A Quixotic Bit of Foolery

Editor’s note: You may recognize Neal Bledsoe for his roles on The Mysteries of Laura or The Man in the High Castle, or for his stint as an Old Spice Man. You’ll soon be able to watch him as the leading man of his own TV show. Beyond acting, he’s an MMQB contributor chronicling his quest to make the Arena Football League. If you haven’t read it yet, catch up on his first story, “A Man, the Arena, and His First KISS of Fate,” then jump right into the second act...

Two Sports, Both of Them Football

Jan. 25, 1987

The Rose Bowl

Pasadena, Calif.

The New York Giants had just won Super Bowl XXI. The hog mollies of the offensive line hoisted Bill Parcels upon their shoulders and the Giants rushed the field. Flashbulbs popped. They slapped each other on the backs, giddy with excitement, and hollered with joy. “New York, New York” blared through the loudspeakers like triumphant trumpets. It was their first title since 1956.

The victory was even sweeter for quarterback Phil Simms. He connected on 22 of 25 of his passes, good for a then NFL postseason record of 88%. He threw three touchdowns, no interceptions and had John Madden in fits of hyperbole, proclaiming that you could now put him among the game’s elite. He was named MVP. It had not been an easy road, but after eight years of boos, benches and injuries, it was finally his time to celebrate.

In the midst of the celebration a Disney camera crew found him and tapped him on the shoulder.

“Phil Simms, you’ve just won the Super Bowl. What are you doing next?”

“I’m gonna go to Disney World,” he beamed.[1]

Every season since, while the theme music of Pinocchio plays sweetly above castles and fireworks, Super Bowl heroes proclaim to the world that they are going to Disney World or Disneyland (they film a commercial for each coast).[2] This simple phrase has become shorthand for winning the Super Bowl. It has even transcended football to seed itself in our pop-vocabulary, where—and I’m sure this was Disney’s aim—it has become synonymous with dreams coming true.

Under the bright lights of the Rose Bowl, with more than a hundred thousand people packed into its stands, and more than a hundred million watching at home, a uniquely American tradition was born.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8P-gDZmFnTQ&w=650&h=433]

June 19, 1987

Pittsburgh Civic Arena

Pittsburgh, Pa.

Just a few months later another game was played. Under the stainless steel dome of the old Pittsburgh Civic Arena, some 12,000 curious and football hungry fans came to see the Pittsburgh Gladiators face the Washington Commandos. It was the first official game of the Arena Football League. These fans hadn’t seen anything like it. Football indoors. On a half-sized Astroturf field. Padded walls on the perimeter like ice hockey. A decidedly roller derby vibe. It was pure Americana.

In contrast to the Super Bowl, this game was deliberately kept off television. Even the creators of this new league didn’t know what it would be yet. Until the wrinkles had been ironed out, there was a fear of becoming a laughingstock.

That night, with thousands of unsold tickets and no TV coverage whatsoever, Pittsburgh gutted out a 48-46 victory and the Arena Football League was born.

These two nights in 1987 give us the high and low ends of professional football: the game that everyone is watching, and the game of nobodies. One is the mountaintop, and the other is the valley below.

The Arena League is full of men at the cusp of the dream. They play with nothing to lose, confident that they are good enough to make the NFL. Some have already been there and are fighting to get back. Some have yet to go. Some just love to play. All of them would give everything for a chance to hoist the Lombardi Trophy and announce to the world that they’re going to Disneyland.

It is the longest of shots, but that’s the dream. So let’s get down to brass tacks. Has anyone ever done it?

Allow me to introduce you to Kurt Warner…

* * *

Between Those Hash Marks, I Felt Alive

“I think I was like all those guys you’re talking about,” Kurt Warner told me in a recent phone interview. “We all want to be the best, and we associate the best with something, and in football it was the NFL. That was always the dream.”

Most know Warner from his time orchestrating the Rams’ Greatest Show on Turf. Many know his journey, his humble beginnings and his triumphant climb to the top of the NFL. I asked him to recount his footsteps and he was kind enough to walk me through it.

