Inside the Film Room With... Jarran Reed

My phone buzzes at 10:35 on a spring morning in Tuscaloosa. It’s Jarran Reed. He’s 25 minutes early. “I’m up here at the office,” his text says. That would be the main football office on the second floor of the Mal M. Moore Athletic Facility. The building is part of the immaculate brick laid sprawl that is Alabama’s athletic compound. It sits on Paul W. Bryant Drive, about a 15-minute walk from the center of campus (also immaculate) and 20 minutes from Tuscaloosa’s charming and, in spots, trendy downtown.

Reed, Alabama’s first-round projected nose tackle, and I are meeting to watch his film from last season’s games against Arkansas and Tennessee. We’ll be in the inside linebackers meeting room, where our camera crew is setting up. On the front wall is a large projector screen. On the back wall are floor-to-ceiling paintings of former ’backers C.J. Mosley and Nico Johnson. In between, five rows of theatre style seats.

As the crew finishes preparations, Reed strolls into the team rec room. Talking heads babble on three flatscreens. Nine leather recliners sit empty. There’s a nutrition bar in the back, behind air hockey and foosball tables. Also, two pop-a-shot stations, where Reed casually stops and starts firing very assertive bank shots.

Reed is 6-foot-3, 307 pounds and baby faced, sort of like a younger B.J. Raji. He played basketball in high school. Low post. After 10 or 12 clattering shots, our crew is ready. It’s time to start watching Reed play the sport that will soon make him rich.

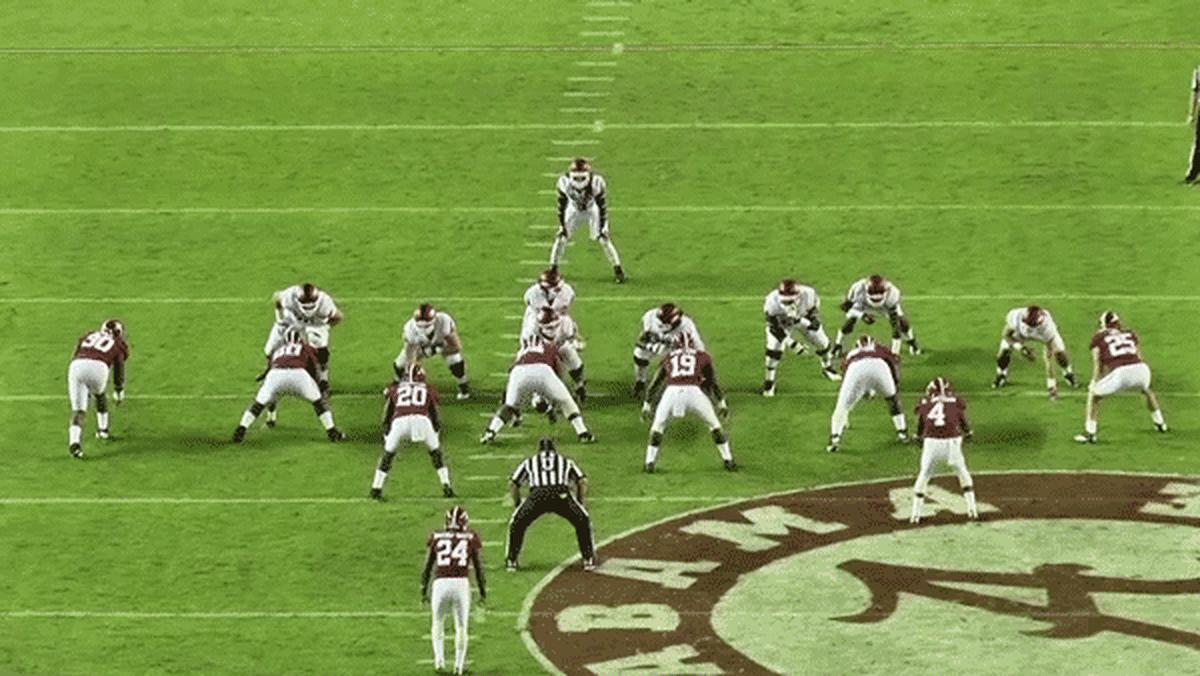

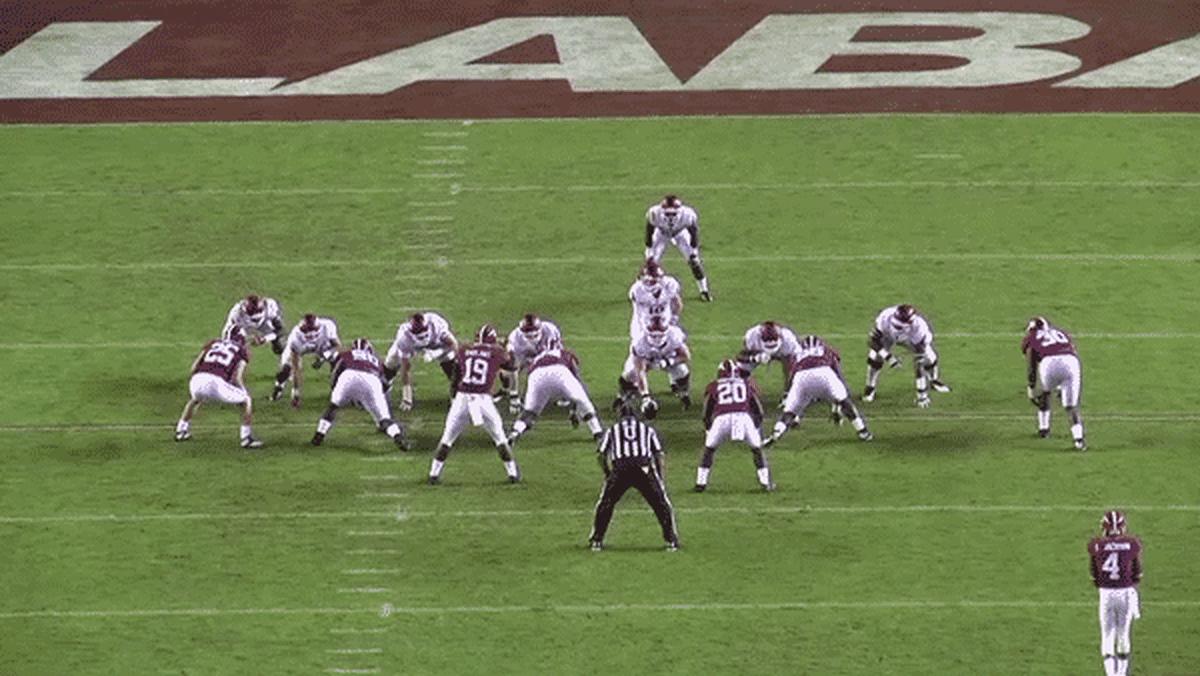

We sit in the first row, clicker in hand. Reed is an old-school strong man—a low-to-the-ground force who plays everywhere along a defensive front. His forte is two-gapping. We see this on the first Arkansas play.

