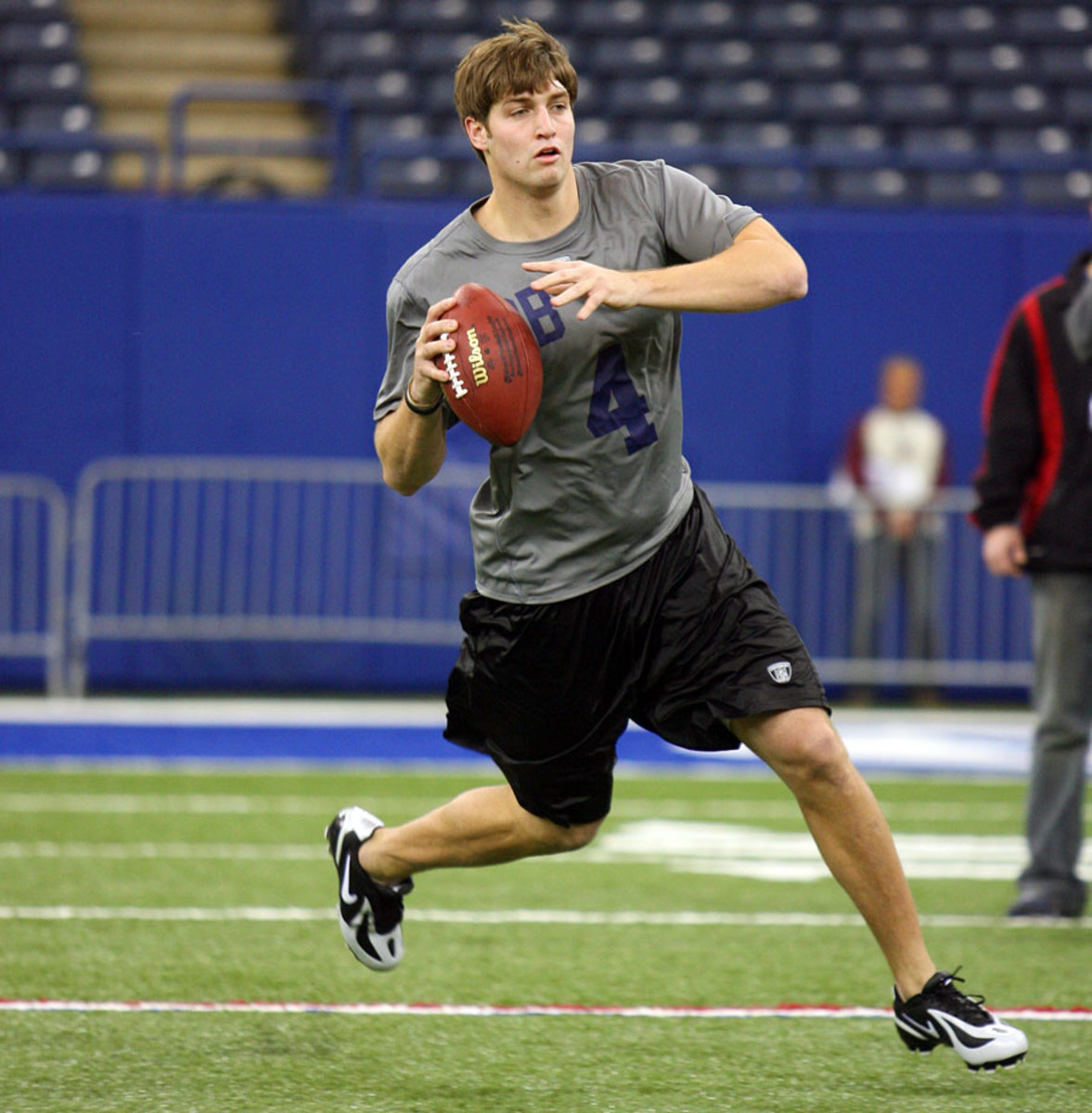

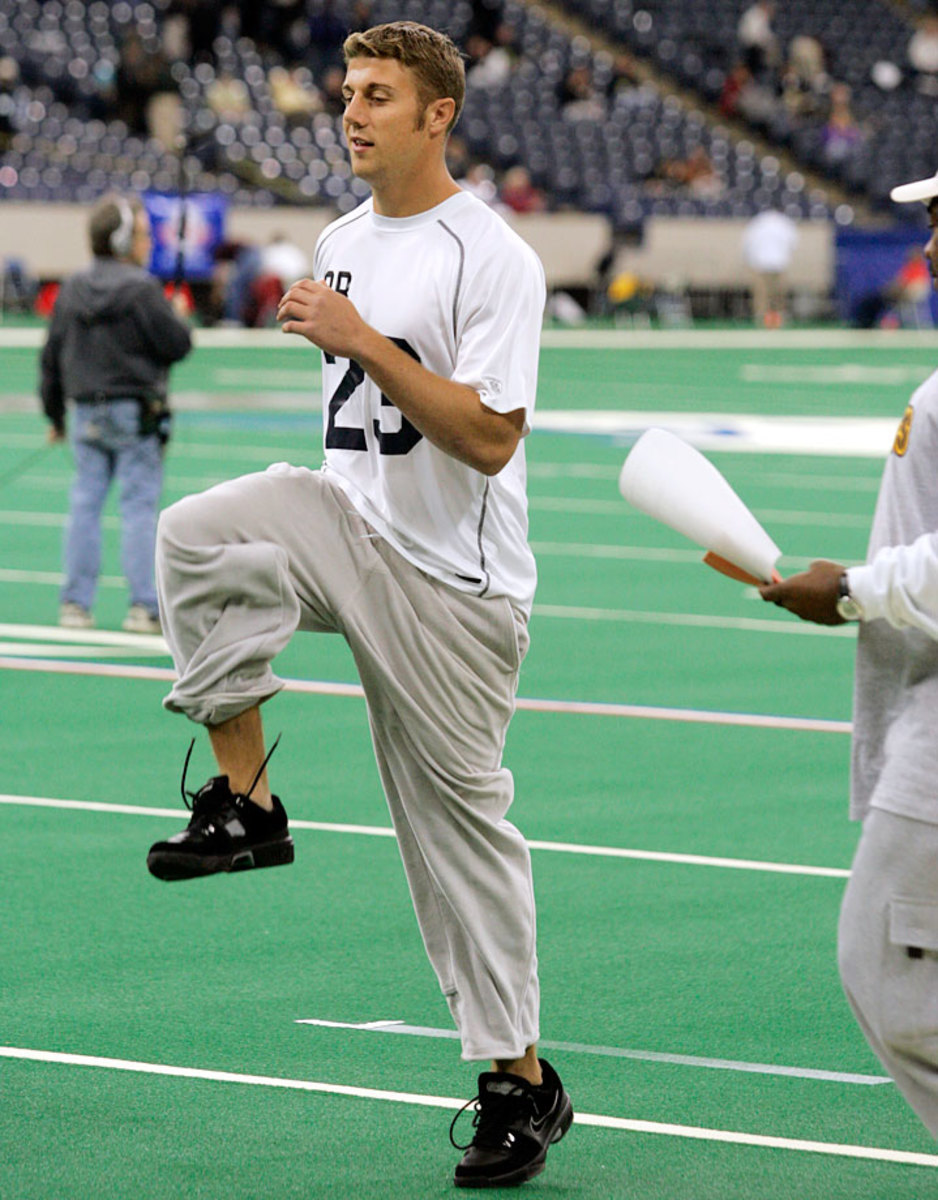

Classic SI Photos from the NFL Combine

2016