In 1994, Warner was brought in as a rookie to be the fourth quarterback at the Packers’ minicamp. Ahead of him on the depth chart was Heisman winner Ty Detmer, future three-time Pro Bowler Mark Brunell and future Hall of Famer Brett Favre. The undrafted free agent out of Northern Iowa was like a fourth wheel on a tricycle.

“My second day, coach asked me to go in and play. I refused because I didn’t feel comfortable with what I was doing,” he said. “I had the mindset, If I don’t go in and mess up, then I can’t give them a reason not to keep me. Shortly after that I was cut. A guy playing that position who was afraid to make a mistake was not a guy they wanted leading their team.”

He looked everywhere for another opportunity. He called Canada and NFL Europe. No one wanted him. Then the AFL called him.

“The only time I ever saw it was in the middle of the night when I happened to be flipping through sports channels on TV,” he said.

He felt above it, but it was his only opportunity. He signed with the Iowa Barnstormers. “Just go play football,” he told himself. “It’s what you love to do. It’s what you believe you’re supposed to do. Go play football.”

His first taste of the preseason was a disaster. Things were so fast and the field was so small that the game he once thought himself too good for overwhelmed him. “I remember thinking, I don’t know if I can play this game. It just seemed like a big blur.”

He got better. A lot better. The things he wasn’t sure he could do early on—pinpoint accuracy and lightning-quick decision-making—became the hallmarks of his game.

“Arena football is like a two-minute drill the entire game. You’re expectation is you have to score every time you touch the football. I don’t know if you could be under any more pressure as a quarterback than you are in Arena football. The place I thought was the worst place for me to go was the ultimate training ground for me to develop into the quarterback I would become.”

I asked him if he ever said the Disneyland line to himself as a kid.