“I’m kind of cheated over [in my alignment] because I’m about to run a stunt,” Reed says. “I’m supposed to just occupy the A-gaps. So when the guard comes down, I got my hands inside and I’m pressing off of him. I’ve got him back behind the line of scrimmage. Now, I’m looking for the running back because it’s a counter play. See (Arkansas left guard) Sebastian (Tretola) pulls on the inside? As soon as I get my hands inside, you know I’m controlling the point of play. I got him and the running back now coming downhill. I just released off the lineman and made the tackle.” It’s gap responsibility first, ball location second.

Next play.

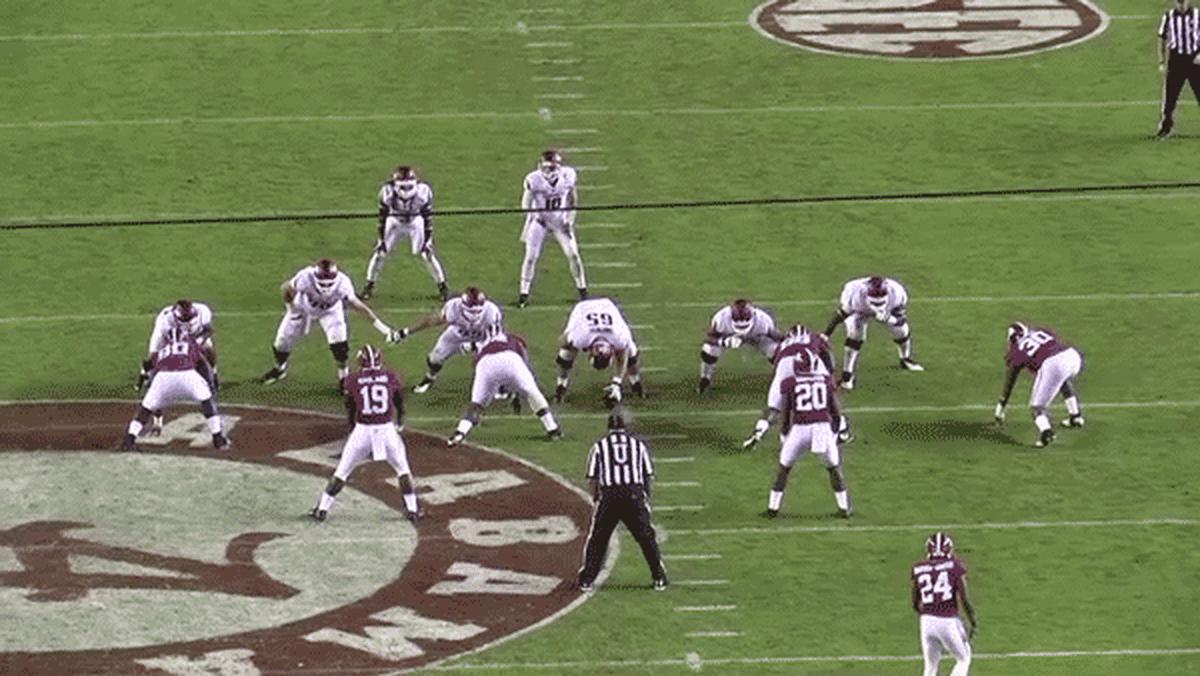

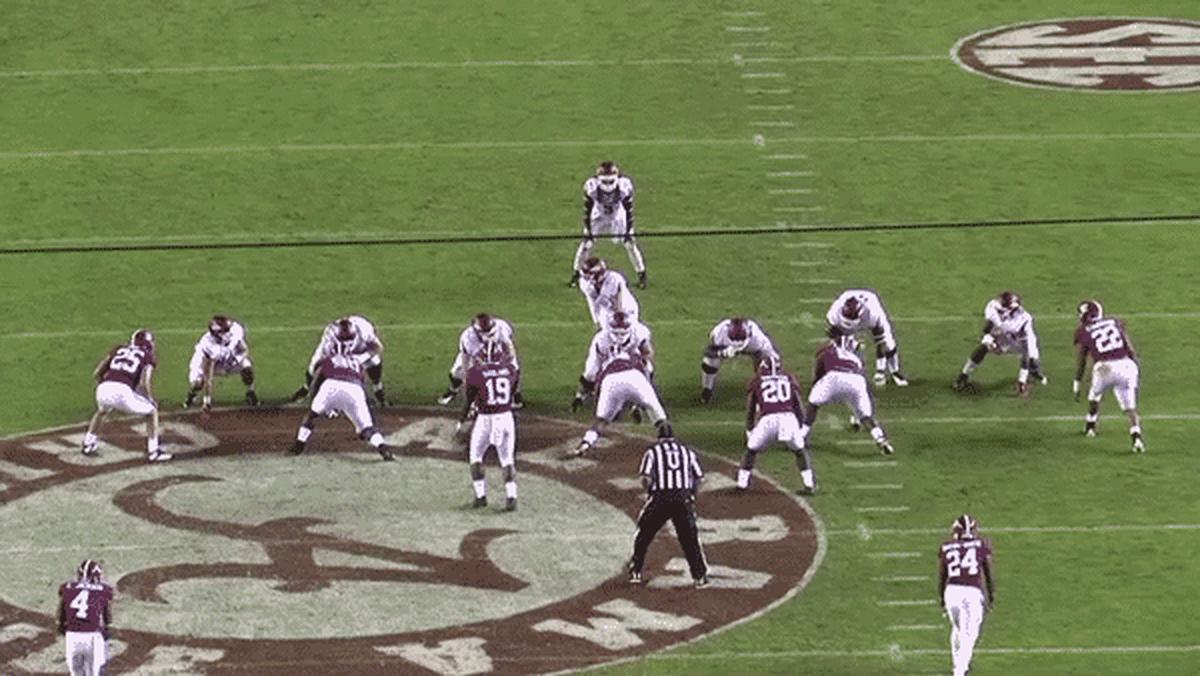

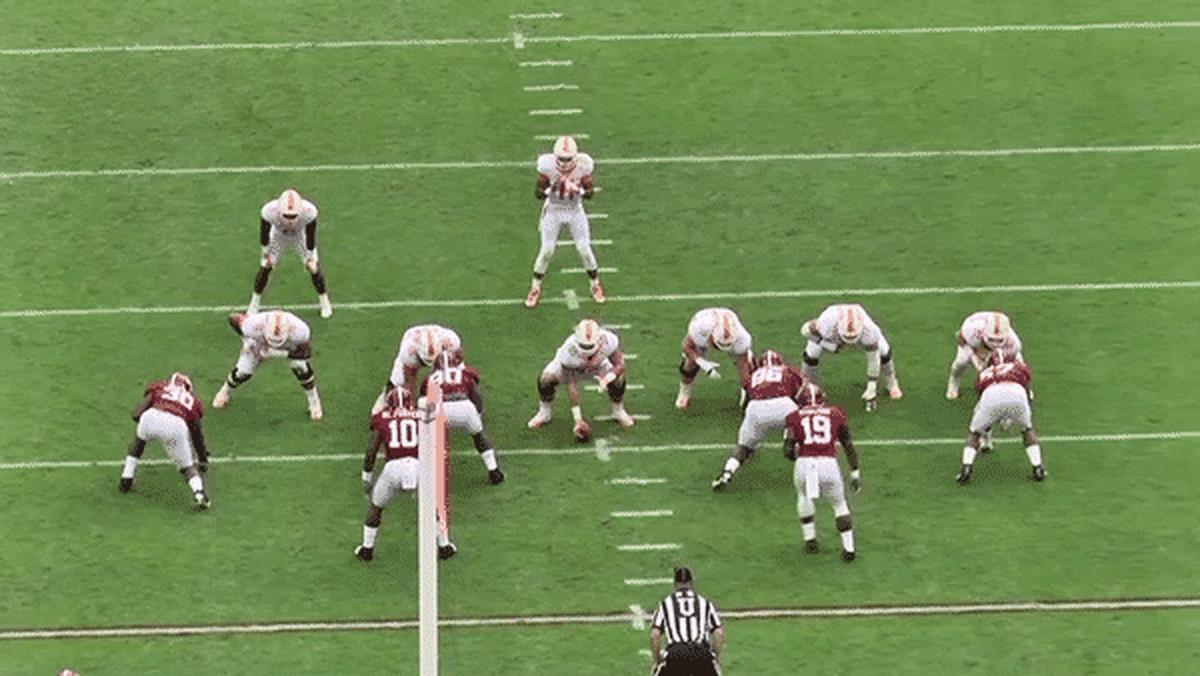

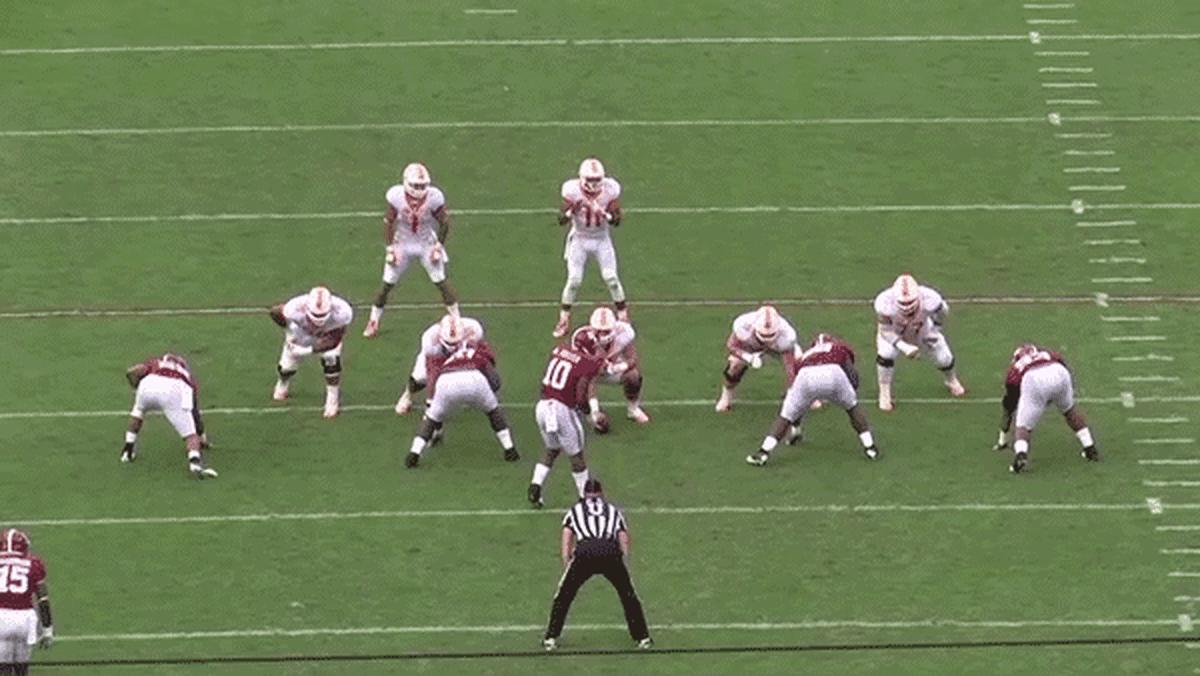

We as defensive linemen “are taught to read the formation,” Reed says. “Our main thing is tight ends and the depth of the running back and the quarterback. See like right here, we’ll look at the depth of the tight end back there. See the tight end, he’s stacked away from the tackle. This is [more of a] pass situation, but we know they’re a heavy run team from film. So, from that point on, we already know it’s a run because the quarterback is under center. We already know what he’s about to do.”

Early in the second half, Reed makes a dominant stop from defensive end.

“My primary gap was the inside gap. I wanted this play from the beginning with the tight end. He didn’t even have a chance, if you ask me.”

“He got his hands on me and I throw him inside. See, I’m inside with him. My eyes are inside from the jump. That’s my gap. The running back sees that. Running backs are taught to read people, read defensive linemen’s eyes. He has nowhere to go so now we’re just playing cat and mouse.”