2016

Ronnie Stanley

2016

Bronson Kaufusi

2015

Todd Gurley

2015

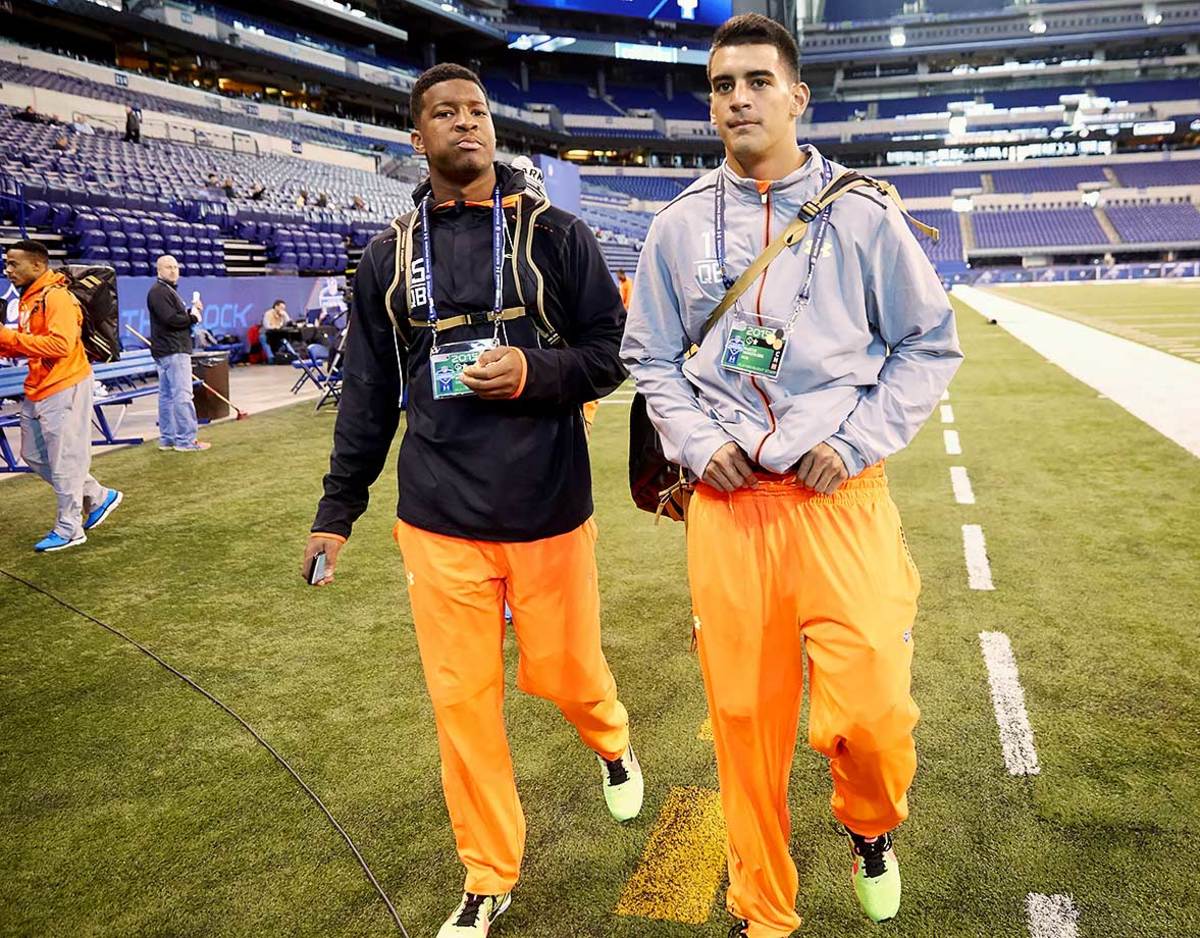