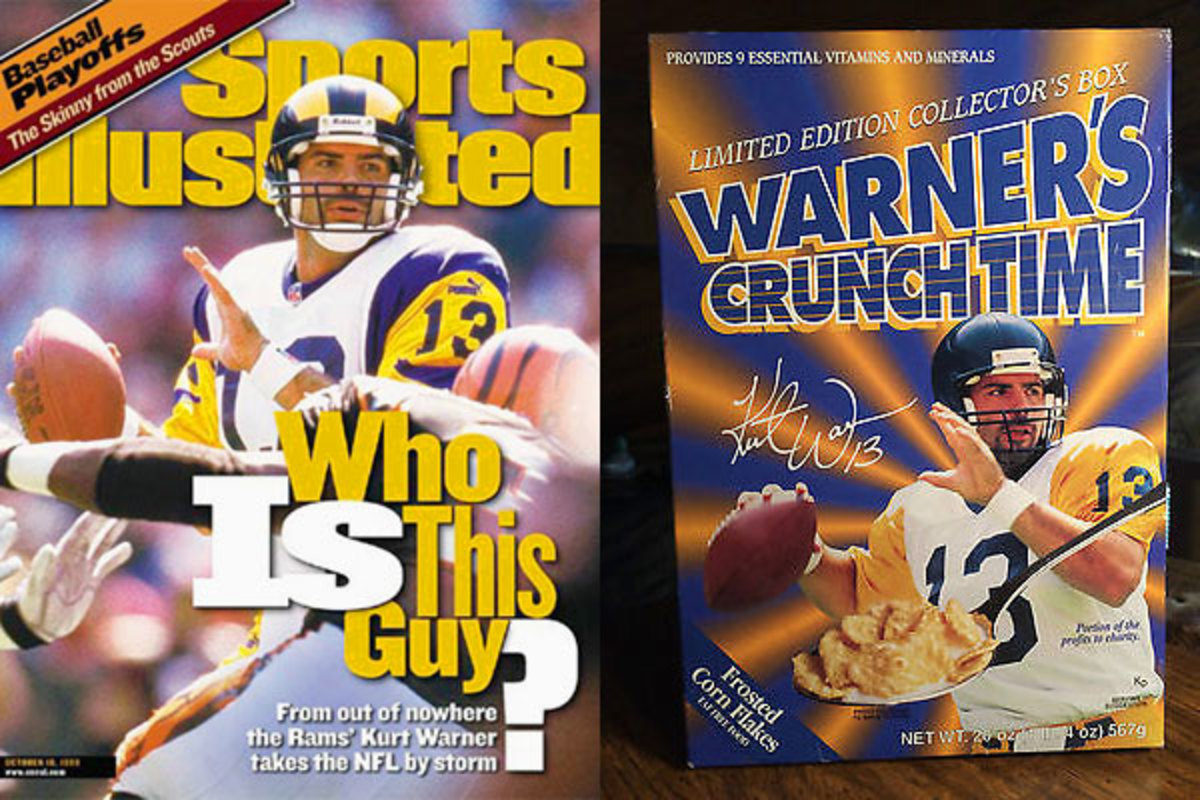

“Oh, sure,” he laughed. “There are certain iconic things that correlate with a dream. You want to be on a Wheaties box. You want to be on the cover of Sports Illustrated. You want to be able to say after the Super Bowl, I’m going to Disneyland.”

This was a man who survived by bagging groceries after being cut by Green Bay. I asked if in that former life he ever found himself in a humbling moment, staring at a cereal box, somewhere lost between the aisles?

“I can only imagine,” he said, “there were plenty of times when I was stocking the cereal aisle and putting up a Wheaties box with somebody else’s picture on it and thinking, I want that to be me.”

He played three seasons in the Arena league, threw for a gaudy 183 touchdowns, was named first team All-Arena in 1996 and ’97, and led the Barnstormers to Arena Bowl in those seasons as well. He always kept his eyes on the NFL. Finally he got a call from Chicago. The first time the Bears scheduled a tryout he was getting married. The second time it was his honeymoon. They were determined to give him a shot, so they scheduled a third. Just as he was about to come home from Jamaica he was bit by something. His elbow swelled to the size of a grapefruit. He was in no shape to throw. He called them to reschedule but never heard from them again.

“Maybe it isn’t in the cards,” he recalled thinking. “Maybe I’m not supposed to play, even though you feel without a doubt, if you get the chance, you can.”

For two years Al Luganbill, the head coach of the Amsterdam Admirals of NFL Europe, had tried to get Kurt to be his starter. But it wasn’t the NFL and Warner had a good thing going with the Barnstormers. He was reluctant to leave the country before getting one more shot at his dream. Al called around the league, but no one wanted to take a shot on a 27-year-old who’d never played a down in the NFL. The next year he tried again. Thirteen teams. Twelve said no. One said yes. The Rams.

Al convinced them to give Kurt a look but it didn’t go well. He’d broken the thumb on his throwing hand the year before and it wasn’t fully healed.

“I have probably the worst tryout of my life,” Kurt said. “Missing guys I don’t normally miss. I couldn’t control the football the way I wanted to.”

He tried to convince the Rams scout watching him that he was better than that.

“Hey, that really wasn’t me. I had this injury. If you give me another tryout, I promise I will be much better. I’m so much better than that quarterback.”

“Oh, no. You were great. We saw everything we needed to see,” said the scout, giving Warner what he thought was a line. “If it was up to me, I’d sign you right now.”

Crushed, Warner left and called his wife.

“I blew it,” he told her.

A couple days later, the Rams called and offered him a contract. He still firmly believes it was a courtesy to Al, whose NFL Europe team would have had the rights to Warner. “You want him to come play for you… We need a camp arm anyway… So sure…”

No matter how inspired I felt by Kurt Warner, I knew I’d never be an exception to football’s Darwinist rules. And yet, I had come to understand the sideways glances that all AFL players must get when they tell people they’re professional football players.

By 1998, he was back in camp with an NFL team. Warner spent his first year in St. Louis as the third-stringer, appearing in one game and completing 4 of 11 passes for 39 yards. He was otherwise relegated to the scout team, where he took pride carving up the Rams’ defense at practice.