I ask Reed if there is a tight end in college football who has a chance at blocking him.

“In college football, no.”

How about the NFL?

He ponders and then says, “No.”

You sure?

“We go against big guys. I don’t think my coach would be satisfied if we got blocked by a tight end.”

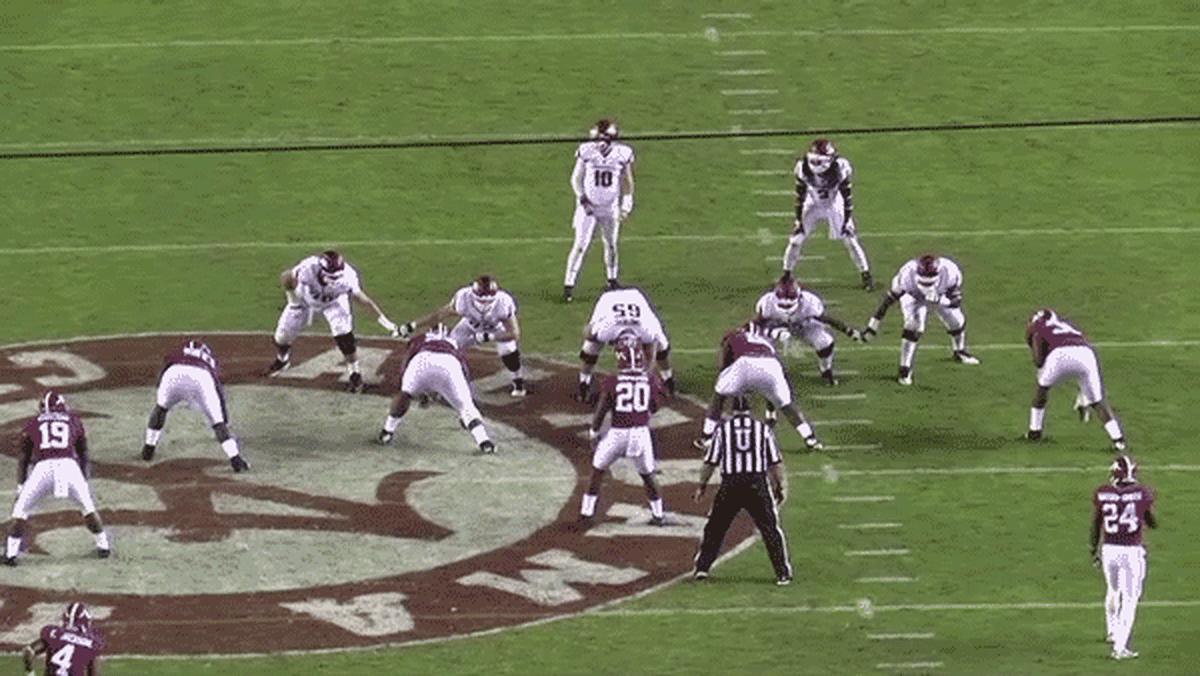

Next up, a pass play. We see Reed get penetration on a stunt with fellow defensive clogger Daron Payne. Payne was the “penetrator,” attacking the B-gap to occupy the right tackle and guard, creating a lane for Reed to loop around into. Arkansas had a protection slide called to that side—a tactic that normally negates a stunt. But Reed still got penetration.

“We knew they were going to do that slide just from watching film. You see the running back is on the opposite side waiting so they’re going to slide away from him. Once the running back [took a step up], he came to our pass rush. We took a different approach to this stunt. We’re going to get more leverage upfield. Daron comes in tighter. Even though with them sliding, the guard and tackle will stay on the man coming inside that is trying to penetrate. When I come on, there’s going to be a blocker waiting. I just had to work a counter move. Then it just became a cluster-bust in the middle, but we were still pressuring the quarterback. The quarterback didn’t feel comfortable, as you see.” It was a decent play, but as Reed later notes, it could have been cleaner.

The next play is a false start. I chose it because Reed took the opportunity to give right tackle Dan Skipper a shot. “You’ve got to, man! You’ve got to! The whistle wasn’t blown yet. And it’s football!”

But let’s be honest: this was about a beat-and-a-half too late to be a knee-jerk reaction.

“There’s a little pause,” Reed concedes through a wide grin. And then: “I mean, they could do it to us. Take a little shot back. My bad, ref. My bad.”

Skipper clearly took umbrage. You remember what he said to you right here?

“I really don’t because once I did see him, I kind-of zoned out. I probably was looking at him but I won’t be hearing what he was saying. That’s pretty funny though.”

On the next play, Reed gets too tall out of his stance. It was an overcompensation for battling the 6-foot-10 Skipper. “I’m trying to get my hands up under him,” Reed says. “There’s no excuse for it. I definitely could have stayed down right here.”

After this, Arkansas runs an inside zone. That means a double-team on Reed, with one of the blockers trying to work off of the double-team and up to the linebacker. Reed prevents this, allowing Reggie Ragland to make a clean stop.

“The guard’s job is to push me out the gap so this right tackle can work me inside, possibly so they can hit inside with the run, but that’s not going to happen,” Reed says. “I just have him jacked up. My hands are inside of him. He’s mine for the play. I’m controlling him. He has nothing to do. And obviously, he’s a little bit mad.”

Asked if he’s a trash talker, Reed says, “I say a little something here and there. People, they know, I’m there.”