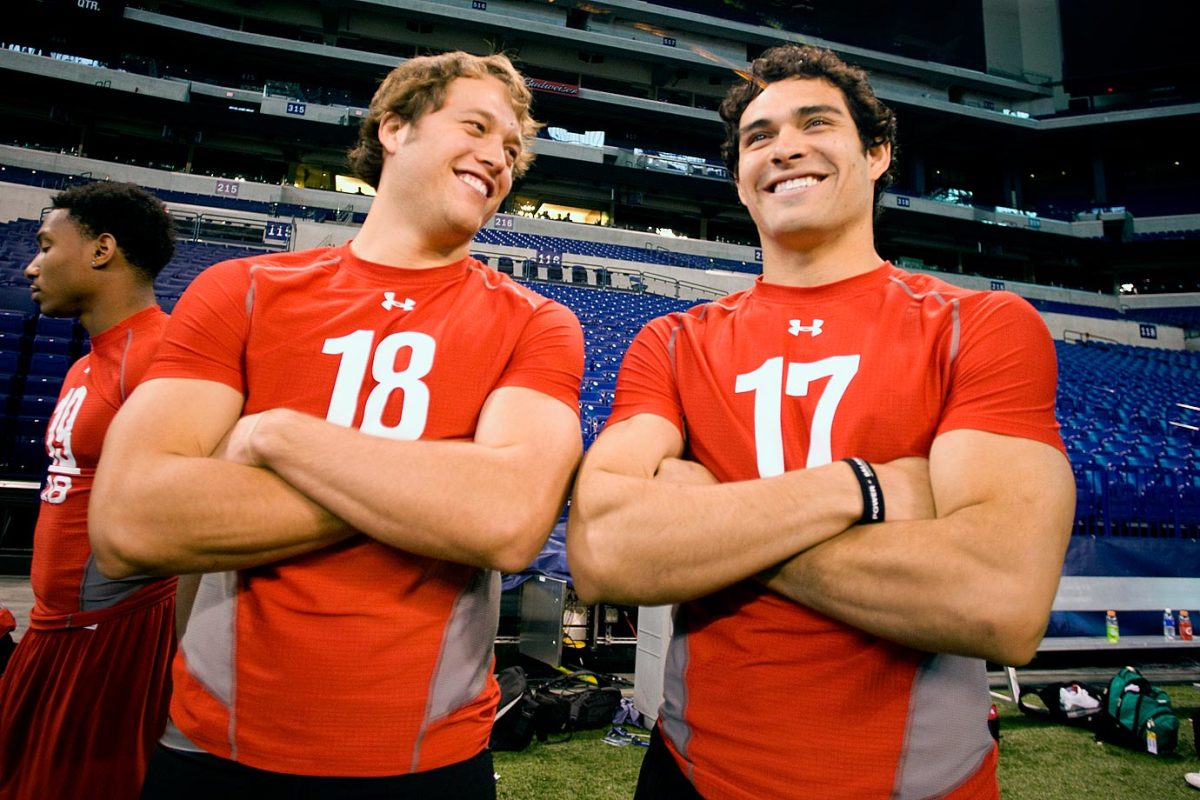

Jameis Winston and Marcus Mariota

2015

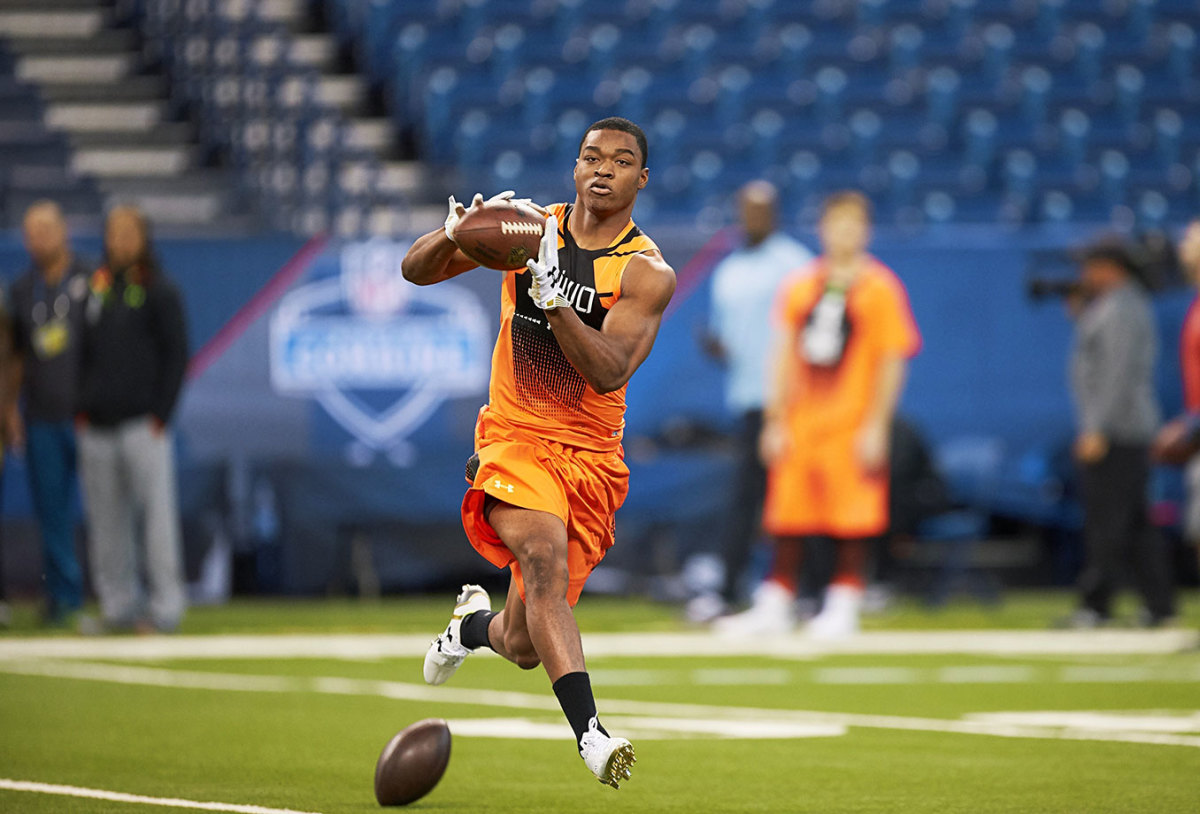

Amari Cooper

2015