“When I got back on the big field again, everything seemed to slow down. I had time to wait on the big field, to see things and gather myself,” he said.

His second year, in 1999, he was number two on the depth chart behind Trent Green, who was brought in on a big free-agent contract and immediately named the starter. Just a few months later, in their last preseason game, Green suffered a gruesome ACL injury and his season was over. That was how Kurt Warner, at 28 years old, found himself as the starting quarterback of the St. Louis Rams.

“If this doesn’t work for me,” he thought, “then I’m done.”

His first game against the Ravens he threw three touchdowns. Afterwards he was named the league’s offensive player of the week.

“I get a call telling me that I’m the NFL player of the week, or something, after my very first start,” he said. “I turned to my wife, sitting next to me, and I said, ‘You know what, if I never play another down in the NFL, I did it.’ ”

But he threw three touchdowns the next week as well. Three more the next. Then five. By Week 6 the Rams were 5-0 and Sports Illustrated had put him on the cover, with a headline that asked, “Who Is This Guy?” A month later Warner’s Crunch Time Cereal was on the same grocery shelves he once stocked himself.[3]

Warner led the league with a 65.1 completion percentage, an NFL-best 41 touchdown passes and an unmatched 109.2 QB rating. The Rams went 13-3 and won the Super Bowl. Kurt became just the sixth player in NFL history to be named league and Super Bowl MVP in the same season—and the only one to do it in his first year as a starter.

After such a bloody knuckled climb, I asked him to describe what it was like at the top. It was difficult for him to put into words. After a searching pause he said, “It was the culmination of everything.”

Kurt Warner’s life had all the makings of a Disney movie. So I had to ask: What was it like shooting that commercial?

He laughed at the memory.

“It took like a million takes to do it. You’d always wanted to be that guy saying it, and then here you are and you just want to go celebrate with everybody, and they’re like, ‘Oh, we didn’t get it, you’ve gotta do it again. You gotta do it again!’ And I’m like, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m Going to Disney World!’ ”

I asked him if it’s still possible to follow that route up the mountain. Whether men who said to themselves, If Kurt can do it, so can I, were justified in their belief. He sounded doubtful.

“As much as you can say Kurt Warner went and made it, it’s been 15-plus years since I did that. There’s been a couple other guys, there’s always a few exceptions to the rule, but it’s been a long time.”

Wouldn’t you say that everyone has to believe that they’re the exception to the rule?

“You have to believe that. It’s already built in as an athlete that you’re invincible anyways, and this is just an extension of that.”

He recalled a speech at a Shrine game during his senior year of high school. Part of the motivational speech that day was to tell the players that one, maybe two of them, would make it to the NFL. For most everyone there it was demotivational. A friend of Kurt found his eyes and gave him a look of sympathy.

“What?” Kurt remembers thinking, “I’m gonna be one of those guys.”

He seemed to say both things. It’s damn near impossible, but if you’re called you have to try—and if you try, you have to lay it all on the line. In that spirit of exceptionalism, I asked him for advice on how I could make it in my quest to prove myself as a football player.

“The one piece of advice, and really the only piece of advice: just stay ready. Did you prove in whatever period of time that you belonged? You’re probably only gonna get one shot.”

* * *

Another Pretender in a Strange Town

Los Angeles is different from any city on the planet. You can wash up here with only a vague notion of wanting to be a star, and somehow luck into it all happening for you. It doesn’t really matter what sort of star either, most people pick their talent later. The magic of the town is make-believe. L.A. is like living in a costume party where everyone treats their disguises as reality. Here, and nowhere else, you can spin a career out of thin air and actually be taken seriously.

“Sure. You’re the next Elon Musk, Meryl Streep, Kanye West, Gigi Hadid; whoever you want,” you reassure an important someone. “Of course you are! Have another drink. We’re all famous here. Why, the president of Space is running around here somewhere!”