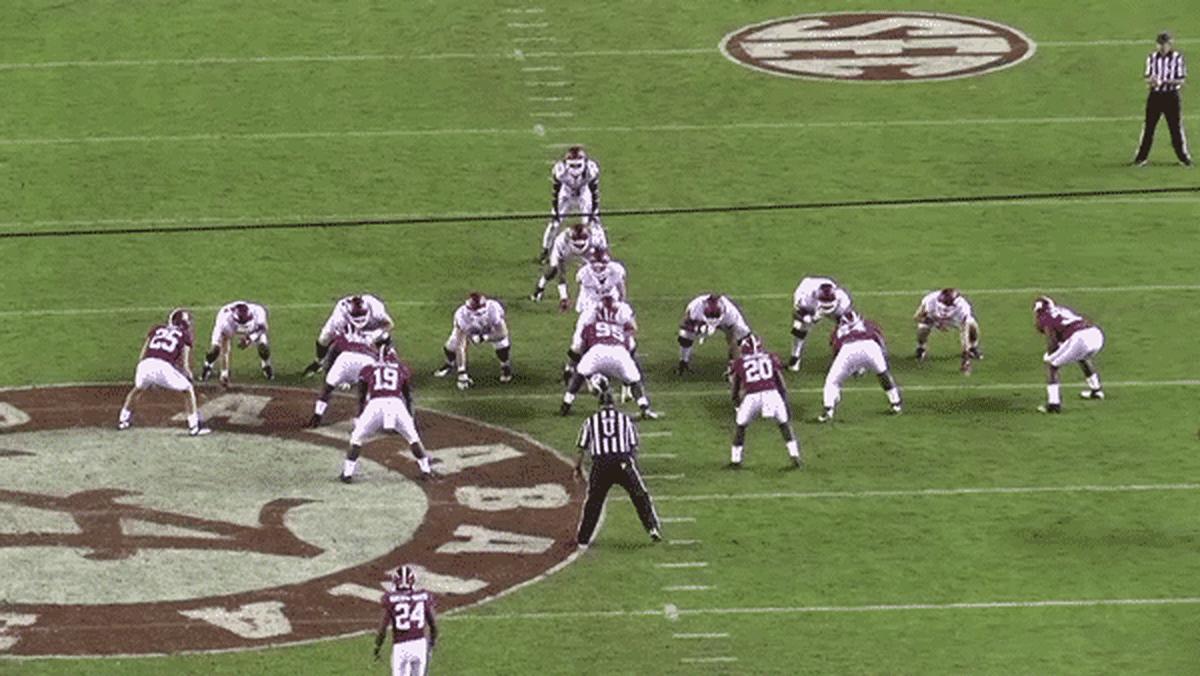

The last play we watch from the Arkansas game is a run stuff against a shotgun draw. The D-line kept the linebackers clean.

“We know nine times out of 10, if we’re in a three-man front and I’m at nose, people are going to try to double-team. So, I’m just striking, winning from the jump. I’ve got him going backwards, going forward, my hands are inside. I’ve got the guard on me. I’m doing a good job of keeping the linebackers free. But, as I’m in the double team, I shouldn’t have spun. I don’t know why I did that. But I felt like I’ve got a real knack for the ball. I’ve got a real instinct so I can tell where he’s going.”

By spinning, Reed happened to guess right on the play. But it was wrong to be guessing at all. What does position coach Bo Davis say to him here?

“He’ll tell me stay inside, which I know. He wouldn’t even have to tell me.”

* * *

On to the Tennessee game. A few doors down the hall, in Alabama’s defensive meeting rooms (more of an auditorium, really), on the wall is a game-by-game chart of each defensive player’s “production points.” Production points come from statistical output plays plus subjective things like QB hurries and effort. Atop the list is Ragland, the All-American. One spot behind him is Reed. In the Tennessee game Reed scored 13 production points, his second most of the season.

“This was by far one of the most fun games we’ve played,” Reed says. “Tennessee, I don’t think they’re a team that gets a lot of recognition around the SEC, but they’re actually a good team. We had to kick it into gear as the game went on. We pulled this one out.”

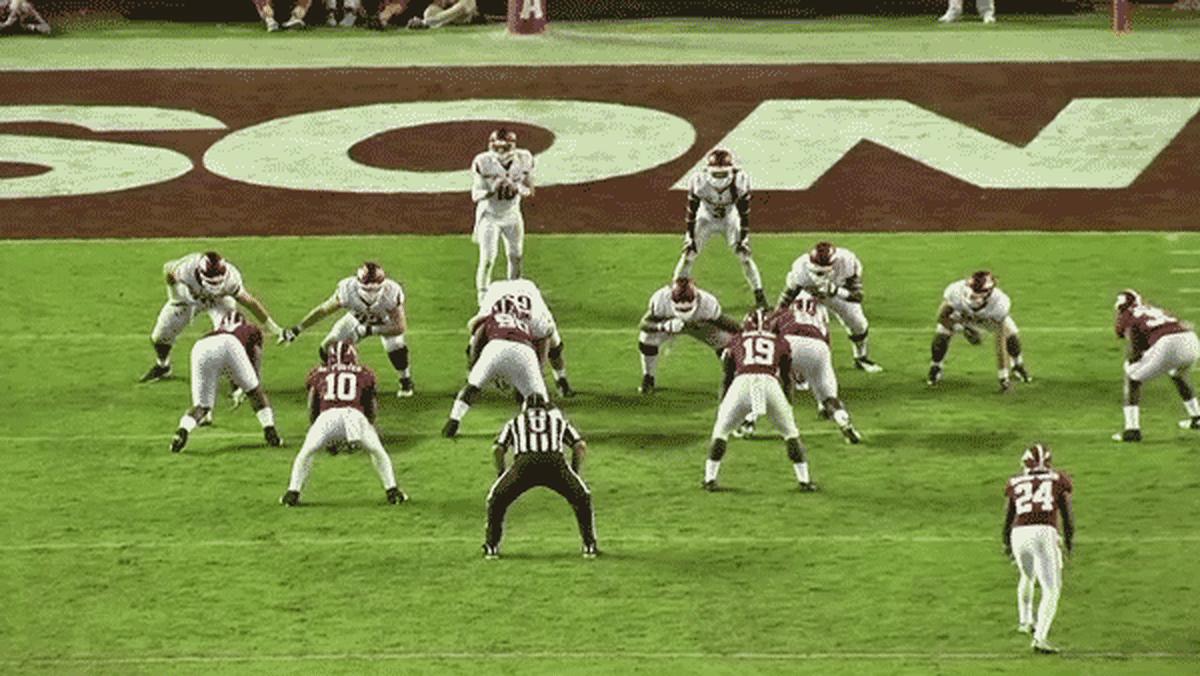

Tennessee gets into a pass rushing situation. Reed does not play in several of Alabama’s nickel and dime sub-packages. In this area he has more to prove. You see flashes of potential, but not on this particular play. Part of the problem was the constrictions that a mobile quarterback placed on the pass-rushers.

“Yes I could have rushed more [on this play], but I was trying to split those gaps,” Reed says, explaining that Bama’s four rushers had to stay balanced in their lanes here. “Especially in our defense, it’ll mess things up if you give a lane for the quarterback to run.”

Reed stayed in his lane, but he generated zero heat on the passer. So how would this play be graded?