Leonard Williams

2014

Jack Mewhort and Jake Matthews

2014

Johnny Manziel

2014

Andre Williams

2014

Jadeveon Clowney

2013

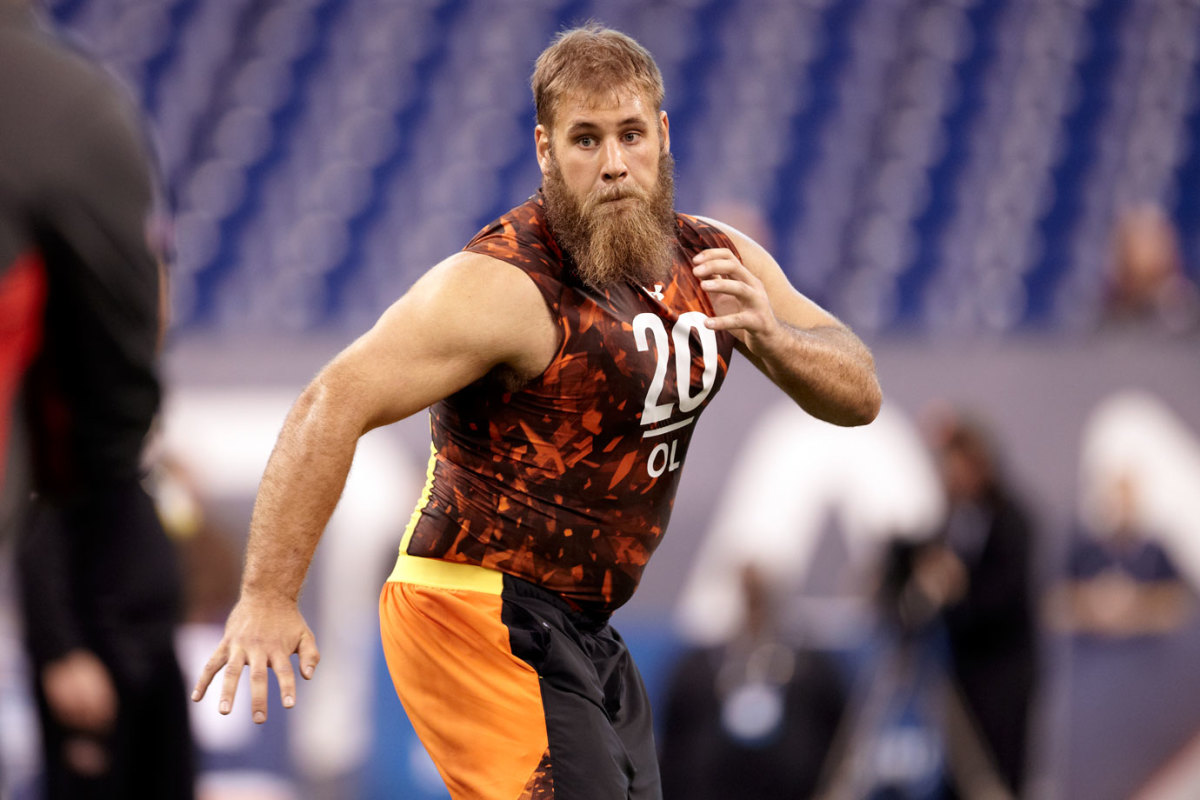

Travis Frederick

2013

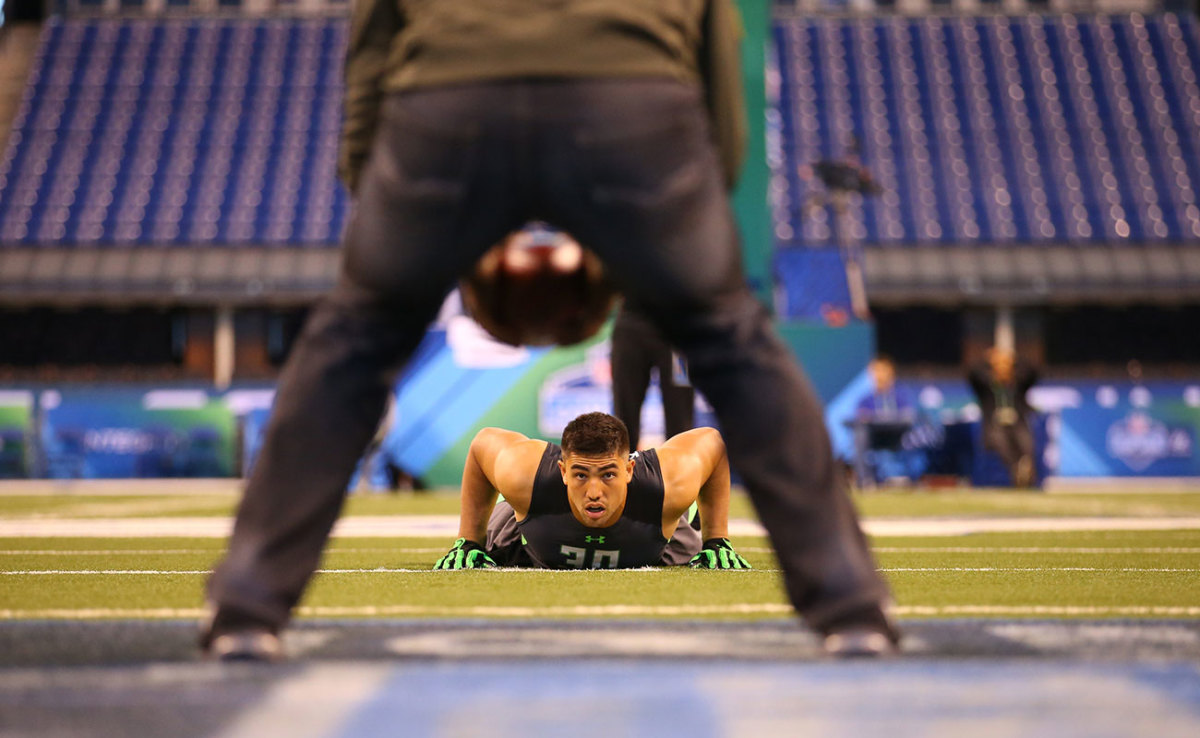

Luke Joeckel (27)