No one wants to ruin anyone else’s trip by pointing to the truth. Maybe from the fear that if you did, they might return the favor. The very bedrock of Los Angeles is fantasy. We make ample space for even the most deluded of dreamers, but only long enough to escape to the safety of our cars, lock the doors and drive away. Thank god I’m not like that, we say, shuddering at the poor fool. It’s a funny town.

I say all that to say this: when I told people that I was going to be a professional football player, most met it with a shrug. Some accepted it as Californians might accept another sunny day. Some laughed at the audacity of what they perceived to be an outright lie—somehow being a pro football player seemed less realistic than becoming a model/DJ with an interesting hat—but most Angelenos would muster at least some encouragement.

“Cool!” they’d say, or, “Football, hmm. Have you seen Concussion? Will Smith does an amazing Nigerian accent.”

Those that thought of themselves as concerned intellectuals would want to engage on the social issues of the game. But the cool kids, the bobo glitterati of the Hollywood Hills, Venice and Silver Lake, were sphinxes of indifference.

The very bedrock of Los Angeles is fantasy. We make ample space for even the most deluded of dreamers ... but back in my old haunts in New York, my plans were met with a more robust skepticism. My friends just laughed at me.

At a party in the Hills I told a knockoff Joni Mitchell what I proposed to do. As I explained my quest to play Arena football and become a member of the LA KISS, a glassy look set behind her eyes and remained until the subject moved back to her charity work, the cycles of the moon and what camp to stay with at Burning Man.

A friend of hers in a serape and a trimmed beard, kind of a farm-to-table Clint Eastwood, approached and joined the conversation.

“This is Neal,” she said, introducing me. “He’s an actor, but he’s writing something. Journalism… I don’t know… Like Sean Penn.”

“Sean Penn,” Clint mused. Then he stroked his beard and eyed me. “Interesting. He’s pretty gonzo. Like Thompson. Bukowski. Hmm, yeah. Hemingway. Real, man. Realer than real.”

I sensed that he had come to the end of the writers he knew.

“Yes,” said a bored Joni. “He’s like Sean Penn without the movie career.”

Sean Penn. I should’ve seen it coming. The actor and experiential journalist had written a 10,000-word screed about his meeting with El Chapo in the hills of Sinaloa. It read like a middle-aged man three whiskies deep, trying to impress a dinner party in Malibu. Charlie Rose tried to hold him to account, but the wily Penn defended himself. All he had to do, he told Rose, was simply sit down with the cartel boss, look him in the eye, human to human, ask two questions about Pablo Escobar and his mother, and he’d get to the bottom of the Drug War. Such was the power of Penn’s humanity.

The school of New Journalism that Penn claimed to represent was hallowed ground. Tom Wolfe, Hunter Thompson, Gay Talese, Joan Didion, Truman Capote, Pete Hamill, Norman Mailer, George Plimpton … it was a heady club. But where they had all broken new ground, Penn succeeded only in breaking wind and attention spans. Much as I’d love to add Jeff Spicoli to the canon, I felt the need to distance myself from him.

“Not really,” I said to Joni and Clint. “More like George Plimpton.” Neither knew whom I was talking about. I clued them in: “He was one of the failed psychiatrists in Goodwill Hunting.”

They nodded with silent enthusiasm.

Finally, Joni broke in.

“It’s almost a new moon,” she said, turning hopefully to Clint.

A little while after that I was on a date with a lovely Irish lass. My friend who set us up had pitched me to her as a writer rather than an actor, no doubt to make me seem smart. As we searched for what to talk about over our drink, she asked what I wrote. I told her. She even seemed receptive-esque, but it may have been the booze. Neither of us was really feeling it. Afterwards, as our polite texts fizzled out, she parted by saying, “Good luck with the Anaheim Soccer Project.”

Back in my old haunts in New York, my plans were met with a more robust skepticism. My friends just laughed at me. I was at dinner with two of them after a play. My friend Tom asked me, “Bledsoe, what have you been up to?”