“It would be a positive play for the defensive line but a negative for me. I needed more rush on this play. Our coach would say ‘Stop watching the quarterback.’” But as Reed and I discuss, to fans—and maybe even NFL scouts—who aren’t privy to the defensive call and are unaware of the pass rushers’ specific lane responsibilities, Reed’s output here would look baffling. “Yeah, it’d be like, What’s this guy doing? Why is he standing around?” Reed says.

After a few more trench battles, we come upon a play on which Reed has to move laterally in order to defend a “G sweep,” where the center pull-blocks to the perimeter. Reed did a nice job, despite playing too tall initially. He allowed Ragland to explode into the ballcarrier.

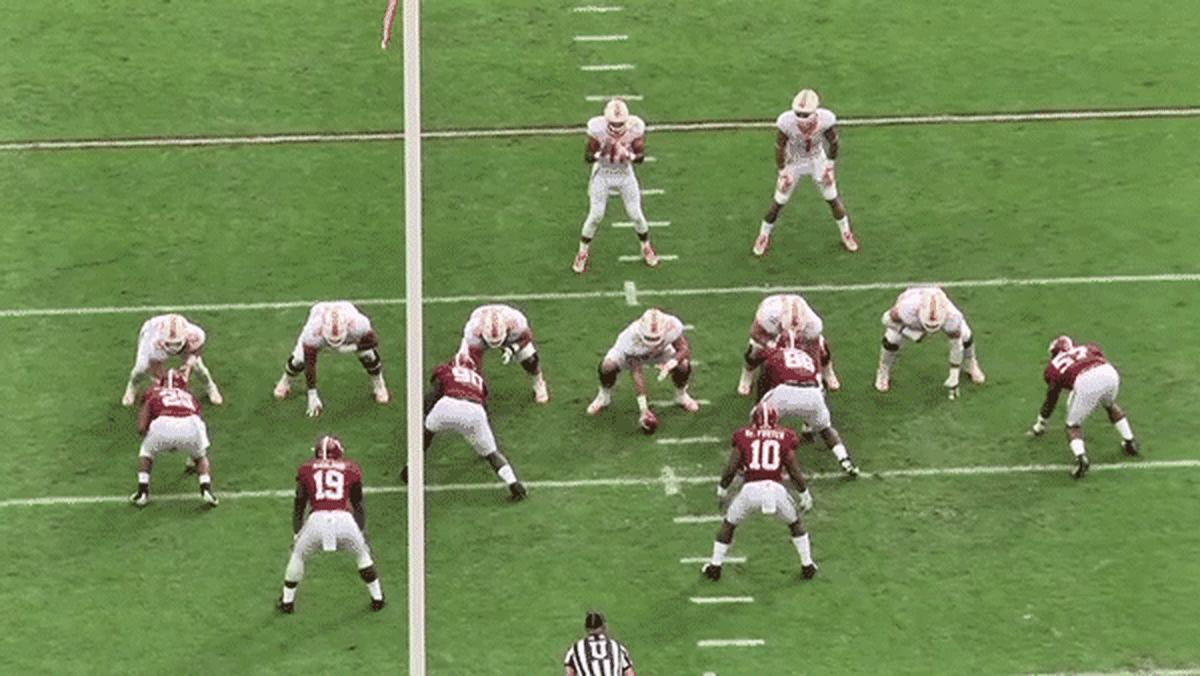

“This is one of the plays where I was like Ooh on the field. We knew what they were about to do. The tackles are up and are ready to kick back. It’s obvious,” Reed says.

What made it obvious was how several offensive linemen were high in their stances. “They’re all kind of light on their fingertips, too.”

A few plays later, Tennessee runs another sweep, only with the center and backside tackle also pulling. It’s an unusual tactic, and Reed had what he calls a “discombobulated play.” His upper-body went one way, his lower-body the other. “I had a talk with my coach about this one in the film room,” he says.

Reed sat out the next few series; it was just the nature of Alabama’s D-line rotation at that point in the game. This inspires me to ask: In the NFL, if you’re facing a team that runs 70 plays a contest, some of them up-tempo and some of them huddled, how many of the 70 do you think you can endure and play at a high level?

“I’ll give it all I’ve got and go out for all 70 plays,” Reed says, not surprisingly.

But for 16 weeks? Not many interior defensive linemen can do that.

“It really just depends on how you’re taking care of your body, especially after a long game. But I don’t think there’s any particular player that can do 70 plays a game, 16 weeks. Just being realistic. You’re obviously going to need somebody to come in. But if you’ve got to, it’s what you’ve got to do. Some teams are not fortunate enough to have eight or nine players who can come in and play like we did.” One thing Reed learned at Alabama about taking care of his body is to stretch at least 2-3 times a day.”

Eventually we come upon a near-sack for Reed when he impacted the quarterback’s release, causing a flutter ball that linebacker Reuben Foster failed to haul in.

This probably could have been an interception.

“It should have been.” Reed says. “This is the one I was waiting for the whole night. I knew they were going to give me a one-on-one type block with this rocket sweep they were doing. [The right guard] was getting up to me the whole game. I was waiting for the right time to run it. Here, he’s horizontal. He’s giving me ground so I know if I get my post and get my hips around, as soon as he sets his feet, I come with the pull-slide move.”

Foster and Reed are brothers in the Omega Psi Phi fraternity. “I would tell Reuben here, if you can’t catch those, man.” He shakes his head. “It’s time for us to get off the field. He had it right in his hands actually! It would have helped me out. I would have caused a turnover and he would have the turnover!”