2013

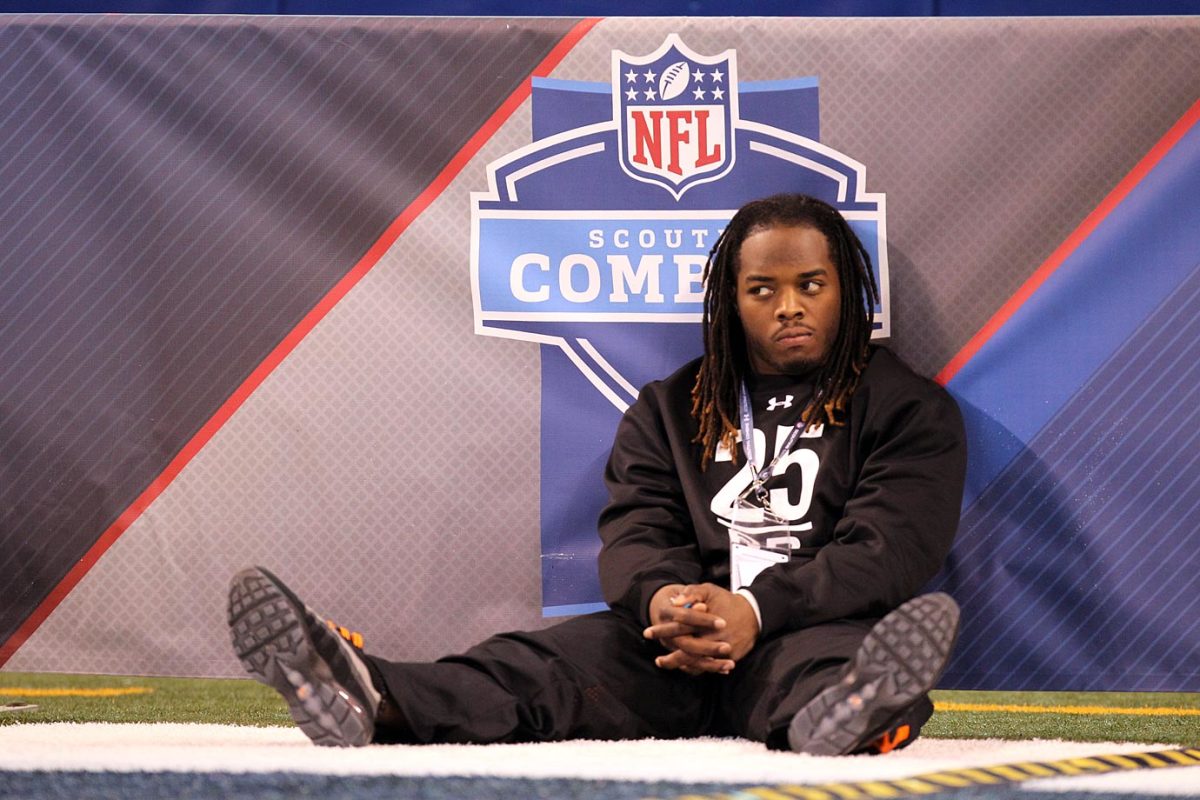

Manti Te'o

2012

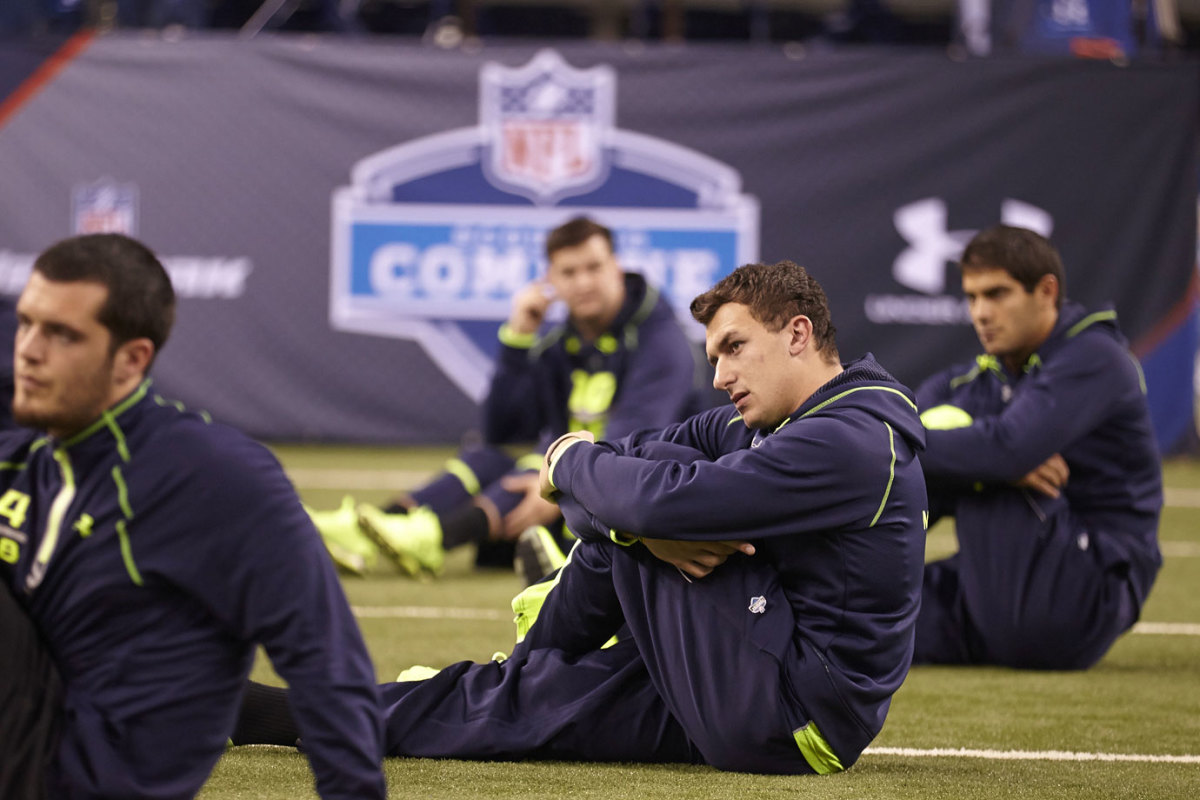

Ryan Tannehill, Andrew Luck and Russell Wilson

2012

Robert Griffin III

2012

Trent Richardson

2011

Cam Newton

2011

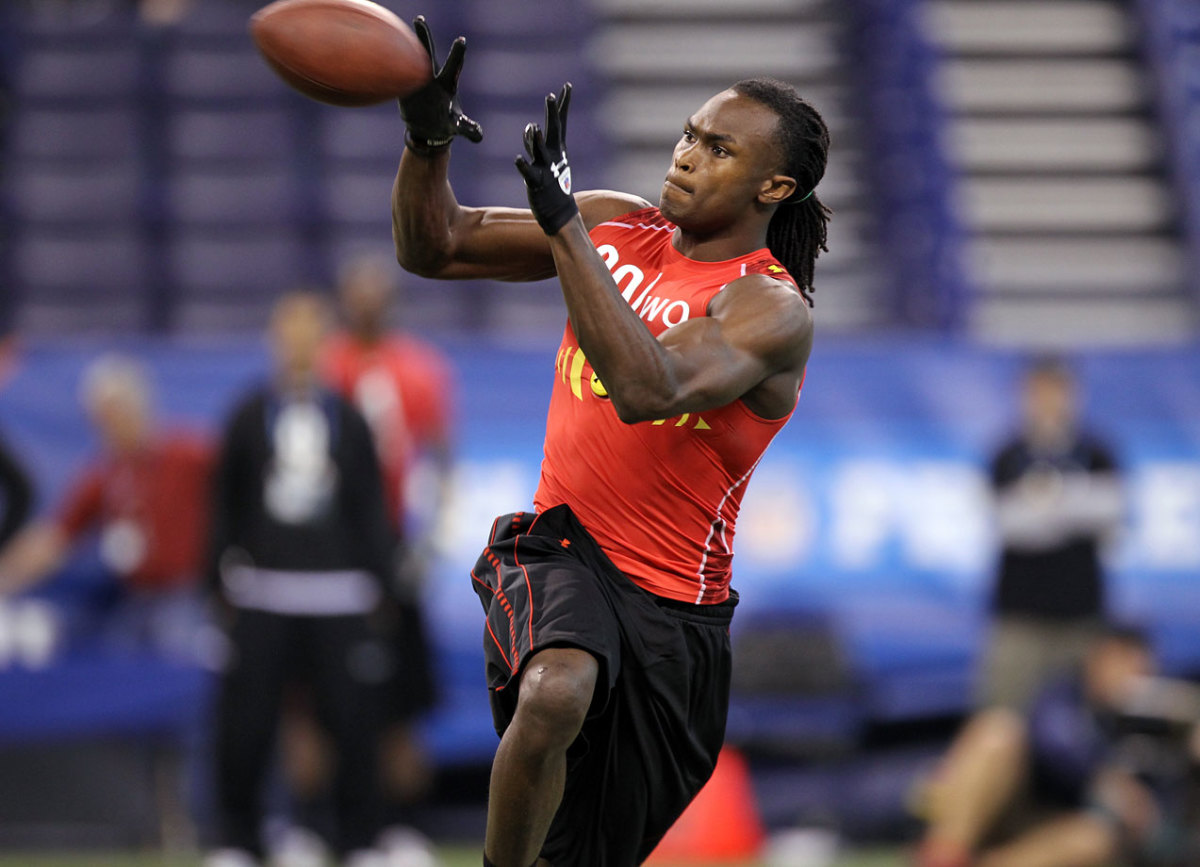

A.J. Green

2011

Julio Jones

2011

Von Miller

2010

Ndamukong Suh

2010

Tim Tebow

2010

Sam Bradford

2009

Matthew Stafford and Mark Sanchez

2009

Mike Wallace

2009

Michael Oher

2009

Beanie Wells

2008

Matt Ryan

2008

Jake Long

2008

Chris Johnson

2008

Tom Coughlin

2008

Peyton Hillis

2008

Darren McFadden

2007

Adrian Peterson

2007

Greg Olsen

2006

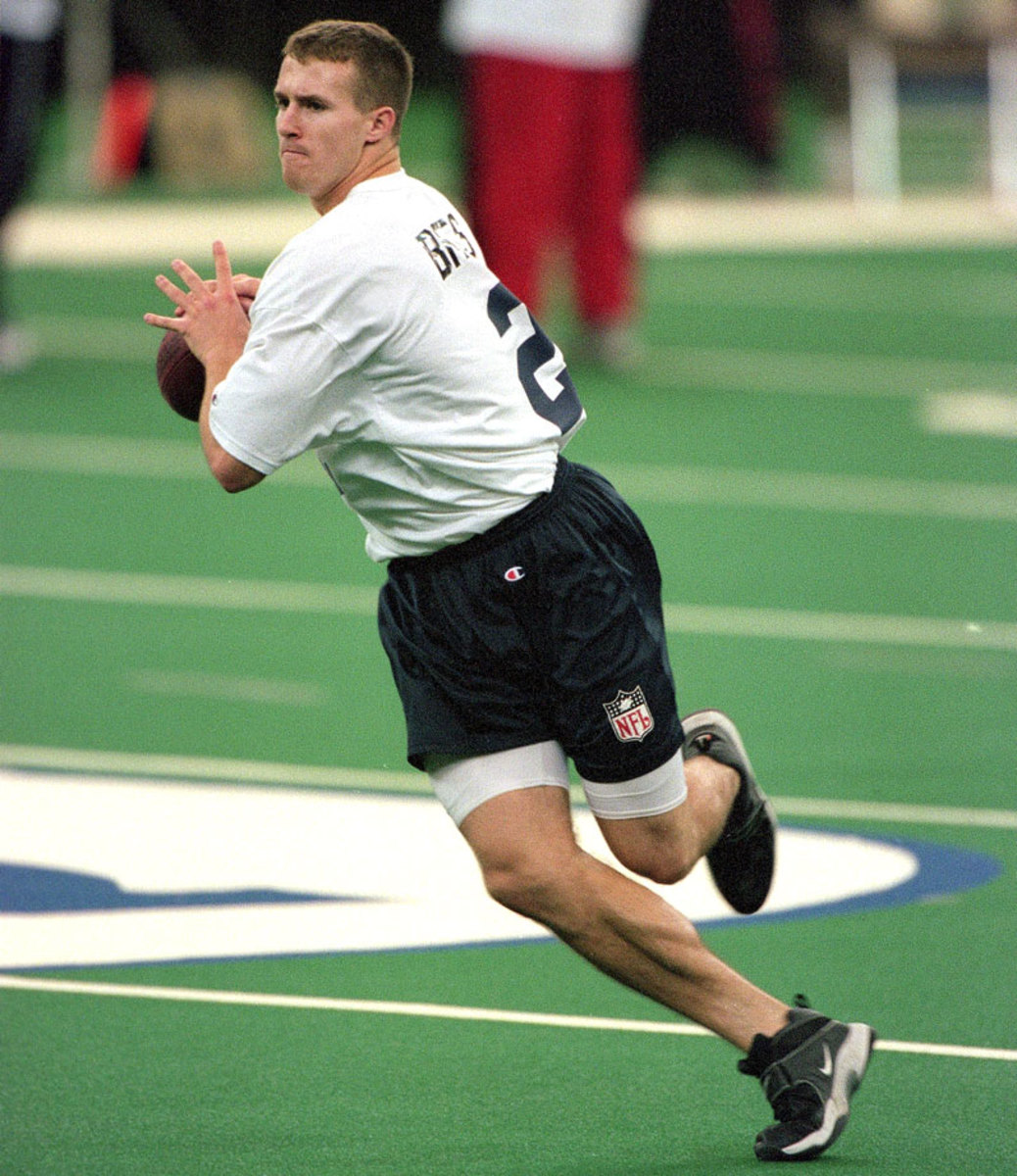

Jay Cutler

Despite an influx of innovations, many NFL teams are fiercely loyal to the old-school ways of measuring prospects, as Aaron Rodgers demonstrated at the 2005 combine.

2005

Alex Smith

2004

Ben Roethlisberger

2004

Steven Jackson and Chris Perry

2004

Robert Gallery

2001

Drew Brees

1995

Steve McNair

1995

Mike Holmgren, Bill Parcells and Buddy Ryan

1995

Kerry Collins

1995

Warren Sapp

Bronk’s major: molecular and cellular biology. One NFL team, he didn’t say which, asked him about the Zika virus in Brazil that’s been all over the news. “I’m not a doctor,” Bronk told them. But he hopes to be, perhaps on the research end, after an NFL career.