When I told him he just stared at me in a shocked silence, unsure if I was kidding. He turned to my friend Quincy for an explanation. Quincy nodded, like a doctor concurring on a terminal disease, That’s right, he’s got the football and it’s not looking good! Then both of them broke out in great peals of laughter. Diners at adjacent tables turned and stared, some mid-bite. For a moment it seemed as if the whole restaurant might join in.

A filmmaker friend of mine heard only Sports Illustrated and assumed I was involved with the swimsuit edition in some way. She sent me relentless inquiries on the development of my “bikini bod.” I kept insisting that this was a serious football story, no bathing suits to be found. She refused to believe me. When I finally stopped responding, she sent a doomsday supply of gummy bears in a blatant attempt to sabotage me.

Upstate, my film father was even more blunt. It was his last night in town and he was drunk. The cast was drunk too, though not quite as much. Our block-and-a-half walk to the hotel took 15 minutes and three cigarettes to complete. His topics of conversation swung wildly, like his gait, across the sidewalks and into the street. We covered it all: death’s door, space alien probes, the meaning of life, ear candling, before we finally turned to football.

“Listen,” he told me, suddenly stopping “you gotta be careful with this whole football thing. You can’t take it as a joke.”

I told him it was no joke. He pursed his lips and exhaled sharply through his nostrils. He must have felt he was misunderstood. He focused his eyes into a squint and traced the outline of my skull with his lit camel.

“You’re like this, this…”

It seemed as if a great truth was about to pour forth from this drunken oracle. Finally the perfect words came to him.

“…delicate moron.”

His words hung there in the night like the cold sting of a slap. Then he roared with laughter. He destroyed himself with it, buckled at the knees and fell into a fit of coughs. I stood there, determined to escort him back to the hotel no matter what. Although, I should admit, I did the quick math on how long it might take him to die of exposure. Eventually he composed himself, lit another cigarette, and we made the final 50 feet home.

What was clear to me was this: no one was exactly sure what I had proposed to do. Everyone knew it had some vague thing to do with football. Beyond that, it was lost on them—a quixotic bit of foolery. I admit it sounded absurd. I tried to qualify this by saying that it was Arena football. But no one really knew or cared what the AFL was. Most people considered my new “career” in football as nothing more than a joke. A joke in a league that people confused with indoor soccer.

I long ago had abandoned any hope of ever landing on a Wheaties box or the cover of Sports Illustrated, swimsuit or otherwise. And no matter how inspired I felt by Kurt Warner’s transformation from grocery clerk to maestro of The Greatest Show on Turf, I knew I’d never be an exception to football’s Darwinist rules. And yet, I had come to understand the sideways glances that all AFL players must get when they tell people they’re professional football players. This was a title I had yet to attain myself, but I was now doubly determined to make the team—not only to spite my doubters, but also to convince them of the beauty of this game and the nobility of its players.

On the morning of my tryout with the LA KISS, I stood alongside scores of other hopefuls. We were outsiders looking in—some on the way up, others on the way down—not one of us thinking this was a joke. At that moment, anything was possible. The dream was still alive. We were just 20 miles from Disneyland, but for many of us that’s as close as we’d ever get.

[1] Disney approached both John Elway and Phil Simms before the game. They were both offered $75,000 for a commitment that the winning quarterback would say the phrase. As the winner, Simms was also given airfare and tickets for his family to and from the park, where they threw him a parade. Something that New York mayor Ed Koch did not do for the Giants that year.

[2] With two notable exceptions. Disney called a timeout on the NFL the year after Janet Jackson’s wardrobe malfunction. As well as this past Super Bowl, when Peyton Manning elected to drink Budweiser and Von Miller was heroically quoted as saying, “F--- Disney World, I’m hitting the strip joint. All of them.”

[3] Kurt Warner never got his Wheaties box. Crunch Time was a limited edition cereal. Later, he would also have a video named after him, Kurt Warner’s Arena Football Unleashed. It was also a one-year thing. In 2009 Madden put him on the cover. These days that’s a bigger deal than cold cereal. Except there’s no curse that comes from a Wheaties box.

• Question? Comment? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com