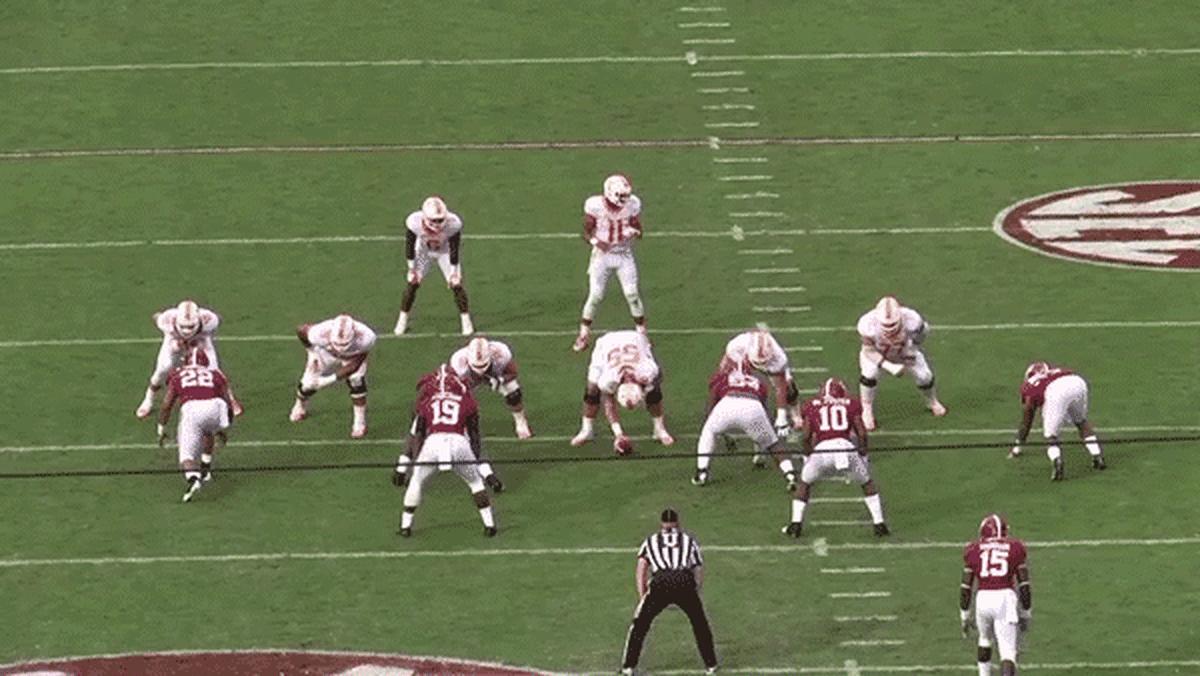

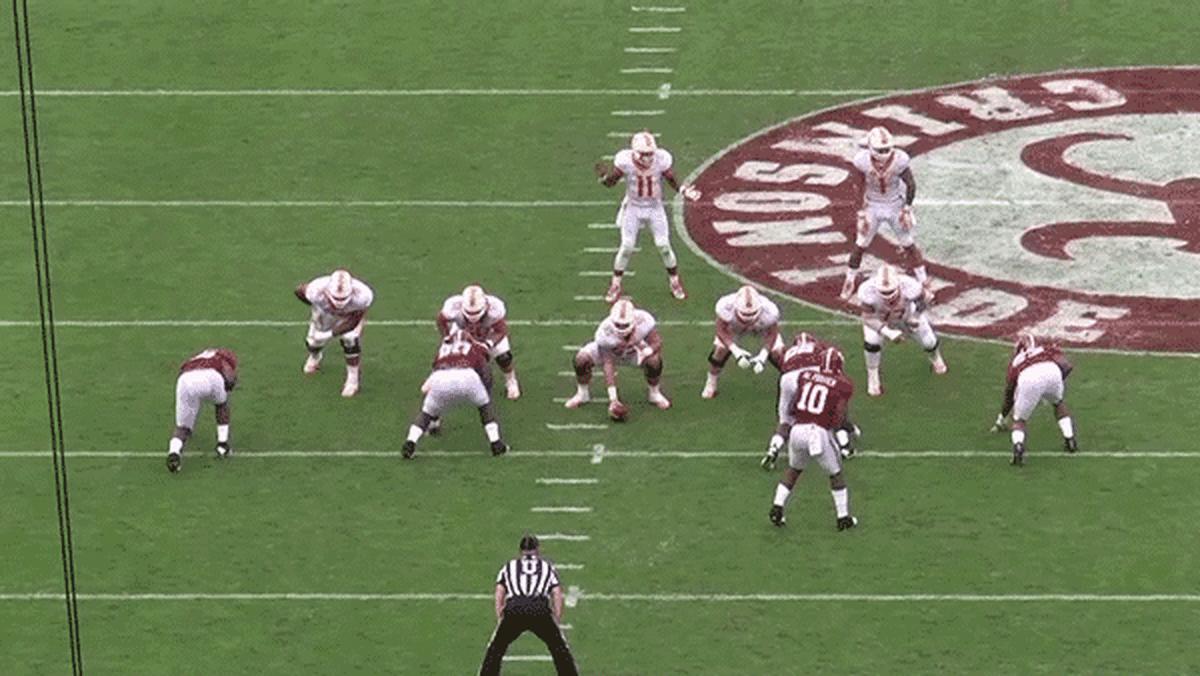

We come upon a play that Reed recognizes right away. “Oh yeah. I know this play. This is all about being a man.” We see the tight end aligned in a wing position outside of the left tackle. That’s an indication that Tennessee is about to bring action back to the outside.

“You can’t see it but he’s trying to get my facemask just to make me madder,” Reed says, highlighting guard Jack Jones. “So by the time he’s trying to come down, I’m fighting against the pressure, holding a point. I release off, the running back is right there. A perfect time to wait on him. You’ve got to be a man. A collision ensues.