He’s the latest in a short but growing line of Harvard tight ends. There are three in the NFL right now: Cameron Brate (Tampa Bay), Tyler Ott (who is mainly the Giants long-snapper) and Kyle Juszczyk, a Raven who converted to fullback. Murphy says so many have stuck because “they’re the SEALs of our offensive unit,” in that they play wide receiver, slot receiver, tight end and fullback. They have to be versatile, tough.

That’s Murphy. Fitzpatrick notes that Murphy placed a national emphasis on recruiting at Harvard that had not been there before. Growing up in Arizona, Fitzpatrick didn’t even know that Harvard had a football program, until a recruitment letter arrived in the mail. Look at the Harvard players in the NFL, Fitzpatrick says. They’re from Minnesota, Toronto, North Carolina, New York.

When Fitzpatrick arrived at Harvard in 2001, the team didn’t have a strength coach. Now, under Murphy’s Law, they do. They also get his summer reading list recommendations before every football season. Last year’s included Gates of Fire the historical fiction novel by Steven Pressfield.

When Isaiah Kacyvenski graduated from Harvard in 2000, he was not invited to the combine. He had the Harvard coaches call teams that might be coming to the Boston area to scout Chris Hovan, a BC defensive lineman who the Vikings took in the first round. Kacyvenski did 14 mini-combines, one for each team that showed interest. The Seahawks took him in the fourth round. He played seven NFL seasons for three teams.

Elway has excelled in building Broncos for life after Manning

Teammates told him their high school teams could have beaten Harvard’s college squads. “At first, everyone expects you to know everything,” Kacyvenski says. “Every piece of trivia. Settle every debate. If you don’t know, they think that you’re a dumb---. The second thing is everyone thinks you’re rich and pompous and grew up with a silver spoon. Like, ‘Oh, he’s got a fallback plan.’”

Kacyvenski did have a fallback plan: become a doctor. But only after football, which is the same mindset Toner and Braunecker are carrying into this year's combine. “It takes guys like this to change the mindset,” Kacyvenski says. “I always tell them football is the great equalizer. If you can play, you can be smart, too.”

As long as Harvard 1 and Harvard 2 remember that, they can put it on their Christmas cards.