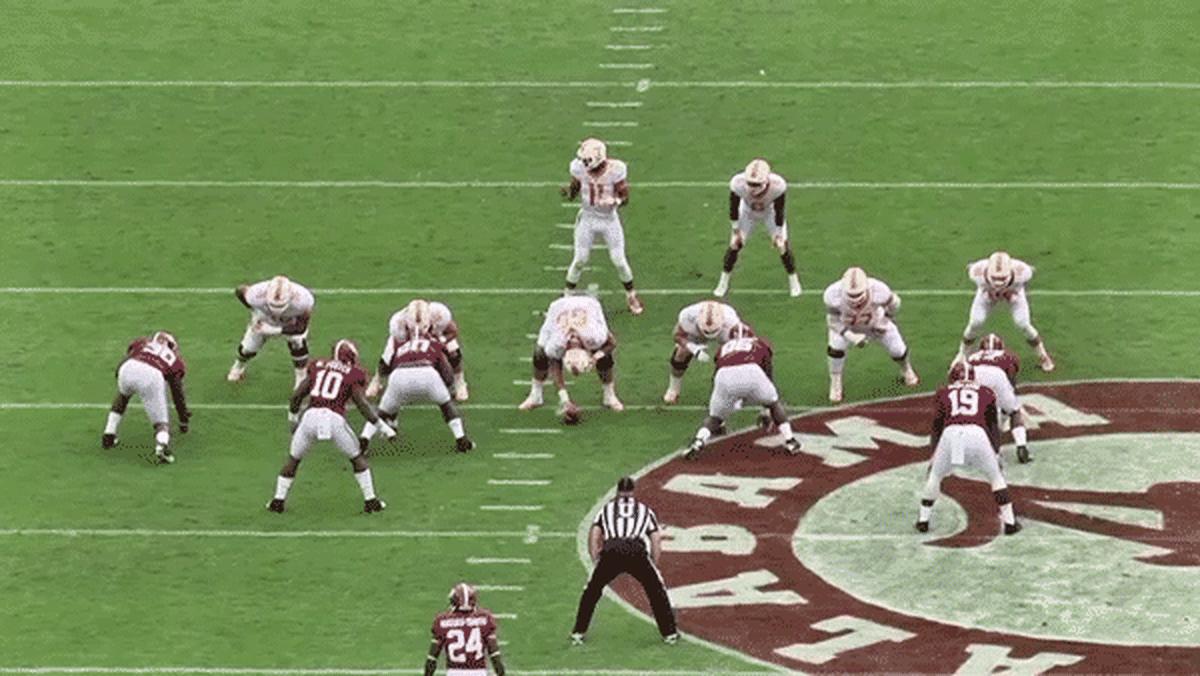

As we near the end of the game, we see a quarterback draw.

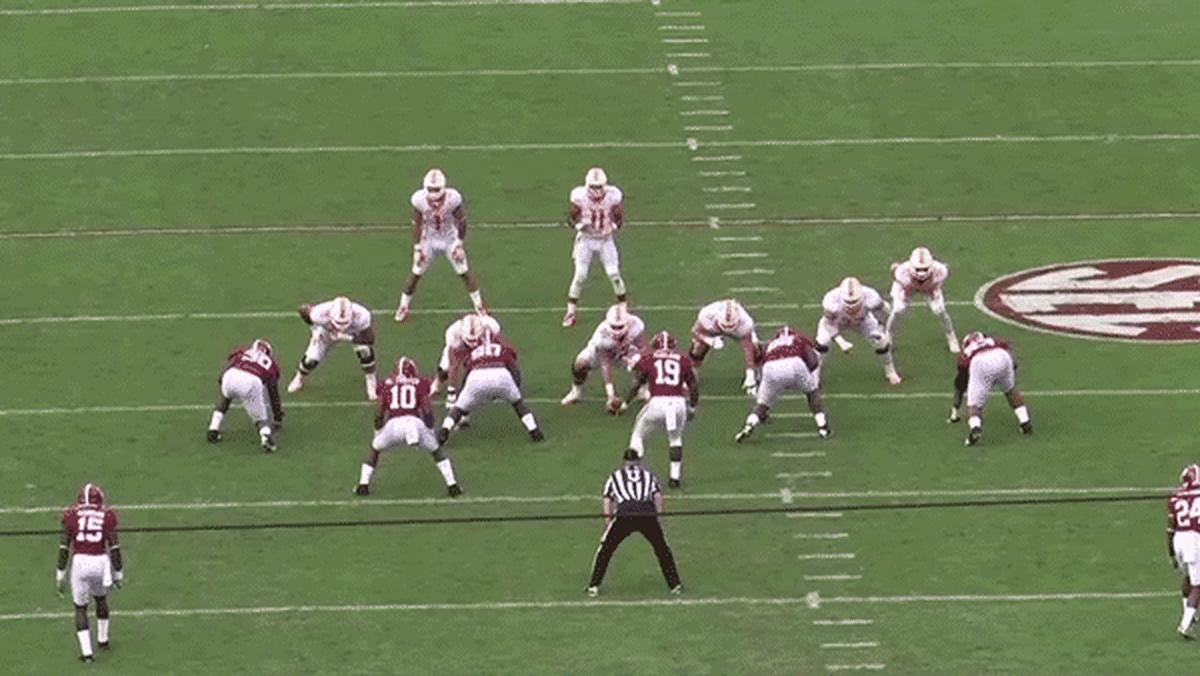

“This point in time, we’re rolling now as a defense,” Reed says. “Everybody’s playing a little bit faster.” A QB draw is an excellent tactic to slow down defenders who have pinned-back ears. “(The blocker here), was too much of a soft-setter [on this play], so I just throw him in the gap. It was too good to be true.” Something was up. “I knew then I had to get back inside to the A-gap.”

The next play also seems too good to be true, but it’s not. The quarterback, flushed out of the pocket late in the down, had nowhere to run but right into Reed, who’d executed what had turned out to be a fruitless stunt.

“I’m supposed to have outside contain and I’d been wanting it. You know, Dobbs kind of had us all stirred up the whole game… I definitely wanted to get a lick on him. My eyes got bright. My job is to keep outside contain. I can’t really run upfield because it would give him somewhere to go. So just contain him. He’s going to come to me as he did.”

Reed pulled a Tony Siragusa here. He let his full body weight land on Dobbs as he hit the ground.

“I had to give him a blessing. It was a clean hit. It wasn’t after the ball was thrown.” (Technically it was, but only by a hair. There was nothing dirty about the play.)

We rewind and watch a few more times.

“Right about NOW, I’m like, yeah, he’s coming. If [teammate D.J.] Pettway doesn’t get him, I’m about to get him. I was just like, Please come outside. So I kind of baited him. I just wait, wait. I let him run outside so I could actually bring him to the hit.” After six or seven viewings, the momentum of seeing the hit wears off, and Reed’s more sensible side can’t help but seep through. “I probably should have attacked faster than that. He probably wouldn’t have completed the pass,” Reed says. Sometimes free full-body shots on quarterbacks are too hard to pass up.

After we run out of film to watch, Reed and I chat. He talks about modeling his game after Ndamukong Suh and former Alabama great Marcell Dareus. “They’re nasty. They’re mean and that’s how the game is, especially playing as an interior defensive lineman.”

We talk about Reed’s upbringing. He and his bigger brother Dee (literally, bigger: 6-6, 340) were raised by their mother in the small town of Goldsboro, North Carolina. They grew up in modest means. I ask him what it feels like to have that sort of background and know that, a few months from now, he’ll be a millionaire. What goes through your mind when you wake up in the morning these days?

“It just makes me that much more responsible,” Reed says. “People are really counting on you now. You can’t mess up because just as quick as you got here, it can be taken away even faster. So to me, it’s not really about the money or how much I’m going to get. Now, you’ve got to produce.”